Dolors Bramon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mocions Aprovades Per La Suficiència Financera Dels Ens Locals

Mocions aprovades per la suficiència financera dels ens locals TIPUS ENS NOM Comarca Ajuntament Alamús Segrià Ajuntament Albagés Garrigues Ajuntament Albatàrrec Segrià Ajuntament Alcanó Segrià Ajuntament Aldea Baix Ebre Ajuntament Alella Maresme Ajuntament Alguaire Segrià Ajuntament Alió Alt Camp Ajuntament Almenar Segrià Ajuntament Alt Àneu Pallars Sobirà Ajuntament Altafulla Tarragonès Ajuntament Amer Selva Ajuntament Ametlla del Vallès Vallès Oriental Ajuntament Ampolla Baix Ebre Ajuntament Anglès Selva Ajuntament Arboç Baix Penedès Ajuntament Argelaguer Garrotxa Ajuntament Arnes Terra Alta Ajuntament Ascó Ribera d'Ebre Ajuntament Avellanes i Santa Linya Noguera Ajuntament Avià Berguedà Ajuntament Avinyonet de Puigventós Alt Empordà Ajuntament Badalona Barcelonès Ajuntament Baix Pallars Pallars Sobirà Ajuntament Banyoles Pla de l'Estany Ajuntament Barbens Pla d'Urgell Ajuntament Barberà del Vallès Vallès Occidental Ajuntament Begues Baix Llobregat Ajuntament Begur Baix Empordà Ajuntament Bellcaire d'Empordà Baix Empordà Ajuntament Benavent de Segrià Segrià Ajuntament Bescanó Gironès Ajuntament Bigues i Riells Vallès Oriental Ajuntament Bisbal del Penedès Baix Penedès Ajuntament Bisbal d'Empordà Baix Empordà Ajuntament Blanes Selva Ajuntament Bòrdes, es Val d´Aran Ajuntament Borges del Camp Baix Camp Ajuntament Borrassà Alt Empordà Ajuntament Borredà Berguedà Ajuntament Bruc Anoia Ajuntament Brunyola Selva Ajuntament Cabó Alt Urgell Ajuntament Calaf Anoia Ajuntament Caldes de Montbui Vallès Oriental Ajuntament Calella Maresme Ajuntament -

A New Decapod Crustacean Assemblage from the Lower Aptian of La Cova Del Vidre (Baix Ebre, Province of Tarragona, Catalonia)

Accepted Manuscript A new decapod crustacean assemblage from the lower Aptian of La Cova del Vidre (Baix Ebre, province of Tarragona, Catalonia) Àlex Ossó, Barry van Bakel, Fernando Ari Ferratges-Kwekel, Josep Anton Moreno- Bedmar PII: S0195-6671(17)30554-2 DOI: 10.1016/j.cretres.2018.07.011 Reference: YCRES 3924 To appear in: Cretaceous Research Received Date: 27 December 2017 Revised Date: 11 June 2018 Accepted Date: 19 July 2018 Please cite this article as: Ossó, À., van Bakel, B., Ferratges-Kwekel, F.A., Moreno-Bedmar, J.A., A new decapod crustacean assemblage from the lower Aptian of La Cova del Vidre (Baix Ebre, province of Tarragona, Catalonia), Cretaceous Research (2018), doi: 10.1016/j.cretres.2018.07.011. This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain. ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT 1 A new decapod crustacean assemblage from the lower Aptian of La Cova del Vidre 2 (Baix Ebre, province of Tarragona, Catalonia) 3 4 Àlex Ossó a, Barry van Bakel b, Fernando Ari Ferratges-Kwekel c, Josep Anton Moreno- 5 Bedmar d,* 6 7 a Llorenç de Vilallonga, 17B, 1er-1ª. 43007 Tarragona, Catalonia 8 b Oertijdmuseum, Bosscheweg 80, 5283 WB Boxtel, the Netherlands 9 c Área de Paleontología, Departamento de Ciencias de la Tierra, Universidad de Zaragoza, Zaragoza, Spain 10 d Instituto de Geología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Ciudad Universitaria, Coyoacán, Ciudad de 11 México, 04510 Mexico 12 13 14 * Corresponding author. -

021505.Pdf (146.5Kb)

ABOUT THE CONCEPT OF ONOMASTIC IDENTITY: THE PRIVILEGES' PARCHMENTS OF THE CITY OF BALAGUER (1211-1352) MOISÉS SELFA UNIVERSITAT DE LLEIDA SpaIN Date of receipt: 10th of March, 2010 Final date of acceptance: 4th of February, 2014 ABSTRACT This paper is an analysis of the name that appears in the Pergamins de Privilegis of the city of Balaguer. The historical period that we take for this study includes the years 1211-1352. The structural study of the systems of designation allows us to say that these spread and claim an identity to a concrete geographical space, the city of Balaguer of the 13th and 14th centuries; that the first name of the inhabitants of Balaguer in the Late Middle Ages are faithful to the trends set by the fashion onomastic predominantly in the Catalonia at that time and that the anthroponomy of Balaguer of the historic time covered offers as majority the surnames that come from place names. All these features allow us to talk of onomastic trends that confer identity to a population in constant geographical movement. KEY WORDS Onomastic, Identity, Privilegis, Anthroponymy, Toponymy. CAPITALIA VERBA Onomastica, Identitas, Privilegia, Anthroponimia, Toponimia. IMAGO TEMPORIS. MEDIUM AEVUM, VIII (2014) 135-149. ISSN 1888-3931 135 136 MOISÉS SELFA 1. The concept of onomastic identity Since ancient times, people have used a name to differentiate themselves from their peers. This name was given to a person in accordance with one of his or her physical or moral characteristics, since they were not given at birth, but as a person matured in life and began to stand out for one of these qualities. -

La Gestió Dels Residus a L'àmbit Municipal

DADES DE RESIDUS MUNICIPALS 2008 Terres de l’Ebre (Baix Ebre, Montsià, Priorat, Ribera d’Ebre i Terra Alta) juliol de 2009 LA GENERACIÓ DE RESIDUS A LES TERRES DE L’EBRE LA GENERACIÓ DE RESIDUS MUNICIPALS Totes les comarques de les Terres de l’Ebre generen menys residus que la mitjana catalana, concretament 1,45 kg/hab/dia. Les comarques que en generen més són Ribera d’Ebre i Priorat, que produeixen 1,54 kg/hab/dia. La comarca que en genera menys és la Terra Alta, amb 1,11 kg/hab/dia. TOTAL GENERACIÓ DE RESIDUS MUNICIPALS (kg/hab/DIA) PER COMARQUES. DADES DE 2008 4,00 3,00 2,00 Kg /hab./dia Kg 1,00 1,44 1,48 1,54 1,54 1,59 1,11 0,00 Baix Ebre Montsià Priorat Ribera d'Ebre Terra Alta Total Catalunya RECOLLIDA SELECTIVA A LES TERRES DE L’EBRE LA RECOLLIDA SELECTIVA Les comarques de les Terres de l’Ebre, en conjunt, són les que més residus recullen selectivament de tot Catalunya, concretament un 38,2% dels residus municipals generats. Ribera d’Ebre, amb el 53,2%, és la comarca que recull selectivament més residus. La segueixen el Montsià (45,6%) i el Priorat (44,2%). RELACIÓ ENTRE RECOLLIDA SELECTIVA I FRACCIÓ RESTA (%) PER COM ARQUES. DADES DE 2008 100,0 90,0 80,0 46,8 54,4 70,0 55,8 63,3 65,6 73,7 60,0 % 50,0 40,0 30,0 53,2 45,6 20,0 44,2 36,7 34,4 26,3 10,0 0,0 Baix Ebre Mont sià Priorat Ribera d'Ebre Terra Alta Total Cat alunya % RS / RM %FR / RM RECOLLIDA SELECTIVA A LES TERRES DE L’EBRE LA MATÈRIA ORGÀNICA El Montsià és la comarca que més matèria orgànica recull selectivament per habitant, molt per sobre de la mitjana catalana. -

Article Journal of Catalan Intellectual History, Volume I, Issue 2, 2011 | Print ISSN 2014-1572 / Online ISSN 2014-1564 DOI 10.2436/20.3001.02.9 | Pp

article Journal of Catalan IntelleCtual HIstory, Volume I, Issue 2, 2011 | Print ISSN 2014-1572 / online ISSN 2014-1564 DoI 10.2436/20.3001.02.9 | Pp. 123-130 http://revistes.iec.cat/index.php/JoCIH On the Philosophers’ Exile and Pere Coromines’ Desterro1 Jordi Sales-Coderch universitat de Barcelona. facultat de filosofia Departament de filosofia teorètica i Pràctica. Barcelona [email protected] abstract This article suggests a reconsideration of the term “exile” as it is referred to the Cata- lan thinkers since the armed conflict of 1936-1939. “Inner exile” is a label whose use frequently obeys to ideological and personal considerations rather than to an objective characterisation. Thus, what serves to discredit some authors is neglected for others who enjoy a positive characterisation . This is also the case of “exile”. Pere Coromines [1870-1939] stands here as an initial example. key words exile, inner exile, Pere Coromines. 1 1. By Way of Introduction: An Uncomfortable Question In order to contextualise what I will say about some key figures in Catalan culture and, above all, to indicate the direction of my current work on essays in Catalan and their possible and difficult standardised acceptance, I will begin with a question expressed by Marta Pessarrodona. In the introduction to França 1939. La cultura catalana exiliada (France 1939. Catalan Culture Exiled), her coherent, useful and ambitious book on a very complicated issue and which has the particular merit of having been produced at all, she writes: “I have also repeatedly asked myself why important figures at a political, intellectual and artistic level, such as Lluís Nicolau d’Olwer or Pere Coromines, are so unfa- 1 Pere Coromines, as the author explains in the text, opts for the use of this word, desterro (ban- ishment), instead of the word exili because of its connotations. -

VINARÒS Comarca: Baix Maestrat Idioma: Valenciano Ayuntamiento

VINARÒS Comarca: Baix Maestrat Idioma: Valenciano Ayuntamiento Dirección: Plaza Parroquial, 12 CP: 12500 Tel: 964 407 700 Fax: 964 407 701 Web: www.vinaros.org E-Mail: [email protected] Corporación Municipal Alcaldía Concejalías Mujeres 10 Hombres 1 10 A) POBLACIÓN: Años 1981 1991 2001 2003 Habitantes 17742 20026 22113 23807 Información actualizada relativa a la población en http://www.ive.es/ive/mun/fichas/cas/Fichas/12138.pdf B) RECURSOS DEL MUNICIPIO B1) Infraestructuras y servicios Infraestructuras deportivas Pabellón Polideportivo.Avda. Tarragona.Tel: 964 455415 Club Náutico. C/ Varadero,s/n. Tel: 964 452907 Club de Tennis, Aptdo. de Correos,272 Patronato de Deportes. C/ Carreró, 51. Tel: 964 454 608 Piscina Municipal Climatizada. Avda. Mª Auxiliardora. Tel: 964 451423 Infraestructuras culturales Auditori Municipal “ Wenceslao Ayguals de Izco”. Pl. San Agustino Biblioteca Pública Municipal. Av. Libertad.Tel: 964 400281 Museo Municipal. C/ Santa Ruta Plaza de Toros. C/ Varadero. Tel: 964 45148 Servicios públicos Administración de Hacienda. San Francisco, 100.Tel: 964 454111 Bomberos. 964 474006 Correos. Pl. Jovellar. 964 451269 Cruz Roja. Pilar, 73. 964 450856 Gas. San Juan, 18. 964 451124 Guardia Civil. Av. Castellón, 15. 964 400384 Información Turística. Pl. Jovellar, s/n. 964 649116 [email protected] Oficina de turismo. Paseo Colón s/n 964 453334 [email protected] www.comunidad- valenciana.es INEM. Santa Marta, 9. Tel: 964 450516 Juzgados. Pl. San Antonio, 1-2-3. 964 450091 964 450082 964 454600 OMIC. Pl. Jovellar, s/n. 964 649116 Policía Local. Pl. Parroquial, 12. 964 450200 Recaudación de Tributos. Juan de Giner Ruiz, 5. -

Guia Comunicació 2014 Alt Camp Baix Camp Baix Ebre Baix Penedès Conca De Barberà Montsià Priorat Ribera D’Ebre Tarragonès Terra Alta

guia comunicació 2014 Alt Camp Baix Camp Baix Ebre Baix Penedès Conca de Barberà Montsià Priorat Ribera d’Ebre Tarragonès Terra Alta Col·legi de Periodistes de Catalunya Demarcació de Tarragona Demarcació Terres de l’Ebre Col·legi de Periodistes de Catalunya Demarcació de Tarragona Demarcació Terres de l’Ebre Carrer d’August, 5, 1r 1a 43003 TARRAGONA Tel. 977 245 454 Fax 977 250 519 [email protected] Plaça Ramon Cabrera, 7, 1r 43500 TORTOSA Tel. 977 442 490 [email protected] Edita: Col·legi de Periodistes de Catalunya Demarcació de Tarragona i Demarcació Terres de l’Ebre http://www.periodistes.org Tancament de l’edició: Juny de 2014 Coordinació i redacció: Laura Casadevall Disseny i Impressió: Impremta Virgili · Tarragona Dipòsit Legal: T-1.025-14 PRESENTACIÓ es demarcacions de Tarragona i de les Terres de l’Ebre del Col·legi de Periodistes de Catalunya Lus presenten aquesta guia que, sobretot, vol ser una eina de treball tant per als professionals de la comunicació com per aquelles entitats, institucions o persones que han de contactar amb els mitjans de comunicació. Pel que fa a la seva estructura, pensada sobretot per facilitar la localització de la dada que es busca el més ràpidament possible, es divideix en diversos apartats. Un primer bloc es refereix als mitjans de comunicació, agrupats segons el seu suport (premsa escrita, diaris digitals, publicacions comarcals i mitjans audiovisuals). Un segon bloc es refereix a entitats i empreses, des dels partits po- lítics als centres universitaris, passant per alguns dels principals agents econòmics de la demarcació. -

Terra Alta Greenway (Tarragona)

Terra Alta Greenway Terra Alta is a rural area of Cataluña dotted with almond and pine groves through which a few trains used to run up until 1973. Now we can make use of the disused rail bed of this forgotten railway to travel through the spectacular countryside around the Sierra de Pandols ridge and the Beceite heights. A journey through tunnels and over viaducts takes us from Aragon to the Ebro. TECHNICAL DATA CONDITIONED GREENWAY Spectacular viaducts and tunnels between the ravines of the Canaletas river. LOCATION Between the stations of Arnes-Lledó and El Pinell de Brai TARRAGONA Length: 23 km Users: * * Punctual limitations due to steep slopes in la Fontcalda Type of surface: Asphalt Natural landscape: Forests of pine trees. Karst landscape of great beauty: cannons, cavities Cultural Heritage: Sanctuary of Fontcalda (S. XVI). Convent of Sant Salvador d'Horta in Horta. Church of Sant Josep en Bot Infrastructure: Condidtioned Greenway. 20 tunnels. 5 viaducts How to get there: To all the towns: HIFE Bus Company Connections: Tarragona: 118 Km. to Arnés-Lledó Barcelona: 208 Km. to Arnés-Lledó Castellón de la Plana: 169 Km. to Arnés-Lledó Maps: Military map of spain. 1:50.000 scale 470, 495, 496 and 497 sheets Official road map of the Ministry of Public Works Ministerio de Fomento More information on the Greenways guide Volume 1 Attention: Lack of lighting in some tunnels by vandalism. It is recommended to use a torch DESCRIPTION Km. 0 / Km. 13 / Km. 17,5 / Km. 23,7 Km 0 The Greenway begins at the Arnes-Lledó station alongside the river Algars which at this point forms the border between the autonomous communities of Aragon and Cataluña. -

Paral·Lelismes Lèxics Entre Els Parlars Del Priorat I El Subdialecte Tortosí1

Paral·lelismes lèxics entre els parlars del Priorat i el subdialecte tortosí1 Emili Llamas Puig Universitat Rovira i Virgili Justificació L’estudi lingüístic dels diferents parlars que conformen la llengua catalana ens ajuda a fer-nos un dibuix més precís de la riquesa dialectal que dona color a la nostra llengua. Estudiar amb profunditat els nostres parlars és alhora conèixer els nostres pobles, els nostres costums i, en definitiva, conèixer diferents maneres de veure i entendre el món que ens envolta. Cal doncs, reivindicar un dels patrimonis immaterials més valuosos que tenim, els nostres parlars. El fet que l’objecte d’estudi de la meva tesi doctoral sigui la comarca del Priorat respon a motius personals (vincles familiars i sentimentals) i científics (aquest territori no disposava d’un estudi geolingüístic exhaustiu). Però pel que aquí ens interessa hi ha encara un altre motiu per estudiar els parlars del Priorat i és el fet que la comarca estigui situada en una cruïlla de trets lingüístics que dona a aquests parlars una fesomia heterogènia i amb personalitat pròpia i diferenciada dels de les comarques veïnes (Ribera d’Ebre, Baix Camp i Garrigues). Aquesta particularitat fa que l’estudi d’aquests parlars sigui encara més atractiu. Breu descripció històrica i geogràfica2 La comarca del Priorat té 496,20 km2 i és vertebrada pel massís de Montsant, de la Serralada Prelitoral, a cavall entre el Camp de Tarragona i les Terres de l’Ebre.3 La 1 Aquest article és un dels resultats de la tesi doctoral “Els parlars del Priorat. Estudi geolingüístic” (inèdita), investigació que s’ha pogut dur a terme gràcies a l’obtenció d’una Beca de Recerca Predoctoral del Programa de Personal Investigador en Formació, concedida pel Departament de Filologia Catalana de la Universitat Rovira i Virgili. -

Fitxa Comarcal Del Baix Ebre

Fitxa comarcal Fitxa comarcal del Baix Ebre I Dades bàsiques, any 2007 I Densitat de Població Superfície Municipi població (2006) (km2) (hab/km2) Aldea, l' 3.795 35,21 107,78 Aldover 893 20,2 44,21 Alfara de Carles 341 63,87 5,34 Ametlla de Mar, l' 6.744 66,86 100,87 Ampolla, l' 2.613 35,65 73,29 Benifallet 790 62,42 12,66 Camarles 3.371 25,16 133,98 Deltebre 10.811 107,44 100,62 Paüls 602 43,83 13,73 Perelló, el 2.504 100,67 24,87 Roquetes 7.444 136,92 54,37 Tivenys 916 53,54 17,11 Tortosa 34.266 218,51 156,82 Xerta 1.278 32,39 39,46 Baix Ebre 76.368 1002,72 76,16 Font: Idescat Fitxa comarcal Fitxa comarcal del Baix Ebre I Dades agrícoles i ramaderes del Baix Ebre I Explotacions i places ramaderes Baix Ebre CATALUNYA Superfície de secà Superfície de reg Superfície Conreu Explotacions Places de bestiar Explotacions Places de bestiar (ha) (ha) total (ha) HORTALISSES 2 1.391 1.393 PORCÍ 62 79.261 7.305 6.066.901 CEREALS 84 9.213 9.297 ENGREIX 38 68.436 4.467 5.474.707 ARRÒS - 9.085 9.085 REPRODUCCIÓ 24 10.825 2.838 592.194 FARRATGES 33 71 104 BOVÍ 42 9.298 7.001 801.221 FRUITA FRESCA 146 296 442 VAQUES DE LLET - - 1.765 103.244 CÍTRICS - 5.025 5.025 VAQUES DE CARN 22 2.589 1.806 99.471 FRUITA SECA 1.064 229 1.293 VEDELLS 20 6.709 3.430 598.506 OLIVERA 26.355 1.014 27.369 OVÍ I CABRUM 183 49.476 3.935 1.286.831 VINYA 54 - 54 OVELLES 128 26.945 2.744 838.656 ALTRES CONREUS 4.847 192 5.039 CABRES 51 9.749 933 122.387 XAIS 4 12.782 258 325.788 TOTAL 32.585 17.431 50.016 Font: Gabinet tècnic del DAR. -

Lencianas Del Baix Maestrat Y Els Ports, Ii

Flora Montiberica 55: 29-37 (3-X-2013). ISSN: 1138-5952, edic. digital: 1998-799X APORTACIONES BOTÁNICAS PARA LAS COMARCAS VA- LENCIANAS DEL BAIX MAESTRAT Y ELS PORTS, II Romà SENAR LLUCH C/César Cataldo, 13. 12580-Benicarló (Castellón) [email protected] RESUMEN: se presentan las citas de 40 plantas vasculares observadas en las co- marcas del Baix Maestrat y Els Ports (Castellón), mejorando con esta información el conocimiento de su distribución. Palabras clave: Plantas vasculares, distribución, Baix Maestrat, Els Ports, Castellón, Comunidad Valenciana, España. ABSTRACT: Botanical contributions for the valentians counties Baix Maestrat and Els Ports, II. Records about 40 vascular plants observed in Baix Maestrat and Els Ports regions (Castelló, Valencian Community), improving the knowledge of their distribution area. Key words: Vascular plants, distribution, Baix Maestrat, Els Ports, Castellón, Valencian Community, Spain. INTRODUCCIÓN obra se ha seguido la nomenclatura propues- ta por MATEO & CRESPO (2009). Abrevia- Continuando en la línea de anteriores mos Banco de Datos de Biodiversidad de trabajos, se pretende seguir contribuyendo la Comunidad Valenciana como BDBCV. con los estudios corológicos de algunas zonas del norte del País Valenciano. Con este trabajo se aportan las citas de algunas LISTADO DE PLANTAS plantas de interés florístico para las res- pectivas comarcas, con la finalidad de Arum italicum Mill. aumentar los conocimientos de su área de CASTELLÓN: 30TYK4399, Morella, río distribución. Bergantes, 740 m, 29-VI-2010, R. Senar. En el presente trabajo se detallan las Se aporta una nueva cita para esta es- citas de las plantas con cierto interés co- pecie que habita las zonas umbrías y rológico encontradas durante los años húmedas de las riberas. -

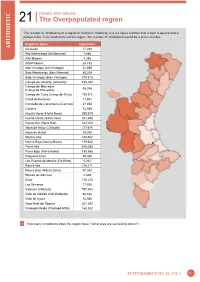

The Overpopulated Region

Powers and radicals 21 The Overpopulated region The number of inhabitants of a region of Valencia (Valencia) is a six-figure number that is both a square and a HMETIC T perfect cube. If six inhabitants left the region, the number of inhabitants would be a prime number. Region in Spain Population ARI Alcalatén 17,226 Alto Maestrazgo (Alt Maestrat) 7,846 Alto Mijares 4,386 Alto Palancia 24,732 Alto Vinalopó (Alt Vinalopó) 52,899 Bajo Maestrazgo (Baix Maestrat) 80,334 Bajo Vinalopó (Baix Vinalopó) 279,815 Campo de Alicante (Alacantí) 455,292 Campo de Morvedre 85,355 (Camp de Morvedre) Campo de Turia (Camp de Túria) 135,373 Canal de Navarrés 17,691 Condado de Cocentaina (Comtat) 27,854 Costera 72,089 Huerta Norte (Horta Nord) 209,519 Huerta Oeste (Horta Oest) 331,698 Huerta Sur (Horta Sud) 163,253 Hoya de Alcoy (L'Alcoià) 117,649 Hoya de Buñol 39,768 Marina Alta 188,567 Marina Baja (Marina Baixa) 179,546 Plana Alta 248,098 Plana Baja (Plana Baixa) 185,986 Requena-Utiel 39,386 Los Puertos de Morella (Els Ports) 5,262 Ribera Alta 216,211 Ribera Baja (Ribera Baixa) 80,360 Rincón de Ademuz 2,605 Safor 176,238 Los Serranos 17,936 Valencia (València) 797,654 Valle de Albaida (Vall d'Albaida) 90,783 Valle de Ayora 10,566 Vega Baja del Segura 361,292 Vinalopó Medio (Vinalopó Mitjà) 168,532 How many inhabitants does the region have? What area are we talking about?? ACTIVIDADES PARA EL AULA 1 Powers and radicals 21 The Overpopulated region MATERIAL A CASIO fx-991EX/CLASSWIZ or similar HMETIC Educational Level T High School PEDAGOGICAL AND TECHNICAL GUIDELINES ARI • Many problems can be solved in different ways.