How Planer Settings Affect Timber Properties

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comparative Study of NZ Pine & Selected SE Asian Species

(FRONT COVER) A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF NEW ZEALAND PINE AND SELECTED SOUTH EAST ASIAN SPECIES (INSIDE FRONT COVER) NEW ZEALAND PINE - A RENEWABLE RESOURCE NZ pine (Pinus radiata D. Don) was introduced to New Zealand (NZ) from the USA about 150 years ago and has gained a dominant position in the New Zealand forest industry - gradually replacing timber from natural forests and establishing a reputation in international trade. The current log production from New Zealand forests (1998) is 17 million m3, of which a very significant proportion (40%) is exported as wood products of some kind. Estimates of future production indicate that by the year 2015 the total forest harvest could be about 35 million m3. NZ pine is therefore likely to be a major source of wood for Asian wood manufacturers. This brochure has been produced to give prospective wood users an appreciation of the most important woodworking characteristics for high value uses. Sponsored by: Wood New Zealand Ltd. Funded by: New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade Written by: New Zealand Forest Research Institute Ltd. (Front page - First sheet)) NEW ZEALAND PINE - A VERSATILE TIMBER NZ pine (Pinus radiata D.Don) from New Zealand is one of the world’s most versatile softwoods - an ideal material for a wide range of commercial applications. Not only is the supply from sustainable plantations increasing, but the status of the lumber as a high quality resource has been endorsed by a recent comparison with six selected timber species from South East Asia. These species were chosen because they have similar end uses to NZ pine. -

Performance, Technology and Application of High Performance Marine Vessels Volume One

Performance, Technology and Application of High Performance Marine Vessels Volume One Performance, Technology and Application of High Performance Marine Vessels Volume One Edited by Liang Yun, Raju Datla and Xinfa Yang Performance, Technology and Application of High Performance Marine Vessels Volume One Edited by Liang Yun, Raju Datla and Xinfa Yang This book first published 2018 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2018 by Liang Yun, Raju Datla, Xinfa Yang and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-0356-9 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-0356-4 CONTENTS Preface by the Editors-in-Chief ................................................................. xii Liang Yun, Raju Datla, Xinfa Yang Preface .................................................................................................... xxiv Trevor Blakeley Preface .................................................................................................... xxvi Guo Da-cheng Preface .................................................................................................. xxviii Huang Ping-tao Preface .................................................................................................... -

Discoloration of Norway Spruce and Scots Pine Timber During Drying

Discoloration of Norway spruce and Scots pine timber during drying V. Tarvainen VTT Building and Transport, Puumiehenk. 2A Espoo, P.O.Box 1806 FIN-02044 VTT, Finland. Internet: [email protected] P. Saranpää Metla - The Finnish Forest Research Institute, J. Repola P.O. Box 18, FIN-01301 VANTAA, Finland Internet: [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT The effect of growth site, felling time (winter, spring and autumn) and wet storage on the discoloration of spruce (Picea abies (L.) Karst.) and pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) dried at different temperatures was studied. Two dominant trees were selected at each cutting season from a fertile and a poor site. Some of the logs felled in May were stored under sprinklers for 6 weeks. The butt logs were cant-sawn with a circular saw. The temperatures for drying were 50, 70, 90 and 110 °C. One group from autumn felling was dried in a vacuum kiln at 70 °C. Common drying schedules for 38-mm-thick pine boards were used. The surface colour (CIELAB L*, a*, b*) of boards was measured before and after drying with a spectrophotometer. Some of the boards were also measured after 0.5 mm and further 1.5 mm planing. Drying temperature was the most significant factor for discoloration of boards. The colour change of pine was quite similar to that of spruce except that there was a stronger darkening of pine heartwood compared to spruce at 90 °C. Discoloration in sapwood increased remarkably at temperatures above 70 °C. At 90 and 110 °C the lightness (L*) decreased significantly indicating darkening. -

Variation of Basic Density and Brinell Hardness Within Mature Finnish Betula Pendula and B

VARIATION OF BASIC DENSITY AND BRINELL HARDNESS WITHIN MATURE FINNISH BETULA PENDULA AND B. PUBESCENS STEMS Henrik Herujarvi Research Scientist Finnish Forest Research Institute Joensuu Research Centre P.O. Box 68 FIN-80101 Joensuu, Finland (Received November 200 1 ) ABSTRACT Thc objective of this study was to analyze the variation in basic density between different horizontal and vertical locations within mature Finnish Betula pendula and B. puhescens stems. In addition, the depen- dence of Brinell hardness in radial direction, which is of importance especially for the parquetry, veneer. and plywood industries, on the basic density was investigated. Furthermore, the sources of error in the Brinell hardness test according to EN 1534 were analyzed. Both basic density and Brinell hardness were measured from small. defect-free specimens. The average basic density of B. pendula and B. pubescerz.s were 5 12 kg/m3 and 478 kg/m3, respectively. Concerning both birch species, wood material near the pith was clearly less dense than near the surface of the stem. The average Brinell hardness of B. pendula spec- irnens was 23.4 MPa, and that of B. pubescens specimens was 20.5 MPa. Brinell hardness was found to be positively correlated with basic density. Therefore, the assumption that Brinell hardness varies within a birch stem similarly to basic density is confirmed. The test method according to the EN 1534 standard was found to hc precise enough hut unnecessarily laborious for hardness tests. Finally, an alternative method is s~~ggestedfor determining Brinell hardness on an industrial scale. Kryw,orti.c: Basic density. Brinell hardness, Betula pendul(~,Beruln puhescens, furnishing, parquet, veneer, plywood. -

Remoistening of the Wood Before Planing -A Method for Improved Surface Quality?

REMOISTENING OF THE WOOD BEFORE PLANING -A METHOD FOR IMPROVED SURFACE QUALITY? Micael Öhman , Victor Grubîi , Mats Ekevad Luleå University of Technology, Skellefteå, Sweden [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT It is beneficial if the machining of wooden products is done at a moisture content equal to the climate the product is meant to be used in. For indoor products in central heated houses such moisture content is about 5-10%. For planing this is often a too low moisture content showing an increased risk of poor surface quality due to severe torn grain. Contrary to this too high moisture content will result in a fuzzy grain surface and problems with swelling and shrinkage of the product. The roughness of a machined wooden surface is affected by a number of different parameters like cutting tool geometry, machine settings and wood structure. The latter is the hardest to control since the surface quality is a result of the local combination of density, grain direction and moisture content. The larger the variation in wood features the more difficult it is to find a combination of tools and machine settings that will give a high surface quality. This study showed that by wetting the surface before machining, in this case planing, the average surface quality could be increased. No time dependences could be shown, wetting short before planing did show as good improvements as wetting treatment for 30 minutes or more. The study was based on a total of 120 test surfaces of Scots pine (Pinus silvestris L.). -

Potential for Waste Reduction When Planing Wood

KES Transactions on Sustainable Design and Manufacturing I Sustainable Design and Manufacturing 2014 : pp.18-25 : Paper sdm14-021 Potential for waste reduction when planing wood Ann Axelsson1, Magnus Fredriksson2 1Luleå University of Technology, Campus Skellefteå, 931 87 Skellefteå, Sweden [email protected] 2Luleå University of Technology, Campus Skellefteå, 931 87 Skellefteå, Sweden [email protected] Abstract In Swedish sawmills, only half of the raw material becomes the planks and boards that is their main products. The rest turn into wood chips, saw dust and shavings. This study has investigated the potential to reduce waste simply by reducing the green target dimensions for the centre yield planks that are to be planed. It turned out that there are possibilities to reduce the green target thickness with 2.6 mm and the green target width with 3.8 mm for planks. The reduction would increase the volume yield with 0.5 % which roughly corresponds to 20,000 m3 timber in Sweden per year. 1. Introduction Many people visiting Sweden, and especially the northern part of the country gets struck by the abundance of forests, especially coniferous (softwood) forests. It is not surprising as less than 5 % of the total land area is populated. The majority of the country consists of productive forest land, about 57 %, with 3.0 billion m3 standing volume of wood [1]. In addition, there are also 8 % mountains and alpine coniferous forest. The wood is used for production of construction material, packaging, pulp, paper and energy (Figure 1). Nearly 60,000 individuals are employed in the forest industry alone and if also employees of sub-contractors are included, the number of jobs becomes nearly 200,000 which roughly correspond to 35 % of the total amount of employees in Swedish industry [2]. -

Planing and Profiling

Anpassung der Rückenstärke für Druck noch nicht ausgeführt Planing and profiling Leitz Lexicon Edition 7 Version 2 Explanation of abbreviations A = dimension A LH = left hand rotation ae = cutting thickness (radial) ap = cutting depth (axial) M = metric thread ABM = dimension MBM = minimum order quantity APL = panel raising length MC = multi-purpose steel, coated APT = panel raising depth MD = thickness of knife AL = working length min-1 = revolutions per minute (RPM) AM = number of knives MK = morse taper AS = anti sound (low noise design) m min-1 = metres per minute m s-1 = metres per second b = overhang B = width n = RPM BDD = thickness of shoulder nmax. = maximum permissible RPM BEM = note NAL = position of hub BEZ = description ND = thickness of hub BH = tipping height NH = zero height BO = bore diameter NL = cutting length NLA = pinhole dimensions CNC = Computerized Numerical Control NT = grooving depth d = diameter P = profile D = cutting circle diameter POS = cutter position D0 = zero diameter PT = profile depth DA = outside Diameter PG = profile group DB = diameter of shoulder DFC = Dust Flow Control (optimised chip clearance) QAL = cutting material quality DGL = number of links DIK = thickness R = radius DKN = double keyway RD = right hand twist DP = polycrystalline diamond RH = right hand rotation DRI = rotation RP = radius of cutter FAB = width of rebate S = shank dimension FAT = depth of rebate SB = cutting width FAW = bevel angle SET = set FLD = flange diameter SLB = slotting width fz = tooth feed SLL = slotting length fz eff = effective tooth feed SLT = slotting depth SP = tool steel GEW = thread ST = Cobalt-basis cast alloys, GL = total length e.g. -

Wood from Midwestern Trees Purdue EXTENSION

PURDUE EXTENSION FNR-270 Daniel L. Cassens Professor, Wood Products Eva Haviarova Assistant Professor, Wood Science Sally Weeks Dendrology Laboratory Manager Department of Forestry and Natural Resources Purdue University Indiana and the Midwestern land, but the remaining areas soon states are home to a diverse array reforested themselves with young of tree species. In total there are stands of trees, many of which have approximately 100 native tree been harvested and replaced by yet species and 150 shrub species. another generation of trees. This Indiana is a long state, and because continuous process testifies to the of that, species composition changes renewability of the wood resource significantly from north to south. and the ecosystem associated with it. A number of species such as bald Today, the wood manufacturing cypress (Taxodium distichum), cherry sector ranks first among all bark, and overcup oak (Quercus agricultural commodities in terms pagoda and Q. lyrata) respectively are of economic impact. Indiana forests native only to the Ohio Valley region provide jobs to nearly 50,000 and areas further south; whereas, individuals and add about $2.75 northern Indiana has several species billion dollars to the state’s economy. such as tamarack (Larix laricina), There are not as many lumber quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides), categories as there are species of and jack pine (Pinus banksiana) that trees. Once trees from the same are more commonly associated with genus, or taxon, such as ash, white the upper Great Lake states. oak, or red oak are processed into In urban environments, native lumber, there is no way to separate species provide shade and diversity the woods of individual species. -

Thickness Planer

PLANING, MOULDING & PROFILING MACHINES Thickness Planer v1 – 2009 © BWF / DIDAC ONLY TRAINED AND AUTHORISED PERSONS TO USE THIS MACHINE • This machine is to be used for planing timber to size SAFE USE PROCEDURES • Only feed single pieces of timber where solid feed rollers are fitted • Do not stand in line with timber when feeding the machine • Do not make heavy cuts • Report any machine defects immediately to your supervisor • Use support tables when feeding long lengths of timber • Do not leave the machine unattended whilst the cutter(s) is in motion or running down • Report any faults with the machine, guards or dust extraction to your supervisor immediately • Machine must stop within 10 seconds • The machine MUST NOT be left unattended • Ensure working area around the machine is kept clear at all times • Ensure correct use of Local Extraction Ventilation system • Use appropriate PPE when required • Use correct manual handling techniques at all times MACHINE MAINTENANCE & CLEANING • DO NOT clean machine whilst still in motion • Ensure all maintenance is carried out following the machine manufacturer’s instructions LIMITATIONS • Do not use for small lengths that will not be fed through the machine This is one of a series of guides printed by the BWF. Further copies are available from British Woodworking Federation Tel: 0844 209 2610 Fax: 0844 209 2611 BWF WOODWORKING MACHINERY SAFETY CARD NO 21 21 CARD NO SAFETY BWFMACHINERY WOODWORKING e-mail: [email protected] ABOUT THE BWF The British Woodworking Federation is the leading representative body for the woodworking and joinery manufacturing industry in the UK. -

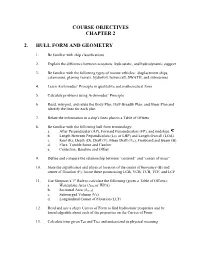

Course Objectives Chapter 2 2. Hull Form and Geometry

COURSE OBJECTIVES CHAPTER 2 2. HULL FORM AND GEOMETRY 1. Be familiar with ship classifications 2. Explain the difference between aerostatic, hydrostatic, and hydrodynamic support 3. Be familiar with the following types of marine vehicles: displacement ships, catamarans, planing vessels, hydrofoil, hovercraft, SWATH, and submarines 4. Learn Archimedes’ Principle in qualitative and mathematical form 5. Calculate problems using Archimedes’ Principle 6. Read, interpret, and relate the Body Plan, Half-Breadth Plan, and Sheer Plan and identify the lines for each plan 7. Relate the information in a ship's lines plan to a Table of Offsets 8. Be familiar with the following hull form terminology: a. After Perpendicular (AP), Forward Perpendiculars (FP), and midships, b. Length Between Perpendiculars (LPP or LBP) and Length Overall (LOA) c. Keel (K), Depth (D), Draft (T), Mean Draft (Tm), Freeboard and Beam (B) d. Flare, Tumble home and Camber e. Centerline, Baseline and Offset 9. Define and compare the relationship between “centroid” and “center of mass” 10. State the significance and physical location of the center of buoyancy (B) and center of flotation (F); locate these points using LCB, VCB, TCB, TCF, and LCF st 11. Use Simpson’s 1 Rule to calculate the following (given a Table of Offsets): a. Waterplane Area (Awp or WPA) b. Sectional Area (Asect) c. Submerged Volume (∇S) d. Longitudinal Center of Flotation (LCF) 12. Read and use a ship's Curves of Form to find hydrostatic properties and be knowledgeable about each of the properties on the Curves of Form 13. Calculate trim given Taft and Tfwd and understand its physical meaning i 2.1 Introduction to Ships and Naval Engineering Ships are the single most expensive product a nation produces for defense, commerce, research, or nearly any other function. -

Janka Hardness Using Nonstandard Specimens

United States Department of Agriculture Janka Hardness Using Forest Service Nonstandard Specimens Forest Products Laboratory Research David W. Green Note Marshall Begel FPL–RN–0303 William Nelson Abstract Contents Janka hardness determined on 1.5- by 3.5-in. specimens Executive Summary ............................................................. i (2×4s) was found to be equivalent to that determined using Introduction ..........................................................................1 the 2- by 2-in. specimen specified in ASTM D 143. Data are Background ..........................................................................1 presented on the relationship between Janka hardness and History of Standardization ...............................................1 the strength of clear wood. Analysis of historical data de- Relationship of Janka Hardness to Other Properties ........2 termined using standard specimens indicated no difference Strength Properties .......................................................2 between side hardness values determined on the radial face Specific Gravity ...........................................................3 as opposed to the tangential. Analysis of historical data also Load Placement and Specimen Thickness ...................4 indicated that the relationship between hardness modulus Growth Ring Orientation .............................................4 (HM) and Janka hardness (H) may be different for hardwood Moisture Content .........................................................5 species -

Common Hand Tools

Common Hand Tools Lesson 1: Common Hand Tools for Common Measurement Tools Woodworking Measurement tools are used to ensure accuracy and Before beginning a woodworking project, workers must consistency of a project. They are used for determining be familiar with shop safety rules and knowledgeable linear measurements such as length and width and area about common hand tools. Hand tools are usually measurements such as square feet. They are also used used for smaller projects or where power tools or for checking if work is square or level. Some common machines would be inefficient. For example, when measurement tools are as follows. The basics are smoothing a small piece of lumber, a hand plane is introduced here and more information is provided more practical than a power plane. An agricultural in Unit III, Lesson 1: Common Measurements and mechanics shop should have a good selection of hand Measurement Tools. tools to accommodate a large variety of woodworking projects. A tape measure is typically used for making straight measurements and taking measurements around Basic Shop Safety Procedures objects (circumference). Tape measures are available that use the U.S. customary system, metric system, and The following are general safety procedures that apply a combination of the two systems. See Figure 1.1. to almost every work situation. • Adhere to instructions. o Read labels and warnings on containers and tools. Figure 1.1 - Tape Measures o Follow the manufacturer’s recommendations for use and maintenance of a specific tool. o Pay attention to signs posted in the work area. o Follow the instructor’s directions.