Pediatric Vascular Disorders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Angiokeratoma of the Scrotum (Fordyce Type) Associated with Angiokeratoma of the Oral Cavity

208 Letters to the Editor anti-thyroperoxidas e antibody in addition to, or, less Yamada A. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody- likely, instead of MPO-ANCA cannot be excluded. positive crescentric glomerulonephritis associated with thi- amazole therapy. Nephron 1996; 74: 734–735. Vesiculo-bullous SLE has been reported to respond 6. Cooper D. Antithyroid drugs. N Engl J Med 1984; 311: to dapsone (15). However, in our patient, an early 1353–1362. aggressive treatment with steroid pulse therapy and 7. Yung RL, Richardson BC. Drug-induced lupus. Rheum plasmapheresis was mandatory because of her life- Dis Clin North Am 1994; 20: 61–86. threatening clinical condition. The contributory factors, 8. Hess E. Drug-related lupus. N Engl J Med 1988; 318: 1460–1462. such as an environmental trigger or an immunological 9. Sato-Matsumura KC, Koizumi H, Matsumura T, factor, for the presence of a serious illness in this patient Takahashi T, Adachi K, Ohkawara A. Lupus eryth- remain to be elucidated. The mechanism by which ematosus-like syndrome induced by thiamazole and methimazole induces SLE-like reactions is unclear. propylthiouracil. J Dermatol 1994; 21: 501–507. 10. Wing SS, Fantus IG. Adverse immunologic eVects of antithyroid drugs. Can Med Assoc J 1987; 136: 121–127. 11. Condon C, Phelan M, Lyons JF. Penicillamine-induced REFERENCES type II bullous systemic lupus erythematosus. Br J Dermatol 1997; 136: 474–475. 1. Alarcon-Segovia D. Drug induced lupus syndromes. Mayo 12. Stankus S, Johnson N. Propylthiouracil-induced hyper- Clin Proc 1969; 44: 664–681.2. sensitivity vasculitis presenting as respiratory failure. Chest 2. Cush JJ, Goldings EA. -

The Health-Related Quality of Life of Sarcoma Patients and Survivors In

Cancers 2020, 12 S1 of S7 Supplementary Materials The Health-Related Quality of Life of Sarcoma Patients and Survivors in Germany—Cross-Sectional Results of A Nationwide Observational Study (PROSa) Martin Eichler, Leopold Hentschel, Stephan Richter, Peter Hohenberger, Bernd Kasper, Dimosthenis Andreou, Daniel Pink, Jens Jakob, Susanne Singer, Robert Grützmann, Stephen Fung, Eva Wardelmann, Karin Arndt, Vitali Heidt, Christine Hofbauer, Marius Fried, Verena I. Gaidzik, Karl Verpoort, Marit Ahrens, Jürgen Weitz, Klaus-Dieter Schaser, Martin Bornhäuser, Jochen Schmitt, Markus K. Schuler and the PROSa study group Includes Entities We included sarcomas according to the following WHO classification. - Fletcher CDM, World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer, editors. WHO classification of tumours of soft tissue and bone. 4th ed. Lyon: IARC Press; 2013. 468 p. (World Health Organization classification of tumours). - Kurman RJ, International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organization, editors. WHO classification of tumours of female reproductive organs. 4th ed. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2014. 307 p. (World Health Organization classification of tumours). - Humphrey PA, Moch H, Cubilla AL, Ulbright TM, Reuter VE. The 2016 WHO Classification of Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs—Part B: Prostate and Bladder Tumours. Eur Urol. 2016 Jul;70(1):106–19. - World Health Organization, Swerdlow SH, International Agency for Research on Cancer, editors. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues: [... reflects the views of a working group that convened for an Editorial and Consensus Conference at the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), Lyon, October 25 - 27, 2007]. 4. ed. -

Angiokeratoma of the Scrotum (Fordyce)

Keio Journal of Medicine Vol. 1, No. 1, January, 1952 ANGIOKERATOMA OF THE SCROTUM (FORDYCE) MASAKATSU IZAKI Department of Dermatology, School of Medicine, Keio University Since Fordyce, in 1896, first described a case of angiokeratoma of the scrotum, many authors have reported and discussed about this dermatosis. However the classification and the nomenclature of this skin disease still remain in a state of confusion. Recently I had a chance to see the report of Robinson and Tasker (1946)(14), discussing the nomenclature of this condition, which held my attention considerably. In this paper I wish to report statistical observation concerning the incidences of this dermatosis among Japanese males, and histopathological studies made in 5 cases of this condition. STATISTICALOBSERVATION It must be first pointed out that this study was made along with the statistical study on angioma senile and same persons were examined in both dermatosis (ref. Studies on Senile Changes in the Skin I. Statistical Observation; Journal of the Keio Medical Society Vol. 28, No. 2, p. 59, 1951). The statistics was handled by the small sampling method. Totals of persons examined were 1552 males. Their ages varied from 16 to 84 years, divided into seven groups: i.e. the late teen-agers (16-20), persons of the third decade (21-30), of the fourth decade (31-40), of the fifth decade (41-50), of the sixth decade (51-60), of the seventh decade (61-70) and a group of persons over 71 years of age. The number of persons and the incidence of this condition in each group are summarized briefly in Table 1. -

Traumatic Arteriovenous Malformation of Cheek

AIJOC 10.5005/jp-journals-10003-1138 CASE REPORT Traumatic Arteriovenous Malformation of Cheek: A Case Report and Review of Literature Traumatic Arteriovenous Malformation of Cheek: A Case Report and Review of Literature Vadisha Srinivas Bhat, Rajeshwary Aroor, B Satheesh Kumar Bhandary, Shama Shetty ABSTRACT CASE REPORT Arteriovenous malformations (AVM) are congenital vascular A 31-year-old woman presented with swelling on right anomalies but are usually first noticed in childhood or adulthood. cheek of 6 months duration, which was insidious in onset Head and neck is the most common location for AVM. Extracranial lesions are rare compared to intracranial lesions. and gradually increasing in size. She had a history of The rapid enlargement of the malformation leading to symptoms undergoing dental treatment on the right upper premolar is usually triggered by trauma or hormonal changes of puberty tooth 1 month before the onset of swelling. There was no or pregnancy. Traumatic AVM of the head and neck are very history of any other trauma to the face. There were no rare. Here we report a case of AVM of cheek in an adult woman developed following a dental treatment. The diagnosis was symptoms of nasal disease. On examination, her general confirmed by imaging and was treated surgically after health state was good. There was a swelling measuring angiography and embolization. 3 × 2 cm on the right cheek near the nasolabial grove which Keywords: Arteriovenous malformation, Cheek, Dental was soft, compressible and nontender. The swelling was procedure, Angiography, Embolization. pulsatile (Figs 1 and 2). Nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses How to cite this article: Bhat VS, Aroor R, Bhandary BSK, were within normal limits. -

Vascular Tumors and Malformations of the Orbit

14 Vascular Tumors Kaan Gündüz and Zeynel A. Karcioglu ascular tumors and malformations of the orbit VIII related antigen (v,w,f), CV141 (endothelium, comprise an important group of orbital space- mesothelium, and squamous cells), and VEGFR-3 Voccupying lesions. Reviews indicate that vas- (channels, neovascular endothelium). None of the cell cular lesions account for 6.2 to 12.0% of all histopatho- markers is absolutely specific in its application; a com- logically documented orbital space-occupying lesions bination is recommended in difficult cases. CD31 is (Table 14.1).1–5 There is ultrastructural and immuno- the most often used endothelial cell marker, with pos- histochemical evidence that capillary and cavernous itive membrane staining pattern in over 90% of cap- hemangiomas, lymphangioma, and other vascular le- illary hemangiomas, cavernous hemangiomas, and an- sions are of different nosologic origins, yet in many giosarcomas; CD34 is expressed only in about 50% of patients these entities coexist. Hence, some prefer to endothelial cell tumors. Lymphangioma pattern, on use a single umbrella term, “vascular hamartomatous the other hand, is negative with CD31 and CD34, lesions” to identify these masses, with the qualifica- but, it is positive with VEGFR-3. VEGFR-3 expression tion that, in a given case, one tissue element may pre- is also seen in Kaposi sarcoma and in neovascular dominate.6 For example, an “infantile hemangioma” endothelium. In hemangiopericytomas, the tumor may contain a few caverns or intertwined abnormal cells are typically positive for vimentin and CD34 and blood vessels, but its predominating component is negative for markers of endothelia (factor VIII, CD31, usually capillary hemangioma. -

Angiofibroma of Soft Tissue: a Newly Described Entity; a Case Report and Review of Literature

Open Access Case Report DOI: 10.7759/cureus.6225 Angiofibroma of Soft Tissue: A Newly Described Entity; A Case Report and Review of Literature Zafar Ali 1, 2 , Fatima Anwar 1 1. Histopathology, Shifa International Hospital, Islamabad, PAK 2. Pathology, Shifa College of Medicine, Islamabad, PAK Corresponding author: Zafar Ali, [email protected] Abstract Soft tissue angiofibroma is a relatively recent addition to the ever growing list of benign soft tissue tumors. It usually presents as soft tissue mass in the lower extremities in relation to joints and tendons. The tumor is composed of spindle-shaped fibroblastic cells with arborizing capillaries. We report a case of a 55-year-old female with a lump at the dorsum of left foot. Grossly the tumor was well circumscribed with yellow white cut surface. Microscopically the tumor showed typical features of angiofibroma with myxoid areas near the periphery of the lesion. Prominent vasculature is the integral part of the tumor with numerous small, branching, thin-walled blood vessels, accompanied by medium-sized ectatic vessels. Immunohistochemically the tumor cells are positive for epithelial membrane antigen (EMA). The location of the tumor, lack of cytological atypia, mitosis, and infiltrative margins help differentiate it from a sarcoma. Categories: Pathology Keywords: angiofibroma, ema, soft tissue Introduction Angiofibroma of soft tissue is a recently described entity; it was first described in 2012 by Mariño-Enríquez and Fletcher as a benign fibrovascular tumor that resembles a low grade sarcoma [1]. These tumors typically present in the extremities as a slow growing painless lump. There is a slight female predilection. -

Bajaj A. Vascular and Neurogenic-Cobb Syndrome J Gynecol 2020, 5(1): 000206

Open Access Journal of Gynecology ISSN: 2474-9230 MEDWIN PUBLISHERS Committed to Create Value for Researchers Vascular and Neurogenic-Cobb Syndrome Bajaj A* Mini Review Consultant Histopathologist, A.B.Diagnostics, India Volume 5 Issue 1 *Corresponding author: Anubha Bajaj, Consultant Histopathologist, A.B.Diagnostics, A-1, Received Date: November 09, 2020 Ring Road, Rajouri Garden, New Delhi, 110027, India, Tel: 00911141446785; Email: anubha. Published Date: November 20, 2020 [email protected] DOI: 10.23880/oajg-16000206 Abstract Cobb syndrome is an exceptional, non-inherited, genetic disorder characteristically constituted by vascular anomalies and neurological deficits. Spinal arteriovenous malformations appear in concurrence with cutaneous vascular lesions within the corresponding dermatome. Dermatome specific port wine stain upon the trunk, arteriovenous malformation, angioma, angiokeratoma, angiolipoma, cavernous haemangioma or lymphatic malformation is discerned in accompaniment with (MRI),hyperreflexia, computerized limb paresis, tomography muscular (CT) cramps, scan, plain sensory radiography loss, bladder or angiography. and bowel dysfunction, Cobb syndrome sudden can paraplegia be appropriately or subarachnoid managed haemorrhage. Spinal vascular lesions of Cobb syndrome can be adequately determined with magnetic resonance imaging with sclerotherapy, endovascular embolization, oral corticosteroids or surgical extermination of vascular lesions. Keywords: Cobb Syndrome; Magnetic Resonance Imaging; Computerized Tomography Mini Review birth whereas neurological symptoms emerge around 5 Cobb syndrome is denominated as an extremely exceptional genetic disorder characteristically constituted by years. Incriminated children lack a family history of Cobb syndrome. Of obscure aetiology, Cobb syndrome probably emerges from somatic mutations within the neural crest vascular anomalies and neurological deficits. Cobb syndrome or mesoderm with consequent, antecedent, anatomic withas a anon- cutaneous inherited lesion. -

Benign Hemangiomas

TUMORS OF BLOOD VESSELS CHARLES F. GESCHICKTER, M.D. (From tke Surgical Palkological Laboratory, Department of Surgery, Johns Hopkins Hospital and University) AND LOUISA E. KEASBEY, M.D. (Lancaster Gcaeral Hospital, Lancuster, Pennsylvania) Tumors of the blood vessels are perhaps as common as any form of neoplasm occurring in the human body. The greatest number of these lesions are benign angiomas of the body surfaces, small elevated red areas which remain without symptoms throughout life and are not subjected to treatment. Larger tumors of this type which undergb active growth after birth or which are situated about the face or oral cavity, where they constitute cosmetic defects, are more often the object of surgical removal. The majority of the vascular tumors clinically or pathologically studied fall into this latter group. Benign angiomas of similar pathologic nature occur in all of the internal viscera but are most common in the liver, where they are disclosed usually at autopsy. Angiomas of the bone, muscle, and the central nervous system are of less common occurrence, but, because of the symptoms produced, a higher percentage are available for study. Malignant lesions of the blood vessels are far more rare than was formerly supposed. An occasional angioma may metastasize following trauma or after repeated recurrences, but less than 1per cent of benign angiomas subjected to treatment fall into this group. I Primarily ma- lignant tumors of the vascular system-angiosarcomas-are equally rare. The pathological criteria for these growths have never been ade- quately established, and there is no general agreement as to this par- ticular form of tumor. -

Vascular Malformations, Skeletal Deformities Including Macrodactyly, Embryonic Veins

1.) Give a general classification and nomenclature to think about when evaluating these patients 2.) Share some helpful tips to narrow the differential in a minute or less of interaction 3.) Discuss some helpful imaging recommendations focusing on ultrasound Vascular Anomalies Tumors: Malformations: Hemangiomas: Low flow: Infantile Hemangioma (IH) Capillary malformation (CM) Rapidly involuting congenital hemangioma (RICH) Non-involuting congenital hemangioma (NICH) Venous malformation (VM) Kaposiform Hemangioendothelioma Lymphatic malformation (LM) (KHE) High flow: Arteriovenous malformation (AVM) Tufted Angioma (TA) Combined including syndromic VA. Other rare tumors www.issva.org • 2014 ISSVA classification is now 20 pages long • The key is that the imaging characteristics have not changed • Rapidly growing field • Traditionally, options were always the same – Surgery – Do nothing • With the increase in awareness and research as well as the development of the specialty of vascular anomalies: New Treatment Options Available – Treatment directly linked to diagnosis • Today, we have: – Interventional catheter based therapies – Laser surgery – Ablation technologies: Cryo, RFA, Microwave, etc. – Direct image-guided medications to administer – Infusion medicines – Oral medicines – Surgery- although much less common – Do Nothing- a VERY important alternative • Survey sample of 100 Referred patients – 47% wrong Dx – 35% wrong Tx • 14% wrong Tx with correct Dx • VAC – 14% indeterminate or wrong Dx – only 4% leave with no Tx plan • Important because -

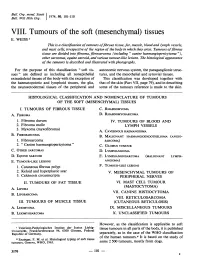

Mesenchymal) Tissues E

Bull. Org. mond. San 11974,) 50, 101-110 Bull. Wid Hith Org.j VIII. Tumours of the soft (mesenchymal) tissues E. WEISS 1 This is a classification oftumours offibrous tissue, fat, muscle, blood and lymph vessels, and mast cells, irrespective of the region of the body in which they arise. Tumours offibrous tissue are divided into fibroma, fibrosarcoma (including " canine haemangiopericytoma "), other sarcomas, equine sarcoid, and various tumour-like lesions. The histological appearance of the tamours is described and illustrated with photographs. For the purpose of this classification " soft tis- autonomic nervous system, the paraganglionic struc- sues" are defined as including all nonepithelial tures, and the mesothelial and synovial tissues. extraskeletal tissues of the body with the exception of This classification was developed together with the haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues, the glia, that of the skin (Part VII, page 79), and in describing the neuroectodermal tissues of the peripheral and some of the tumours reference is made to the skin. HISTOLOGICAL CLASSIFICATION AND NOMENCLATURE OF TUMOURS OF THE SOFT (MESENCHYMAL) TISSUES I. TUMOURS OF FIBROUS TISSUE C. RHABDOMYOMA A. FIBROMA D. RHABDOMYOSARCOMA 1. Fibroma durum IV. TUMOURS OF BLOOD AND 2. Fibroma molle LYMPH VESSELS 3. Myxoma (myxofibroma) A. CAVERNOUS HAEMANGIOMA B. FIBROSARCOMA B. MALIGNANT HAEMANGIOENDOTHELIOMA (ANGIO- 1. Fibrosarcoma SARCOMA) 2. " Canine haemangiopericytoma" C. GLOMUS TUMOUR C. OTHER SARCOMAS D. LYMPHANGIOMA D. EQUINE SARCOID E. LYMPHANGIOSARCOMA (MALIGNANT LYMPH- E. TUMOUR-LIKE LESIONS ANGIOMA) 1. Cutaneous fibrous polyp F. TUMOUR-LIKE LESIONS 2. Keloid and hyperplastic scar V. MESENCHYMAL TUMOURS OF 3. Calcinosis circumscripta PERIPHERAL NERVES II. TUMOURS OF FAT TISSUE VI. -

Orphanet Report Series Rare Diseases Collection

Marche des Maladies Rares – Alliance Maladies Rares Orphanet Report Series Rare Diseases collection DecemberOctober 2013 2009 List of rare diseases and synonyms Listed in alphabetical order www.orpha.net 20102206 Rare diseases listed in alphabetical order ORPHA ORPHA ORPHA Disease name Disease name Disease name Number Number Number 289157 1-alpha-hydroxylase deficiency 309127 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase 228384 5q14.3 microdeletion syndrome deficiency 293948 1p21.3 microdeletion syndrome 314655 5q31.3 microdeletion syndrome 939 3-hydroxyisobutyric aciduria 1606 1p36 deletion syndrome 228415 5q35 microduplication syndrome 2616 3M syndrome 250989 1q21.1 microdeletion syndrome 96125 6p subtelomeric deletion syndrome 2616 3-M syndrome 250994 1q21.1 microduplication syndrome 251046 6p22 microdeletion syndrome 293843 3MC syndrome 250999 1q41q42 microdeletion syndrome 96125 6p25 microdeletion syndrome 6 3-methylcrotonylglycinuria 250999 1q41-q42 microdeletion syndrome 99135 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase 67046 3-methylglutaconic aciduria type 1 deficiency 238769 1q44 microdeletion syndrome 111 3-methylglutaconic aciduria type 2 13 6-pyruvoyl-tetrahydropterin synthase 976 2,8 dihydroxyadenine urolithiasis deficiency 67047 3-methylglutaconic aciduria type 3 869 2A syndrome 75857 6q terminal deletion 67048 3-methylglutaconic aciduria type 4 79154 2-aminoadipic 2-oxoadipic aciduria 171829 6q16 deletion syndrome 66634 3-methylglutaconic aciduria type 5 19 2-hydroxyglutaric acidemia 251056 6q25 microdeletion syndrome 352328 3-methylglutaconic -

8.5 X12.5 Doublelines.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-87409-0 - Modern Soft Tissue Pathology: Tumors and Non-Neoplastic Conditions Edited by Markku Miettinen Index More information Index abdominal ependymoma, 744 mucinous cystadenocarcinoma, 631 adult fibrosarcoma (AF), 364–365, 1026 abdominal extrauterine smooth muscle ovarian adenocarcinoma, 72, 79 adult granulosa cell tumor, 523–524 tumors, 79 pancreatic adenocarcinoma, 846 clinical features, 523 abdominal inflammatory myofibroblastic pulmonary adenocarcinoma, 51 genetics, 524 tumors, 297–298 renal adenocarcinoma, 67 pathology, 523–524 abdominal leiomyoma, 467, 477 serous cystadenocarcinoma, 631 adult rhabdomyoma, 548–549 abdominal leiomyosarcoma. See urinary bladder/urogenital tract clinical features, 548 gastrointestinal stromal tumor adenocarcinoma, 72, 401 differential diagnosis, 549 (GIST) uterine adenocarcinomas, 72 genetics, 549 abdominal perivascular epithelioid cell tumors adenofibroma, 523 pathology, 548–549 (PEComas), 542 adenoid cystic carcinoma, 1035 aggressive angiomyxoma (AAM), 514–518 abdominal wall desmoids, 244 adenomatoid tumor, 811–813 clinical features, 514–516 acquired elastotic hemangioma, 598 adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene, 143 differential diagnosis, 518 acquired tufted angioma, 590 adenosarcoma (mullerian¨ adenosarcoma), 523 genetics, 518 acral arteriovenous tumor, 583 adipocytic lesions (cytology), 1017–1022 pathology, 516 acral myxoinflammatory fibroblastic sarcoma atypical lipomatous tumor/well- aggressive digital papillary adenocarcinoma, (AMIFS), 365–370, 1026 differentiated