Richard Ennis, Alia Long Mick

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

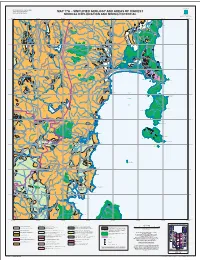

Map 17A − Simplified Geology

MINERAL RESOURCES TASMANIA MUNICIPAL PLANNING INFORMATION SERIES TASMANIAN GEOLOGICAL SURVEY MAP 17A − SIMPLIFIED GEOLOGY AND AREAS OF HIGHEST MINERAL RESOURCES TASMANIA Tasmania MINERAL EXPLORATION AND MINING POTENTIAL ENERGY and RESOURCES DEPARTMENT of INFRASTRUCTURE SNOW River HILL Cape Lodi BADA JOS psley A MEETUS FALLS Swan Llandaff FOREST RESERVE FREYCINET Courland NATIONAL PARK Bay MOULTING LAGOON LAKE GAME RESERVE TIER Butlers Pt APSLEY LEA MARSHES KE RAMSAR SITE ROAD HWAY HIG LAKE LEAKE Cranbrook WYE LEA KE RIVER LAKE STATE RESERVE TASMAN MOULTING LAGOON MOULTING LAGOON FRIENDLY RAMSAR SITE BEACHES PRIVATE BI SANCTUARY G ROAD LOST FALLS WILDBIRD FOREST RESERVE PRIVATE SANCTUARY BLUE Friendly Pt WINGYS PARRAMORES Macquarie T IER FREYCINET NATIONAL PARK TIER DEAD DOG HILL NATURE RESERVE TIER DRY CREEK EAST R iver NATURE RESERVE Swansea Hepburn Pt Coles Bay CAPE TOURVILLE DRY CREEK WEST NATURE RESERVE Coles Bay THE QUOIN S S RD HAZA THE PRINGBAY THOUIN S Webber Pt RNMIDLAND GREAT Wineglass BAY Macq Bay u arie NORTHE Refuge Is. GLAMORGAN/ CAPE FORESTIER River To o m OYSTER PROMISE s BAY FREYCINET River PENINSULA Shelly Pt MT TOOMS BAY MT GRAHAM DI MT FREYCINET AMOND Gates Bluff S Y NORTH TOOM ERN MIDLA NDS LAKE Weatherhead Pt SOUTHERN MIDLANDS HIGHWA TI ER Mayfield TIER Bay Buxton Pt BROOKERANA FOREST RESERVE Slaughterhouse Bay CAPE DEGERANDO ROCKA RIVULET Boags Pt NATURE RESERVE SCHOUTEN PASSAGE MAN TAS BUTLERS RIDGE NATURE RESERVE Little Seaford Pt SCHOUTEN R ISLAND Swanp TIE FREYCINET ort Little Swanport NATIONAL PARK CAPE BAUDIN -

250 State Secretary: [email protected] Journal Editors: [email protected] Home Page

Tasmanian Family History Society Inc. PO Box 191 Launceston Tasmania 7250 State Secretary: [email protected] Journal Editors: [email protected] Home Page: http://www.tasfhs.org Patron: Dr Alison Alexander Fellows: Dr Neil Chick, David Harris and Denise McNeice Executive: President Anita Swan (03) 6326 5778 Vice President Maurice Appleyard (03) 6248 4229 Vice President Peter Cocker (03) 6435 4103 State Secretary Muriel Bissett (03) 6344 4034 State Treasurer Betty Bissett (03) 6344 4034 Committee: Judy Cocker Margaret Strempel Jim Rouse Kerrie Blyth Robert Tanner Leo Prior John Gillham Libby Gillham Sandra Duck By-laws Officer Denise McNeice (03) 6228 3564 Assistant By-laws Officer Maurice Appleyard (03) 6248 4229 Webmaster Robert Tanner (03) 6231 0794 Journal Editors Anita Swan (03) 6326 5778 Betty Bissett (03) 6344 4034 LWFHA Coordinator Anita Swan (03) 6394 8456 Members’ Interests Compiler Jim Rouse (03) 6239 6529 Membership Registrar Muriel Bissett (03) 6344 4034 Publications Coordinator Denise McNeice (03) 6228 3564 Public Officer Denise McNeice (03) 6228 3564 State Sales Officer Betty Bissett (03) 6344 4034 Branches of the Society Burnie: PO Box 748 Burnie Tasmania 7320 [email protected] Devonport: PO Box 587 Devonport Tasmania 7310 [email protected] Hobart: PO Box 326 Rosny Park Tasmania 7018 [email protected] Huon: PO Box 117 Huonville Tasmania 7109 [email protected] Launceston: PO Box 1290 Launceston Tasmania 7250 [email protected] Volume 29 Number 2 September 2008 ISSN 0159 0677 Contents Editorial ................................................................................................................ -

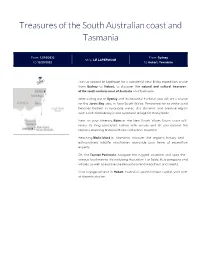

Print Cruise Information

Treasures of the South Australian coast and Tasmania From 12/16/2022 From Sydney Ship: LE LAPEROUSE to 12/23/2022 to Hobart, Tasmania Join us aboard Le Lapérouse for a wonderful new 8-day expedition cruise from Sydney to Hobart, to discover thenatural and cultural treasures of the south-eastern coast of Australia and Tasmania. After sailing out of Sydney and its beautiful harbour, you will set a course for the Jervis Bay area, in New South Wales. Renowned for its white-sand beaches bathed in turquoise water, this dynamic and creative region with a rich biodiversity is also a popular refuge for many birds. Next on your itinerary, Eden on the New South Wales South coast will reveal its long-associated history with whales and let you explore the region's stunning National Parks and scenic coastline. Reaching Maria Island in Tasmania, discover the region's history and extraordinary wildlife sanctuaries alongside your team of expedition experts. On the Tasman Peninsula, navigate the rugged coastline and spot the various local marine life including Australian Fur Seals, little penguins and whales, as well as explore the beautiful inland woodland and forests. Your voyage will end in Hobart, Australia's second oldest capital, your port of disembarkation. The information in this document is valid as of 9/25/2021 Treasures of the South Australian coast and Tasmania YOUR STOPOVERS : SYDNEY Embarkation 12/16/2022 from 4:00 PM to 5:00 PM Departure 12/16/2022 at 6:00 PM Nestled around one of the world’s most beautiful harbours,Sydney is both trendy and classic, urbane yet laid-back. -

Overview of Tasmania's Offshore Islands and Their Role in Nature

Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania, Volume 154, 2020 83 OVERVIEW OF TASMANIA’S OFFSHORE ISLANDS AND THEIR ROLE IN NATURE CONSERVATION by Sally L. Bryant and Stephen Harris (with one text-figure, two tables, eight plates and two appendices) Bryant, S.L. & Harris, S. 2020 (9:xii): Overview of Tasmania’s offshore islands and their role in nature conservation.Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania 154: 83–106. https://doi.org/10.26749/rstpp.154.83 ISSN: 0080–4703. Tasmanian Land Conservancy, PO Box 2112, Lower Sandy Bay, Tasmania 7005, Australia (SLB*); Department of Archaeology and Natural History, College of Asia and the Pacific, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 2601 (SH). *Author for correspondence: Email: [email protected] Since the 1970s, knowledge of Tasmania’s offshore islands has expanded greatly due to an increase in systematic and regional surveys, the continuation of several long-term monitoring programs and the improved delivery of pest management and translocation programs. However, many islands remain data-poor especially for invertebrate fauna, and non-vascular flora, and information sources are dispersed across numerous platforms. While more than 90% of Tasmania’s offshore islands are statutory reserves, many are impacted by a range of disturbances, particularly invasive species with no decision-making framework in place to prioritise their management. This paper synthesises the significant contribution offshore islands make to Tasmania’s land-based natural assets and identifies gaps and deficiencies hampering their protection. A continuing focus on detailed gap-filling surveys aided by partnership restoration programs and collaborative national forums must be strengthened if we are to capitalise on the conservation benefits islands provide in the face of rapidly changing environmental conditions and pressure for future use. -

Nowhere Else on Earth

Nowhere Else on Earth: Tasmania’s Marine Natural Values Environment Tasmania is a not-for-profit conservation council dedicated to the protection, conservation and rehabilitation of Tasmania’s natural environment. Australia’s youngest conservation council, Environment Tasmania was established in 2006 and is a peak body representing over 20 Tasmanian environment groups. Prepared for Environment Tasmania by Dr Karen Parsons of Aquenal Pty Ltd. Report citation: Parsons, K. E. (2011) Nowhere Else on Earth: Tasmania’s Marine Natural Values. Report for Environment Tasmania. Aquenal, Tasmania. ISBN: 978-0-646-56647-4 Graphic Design: onetonnegraphic www.onetonnegraphic.com.au Online: Visit the Environment Tasmania website at: www.et.org.au or Ocean Planet online at www.oceanplanet.org.au Partners: With thanks to the The Wilderness Society Inc for their financial support through the WildCountry Small Grants Program, and to NRM North and NRM South. Front Cover: Gorgonian fan with diver (Photograph: © Geoff Rollins). 2 Waterfall Bay cave (Photograph: © Jon Bryan). Acknowledgements The following people are thanked for their assistance The majority of the photographs in the report were with the compilation of this report: Neville Barrett of the generously provided by Graham Edgar, while the following Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies (IMAS) at the additional contributors are also acknowledged: Neville University of Tasmania for providing information on key Barrett, Jane Elek, Sue Wragge, Chris Black, Jon Bryan, features of Tasmania’s marine -

A Colony of Convicts

A Colony of Convicts The following information has been taken from https://www.foundingdocs.gov.au/ Documenting a Democracy ‘Governor Phillip’s Instructions 25 April 1787’ The British explorer Captain James Cook landed in Australia in 1770 and claimed it as a British territory. Six years after James Cook landed at Botany Bay and gave the territory its English name of 'New South Wales', the American colonies declared their independence and war with Britain began. Access to America for the transportation of convicts ceased and overcrowding in British gaols soon raised official concerns. In 1779, Joseph Banks, the botanist who had travelled with Cook to New South Wales, suggested Australia as an alternative place for transportation. The advantages of trade with Asia and the Pacific were also raised, alongside the opportunity New South Wales offered as a new home for the American Loyalists who had supported Britain in the War of Independence. Eventually the Government settled on Botany Bay as the site for a colony. Secretary of State, Lord Sydney, chose Captain Arthur Phillip of the Royal Navy to lead the fleet and be the first governor. The process of colonisation began in 1788. A fleet of 11 ships, containing 736 convicts, some British troops and a governor set up the first colony of New South Wales in Sydney Cove. Prior to his departure for New South Wales, Phillip received his Instructions from King George III, with the advice of his ‘Privy Council'. The first Instructions included Phillip's Commission as Captain-General and Governor-in-Chief of New South Wales. -

TRAVEL Maria Island, Tasmania

TRAVEL Maria Island, Tasmania Maria Island Walk, Tasmania. maria island walk ECOGNISED AS ONE OF Australia’s truly Routstanding experiences, the four-day Maria Island Walk is a delightful blend of rare wildlife, fascinating history, island tranquillity and gourmet delights. hbA Set on a beautiful island national park off Tasmania’s tas east coast, small groups of just 10 guests and two AG TRAVEL friendly guides explore the pristine beaches, tall ancient forests and world heritage sites by day before, each Dates: night, relaxing at a mouthwatering candlelit dinner. 19–23 february 2021 Maria Island is a Noah’s Ark for rare animals and 24–28 November 2021 birds, some of which are found nowhere else. It is email: known as one of, if not the best, places in Australia [email protected] to see wombats in the wild. phone: 0413 560 210 Itinerary 1 TRAVEL Maria Island, Tasmania The Painted Cliffs are one of Maria Island’s more memorable spectacles. Itinerary taking 360 degree views. Or save the climb Day 1 Arrival in Hobart Day 3 Maria Island Walk (domestic airfare not included) for Bishop and Clerk, with its fantastic sea and coastline vistas (these are optional). Make your own way to your hotel Walk from Riedle Bay across the rare land Finish the day with a sumptuous banquet in (Ibis Styles Hobart) formation of the isthmus to Shoal Bay for a the historic colonial home once occupied by stroll across five fabulous beaches. As you Italian entrepreneur Diego Bernacchi. This is walk, your knowledgeable guides will share also your accommodation for the night. -

1984/37. the Schouten Island Coalfield

U~/984_.J7 ij0 1984/37. The Schouten Island coalfield CoA. Dacon K.D. Corbett Abstract Schouten Island is located 1.6 km south of the Freycinet Peninsula. A large north-south trending fault divides the island into two geologically distinct parts. The higher relief of the eastern part, which is underlain by Devonian granite, contrasts sharply with the more gentle topography of the western part, which is underlain by Jurassic dolerite and Parmeener Super-Group rocks. During small-scale mining activity in the 1840's coal was won from two adits and two shafts in the northern part of the island. The island was declared a National Park in 1967 and is therefore now exempt from provisions of the Mining Act, 1929. LOCATION AND ACCESS Schouten Island lies 1.6 km south of the southern tip of Freycinet Peninsula on the east coast of Tasmania. Access by boat is 19 km from Coles Bay or 24 km from Swansea. The principal anchorages for small boats are at Crocketts Bay or Moreys Bay on the northern coast of the island. GEOLOGY The island, which has an area of 28 km', has been mapped by Keid (in Hills et al., 1922), Reid (1924), Hughes (1959) and Corbett (in prep.). A major N-S trending fault divides the island into a rugged eastern part underlain by Devonian granitic rocks (mainly pink medium to coarse grained adamellite), and a western part with subdued topography underlain by Jurassic dolerite and Parmeener Super-Group rocks. QUaternary deposits include recent coastal sand dunes, patches of windblown sand on coastal hills, and talus deposits fringing the extensive cap of dolerite west of the fault. -

Great Southern Land: the Maritime Exploration of Terra Australis

GREAT SOUTHERN The Maritime Exploration of Terra Australis LAND Michael Pearson the australian government department of the environment and heritage, 2005 On the cover photo: Port Campbell, Vic. map: detail, Chart of Tasman’s photograph by John Baker discoveries in Tasmania. Department of the Environment From ‘Original Chart of the and Heritage Discovery of Tasmania’ by Isaac Gilsemans, Plate 97, volume 4, The anchors are from the from ‘Monumenta cartographica: Reproductions of unique and wreck of the ‘Marie Gabrielle’, rare maps, plans and views in a French built three-masted the actual size of the originals: barque of 250 tons built in accompanied by cartographical Nantes in 1864. She was monographs edited by Frederick driven ashore during a Casper Wieder, published y gale, on Wreck Beach near Martinus Nijhoff, the Hague, Moonlight Head on the 1925-1933. Victorian Coast at 1.00 am on National Library of Australia the morning of 25 November 1869, while carrying a cargo of tea from Foochow in China to Melbourne. © Commonwealth of Australia 2005 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Commonwealth, available from the Department of the Environment and Heritage. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to: Assistant Secretary Heritage Assessment Branch Department of the Environment and Heritage GPO Box 787 Canberra ACT 2601 The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Australian Government or the Minister for the Environment and Heritage. -

Candidate Information Pack

CANDIDATE INFORMATION PACK Considering Employment in Glamorgan Spring Bay Municipality Updated: August 2020 West Shelley Beach by H Chapman CONTENTS Our Region ............................................................................ 4 Our Municipality ............................................................... 6 Our ultimate vision of long-term success ........................ 7 Our guiding principles ....................................................... 7 Sunset in Swanwick by V Kay Triabunna Marina by J Goodrick Whales in the Bay by S Masterman Sheep auction by S Dunbabin Bluethroat Wrasse by J Smith Cambria Windmill by K Gregson PAGE 3 GSBC CANDIDATE INFORMATION PACK Our Region… The Municipal Environment build upon. Of the total number of interstate and The municipality of Glamorgan Spring Bay is international visitors coming to Tasmania, 30% situated amongst some of the most beautiful come to Glamorgan Spring Bay. Intrastate visitation coastal scenery in Tasmania. It has an area of is also strong, with 53% of dwellings across the 2,522 square kilometres and is bounded by municipality being holiday homes. During holiday the Denison River in the North and the base periods the overall population more than doubles and this has implications for infrastructure and of Bust Me Gall Hill in the South. The western boundary essentially follows the ridgeline of the service provision. The highest numbers of holiday Eastern Tiers. It is 160 kilometres from end to homes are in Coles Bay and Orford. end and contains two significant National Parks, Schools and Childcare Freycinet and Maria Island. Each of the main townships is serviced by a state Glamorgan Spring Bay Council provides a owned primary school (Kindergarten to Grade 6). wide range of services including roads and Triabunna has a district school years 7-10. -

GSBC Harbour Expansion and Maria Island Ferry Terminal Economic

Contents 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Background 1 1.2 Economist & Financial Analysis Advisor 1 1.3 Submission Objectives 1 2. Economic Analysis 3 2.1 Economic Justification 3 2.2 Economic Costs 3 2.3 Economic Benefits (Merit Criterion 1) 3 2.4 Social Benefits (Merit Criterion 2) 4 2.5 Project Delivery (Merit Criterion 3) 4 2.6 Impact of Grant Funding (Merit Criterion 4) 5 3. Economic Results 7 3.1 Sensitivity Testing 7 Appendix A - Dr R.R. Noakes CV 15 Burbury Consulting Pty Ltd ACN 146 719 959 2/2 Gore Street, South Hobart, TAS 7004 P. 03 6223 8007 F. 03 6212 0642 [email protected] www.burburyconsulting.com.au Document Status Rev Approved for Issue Author Status No. Name Date 0 Dr. R. (Bob) Noakes For Approval J. Burbury 14/11/18 ii 1. Introduction 1.1 Background This Report has been prepared to present the findings of a range of economic and financial analyses, which have been completed for Spring Bay Harbour Expansion and Maria Island Ferry Terminal, Triabunna, Tasmania. The findings specifically relate to the preparation of an overall Business Case with two key investment components. These are to support and justify public sector investment in (i) a new public pier on the southern side of the existing pier relics and (ii) in the preservation of the existing historic pier remnants, for future heritage tourism and for Bridport’s historic legacy. Burbury Consulting has prepared the infrastructure drawings, project management plan and infrastructure costings. 1.2 Economist & Financial Analysis Project Advisor Dr Robert (Bob) Noakes is an experienced project/infrastructure economist and financial analyst with more than 40 years experience in Australia and in more than 30 countries in project planning and development studies, with major emphasis on ports, ferry terminals, roads and highways/bridge infrastructure. -

Maria Island

DISCOVER MARIA ISLAND You can bring your bike (or hire one) to tour the island on two wheels, or choose from a range of walks to see the convict reservoir, hop kilns, French’s Farm, the Fossil Cliffs and the stunning Painted Cliffs. If you have time and feel like more of a challenge, take the walk to the summit of Bishop and Clerk or Mt Maria. For the aquatically-inclined, take a swim at one of Maria’s beautiful beaches, or try snorkelling or scuba diving in the marine reserve. You’ll also encounter diverse wildlife here, including Cape Barren Geese, Forester kangaroos and possibly even a member of the resident insurance population of Tasmanian devils. Camping is available on the island and basic accommodation is also available in the Penitentiary. Find out more on eastcoasttasmania.com.au TOWN MAP MARIA ISLAND There are few places as special as Maria Island. This extraordinary national park, located a short distance off the coast from Triabunna, is a blend of World Heritage listed, convict-era architecture, early 20th century industrial heritage, diverse and beautiful natural landscapes and abundant, protected wildlife. MARIA ISLAND TOWN MAP east coast tasmania .com.au Accommodation 6 Maria Island Ferry and Eco Cruises 0419 746 668 Ile du Nord 7 Mount Maria - 2 Maria Island Penitentiary 6256 4772 Cape Boullanger 8 Painted Cliffs - ferry 46 1 Maria Island Camping Ground 6256 4772 9 The Maria Island Guided Walk 0400 882 742 910 5 10 The Maria Island Walk 6234 2999 11 Fossil Attractions, Activities & Adventures 1 2 Bay 3 Bishop and Clerk - Amenities & Services 2 Darlington Probation Station World Heritage Site - 8 11 Parks & Wildlife Service 6257 1420 3 4 East Coast Cruises 6257 1300 5 Fossil Cliffs - 7 DISCOVER MARIA ISLAND Take the short boat journey from Triabunna and spend a day or longer exploring Maria Island.