Treatment of Acute Neurolepticinduced Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table 2. 2012 AGS Beers Criteria for Potentially

Table 2. 2012 AGS Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults Strength of Organ System/ Recommendat Quality of Recomm Therapeutic Category/Drug(s) Rationale ion Evidence endation References Anticholinergics (excludes TCAs) First-generation antihistamines Highly anticholinergic; Avoid Hydroxyzin Strong Agostini 2001 (as single agent or as part of clearance reduced with e and Boustani 2007 combination products) advanced age, and promethazi Guaiana 2010 Brompheniramine tolerance develops ne: high; Han 2001 Carbinoxamine when used as hypnotic; All others: Rudolph 2008 Chlorpheniramine increased risk of moderate Clemastine confusion, dry mouth, Cyproheptadine constipation, and other Dexbrompheniramine anticholinergic Dexchlorpheniramine effects/toxicity. Diphenhydramine (oral) Doxylamine Use of diphenhydramine in Hydroxyzine special situations such Promethazine as acute treatment of Triprolidine severe allergic reaction may be appropriate. Antiparkinson agents Not recommended for Avoid Moderate Strong Rudolph 2008 Benztropine (oral) prevention of Trihexyphenidyl extrapyramidal symptoms with antipsychotics; more effective agents available for treatment of Parkinson disease. Antispasmodics Highly anticholinergic, Avoid Moderate Strong Lechevallier- Belladonna alkaloids uncertain except in Michel 2005 Clidinium-chlordiazepoxide effectiveness. short-term Rudolph 2008 Dicyclomine palliative Hyoscyamine care to Propantheline decrease Scopolamine oral secretions. Antithrombotics Dipyridamole, oral short-acting* May -

Blockade of Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptors Facilitates Motivated Behaviour and Rescues a Model of Antipsychotic- Induced Amotivation

www.nature.com/npp ARTICLE Blockade of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors facilitates motivated behaviour and rescues a model of antipsychotic- induced amotivation Jonathan M. Hailwood 1, Christopher J. Heath2, Benjamin U. Phillips1, Trevor W. Robbins1, Lisa M. Saksida3,4 and Timothy J. Bussey1,3,4 Disruptions to motivated behaviour are a highly prevalent and severe symptom in a number of neuropsychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders. Current treatment options for these disorders have little or no effect upon motivational impairments. We assessed the contribution of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors to motivated behaviour in mice, as a novel pharmacological target for motivational impairments. Touchscreen progressive ratio (PR) performance was facilitated by the nonselective muscarinic receptor antagonist scopolamine as well as the more subtype-selective antagonists biperiden (M1) and tropicamide (M4). However, scopolamine and tropicamide also produced increases in non-specific activity levels, whereas biperiden did not. A series of control tests suggests the effects of the mAChR antagonists were sensitive to changes in reward value and not driven by changes in satiety, motor fatigue, appetite or perseveration. Subsequently, a sub-effective dose of biperiden was able to facilitate the effects of amphetamine upon PR performance, suggesting an ability to enhance dopaminergic function. Both biperiden and scopolamine were also able to reverse a haloperidol-induced deficit in PR performance, however only biperiden was able to rescue the deficit in effort-related choice (ERC) performance. Taken together, these data suggest that the M1 mAChR may be a novel target for the pharmacological enhancement of effort exertion and consequent rescue of motivational impairments. Conversely, M4 receptors may inadvertently modulate effort exertion through regulation of general locomotor activity levels. -

The Influence of a Muscarinic M1 Receptor Antagonist on Brain Choline Levels in Patients with a Psychotic Disorder and Healthy Controls

MHENS School for Mental Health and Neuroscience The influence of a muscarinic M1 receptor antagonist on brain choline levels in patients with a psychotic disorder and healthy controls. W.A.M. VingerhoetsA,B, G. BakkerA,B, O. BloemenA,C, M. CaanD, J. BooijB, T.A.M.J. van AmelsvoortA. A Department of Psychiatry & Psychology, Maastricht University, Maastricht, The Netherlands.. B Department of Nuclear Medicine, Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. C GGZ Centraal, Center for Mental Health Care, Hilversum, The Netherlands D Department of Radiology, Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands Background • The majority of the patients with a psychotic disorder report cognitive impairments in addition to positive and negative symptoms. • It is well known that the neurotransmitter acetylcholine plays an important role in cognition. • A post-mortem study of chronic schizophrenia patients demonstrated a reduction of up to 75% in the number of the acetylcholine muscarinic M1 receptors (1). • Research has shown that muscarinic cholinergic receptors play a major role in cognitive processes. Objective • To investigate in-vivo whether there are differences in baseline choline levels in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and striatum between recent onset medication-free patients with a psychotic disorder and healthy control subjects. • To investigate in-vivo the influence of a muscarinic antagonist on choline levels in the ACC and striatum in recent onset medication-free patients with Figure 2. Example of a striatal spectrum. a psychotic disorder and healthy control subjects. Results Methods • No significant differences were found in baseline choline levels between the two groups in both the striatum (p=0.336) and the ACC (p=0.479). -

A Comparison of Scopolamine and Biperiden As a Rodent Model for Cholinergic Cognitive Impairment

Psychopharmacology (2011) 215:549–566 DOI 10.1007/s00213-011-2171-1 ORIGINAL INVESTIGATION A comparison of scopolamine and biperiden as a rodent model for cholinergic cognitive impairment Inge Klinkenberg & Arjan Blokland Received: 30 June 2010 /Accepted: 9 January 2011 /Published online: 19 February 2011 # The Author(s) 2011. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract Keywords Sensorimotor . Motivation . Attention . Rationale The nonselective muscarinic antagonist scopol- Memory. Animal model . Fixed ratio . Progressive ratio . amine hydrobromide (SCOP) is employed as the gold Delayed nonmatching to position . Muscarinic . standard for inducing memory impairments in healthy Acetylcholine humans and animals. However, its use remains controversial due to the wide spectrum of behavioral effects of this drug. Objective The present study investigated whether biperiden Introduction (BIP), a muscarinic m1 receptor antagonist, is to be preferred over SCOP as a pharmacological model for The muscarinic antagonist scopolamine hydrobromide cholinergic memory deficits in rats. This was done by (SCOP) is used as the gold standard for inducing deficits comparing the effects of SCOP and BIP using a battery of in human and animal models of memory dysfunction. operant tasks: fixed ratio (FR5) and progressive ratio Justification for this purpose has been provided by the (PR10) schedules of reinforcement, an attention paradigm cholinergic hypothesis of geriatric memory dysfunction and delayed nonmatching to position task. proposed in the early 1980s by Bartus et al. (1982). The Results SCOP induced diffuse behavioral disruption, which SCOP model is still used extensively for preclinical testing included sensorimotor responding (FR5, 0.3 and 1 mg/kg), of new substances designed to treat cognitive impairment food motivation (PR10, 1 mg/kg), attention (0.3 mg/kg, (e.g., Barak and Weiner 2009; Buccafusco et al. -

In Vivo Olanzapine Occupancy of Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptors in Patients with Schizophrenia Thomas J

In Vivo Olanzapine Occupancy of Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptors in Patients with Schizophrenia Thomas J. Raedler, M.D., Michael B. Knable, D.O., Douglas W. Jones, Ph.D., Todd Lafargue, M.D., Richard A. Urbina, B.A., Michael F. Egan, M.D., David Pickar, M.D. , and Daniel R. Weinberger, M.D. Olanzapine is an atypical antipsychotic with potent than low-dose in the same regions. Muscarinic occupancy ϭ antimuscarinic properties in vitro (Ki 2–25 nM). We by olanzapine ranged from 13% to 57% at 5 mg/dy and studied in vivo muscarinic receptor occupancy by 26% to 79% at 20 mg/dy with an anatomical pattern olanzapine at both low dose (5 mg/dy) and high dose (20 indicating M2 subtype selectivity. The [I-123]IQNB data mg/dy) in several regions of cortex, striatum, thalamus and indicate that olanzapine is a potent and subtype-selective pons by analyzing [I-123]IQNB SPECT images of seven muscarinic antagonist in vivo, perhaps explaining its low schizophrenia patients. Both low-dose and high-dose extrapyramidal side effect profile and low incidence of olanzapine studies revealed significantly lower anticholinergic side effects. [Neuropsychopharmacology [I-123]IQNB binding than that of drug-free schizophrenia 23:56–68, 2000] Published by Elsevier Science Inc. on patients (N ϭ 12) in all regions except striatum. behalf of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology [I-123]IQNB binding was significantly lower at high-dose KEY WORDS: Muscarinic receptor; Olanzapine; IQNB; cologically (Watling et al. 1995) and correspond to SPECT; Schizophrenia; Antipsychotic genes (respectively, m1–m5) that have been cloned (Bonner et al. -

Hypersalivation in Children and Adults

Pharmacological Management of Hypersalivation in Children and Adults Scope: Adult patients with Parkinson’s disease, children with neurodisability, cerebral palsy, long-term ventilation with drooling, and drug-induced hypersalivation. ASSESSMENT OF SEVERITY/RESPONSE TO TREATMENT: Severity of drooling can be assessed subjectively via discussion with patients and their carers/parents and by observation. Amount of drooling can be quantified by measuring the number of bibs required per day and this can also be graded using the Thomas-Stonell and Greenberg scale: • 1 = Dry (no drooling) • 2 = Mild (moist lips) • 3 = Moderate (wet lips and chin) • 4 = Severe (damp clothing) CONSIDERATIONS FOR PRESCRIBING/TITRATION No evidence to support the use of one particular treatment over another. Drug choice is to be determined by individual patient factors. When prescribing/titrating antimuscarinic drugs to treat hypersalivation always take account of: • Coexisting conditions (for example, history of urinary retention, constipation, glaucoma, dental issues, reflux etc.) • Use of other existing medication affecting the total antimuscarinic burden • Risk of adverse effects Titrate dose upward until the desired level of dryness, side effects or maximum dose reached. Take into account the preferences of the patients and their carers/ parents, and the age range and indication covered by the marketing authorisations (see individual summaries of product characteristics, BNF or BNFc for full prescribing information). FIRST LINE DRUG TREATMENT OPTIONS FOR ADULTS -

Mnemonic and Behavioral Effects of Biperiden, an M1-Selective Antagonist, in the Rat

Psychopharmacology https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-018-4899-3 ORIGINAL INVESTIGATION Mnemonic and behavioral effects of biperiden, an M1-selective antagonist, in the rat Anna Popelíková1 & Štěpán Bahník2 & Veronika Lobellová1 & Jan Svoboda1 & Aleš Stuchlík1 Received: 6 October 2017 /Accepted: 9 April 2018 # Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2018 Abstract Rationale There is a persistent pressing need for valid animal models of cognitive and mnemonic disruptions (such as seen in Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias) usable for preclinical research. Objectives We have set out to test the validity of administration of biperiden, an M1-acetylcholine receptor antagonist with central selectivity, as a potential tool for generating a fast screening model of cognitive impairment, in outbred Wistar rats. Methods We used several variants of the Morris water maze task: (1) reversal learning, to assess cognitive flexibility, with probe trials testing memory retention; (2) delayed matching to position (DMP), to evaluate working memory; and (3) Bcounter-balanced acquisition,^ to test for possible anomalies in acquisition learning. We also included a visible platform paradigm to reveal possible sensorimotor and motivational deficits. Results A significant effect of biperiden on memory acquisition and retention was found in the counter-balanced acquisition and probe trials of the counter-balanced acquisition and reversal tasks. Strikingly, a less pronounced deficit was observed in the DMP. No effects were revealed in the reversal learning task. Conclusions Based on our results, we do not recommend biperiden as a reliable tool for modeling cognitive impairment. Keywords Anticholinergics . Muscarinic receptors . Learning . Memory . Morris water maze . Rat Abbreviations DMSO Dimethyl-sulfoxide Ach Acetylcholine GABA Gamma-amino-butyric acid AChR Acetylcholine receptors GPCRs G-Protein coupled receptors AD Alzheimer’sdisease i.p. -

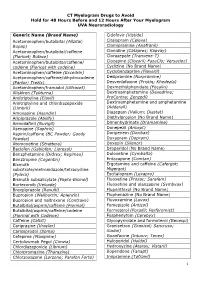

CT Myelogram Drugs to Avoid Hold for 48 Hours Before and 12 Hours After Your Myelogram UVA Neuroradiology

CT Myelogram Drugs to Avoid Hold for 48 Hours Before and 12 Hours After Your Myelogram UVA Neuroradiology Generic Name (Brand Name) Cidofovir (Vistide) Acetaminophen/butalbital (Allzital; Citalopram (Celexa) Bupap) Clomipramine (Anafranil) Acetaminophen/butalbital/caffeine Clonidine (Catapres; Kapvay) (Fioricet; Butace) Clorazepate (Tranxene-T) Acetaminophen/butalbital/caffeine/ Clozapine (Clozaril; FazaClo; Versacloz) codeine (Fioricet with codeine) Cyclizine (No Brand Name) Acetaminophen/caffeine (Excedrin) Cyclobenzaprine (Flexeril) Acetaminophen/caffeine/dihydrocodeine Desipramine (Norpramine) (Panlor; Trezix) Desvenlafaxine (Pristiq; Khedezla) Acetaminophen/tramadol (Ultracet) Dexmethylphenidate (Focalin) Aliskiren (Tekturna) Dextroamphetamine (Dexedrine; Amitriptyline (Elavil) ProCentra; Zenzedi) Amitriptyline and chlordiazepoxide Dextroamphetamine and amphetamine (Limbril) (Adderall) Amoxapine (Asendin) Diazepam (Valium; Diastat) Aripiprazole (Abilify) Diethylpropion (No Brand Name) Armodafinil (Nuvigil) Dimenhydrinate (Dramamine) Asenapine (Saphris) Donepezil (Aricept) Aspirin/caffeine (BC Powder; Goody Doripenem (Doribax) Powder) Doxapram (Dopram) Atomoxetine (Strattera) Doxepin (Silenor) Baclofen (Gablofen; Lioresal) Droperidol (No Brand Name) Benzphetamine (Didrex; Regimex) Duloxetine (Cymbalta) Benztropine (Cogentin) Entacapone (Comtan) Bismuth Ergotamine and caffeine (Cafergot; subcitrate/metronidazole/tetracycline Migergot) (Pylera) Escitalopram (Lexapro) Bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol) Fluoxetine (Prozac; Sarafem) -

Akineton 2 Mg SUMMARY of PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS

SUMMARY OF PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS Pa ge 1 von 8 Akineton 2 mg SUMMARY OF PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS 1. NAME OF THE MEDICINAL PRODUCT Akineton® 2 mg - tablets 2. QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION Active substance: Biperiden Hydrochloride. 1 tablet contains 2 mg Biperiden Hydrochloride equivalent to 1.8 mg Biperiden. Excipient with known effect: Lactose monohydrate 38 mg. For the full list of excipients, see section 6.1. 3. PHARMACEUTICAL FORM White, biplanar tablet, cross-scored on one side. The tablet can be divided into equal doses. 4. CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1 Therapeutic indications - All forms of parkinsonism, - Drug-induced extrapyramidal symptoms excito-motor phenomena, parkinsonoid, akinesia, rigidity, akathisia, acute dystonia. 4.2 Posology and method of administration Biperiden has to be dosed individually. Treatment should begin with the lowest dose and then be increased to the most favourable dose for the patient. Posology Adults Parkinson syndrome Initially 2 times ½ tablet (2 mg Biperiden hydrochloride/day) distributed over the day. The dose can be increased daily by 2 mg. As maintenance dose, 3–4 times daily ½–2 tablets (corresponding to 3– 16 mg/day) are administered. The maximum daily dose amounts to 16 mg Biperiden hydrochloride (corresponding to 8 tablets/day). Drug-related extrapyramidal symptoms: For the treatment of drug-related extrapyramidal symptoms, ½–1 tablet is administered 2–3 times daily concomitantly with the neuroleptic (corresponding to 2–6 mg Biperiden hydrochloride/day), depending on the severity of the symptoms. Children and adolescents (up to 18 years) SUMMARY OF PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS Pa ge 2 von 8 Akineton 2 mg For the treatment of drug-induced extrapyramidal symptoms, children from 3 to 15 years receive 1– 3 times daily 1/2–1 tablet (equivalent to 1–6 mg biperiden hydrochloride/ day). -

A Brief Overview of Psychotropic Medication Use for Persons with Intellectual Disabilities

A BRIEF OVERVIEW OF PSYCHOTROPIC MEDICATION USE FOR PERSONS WITH INTELLECTUAL DISABILITIES INTRODUCTION Individuals with intellectual disabilities are not uncommonly prescribed psychotropic medications. Too often, historically, such agents have been used to try to improve behavioral control without adequate understanding of the antecedents, purpose, and reinforcement of the problematic behavior. While an individual with an intellectual disability may experience a depressive, anxiety, or psychotic disorder in the more typical sense some individuals experience a pattern of anxiety/alarm/arousal leading to affective dysregulation and impulsive behavior. The anxiety can be stimulated by environmental change, physical discomfort, cues related to past trauma, overstimulation, boredom, confusion, or other unpleasant states. Addressing what is causing the distress or reinforcing the behavioral response is the most important thing (though not always easy). Psychotropic medications may be useful for treating more typically presenting psychiatric illnesses as well as being part of more comprehensive plans to attenuate risk behaviors. An individual with intellectual disabilities who seems sad, is withdrawn, shows low energy and lack of interest, is eating or sleeping more or less, or may be more irritable could be suffering from a depression that needs medication treatment. On the other hand an individual with intellectual disabilities who demonstrates aggression, property destruction, self-injury, or other forms of “dyscontrol” may be helped by medication aimed at blunting the anxiety/alarm and/or blocking its escalation into aggression or other dangerous behaviors. In such instances the medications are just part of an overall strategy or plan to help the individual avoid the “need” to engage in such behavior. -

The Use and Potential Abuse of Anticholinergic

British Journal of Clinical DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2008.03342.x Pharmacology Correspondence Dr Pål Gjerden, Department of Psychiatry, The use and potential abuse Telemark Hospital, N-3710 Skien, Norway. Tel: + 47 3500 3476 Fax: + 47 3500 3187 of anticholinergic E-mail: [email protected] ---------------------------------------------------------------------- antiparkinson drugs in Keywords adverse effects, anticholinergic agents, antiparkinson agents, antipsychotic Norway: a agents, drug abuse ---------------------------------------------------------------------- Received pharmacoepidemiological 9 June 2008 Accepted 18 October 2008 study Published Early View 16 December 2008 Pål Gjerden, Jørgen G. Bramness1 & Lars Slørdal2 Department of Psychiatry,Telemark Hospital, Skien, 1Department of Pharmacoepidemiology, Norwegian Institute of Public Health, Oslo and 2Department of Laboratory Medicine, Children’s and Women’s Health, Norwegian University of Science and Technology,Trondheim, Norway WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ABOUT THIS SUBJECT • Anticholinergic antiparkinson drugs are used to ameliorate extrapyramidal AIMS symptoms caused by either Parkinson’s The use of anticholinergic antiparkinson drugs is assumed to have disease or antipsychotic drugs, but their use shifted from the therapy of Parkinson’s disease to the amelioration in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease is of extrapyramidal adverse effects induced by antipsychotic drugs. There is a considerable body of data suggesting that anticholinergic assumed to be in decline. antiparkinson drugs have a potential for abuse.The aim was to • Patients with psychotic conditions have a investigate the use and potential abuse of this class of drugs in Norway. high prevalence of abuse of drugs, including anticholinergic antiparkinson drugs. METHODS Data were drawn from the Norwegian Prescription Database on sales to a total of 73 964 patients in 2004 of biperiden and orphenadrine, and use in patients with Parkinson’s disease or in patients who were WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS also prescribed antipsychotic agents. -

Oleander and Datura Poisoning: an Update Vijay V Pillay1, Anu Sasidharan2

INVITED ARTICLE Oleander and Datura Poisoning: An Update Vijay V Pillay1, Anu Sasidharan2 ABSTRACT India has a very high incidence of poisoning. While most cases are due to chemicals or drugs or envenomation by venomous creatures, a significant proportion also results from consumption or exposure to toxic plants or plant parts or products. The exact nature of plant poisoning varies from region to region, but certain plants are almost ubiquitous in distribution, and among these, Oleander and Datura are the prime examples. These plants are commonly encountered in almost all parts of India. While one is a wild shrub (Datura) that proliferates in the countryside and by roadsides, and the other (Oleander) is a garden plant that features in many homes. Incidents of poisoning from these plants are therefore not uncommon and may be the result of accidental exposure or deliberate, suicidal ingestion of the toxic parts. An attempt has been made to review the management principles with regard to toxicity of these plants and survey the literature in order to highlight current concepts in the treatment of poisoning resulting from both plants. Keywords: Cerbera, Datura, Nerium, Oleander, Plant poison, Thevetia. Indian Journal of Critical Care Medicine (2019): 10.5005/jp-journals-10071-23302 INTRODUCTION 1Department of Forensic Medicine and Toxicology, Poison Control India being a tropical country is host to a rich and varied Centre, Amrita School of Medicine, Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham, flora encompassing thousands of plants; and while most are Kochi, Kerala, India nonpoisonous, a significant few possess toxic properties of varying 2Department of Forensic Medicine and Toxicology, Forensic Pathology degree.