Transcript of Your Submissions and Your Presentation, and You Have a Chance to Look at That and Fix up Any Inaccuracies Prior to It Becoming Public

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vegetation and Flora of Booti Booti National Park and Yahoo Nature Reserve, Lower North Coast of New South Wales

645 Vegetation and flora of Booti Booti National Park and Yahoo Nature Reserve, lower North Coast of New South Wales. S.J. Griffith, R. Wilson and K. Maryott-Brown Griffith, S.J.1, Wilson, R.2 and Maryott-Brown, K.3 (1Division of Botany, School of Rural Science and Natural Resources, University of New England, Armidale NSW 2351; 216 Bourne Gardens, Bourne Street, Cook ACT 2614; 3Paynes Lane, Upper Lansdowne NSW 2430) 2000. Vegetation and flora of Booti Booti National Park and Yahoo Nature Reserve, lower North Coast of New South Wales. Cunninghamia 6(3): 645–715. The vegetation of Booti Booti National Park and Yahoo Nature Reserve on the lower North Coast of New South Wales has been classified and mapped from aerial photography at a scale of 1: 25 000. The plant communities so identified are described in terms of their composition and distribution within Booti Booti NP and Yahoo NR. The plant communities are also discussed in terms of their distribution elsewhere in south-eastern Australia, with particular emphasis given to the NSW North Coast where compatible vegetation mapping has been undertaken in many additional areas. Floristic relationships are also examined by numerical analysis of full-floristics and foliage cover data for 48 sites. A comprehensive list of vascular plant taxa is presented, and significant taxa are discussed. Management issues relating to the vegetation of the reserves are outlined. Introduction The study area Booti Booti National Park (1586 ha) and Yahoo Nature Reserve (48 ha) are situated on the lower North Coast of New South Wales (32°15'S 152°32'E), immediately south of Forster in the Great Lakes local government area (Fig. -

Biodiversity of Michigan's Great Lakes Islands

FILE COPY DO NOT REMOVE Biodiversity of Michigan’s Great Lakes Islands Knowledge, Threats and Protection Judith D. Soule Conservation Research Biologist April 5, 1993 Report for: Land and Water Management Division (CZM Contract 14C-309-3) Prepared by: Michigan Natural Features Inventory Stevens T. Mason Building P.O. Box 30028 Lansing, MI 48909 (517) 3734552 1993-10 F A report of the Michigan Department of Natural Resources pursuant to National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Award No. 309-3 BIODWERSITY OF MICHIGAN’S GREAT LAKES ISLANDS Knowledge, Threats and Protection by Judith D. Soule Conservation Research Biologist Prepared by Michigan Natural Features Inventory Fifth floor, Mason Building P.O. Box 30023 Lansing, Michigan 48909 April 5, 1993 for Michigan Department of Natural Resources Land and Water Management Division Coastal Zone Management Program Contract # 14C-309-3 CL] = CD C] t2 CL] C] CL] CD = C = CZJ C] C] C] C] C] C] .TABLE Of CONThNTS TABLE OF CONTENTS I EXECUTIVE SUMMARY iii INTRODUCTION 1 HISTORY AND PHYSICAL RESOURCES 4 Geology and post-glacial history 4 Size, isolation, and climate 6 Human history 7 BIODWERSITY OF THE ISLANDS 8 Rare animals 8 Waterfowl values 8 Other birds and fish 9 Unique plants 10 Shoreline natural communities 10 Threatened, endangered, and exemplary natural features 10 OVERVIEW OF RESEARCH ON MICHIGAN’S GREAT LAKES ISLANDS 13 Island research values 13 Examples of biological research on islands 13 Moose 13 Wolves 14 Deer 14 Colonial nesting waterbirds 14 Island biogeography studies 15 Predator-prey -

Trends in Numbers of Piscivorous Birds in Western Port and West Corner Inlet, Victoria, 1987–2012 P

Trends in Numbers of Piscivorous Birds in Western Port and West Corner Inlet, Victoria, 1987–2012 P. W. Menkhorst, R. H. Loyn, C. Liu, B. Hansen, M. Mackay and P. Dann February 2015 Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Unpublished Client Report for Melbourne Water Trends in numbers of piscivorous birds in Western Port and West Corner Inlet, Victoria, 1987–2012 Peter W. Menkhorst 1, Richard H. Loyn 1,2 , Canran Liu 1, Birgita Hansen 1,3 , Moragh Mackay 4 and Peter Dann 5 1Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research 123 Brown Street, Heidelberg, Victoria 3084 2Current address: Eco Insights Pty Ltd 4 Roderick Close, Viewbank, Victoria 3084 3Current address: Collaborative Research Network, Federation University (Mt Helen) PO Box 663, Ballarat, Victoria 3353 4Riverbend Ecological Services 2620 Bass Highway, Bass, Victoria 3991 5Research Department, Phillip Island Nature Parks P0 Box 97, Cowes, Victoria 3991 February 2015 in partnership with Melbourne Water Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning Heidelberg, Victoria Report produced by: Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning PO Box 137 Heidelberg, Victoria 3084 Phone (03) 9450 8600 Website: www.delwp.vic.gov.au Citation: Menkhorst, P.W., Loyn, R.H., Liu, C., Hansen, B., McKay, M. and Dann, P. (2015). Trends in numbers of piscivorous birds in Western Port and West Corner Inlet, Victoria, 1987–2012. Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Unpublished Client Report for Melbourne Water. Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, Heidelberg, Victoria. Front cover photo: Crested Terns feed on small fish such as Southern Anchovy Engraulis australis (Photo: Peter Menkhorst). -

Download Full Article 4.7MB .Pdf File

. https://doi.org/10.24199/j.mmv.1979.40.04 31 July 1979 VERTEBRATE FAUNA OF SOUTH GIPPSLAND, VICTORIA By K. C. Norris, A. M. Gilmore and P. W. Menkhorst Fisheries and Wildlife Division, Ministry for Conservation, Arthur Ryiah Institute for Environmental Research, 123 Brown Street, Heidelberg, Victoria 3084 Abstract The South Gippsland area of eastern Victoria is the most southerly part of the Australian mainland and is contained within the Bassian zoogeographic subregion. The survey area contains most Bassian environments, including ranges, river flats, swamps, coastal plains, mountainous promontories and continental islands. The area was settled in the mid 180()s and much of the native vegetation was cleared for farming. The status (both present and historical) of 375 vertebrate taxa, 50 mammals, 285 birds, 25 reptiles and 15 amphibians is discussed in terms of distribution, habitat and abundance. As a result of European settlement, 4 mammal species are now extinct and several bird species are extinct or rare. Wildlife populations in the area now appear relatively stable and are catered for by six National Parks and Wildlife Reserves. Introduction TOPOGRAPHY AND PHYSIOGRAPHY {see Hills 1967; and Central Planning Authority 1968) Surveys of wildlife are being conducted by The north and central portions of the area the Fisheries and Wildlife Division of the are dominated by the South Gippsland High- Ministry for Conservation as part of the Land lands (Strzelecki Range) which is an eroded, Conservation Council's review of the use of rounded range of uplifted Mesozoic sand- Crown Land in Victoria. stones and mudstones rising to 730 m. -

Literature Review: Responses of Koalas to Translocation

Literature review: responses of Koalas to translocation P. Menkhorst February 2017 Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Technical Report Series No. 279 Literature review: responses of Koalas to translocation Peter Menkhorst Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research 123 Brown Street, Heidelberg, Victoria 3084 February 2017 Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning Heidelberg, Victoria Report produced by: Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning PO Box 137 Heidelberg, Victoria 3084 Phone (03) 9450 8600 Website: www.delwp.vic.gov.au Citation: Menkhorst, P. 2017. Literature review: responses of Koalas to translocation. Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Technical Report Series Number 279. Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, Heidelberg, Victoria. Front cover photo: Releasing French Island Koalas from the transport crate, Tallarook State Forest, 8 November 2016. Photo, author. © The State of Victoria Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning 2015 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. You are free to re-use the work under that licence, on the condition that you credit the State of Victoria as author. The licence does not apply to any images, photographs or branding, including the Victorian Coat of Arms, the Victorian Government logo, the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning logo and the Arthur Rylah Institute logo. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en ISBN 978-1-76047-569-7 (Print) 978-1-76047-570-3 (pdf/online) Accessibility If you would like to receive this publication in an alternative format, please telephone the DELWP Customer Service Centre on 136 186, email [email protected] or contact us via the National Relay Service on 133 677 or www.relayservice.com.au . -

Melbourne Branch February Roar 110 Only

Sambar’s Roar The bi-monthly newsletter of the Melbourne Branch of the Australian Deer Association Inc. ABN 44 060 933 897. PO. Box 258, Bulleen. Melbourne. Victoria. Australia. 3105 February 2021 Volume 41 Issue 1 Melbourne Branch February Roar 110 Only We are back! As we can only have 110 attendees, invitations have been sent out, “first in best dressed!” Our next Branch meeting is at the Austrian Club on 11 Feb, starting at 7.30pm and at 8.00pm a presentation from the GMA. CEO Graeme Ford and Zach Powell from GMA will talk to us about: ➢ State of play of GMA ➢ New Licensing System ➢ Government commitments delivered under SHAP and opportunities to feed into the new SHAP 2.0 ➢ Process for upcoming regulator review. First Prize in our raffle is the Austealth Native Camouflage 44L Stealth Backpack. RRP $220 Austealth Native Camouflage 44L Stealth Backpack $220.00 • 44L • Knit Fabric with PVC Coating • 400gsm • Gun Holder • Rain Cover -Blaze Orange • Provision for a Water Bladder • Padded waist belt with pockets • Water bottle pockets left and right • Webbing Loops on top and bottom • Inside pack organiser • Shock compression cord • Hanging hook • Height of Bag 66cm Second Prize: 1 boning knife & 1 skinning knife set Supplied by My Slice of Life. Third prize: is a 20kg bag of dog food from Addiction Outdoors Please support or sponsors. We will also be awarding the 2019 Trophy Competition awards under various categories of best deer etc. Due to the disruption of last year, the 2020 trophy awards will be given out at the April meeting now. -

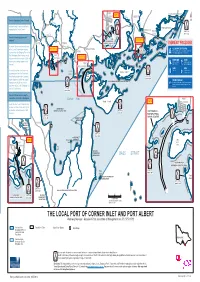

Corner Inlet & Port Albert

PROCTORS WORANGA TOORA NORTH BINGINWARRI BALLOONG STONY CREEK WOORARRA WEST PORT INSET C McLOUGHLINS BEACH ALBERT Albert ALBERTON Vessels departing Lewis Channel Agnes N Franklin Tara must give way to any vessel that is R St Margaret Island navigating the Toora Channel TARRAVILLE MANNS 2200m00m ofof tthehe R R BEACH wwatersaters eedgedge SOUTH Vessels intending toCk proceed SEE INSET C outward NNOORAMUNGAOORAMUNGA River FOSTERFOSTER TOORA HIGHWAY MARINEMARINE & COASTALCOASTAL PARKPARK G A vessel 10m or more in length and IPPSLAND in the Lewis Channel proceeding SEE INSET A WELSHPOOL PORTPORT AGNES ALBERTALBERT outward fromFish the Shipping Pier or the Port Welshpool Boat Harbour, must PPORTORT SEE INSET B FFRANKLINRANKLIN not proceed FISH whilst a vessel of 25m or more is proceeding inward in that CREEK channel. PPORTORT WELSHPOOLWELSHPOOL A vessel less than 10m length and BARRY Sunday Island departing from the Port Welshpool BEACH Little Boat Harbour, proceeding outward Snake 2200m00m ooff tthehe must not proceed whilst an inward Island waterswaters edgeedge NOORAMUNGA MARINE & COASTAL PARK bound vessel of 25m or more is FOSTER T oo underway between the Shipping Pier ra and the Boat Harbour 2200m00m ooff tthehe C waterswaters edgeedge h an ne Vessels 25m or more in length l inward bound for Port WelshpoolMEENIYAN Corner Inlet PORT Snake Island INSET B WELSHPOOL must not enter Lewis Channel whilst l a vessel of 25m or more in length is CORNER INLET proceeding outward bound in that MARINE & COASTAL PARK 2200m00m ooff tthehe PORT FRANKLIN -

Distributions of Fallow Deer, Red Deer, Hog Deer and Chital Deer in Victoria

Distributions of Fallow Deer, Red Deer, Hog Deer and Chital Deer in Victoria David M. Forsyth, Kasey Stamation and Luke Woodford Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research 123 Brown Street, Heidelberg, Victoria 3084 April 2016 Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning Heidelberg, Victoria ii Distributions of Fallow Deer, Red Deer, Hog Deer and Chital Deer in Victoria Report produced by: Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning PO Box 137 Heidelberg, Victoria 3084 Phone (03) 9450 8600 Website: www.delwp.vic.gov.au/ari Citation: Forsyth, D.M., Stamation, K. and Woodford, L. (2016). Distributions of Fallow Deer, Red Deer, Hog Deer and Chital Deer in Victoria. Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Unpublished Client Report for the Biosecurity Branch, Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport and Resources. Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research, Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, Heidelberg, Victoria. Front cover photo: Adult female Red Deer and calf in a pine plantation, Gippsland, February 2012 (photo: Rohan Bilney). © The State of Victoria Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning 2016 Edited by Organic Editing Disclaimer This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims -

Distributions of Sambar Deer, Rusa Deer and Sika Deer in Victoria

Distributions of Sambar Deer, Rusa Deer and Sika Deer in Victoria David M. Forsyth, Kasey Stamation and Luke Woodford Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning 123 Brown Street, Heidelberg, Victoria 3084 July 2015 Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning Heidelberg, Victoria Distributions of Sambar Deer, Rusa Deer and Sika Deer in Victoria Contents Acknowledgements 1 Summary 2 Background 2 Objective 2 Methodology 2 Results and Conclusions 2 Recommendations 3 1 Introduction 4 2 Objective 4 3 Methodology 5 3.1 Data sources 5 3.2 Data storage and visualisation 6 4 Results 6 4.1 Sambar Deer 6 4.2 Rusa Deer 11 4.3 Sika Deer 13 5 Discussion 13 5.1 Sambar Deer 13 5.2 Rusa Deer 15 5.3 Sika Deer 15 6 Conclusions 16 7 Recommendations 16 References 17 Appendix 20 iii Distributions of Sambar Deer, Rusa Deer and Sika Deer in Victoria Acknowledgements This work was commissioned by the Biosecurity Division, Department of Environment and Primary Industries (now Biosecurity Branch, Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport and Resources). We thank all the interviewees (listed in the Appendix), who kindly shared their knowledge about the distributions of deer in Victoria, New South Wales and South Australia. Mike Braysher (University of Canberra) kindly provided background information about the importation of Sika Deer into Australia. We thank Andrew Woolnough (Biosecurity Branch, Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport and Resources) for reviewing a draft of this report, and Jeanette Birtles (Organic Editing) for editorial services. -

Segment 7 Map Book

LEVY LEVY Dunnellon Inglis Yankeetown MARION ´ MM aa pp 11 -- AA Crystal River MM aa pp 11 -- BB CITRUS Inverness MM aa pp 22 -- AA FF ll oo rr ii dd aa CC ii rr cc uu mm nn aa vv ii gg aa tt ii oo nn aa ll SS aa ll tt ww aa tt ee rr PP aa dd dd ll ii nn gg TT rr aa ii ll MM aa pp 22 -- BB SS ee gg mm ee nn tt 77 MM aa pp 33 -- AA NN aa tt uu rr ee CC oo aa ss tt SUMTER MM aa pp 33 -- BB op Drinking Water HERNANDO t[ Camping Weeki Wachee Kayak Launch MM aa pp 44 -- AA Shower Facility I* Restroom MM aa pp 44 -- BB I9 Restaurant ²· Grocery Store e! Point of Interest MM aa pp 55 -- AA l Hotel / Motel PASCO Port Richey MM aa pp 55 -- BB New Port Richey Tarpon Springs Tarpon Springs PINELLAS HILLSBOROUGH Disclaimer: This guide is intended as an aid to navigation only. A Gobal Positioning System (GPS) unit is Tarpon Springs required, and persons are encouraged to supplement these maps with NOAA charts or other maps. 3 Segment 7: Nature Co3ast Richardson Creek Map 1 A 3 Withlacoochee River Everett Island 3 Burtine Island Cross Creek Deadman Key Captain Joe Island 3 Lutrell Island3 A Spoil Island Campsite 3 Drum Island 3 3 Little Rocky Creek 3 6 Demory Gap Doghead Gap 3 Rocky CreekLong Point Rocky Cove 12 6 12 Jetty Crossover 6 N 28.9435 I W -82.7762 Double Barrel Creek 3 Tony Creek 3 Tin Pan Gap Salt Creek 6 Crystal River Entrance 3 N 28.9226 I W -82.6963 Crystal River Preserve State Park 6 Black Point Cedar Creek 6 Crab Creek 6 Crystal River Rocky Island Crystal Bay Gomez Creek Shell Island South Pass Wash Island N: 28.9764 I W: -82.7808 12 -

Corner Inlet Ramsar Site

Corner Inlet Ramsar site Ecological Character Description June 2011 Chapters 1-2 Other chapters can be downloaded from: www.environment.gov.au/water/publications/environmental/wetlands/13-ecd.html INTRODUCTION 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background The Corner Inlet Ramsar site, which covers 67 186 hectares, is located approximately 200 kilometres south-east of Melbourne and is the most southerly marine embayment and intertidal system of mainland Australia (Figures 1-1, 1-2 and 1-3). Corner Inlet is one of 64 wetland areas in Australia that have been listed as a Wetland of International Importance under the Convention on Wetlands of International Importance especially as Waterfowl Habitat or, as it is more commonly referred to, the Ramsar Convention (the Convention). Corner Inlet was listed as a Ramsar site under the Convention in December 1982 in recognition of its outstanding coastal wetland values and features. The Convention sets out the need for contracting parties to conserve and promote wise use of wetland resources. In this context, an assessment of ecological character of each listed wetland is a key concept under the Ramsar Convention. Under Resolution IX.1 Annex A: 2005, the ecological character of a wetland is defined as: The combination of the ecosystem components, processes and benefits/services that characterise the wetland at a given point in time. The definition indicates that ecological character has a temporal component, generally using the date of listing under the Convention as the point for measuring ecological change over time. As such, the description of ecological character should identify a wetland’s key elements and provide an assessment point for the monitoring and evaluation of the site as well as guide policy and management, acknowledging the inherent dynamic nature of wetland systems over time. -

Port Phillip Bay (Western Shoreline) and Bellarine Peninsula Ramsar Site Boundary Description

Port Phillip Bay (Western Shoreline) and Bellarine Peninsula Ramsar Site Boundary Description Technical Report Published by the Victorian Government Department of Environment and Primary Industries Melbourne, December 2013 © The State of Victoria Department of Environment and Primary Industries Melbourne 2013 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968 . Authorised by the Victorian Government, 8 Nicholson Street, East Melbourne. ISBN 978-1-74242-098-1(online) For more information contact the DEPI Customer Service Centre 136 186 Citation: DEPI (2013) Port Phillip Bay (Western Shoreline) and Bellarine Peninsula Ramsar Site Boundary Description Technical Report. Department of Environment and Primary Industries, East Melbourne, Victoria. Disclaimer This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence which may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. Accessibility If you would like to receive this publication in an accessible format, such as large print or audio, please telephone 136 186, or email [email protected] Deaf, hearing impaired or speech impaired? Call us via the National Relay Service on 133 677 or visit www.relayservice.com.au This document is also available in PDF format on the internet at www.depi.vic.gov.au Cover photo: Yvette Baker July 2010. Contents Introduction 1 Methodology of RAMSAR 100 GIS layer boundary realignment 2 Location 3 Written description of the Port Phillip Bay (Western Shoreline) and Bellarine Peninsula Ramsar Site boundary 4 Section 1: Coastline from Skeleton Creek to Point Cooke 4 Section 2: Block from Werribee River to Avalon Airfield.