Journal of Educational Planning and Administration Volume XXXIII No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

S.No. AUTHOR TITLE 1. Rishi Singh State Formation and the Establishment of Non-Muslim Hegemony 2

S.No. AUTHOR TITLE 1. Rishi Singh State Formation and the Establishment of Non-Muslim Hegemony 2. Murzban Jal Why we are not Hindus 3. Royina Grewal Babur Conqueror of Hindustan 4. Amartya Sen The Country of First Boys 5. Subodh Roy Chittagong Armoury Raid 6. Ashwin Desai The South African Gandhi 7. Kathryn S. Freeman British women writers and the Asiatic society of Bengal, 1785-1835 8. Toke Lindegaard Knudsen The Siddhantasundara of Jnanaraja 9. Jobin M. Kanjirakkat, ed. Science and narratives of nature : East and West 10. Debjani Sengupta The Partition of Bengal 11. David A.Johnson New Delhi : Te last imperial city 12. Poonam Bala Diaspora, culture and identity 13. T.V.Rajeswar India : The crucial years 14. V.Raghunathan Beyond the call of duty 15. Sagari Chhabra In search of freedom 16. Samir Kumar Das, ed. India democracy and violence 17. Pradeep P.Gokhale Lokayata/Carvaka 18. Naiyer Masud Collected stories 19. Khushwant Singh Portrait of a Serial Killer 20. Amarnath Prasad Women sensibility in Indian women novelists 21. J.P.Losty Picturesque view of India : Sita Ram 22. Neerja Singh Patel, Prasad and Rajaji : Myth of Indian right 23. David Bell Cultural Policy 24. Nirmal Kumar, ed. Essays in Medieval India 25. Peter Frankopan The Silk Roads 26. Tariq Jaffer Razi 27. Fanindam Deo Socio-religious movements and cultural networks in Indian Civilisation 28. Sangeeta Bahadur Vikraal 29. Pravinsinh Chavda Hon’ble minister Jagubhai 30. Paulami Duttagupta A thousand unspoken words 31. Ashish Rajadhyaksha Kumar Shahani : The shock of desire and other essays 32. Danesh Rana Red maize 33. -

1 Minutes of the Meeting of the Executive Council Held on Saturday

1 MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF THE EXECUTIVE COUNCIL HELD ON SATURDAY, THE 3rd NOVEMBER, 2012 AT 2.00 P.M. IN THE COUNCIL ROOM, UNIVERSITY OF DELHI DELHI-110007 No. 5 PRESENT 1. Prof. Dinesh Singh Vice-Chancellor - Chairman 2. Prof. Vivek Suneja Pro-Vice-Chancellor 3. Prof. Sudhish Pachauri Dean of Colleges 4. Prof. Umesh Rai Director, UDSC 5. Dr. Savita M. Dutta Director, C.O.L. 6. Prof. Satwanti Kapoor Proctor 7. Mr. Anurag Shokeen 8. Dr. Deepak Malhotra 9. Mr. Javid Chowdhury 10. Prof. Prabhjot S. Kulkarni 11. Dr. K.S. Bhati 12. Mr. Rajib Ray 13. Prof. S.C. Bhatla 14. Dr. Satender Kumar Joshi 15. Dr. Shiba C. Panda 16. Mr. V.K. Misra 17. Prof. Upreet Dhaliwal SPECIAL INVITEES 1. Prof. Ajay Kumar 2. Prof. J.M. Khurana 3. Prof. Kamala Sankaran 2 4. Sh. R.N. Vashistha 5. Sh. Sanjay Jha 6. Mr. Z.V.S. Prasad Ms. Alka Sharma, Registrar - Secretary WELCOME 34/ At the outset, the Council welcomed the following who had become member of the Executive Council: 1. Prof. Satish Deshpande, Dean, Faculty of Social Sciences 2. Prof. Upreet Dhaliwal , Dean, Faculty Homoeopathy 3. Sh. Vinod Kumar Misra, Visitor’s Nominee 4. Sh. Naveen Chawla, Visitor’s Nominee 5. Sh. Z.V.S. Prasad, Special Invitee APPRECIATION 35/ The Council placed on record its deep sense of gratitude and appreciation for the services rendered by the following during their tenure as member of the Executive Council: 1. Prof. I. Usha Rao, Proctor 2. Prof. H.S. Prasad, Dean, Faculty of Arts 3. -

INDIA INTERNATIONAL CENTRE Volume XXVIII

diary Price Re.1/- INDIA INTERNATIONAL CENTRE volume XXVIII. No. 2 March – April 2014 composed Carnatic music in Hindustani ragas as well as Same Difference NottuSvarams inspired by British band music; in recent MUSIC APPRECIATION PROMOTION: The North–South years, Carnatic ragas such as Hamsadhwani and Convergence in Carnatic and Hindustani Music Charukeshi have been adopted enthusiastically by the Panelists: Subhadra Desai, Saraswati Rajagopalan north; Maharashtrian abhangs have become staples at and Suanshu Khurana Chair: Vidya Shah, March 21 Carnatic concerts; Indian classical music has shown a PERFORMANCE: A Celebration of Carnatic and willingness to naturalise Western imports such as the Hindustani Music violin, guitar, saxophone, mandolin and even the organ. Carnatic Vocal Recital by Sudha Raghunathan So what this really means is that you have two distinct Hindustani Vocal Recital by Meeta Pandit systems, with often disparate ideas about what constitutes Collaboration: Spirit of India, March 22 good music production, but tantalisingly similar lexicons and grammatical constructs that occasionally become the This was a thought-provoking discussion-demonstration basis for some interesting conversations. on the convergence between Carnatic and Hindustani music, two systems divided by a putatively common These insights kept coming to mind the next evening, musical language. The audience certainly converged; as to when the clamour of birdsong at the picturesque Rose the systems, it was largely a revelation of their divergences, Garden heralded performances by Meeta Pandit of the though a very interesting, and at times even amusing one. Gwalior gharana and then Sudha Raghunathan, the Madras Music Academy’s Sangeeta Kalanidhi for this Carnatic training begins with the raga Mayamalavagaula, year. -

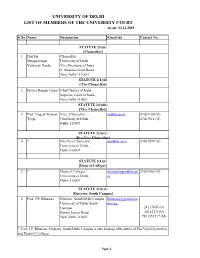

UNIVERSITY of DELHI LIST of MEMBERS of the UNIVERSITY COURT As On: 12.11.2018

UNIVERSITY OF DELHI LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE UNIVERSITY COURT As on: 12.11.2018 S.No Name Designation Email ids Contact No. STATUTE 2(1)(i) [Chancellor] 1 Hon'ble Chancellor Muppavarapu University of Delhi Venkaiah Naidu Vice-President of India 6, Maulana Azad Road, New Delhi - 110011 STATUTE 2(1)(ii) [ Pro-Chancellor] 2 Justice Ranjan Gogoi Chief Justice of India Supreme Court of India New Delhi-110001 STATUTE 2(1)(iii) [Vice-Chancellor] 3 Prof. Yogesh Kumar Vice -Chancellor [email protected] 27001100 (O) Tyagi University of Delhi, 27667011 (O) Delhi-110007 STATUTE 2(1)(iv) [Pro-Vice-Chancellor] 4 * Pro-Vice-Chancellor [email protected] 27667899 (O) University of Delhi, Delhi-110007 STATUTE 2(1)(v) [Dean of Colleges] 5 * Dean of Colleges [email protected]. 27667066 (O) University of Delhi, in Delhi-110007 STATUTE 2(1)(vi) [Director, South Campus] 6 Prof. J.P. Khurana Director, South Delhi Campus khuranaj@genomein University of Delhi South dia.org Campus 24117005 (O) Benito Jaurez Road 24112231(O) New Delhi-110021 9811351217 (M) * Prof. J.P. Khurana, Director, South Delhi Campus is also looking after duties of Pro-Vice-Chancellor and Dean of Colleges Page 1 STATUTE 2(1)(vii) [Tresurer] 7 Shri T.S. Kripanidhi Treasurer kripanidhits@yahoo. 9818928162 University of Delhi co.in Delhi-110007 STATUTE 2(1)(viii) [All Former Vice-Chancellor] 8 Prof. Upendra Baxi A-51, Law Appartments, [email protected] 8447944106 (M) Karkardoma, n Delhi-110092 baxiupendra@gmail. 9 Prof. Vrajendra Raj 5928, DLF Qutab Enclave, 9350292197 (M) Mehta Phase-IV, Gurgaon-122002 10 Prof. -

Alphabetical List of Recommendations Received for Padma Awards - 2014

Alphabetical List of recommendations received for Padma Awards - 2014 Sl. No. Name Recommending Authority 1. Shri Manoj Tibrewal Aakash Shri Sriprakash Jaiswal, Minister of Coal, Govt. of India. 2. Dr. (Smt.) Durga Pathak Aarti 1.Dr. Raman Singh, Chief Minister, Govt. of Chhattisgarh. 2.Shri Madhusudan Yadav, MP, Lok Sabha. 3.Shri Motilal Vora, MP, Rajya Sabha. 4.Shri Nand Kumar Saay, MP, Rajya Sabha. 5.Shri Nirmal Kumar Richhariya, Raipur, Chhattisgarh. 6.Shri N.K. Richarya, Chhattisgarh. 3. Dr. Naheed Abidi Dr. Karan Singh, MP, Rajya Sabha & Padma Vibhushan awardee. 4. Dr. Thomas Abraham Shri Inder Singh, Chairman, Global Organization of People Indian Origin, USA. 5. Dr. Yash Pal Abrol Prof. M.S. Swaminathan, Padma Vibhushan awardee. 6. Shri S.K. Acharigi Self 7. Dr. Subrat Kumar Acharya Padma Award Committee. 8. Shri Achintya Kumar Acharya Self 9. Dr. Hariram Acharya Government of Rajasthan. 10. Guru Shashadhar Acharya Ministry of Culture, Govt. of India. 11. Shri Somnath Adhikary Self 12. Dr. Sunkara Venkata Adinarayana Rao Shri Ganta Srinivasa Rao, Minister for Infrastructure & Investments, Ports, Airporst & Natural Gas, Govt. of Andhra Pradesh. 13. Prof. S.H. Advani Dr. S.K. Rana, Consultant Cardiologist & Physician, Kolkata. 14. Shri Vikas Agarwal Self 15. Prof. Amar Agarwal Shri M. Anandan, MP, Lok Sabha. 16. Shri Apoorv Agarwal 1.Shri Praveen Singh Aron, MP, Lok Sabha. 2.Dr. Arun Kumar Saxena, MLA, Uttar Pradesh. 17. Shri Uttam Prakash Agarwal Dr. Deepak K. Tempe, Dean, Maulana Azad Medical College. 18. Dr. Shekhar Agarwal 1.Dr. Ashok Kumar Walia, Minister of Health & Family Welfare, Higher Education & TTE, Skill Mission/Labour, Irrigation & Floods Control, Govt. -

635301449163371226 IIC ANNUAL REPORT 2013-14 5-3-2014.Pdf

2013-2014 2013 -2014 Annual Report IND I A INTERNAT I ONAL CENTRE 2013-2014 IND I A INTERNAT I ONAL CENTRE New Delhi Board of Trustees Mr. Soli J. Sorabjee, President Justice (Retd.) B.N. Srikrishna Professor M.G.K. Menon Mr. L.K. Joshi Dr. (Smt.) Kapila Vatsyayan Dr. Kavita A. Sharma, Director Mr. N. N. Vohra Executive Members Dr. Kavita A. Sharma, Director Professor Dinesh Singh Mr. K. Raghunath Dr. Biswajit Dhar Dr. (Ms) Sukrita Paul Kumar Cmde.(Retd.) Ravinder Datta, Secretary Cmde.(Retd.) C. Uday Bhaskar Mr. P.R. Sivasubramanian, Hony. Treasurer Mrs. Meera Bhatia Finance Committee Justice (Retd.) B.N. Srikrishna, Dr. Kavita A. Sharma, Director Chairman Mr. P.R. Sivasubramanian, Hony. Treasurer Mr. M. Damodaran Cmde. (Retd.) Ravinder Datta, Secretary Cmde.(Retd.) C. Uday Bhaskar Mr. Ashok K. Chopra, Chief Finance Officer Medical Consultants Dr. K.P. Mathur Dr. Rita Mohan Dr. K.A. Ramachandran Dr. Gita Prakash Dr. Mohammad Qasim IIC Senior Staff Ms Omita Goyal, Chief Editor Mr. A.L. Rawal, Dy. General Manager Dr. S. Majumdar, Chief Librarian Mr. Vijay Kumar, Executive Chef Ms Premola Ghose, Chief, Programme Division Mr. Inder Butalia, Sr. Finance and Accounts Officer Mr. Arun Potdar, Chief, Maintenance Division Ms Hema Gusain, Purchase Officer Mr. Amod K. Dalela, Administration Officer Ms Seema Kohli, Membership Officer Annual Report 2013-2014 It is a privilege to present the 53rd Annual Report of the India International Centre for the period 1 February 2013 to 31 January 2014. The Board of Trustees reconstituted the Finance Committee for the two-year period April 2013 to March 2015 with Justice B.N. -

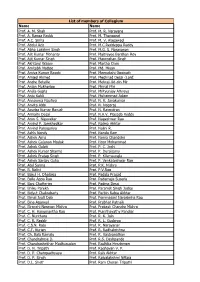

List of Collegium Members of ICSSR.Xlsx

List of members of Collegium Name Name Prof. A. M. Shah Prof. M. R. Narayana Prof. A. Ranga Reddy Prof. M. Thangaraj Prof. A.C. Sinha Prof. M. V. Alagawadi Prof. Abdul Aziz Prof. M.C.Reddeppa Reddy Prof. Abha Lakshmi Singh Prof. M.G. S. Narayanan Prof. Ajit Kumar Mohanty Prof. Maitreyee Bardhan Roy Prof. Ajit Kumar Singh Prof. Manmohan Singh Prof. Akhtarul Wasey Prof. Martha Chen Prof. Amitabh Mattoo Prof. Md. Miyan Prof. Amiya Kumar Bagchi Prof. Meenakshi Gopinath Prof. Amjed Ahmed Prof. Meghnad Desai (Lord) Prof. Andre Beteille Prof. Mehraj-Ud-din Mir Prof. Anjan Mukherjee Prof. Mrinal Miri Prof. Anjila Gupta Prof. Mrityunjay Athreya Prof. Anju Kohli Prof. Muhammad Aslam Prof. Annpurna Nautiyal Prof. N. K. Jayakumar Prof. Anvita Abbi Prof. N. Nagaraj Prof. Apurba Kumar Baruah Prof. N. Rajendran Prof. Armaity Desai Prof. N.A.V. Prasada Reddy Prof. Arun S. Nigavekar Prof. Nageshwar Rao Prof. Arvind P. Jamkhedkar Prof. Najma Akhtar Prof. Arvind Panagariya Prof. Nalini R. Prof. Ashis Nandy Prof. Nandu Ram Prof. Ashok Aima Prof. Neera Chandoke Prof. Ashok Gajanan Modak Prof. Noor Mohammad Prof. Ashok Gulati Prof. P. C. Joshi Prof. Ashok Kumar Sharma Prof. P. Duraisamy Prof. Ashok Pratap Singh Prof. P. Kilemsungla Prof. Ashok Sanjay Guha Prof. P. Venkateshwar Rao Prof. Atul Sarma Prof. P.K. Mishra Prof. B. Nalini Prof. P.V.Rao Prof. Bakul H. Dholakia Prof. Padala Prasad Prof. Balla Appa Rao Prof. Padamaja Susarla Prof. Bani Chatterjee Prof. Padma Desai Prof. Bhiku Parekh Prof. Paramjit Singh Judge Prof. Bidyut Chakrabarty Prof. Parbin Rabia Akhtar Prof. -

Annual Report April 2015 – March 2016

. INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS Annual Report April 2015 – March 2016 :1: Contents S. No. Particulars Page No. 1 INTRODUCTION AND SYNOPSIS 4-5 2 HIGHLIGHTS OF THE YEAR 2015-2016 6-7 3 THE ACTIVITIES OF THE COUNCIL (i) Scholarships and Welfare of International Students 7-8 (ii) Indian Cultural Centres Abroad 9-10 (iii) Chairs of Indian Studies abroad 10-11 (iv) Conferences and Seminars 11 (v) Fellowships 11-12 (vi) Outgoing /Academic Visitors Programme 12 (vii) Busts/Statutes 12 (viii) Forum of Friends of ICCR (FFOI) 13 (ix) Outgoing Cultural Delegations/Festivals abroad 13-14 (x) Incoming Cultural Delegations and Cultural Performances by 15-17 Indian artistes in India (xi) Foreign Cultural Centres 17-18 (xii) Distinguished/Important Visitors Programme 18 (xiii) Exhibitions 19 (xiv) Publications 19 (xv) Hindi and Related Activities 20 (xvi) Library 21-22 (xvii) Regional Offices 22-23 (xviii) Awards 23 4 ACCOUNTS 24-25 5 FUTURE PLANS (2016-17) 26-27 :2: LIST OF ANNEXURES (i) List of General Assembly Members of the ICCR 28-34 (ii) List of Governing Body Members of the ICCR 35-36 (iii) List of Finance Committee Members of the ICCR 37 (iv) Details of Scholarships 38 (v) Indian Cultural Centres Abroad 39-40 (v) (i) List of Missions provided Yoga Teachers as Resource Persons 41 on long term basis (vi) Chairs of Indian Studies Abroad 42-46 (vii) Conferences and Seminars 47-49 (viii) Outgoing/ Academic Visitors Programme 50-52 (ix) Busts/Statues 53 (x) Outgoing Cultural Delegations 54-72 (xi) Incoming Cultural Delegations and Cultural Performances by 73-77 Indian artistes in India (xii) Distinguished Visitors Programme/ Important Visitors 78-79 Programme (xiii) Exhibitions 80-82 (xiv) List of Regional Offices of the ICCR 83-84 :3: 1. -

History, Philosophy, and Religion 2020-21

2020–21 History, Philosophy, Religion 1 Pg Pg Pg 43 43 18 Poetry of Belonging Krishna's Playground Narrative Past Ali Khan Mahumudabad John Stratton Hawley Jyoti Gulati Balachandran 9780190121013 9780190123987 9780190123994 Pg 82 Narrating South Asian Buddhism Classical Indian Partition Philosophy Dale S. Wright Peter Adamson Anindya Raychaudri 9780197534335 Jonardon Ganeri 9780197500347 9780198851769 1 2 Table of Contents General / Reference.................................................04 The Oxford India Collection.....................................09 Archaeology and Ancient India...............................10 Medieval India.........................................................13 Modern Indian History............................................20 India and South Asia...............................................44 Ecology and Environment........................................46 History of Science and Technology..........................47 History of Art and Architecture...............................48 Oxford India Perennials...........................................48 Towards Freedom....................................................49 Debates in Indian History and Society.....................50 Themes in Indian History.........................................52 Monumental Legacy................................................54 Makers of Islamic Civilization..................................56 Regional Studies: North east India..........................58 Regional Studies: South India..................................59 -

Annual Report 2019-2020

Indian Council of Social Science Research North-Eastern Regional Centre Forty-Third Annual Report ICSSR-NERC 2019-2020 Printed at : Modern Off set, Wahthapbroo, Shillong - 2, Meghalaya, : 0364-2243437, E-mail : modernoff [email protected] ii Annual Report - 2019-2020 CONTENTS Chapter Page No. Foreword .................................................................................................................................................. v Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 1-2 1. Seminars, Workshops, Conferences ................................................................................... 3 - 98 1.1 Seminars sponsored by the NERC ........................................................................................ 3 1.2 Seminars organized by the NERC ...................................................................................... 97 2. Services Rendered to Scholars ..........................................................................................98-102 2.1 Study Grant ..............................................................................................................................98 2.2 Contingency Grant for Doctoral Scholars ........................................................................99 2.3 Research Projects ................................................................................................................. 101 3. Lectures .............................................................................................................................................. -

India and Its Northeast Exception: from Frontier to Forefront

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2015 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2015 India and Its Northeast Exception: From Frontier to Forefront Akshita Manjari Bhanjdeo Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2015 Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, and the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Recommended Citation Bhanjdeo, Akshita Manjari, "India and Its Northeast Exception: From Frontier to Forefront" (2015). Senior Projects Spring 2015. 118. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2015/118 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. India and Its Northeast Exception: From Frontier to Forefront Senior Project Submitted to The Division of Social Studies of Bard College by Akshita Manjari Bhanj Deo Annandale-on-Hudson, New York May 2015 Dedication In my last year of high school, while aimlessly searching for something on the Internet, I came across a Google image of a Manipuri woman sitting on the side of the street in New Delhi. -

Mrinal Miri Was Born in Shillong in the Year 1940. He Went to Various Small Town Schools in Assam

Mrinal Miri was born in Shillong in the year 1940. He went to various small town schools in Assam. After his schooling he went to Presidency College Calcutta, to read for his B.A (H) degree in philosophy. He then took his M.A degree in philosophy from St. Stephen’s College, Delhi. In 1964, Miri went, on a scholarship, to Cambridge where he took his tripos (in philosophy) and the Ph.D degree under the supervision of the Late Professor Bernard Williams. He returned to Delhi in 1970 to teach in St. Stephen’s College. In 1974 he moved to Shillong to set up the department of philosophy in the newly established central university (North Eastern Hill University). He retired as the Vice- Chancellor of this university in 2005. He has lived in Delhi since then. Prior to becoming Vice-Chancellor he was Director of the Indian Institute of Advanced Study at Shimla from 1993 to 1999. Professor Miri has been a member of bodies like the University Grants Commission, Indian Council of Social Science Research and Indian Council of Philosophical Research (ICPR). He has also been the Chairman of the Indian Council of Philosophical Research (1994-1997). He has been Visiting Professor in several universities. In 2008, Miri was appointed the Chairman of the Forum of the Vice Chancellors of the Central Universities of the North-Eastern Region by the Government of India. He is the Chairman of the Centre for Studies of Developing Societies (CSDS). He is also a member of the Central Advisory Board of Education.