Moldova by Sergiu Miscoiu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Continuitate Și Discontinuitate În Reformarea Organizării Teritoriale a Puterii Locale Din Republica Moldova Cornea, Sergiu

www.ssoar.info Continuitate și discontinuitate în reformarea organizării teritoriale a puterii locale din Republica Moldova Cornea, Sergiu Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Sammelwerksbeitrag / collection article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Cornea, S. (2018). Continuitate și discontinuitate în reformarea organizării teritoriale a puterii locale din Republica Moldova. In C. Manolache (Ed.), Reconstituiri Istorice: civilizație, valori, paradigme, personalități: In Honorem academician Valeriu Pasat (pp. 504-546). Chișinău: Biblioteca Științifică "A.Lupan". https://nbn-resolving.org/ urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-65461-2 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC Lizenz (Namensnennung- This document is made available under a CC BY-NC Licence Nicht-kommerziell) zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu (Attribution-NonCommercial). For more Information see: den CC-Lizenzen finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/deed.de MINISTERUL EDUCAȚIEI, CULTURII ȘI CERCETĂRII AL REPUBLICII MOLDOVA MINISTERUL EDUCAȚIEI, CULTURII ȘI CERCETĂRII AL REPUBLICII MOLDOVA INSTITUTUL DE ISTORIE INSTITUTUL DE ISTORIE BIBLIOTECA LUPAN” BIBLIOTECA LUPAN” Biblioteca Științică Biblioteca Științică Secția editorial-poligracă Secția editorial-poligracă Chișinău, 2018 Chișinău, 2018 Lucrarea a fost discutată și recomandată pentru editare la şedinţa Consiliului ştiinţific al Institutului de Istorie, proces-verbal nr. 8 din 20 noiembrie 2018 şi la şedinţa Consiliului ştiinţific al Bibliotecii Științifice (Institut) „Andrei Lupan”, proces-verbal nr. 16 din 6 noiembrie 2018 Editor: dr. hab. în științe politice Constantin Manolache Coordonatori: dr. hab. în istorie Gheorghe Cojocaru, dr. hab. în istorie Nicolae Enciu Responsabili de ediție: dr. în istorie Ion Valer Xenofontov, dr. în istorie Silvia Corlăteanu-Granciuc Redactori: Vlad Pohilă, dr. -

Moldova: from Oligarchic Pluralism to Plahotniuc's Hegemony

Centre for Eastern Studies NUMBER 208 | 07.04.2016 www.osw.waw.pl Moldova: from oligarchic pluralism to Plahotniuc’s hegemony Kamil Całus Moldova’s political system took shape due to the six-year rule of the Alliance for European Integration coalition but it has undergone a major transformation over the past six months. Resorting to skilful political manoeuvring and capitalising on his control over the Moldovan judiciary system, Vlad Plahotniuc, one of the leaders of the nominally pro-European Democra- tic Party and the richest person in the country, was able to bring about the arrest of his main political competitor, the former prime minister Vlad Filat, in October 2015. Then he pushed through the nomination of his trusted aide, Pavel Filip, for prime minister. In effect, Plahot- niuc has concentrated political and business influence in his own hands on a scale unseen so far in Moldova’s history since 1991. All this indicates that he already not only controls the judi- ciary, the anti-corruption institutions, the Constitutional Court and the economic structures, but has also subordinated the greater part of parliament and is rapidly tightening his grip on the section of the state apparatus which until recently was influenced by Filat. Plahotniuc, whose power and position depends directly on his control of the state apparatus and financial flows in Moldova, is not interested in a structural transformation of the country or in implementing any thorough reforms; this includes the Association Agreement with the EU. This means that as his significance grows, the symbolic actions so far taken with the aim of a structural transformation of the country will become even more superficial. -

OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights Election Observation Mission Republic of Moldova Parliamentary Elections, 24 February 2019

OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights Election Observation Mission Republic of Moldova Parliamentary Elections, 24 February 2019 INTERIM REPORT 15 January – 4 February 2019 8 February 2019 I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • The 24 February parliamentary elections will be the first held under the newly introduced mixed electoral system with 50 members of parliament (MPs) elected through proportional closed lists in a single nationwide constituency and 51 MPs elected in single member majoritarian constituencies. ODIHR and the European Commission for Democracy through Law (Venice Commission) have previously raised concerns about the lack of an inclusive public debate and consultation during the change to the mixed system and because the issue polarized public opinion and did not achieve a broad consensus. • Significant amendments were made to the Election Code in 2017 to reflect the mixed electoral system, improve regulation of financing, and to introduce a number of other changes. Observation by ODIHR EOM to date has showed that some ambiguities in the legal framework remain open to interpretation. • Three levels of election administration are responsible for organizing the elections: the Central Election Commission (CEC), 51 District Electoral Councils (DECs) and 2,143 Precinct Electoral Bureaus (PEBs). The CEC established 125 polling stations in 37 countries for out-of-country voting and designated 47 polling stations on the government controlled territory for voters in Transniestria. CEC and DEC sessions have so far been open to observers and published their decisions on-line. The CEC is undertaking an extensive training programme for election officials and other stakeholders, including on ensuring voting rights of people with disabilities, and a voter information campaign focused on the specifics of the new electoral system. -

E-Journal, Year IX, Issue 176, October 1-31, 2011

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Policy Documentation Center Governance and democracy in Moldova e-journal, year IX, issue 176, October 1-31, 2011 "Governance and Democracy in Moldova" is a bi-weekly journal produced by the Association for Participatory Democracy ADEPT, which tackles the quality of governance and reflects the evolution of political and democratic processes in the Republic of Moldova. The publication is issued with financial support from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, in framework of the project "Promoting Good Governance through Monitoring". Opinions expressed in the published articles do not necessarily represent also the point of view of the sponsor. The responsibility for the veracity of statements rests solely with the articles' authors. CONTENTS I. ACTIVITY OF PUBLIC INSTITUTIONS........................................................................................................ 3 GOVERNMENT ................................................................................................................................................ 3 1. Events of major importance ...................................................................................................................... 3 Premier’s report regarding assaults on share stocks of some banks ........................................................ 3 2. Nominations. Dismissals .......................................................................................................................... -

Moldova Is Strongly Marked by Self-Censorship and Partisanship

For economic or political reasons, journalism in Moldova is strongly marked by self-censorship and partisanship. A significant part of the population, especially those living in the villages, does not have access to a variety of information sources due to poverty. Profitable media still represent an exception rather than the rule. MoldoVA 166 MEDIA SUSTAINABILITY INDEX 2009 INTRODUCTION OVERALL SCORE: 1.81 M Parliamentary elections will take place at the beginning of 2009, which made 2008 a pre-election year. Although the Republic of Moldova has not managed to fulfill all of the EU-Moldova Action Plan commitments (which expired in February 2008), especially those concerning the independence of both the oldo Pmass media and judiciary, the Communist government has been trying to begin negotiations over a new agreement with the EU. This final agreement should lead to the establishment of more advanced relations compared to the current status of being simply an EU neighbor. On the other hand, steps have been taken to establish closer relations with Russia, which sought to improve its global image in the wake of its war with Georgia by addressing the Transnistria issue. Moldovan V authorities hoped that new Russian president Dmitri Medvedev would exert pressure upon Transnistria’s separatist leaders to accept the settlement project proposed by Chişinău. If this would have occurred, A the future parliamentary elections would have taken place throughout the entire territory of Moldova, including Transnistria. But this did not happen: Russia suggested that Moldova reconsider the settlement plan proposed in 2003 by Moscow, which stipulated, among other things, continuing deployment of Russian troops in Moldova in spite of commitments to withdraw them made at the 1999 OSCE summit. -

Studia Politica 1 2016

www.ssoar.info Republic of Moldova: the year 2015 in politics Goșu, Armand Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Goșu, A. (2016). Republic of Moldova: the year 2015 in politics. Studia Politica: Romanian Political Science Review, 16(1), 21-51. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-51666-3 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de Republic of Moldova The Year 2015 in Politics ARMAND GO ȘU Nothing will be the same from now on. 2015 is not only a lost, failed year, it is a loop in which Moldova is stuck without hope. It is the year of the “theft of the century”, the defrauding of three banks, the Savings Bank, Unibank, and the Social Bank, a theft totaling one billion dollars, under the benevolent gaze of the National Bank, the Ministry of Finance, the General Prosecutor's Office, the National Anti-Corruption Council, and the Security and Intelligence Service (SIS). 2015 was the year when controversial oligarch Vlad Plakhotniuk became Moldova's international brand, identified by more and more chancelleries as a source of evil 1. But 2015 is also the year of budding hope that civil society is awakening, that the political scene is evolving not only for the worse, but for the better too, that in the public square untarnished personalities would appear, new and charismatic figures around which one could build an alternative to the present political parties. -

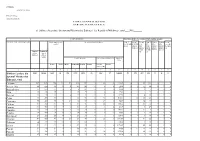

Raport Statistic 2009

Destinaţia ________________________________ _ denumirea şi adresa Cine prezintă_ denumirea şi adresa T A B E L C E N T R A L I Z A T O R D Ă R I D E S E A M Ă A N U A L E ale bibliotecilor şcolare din sistemul Ministerului Educaţiei din Republicii Moldova pe anul ___2009_______ I. DATE GENERALE Repartizarea bibliotecilor conform mărimii colecţiilor (numărul) T I P U R I D E B I B L I O T E C I Forma organizatorico- Din numărul total de biblioteci Categ. 1 Categ. 2 Categ. 3 Categ. 4 Categ. 5 Categ. 6. Categ. 7 juridică până la 2000 de la 2001 de la de la de la de la mai mult de vol. până la 5001 10.001 100.001 500.001 de 1 mln. 5000 vol până la până la până la până la 1 vol 10.000 100.000 500.000 mln. vol Numărul Numărul de vol vol total de locuri în biblioteci sălile de lectură Localul bibliotecii Starea tehnică a bibliotecilor Suprafaţa totală De stat Privată Special Reamenajat Propriu Arendat Necesită Avariat reparaţii capit. A 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Biblioteci şcolare din 1453 15845 1438 15 180 1273 1428 25 516 17 74555 29 170 431 823 0 0 0 sistemul Ministerului Educaţiei, total Chişinău 167 2839 154 13 51 116 159 8 68 1 11809 4 5 35 123 0 0 0 Anenii -Noi 36 429 36 0 5 31 36 0 6 1 2139 3 2 12 19 0 0 0 Basarabeasca 11 214 11 0 5 6 11 0 0 0 760,2 0 1 3 7 0 0 0 Bălţi 25 376 25 0 0 25 25 0 0 0 1764 0 0 1 24 0 0 0 Briceni 33 330 33 0 4 29 33 0 8 0 1327,3 3 0 4 26 0 0 0 Cahul 58 473 58 0 0 58 58 0 58 0 3023,1 1 26 10 21 0 0 0 Cantemir 35 449 35 0 21 14 35 0 29 0 1429 0 4 14 17 0 0 0 Călăraş 41 392 41 0 0 41 41 0 38 0 -

30 January 2014 OSCE Special Representative for Transdniestrian

Press release – OSCE Special Representative – 30 January 2014 OSCE Special Representative for Transdniestrian settlement process visits region ahead of official 5+2 talks The Special Representative of the Swiss OSCE Chairperson-in-Office for the Transdniestrian settlement process, Ambassador Radojko Bogojević, at a the press conference in Chisinau, 30 January 2014. (OSCE/Igor Schimbator) CHISINAU, 30 January 2014 – The Special Representative of the Swiss OSCE Chairperson- in-Office for the Transdniestrian settlement process, Ambassador Radojko Bogojević, today concluded a four-day visit to the region, which included meetings with the political leadership in Chisinau and Tiraspol. This was the first visit by Bogojević to the region in his role as Special Representative. He took up the position this January and will hold it throughout the consecutive Swiss and Serbian Chairmanships in 2014-2015. In Chisinau, Bogojević met Moldovan President Nicolae Timofti, Prime Minister Iurie Leanca, Deputy Prime Minister for Reintegration and Chief Negotiator Eugen Carpov, Deputy Foreign Minister Valeriu Chiveri and Speaker of the Parliament Igor Corman. In Tiraspol, Bogojević met Transdniestrian leader Yevgeniy Shevchuk, Chief Negotiator Nina Shtanski and the Speaker of the Supreme Soviet Mikhail Burla. “Preparations for the next round of the 5+2 talks on the Transdniestrian settlement process to take place on 27 and 28 February in Vienna were the key topic of our discussions, and I was encouraged by the constructive attitude of the sides and their focus -

1 DEZBATERI PARLAMENTARE Parlamentul Republicii Moldova De

DEZBATERI PARLAMENTARE Parlamentul Republicii Moldova de legislatura a XIX-a SESIUNEA a VII-a ORDINARĂ – SEPTEMBRIE 2013 Ședința din ziua de 26 septembrie 2013 (STENOGRAMA) SUMAR 1. Declararea deschiderii sesiunii de toamnă și a ședinței plenare. Intonarea Imnului de Stat al Republicii Moldova. (Intonarea Imnului de Stat al Republicii Moldova și onorarea Drapelului de Stat al Republicii Moldova.) 2. Luare de cuvînt din partea Fracțiunii parlamentare a Partidului Comuniștilor din Republica Moldova – domnul Vladimir Voronin. 3. Luare de cuvînt din partea Fracțiunii parlamentare a Partidului Liberal Democrat din Moldova – domnul Valeriu Streleț. 4. Luare de cuvînt din partea Fracțiunii parlamentare a Partidului Democrat din Moldova – domnul Dumitru Diacov. 5. Luare de cuvînt din partea Fracțiunii parlamentare a Partidului Liberal – domnul Ion Hadârcă. 6. Dezbateri asupra ordinii de zi și aprobarea ei. 7. Dezbaterea, aprobarea în primă lectură și adoptarea în lectura a doua a proiectului de Lege nr.341 din 15 iulie 2013 pentru ratificarea Convenției Consiliului Europei privind accesul la documentele oficiale. 8. Dezbaterea, aprobarea în primă lectură și adoptarea în lectura a doua a proiectului de Lege nr.343 din 26 iulie 2013 pentru ratificarea Acordului cu privire la colaborarea în domeniul pregătirii specialiștilor subdiviziunilor antiteroriste în instituțiile de învățămînt ale organelor competente ale statelor membre ale Comunității Statelor Independente. 9. Dezbaterea și aprobarea în primă lectură a proiectului Codului transporturilor rutiere. Proiectul nr.267 din 14 iunie 2013. 10. Dezbaterea proiectului de Lege nr.352 din 2 septembrie 2013 cu privire la locuințe. În urma dezbaterilor, s-a luat decizia de a transfera proiectul pînă la pregătirea raportului comisiei. -

OSW COMMENTARY NUMBER 168 1 European Integration (AIE)

Centre for Eastern Studies NUMBER 168 | 22.04.2015 www.osw.waw.pl An appropriated state? Moldova’s uncertain prospects for modernisation Kamil Całus There have been several significant changes on Moldova’s domestic political scene in the wake of the November 2014 parliamentary elections there. Negotiations lasted nearly two months and re- sulted in the formation of a minority coalition composed of two groupings: the Liberal-Democratic Party (PLDM) and the Democratic Party (PDM). New coalition received unofficial support from the Communist Party (PCRM), which had previously been considered an opposition party. Contrary to their initial announcements, PDLM and PDM did not admit the Liberal Party led by Mihai Ghim- pu to power. Moreover, they blocked the nomination for prime minister of the incumbent, Iurie Leancă. Leancă has been perceived by many as an honest politician and a guarantor of reforms. This situation resulted in the political model present in Moldova since 2009 being preserved. In this model the state’s institutions are subordinated to two main oligarch politicians: Vlad Filat (the leader of PLDM) and Vlad Plahotniuc (a billionaire who de facto controls PDM). With control over the state in the hands of Filat and Plahotniuc questions are raised regarding the prospects of Moldova’s real modernisation. It will also have a negative impact on the process of implementation of Moldova’s Association Agreement with the EU and on other key reforms concerning, for example, the judiciary, the financial sector and the process of de-politicisation of the state’s institutions. From both leaders’ perspective, any changes to the current state of affairs would be tantamount to limiting their influence in politics and the economy, which would in turn challenge their business activities. -

Can Moldova Stay on the Road to Europe

MEMO POL I CY CAN MOLDOVA STAY ON THE ROAD TO EUROPE? Stanislav Secrieru SUMMARY In 2013 Russia hit Moldova hard, imposing Moldova is considered a success story of the European sanctions on wine exports and fuelling Union’s Eastern Partnership (EaP) initiative. In the four separatist rumblings in Transnistria and years since a pro-European coalition came to power in 2009, Gagauzia. But 2014 will be much worse. Moldova has become more pluralist and has experienced Russia wants to undermine the one remaining “success story” of the Eastern Partnership robust economic growth. The government has introduced (Georgia being a unique case). It is not clear reforms and has deepened Moldova’s relations with the whether Moldova can rely on Ukraine as a EU, completing a visa-free action plan and initialling an buffer against Russian pressure, which is Association Agreement (AA) with provisions for a Deep and expected to ratchet up sharply after the Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement (DCFTA). At the start Sochi Olympics. Russia wants to change the Moldovan government at the elections due in of 2014, Moldova is one step away from progressing into a November 2014, or possibly even sooner; the more complex, more rewarding phase of relations with the Moldovan government wants to sign the key EU. Implementing the association agenda will spur economic EU agreements before then. growth and will multiply linkages with Moldova’s biggest trading partner, the EU. However, Moldova’s progress down Moldova is most fearful of moves against its estimated 300,000 migrant workers in the European path promises to be one of the main focuses Russia, and of existential escalation of the for intrigue in the region in 2014. -

Summary of Actions in the Framework of the Action Plan for 2013

Appendix 6 Summary of Actions in the framework of the Action Plan for 2013-2015 for Implementation of the Strategy of the IGC TRACECA This document is based on the Reports submitted by Azerbaijan, Armenia, Bulgaria, Georgia, Iran, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Romania, Turkey, Uzbekistan, Ukraine. № Action Short description Obtained results 1 Elaborate five-year Elaboration of national investment In Azerbaijan the implementation of the Governmental concept Programme for infrastructure master plans strategies regarding transport sector development of transport sector is on-going and in accordance with this Programme a based on an adequate methodology for number of laws and normative acts were adopted. infrastructure planning and prioritization The Strategy of transport sector investment is implemented in accordance with the based on the identification of the National Strategy for transport infrastructure planning which is a component of the “bottlenecks” and the use of traffic Governmental concept Programme. forecasts Armenia implements the National Transport Strategy for 2009-2019. One of the priority strategic projects is the infrastructure project for the construction of the North-South Corridor. The programme for development of road infrastructure is composed for 5 years. The allocation programme is updated once in 3 years. In Bulgaria there is applied the Strategy for Development of Transport Infrastructure within the framework of the National Strategy of Integrated Infrastructure Development up to 2015. The Operative Programme of the following programming period 2014-2020 is at the stage of preparation. Annually Georgia works out an action plan for the development of road infrastructure for international main and subsidiary roads. “The Roads Department of Georgia” realized the following construction projects during 2014: - Construction of 32.1 km section Kutaisi bypass-Samtredia of at E60 (JICA) - Construction of 8 km section for Ruisi – Agara E60 Road (WB).