Coral Amendment 9 Final Environmental Impact Statement (Feis)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Okeanos Explorer ROV Dive Summary

Okeanos Explorer ROV Dive Summary Dive Information General Location General Area Blake Escarpment, US Continental Margin Descriptor Site Name Blake Escarpment South Science Team Leslie Sautter / Cheryl Morrison Leads Expedition Kasey Cantwell Coordinator ROV Dive Bobby Mohr Supervisor Mapping Lead Derek Sowers ROV Dive Name Cruise EX1806 1 Leg - Dive Number DIVE04 Equipment Deployed ROV Deep Discoverer Camera Platform Seirios ☒ CTD ☒ Depth ☒ Altitude ☒ Scanning Sonar ☒ USBL Position ☒ Heading ROV ☒ Pitch ☒ Roll ☒ HD Camera 1 Measurements ☒ HD Camera 2 ☒ Low Res Cam 1 ☒ Low Res Cam 2 ☒ Low Res Cam 3 ☒ Low Res Cam 4 ☒ Low Res Cam 5 Equipment D2 USBL tracking was very poor at 50m. However, after deciding to proceed with the Malfunctions dive, tracking locked in starting 10m later. Likely weird conditions at 50m. Dive Summary: EX1806_DIVE04 ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^ In Water: 2018-06-17T12:24:26.436709 30°, 56.422' N ; 77°, 19.825' W On Bottom: 2018-06-17T13:28:25.988569 30°, 56.408' N ; 77°, 19.711' W ROV Dive Off Bottom: 2018-06-17T19:21:23.549677 Summary 30°, 56.494' N ; 77°, 19.827' W (from processed ROV data) Out Water: 2018-06-17T22:33:19.461489 30°, 56.462' N ; 77°, 19.472' W Dive duration: 10:8:53 Bottom Time: 5:52:57 Max. depth: 1321.0 m Though water samples were collected on this dive, there were issues with sample storage Special Notes and preservation, therefore no water samples were retained nor archived. Sample numbering and data remains the same, as if water sampling did occur. Name Institution email Scientists Involved Adrienne Copeland NOAA OAR OER [email protected] (please provide Amanda Netburn NOAA/OER [email protected] name, location, affiliation, email) Andrea Quattrini Harvey Mudd College [email protected] Andrew Shuler NOAA/JHT, inc. -

Lake Mattamuskeet Frequently Asked Questions

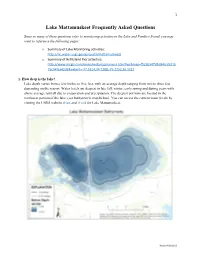

1 Lake Mattamuskeet Frequently Asked Questions Since so many of these questions refer to monitoring activities in the Lake and Pamlico Sound, you may want to reference the following pages: o Summary of Lake Monitoring activities: http://nc.water.usgs.gov/projects/mattamuskeet/ o Summary of Bell Island Pier activities: http://www.arcgis.com/home/webmap/viewer.html?webmap=f52ab347d5e84ccc921b 75c34fea42d5&extent=-77.5214,34.7208,-75.2252,36.3212 1. How deep is the lake? Lake depth varies from a few inches to five feet, with an average depth ranging from two to three feet depending on the season. Water levels are deepest in late fall, winter, early spring and during years with above average rainfall due to evaporation and precipitation. The deepest portions are located in the northwest portion of the lake. (see bathymetric map below). You can access the current water levels by visiting the USGS website (East and West) for Lake Mattamuskeet. Updated 10/12/16 2 2. Why is the lake so high/low? Lake levels fluctuate on a daily, seasonal and yearly basis. Water levels are primarily determined by climatic conditions. Generally, seasonal lake levels follow a pattern of being lower in the summer due to high evaporation rates and higher in fall, winter and spring due to lower evaporation rates and greater precipitation. Lake levels will increase by a few inches after a heavy rain. During wet years with lots of precipitation, water levels will rise; during drought years, water levels will fall. You can access current water levels by visiting the USGS website for Lake Mattamuskeet (East and West). -

Coelenterata: Anthozoa), with Diagnoses of New Taxa

PROC. BIOL. SOC. WASH. 94(3), 1981, pp. 902-947 KEY TO THE GENERA OF OCTOCORALLIA EXCLUSIVE OF PENNATULACEA (COELENTERATA: ANTHOZOA), WITH DIAGNOSES OF NEW TAXA Frederick M. Bayer Abstract.—A serial key to the genera of Octocorallia exclusive of the Pennatulacea is presented. New taxa introduced are Olindagorgia, new genus for Pseudopterogorgia marcgravii Bayer; Nicaule, new genus for N. crucifera, new species; and Lytreia, new genus for Thesea plana Deich- mann. Ideogorgia is proposed as a replacement ñame for Dendrogorgia Simpson, 1910, not Duchassaing, 1870, and Helicogorgia for Hicksonella Simpson, December 1910, not Nutting, May 1910. A revised classification is provided. Introduction The key presented here was an essential outgrowth of work on a general revisión of the octocoral fauna of the western part of the Atlantic Ocean. The far-reaching zoogeographical affinities of this fauna made it impossible in the course of this study to ignore genera from any part of the world, and it soon became clear that many of them require redefinition according to modern taxonomic standards. Therefore, the type-species of as many genera as possible have been examined, often on the basis of original type material, and a fully illustrated generic revisión is in course of preparation as an essential first stage in the redescription of western Atlantic species. The key prepared to accompany this generic review has now reached a stage that would benefit from a broader and more objective testing under practical conditions than is possible in one laboratory. For this reason, and in order to make the results of this long-term study available, even in provisional form, not only to specialists but also to the growing number of ecologists, biochemists, and physiologists interested in octocorals, the key is now pre- sented in condensed form with minimal illustration. -

Preliminary Report on the Octocorals (Cnidaria: Anthozoa: Octocorallia) from the Ogasawara Islands

国立科博専報,(52), pp. 65–94 , 2018 年 3 月 28 日 Mem. Natl. Mus. Nat. Sci., Tokyo, (52), pp. 65–94, March 28, 2018 Preliminary Report on the Octocorals (Cnidaria: Anthozoa: Octocorallia) from the Ogasawara Islands Yukimitsu Imahara1* and Hiroshi Namikawa2 1Wakayama Laboratory, Biological Institute on Kuroshio, 300–11 Kire, Wakayama, Wakayama 640–0351, Japan *E-mail: [email protected] 2Showa Memorial Institute, National Museum of Nature and Science, 4–1–1 Amakubo, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305–0005, Japan Abstract. Approximately 400 octocoral specimens were collected from the Ogasawara Islands by SCUBA diving during 2013–2016 and by dredging surveys by the R/V Koyo of the Tokyo Met- ropolitan Ogasawara Fisheries Center in 2014 as part of the project “Biological Properties of Bio- diversity Hotspots in Japan” at the National Museum of Nature and Science. Here we report on 52 lots of these octocoral specimens that have been identified to 42 species thus far. The specimens include seven species of three genera in two families of Stolonifera, 25 species of ten genera in two families of Alcyoniina, one species of Scleraxonia, and nine species of four genera in three families of Pennatulacea. Among them, three species of Stolonifera: Clavularia cf. durum Hick- son, C. cf. margaritiferae Thomson & Henderson and C. cf. repens Thomson & Henderson, and five species of Alcyoniina: Lobophytum variatum Tixier-Durivault, L. cf. mirabile Tixier- Durivault, Lohowia koosi Alderslade, Sarcophyton cf. boletiforme Tixier-Durivault and Sinularia linnei Ofwegen, are new to Japan. In particular, Lohowia koosi is the first discovery since the orig- inal description from the east coast of Australia. -

Checklist of Fish and Invertebrates Listed in the CITES Appendices

JOINTS NATURE \=^ CONSERVATION COMMITTEE Checklist of fish and mvertebrates Usted in the CITES appendices JNCC REPORT (SSN0963-«OStl JOINT NATURE CONSERVATION COMMITTEE Report distribution Report Number: No. 238 Contract Number/JNCC project number: F7 1-12-332 Date received: 9 June 1995 Report tide: Checklist of fish and invertebrates listed in the CITES appendices Contract tide: Revised Checklists of CITES species database Contractor: World Conservation Monitoring Centre 219 Huntingdon Road, Cambridge, CB3 ODL Comments: A further fish and invertebrate edition in the Checklist series begun by NCC in 1979, revised and brought up to date with current CITES listings Restrictions: Distribution: JNCC report collection 2 copies Nature Conservancy Council for England, HQ, Library 1 copy Scottish Natural Heritage, HQ, Library 1 copy Countryside Council for Wales, HQ, Library 1 copy A T Smail, Copyright Libraries Agent, 100 Euston Road, London, NWl 2HQ 5 copies British Library, Legal Deposit Office, Boston Spa, Wetherby, West Yorkshire, LS23 7BQ 1 copy Chadwick-Healey Ltd, Cambridge Place, Cambridge, CB2 INR 1 copy BIOSIS UK, Garforth House, 54 Michlegate, York, YOl ILF 1 copy CITES Management and Scientific Authorities of EC Member States total 30 copies CITES Authorities, UK Dependencies total 13 copies CITES Secretariat 5 copies CITES Animals Committee chairman 1 copy European Commission DG Xl/D/2 1 copy World Conservation Monitoring Centre 20 copies TRAFFIC International 5 copies Animal Quarantine Station, Heathrow 1 copy Department of the Environment (GWD) 5 copies Foreign & Commonwealth Office (ESED) 1 copy HM Customs & Excise 3 copies M Bradley Taylor (ACPO) 1 copy ^\(\\ Joint Nature Conservation Committee Report No. -

Susquhanna River Fishing Brochure

Fishing the Susquehanna River The Susquehanna Trophy-sized muskellunge (stocked by Pennsylvania) and hybrid tiger muskellunge The Susquehanna River flows through (stocked by New York until 2007) are Chenango, Broome, and Tioga counties for commonly caught in the river between nearly 86 miles, through both rural and urban Binghamton and Waverly. Local hot spots environments. Anglers can find a variety of fish include the Chenango River mouth, Murphy’s throughout the river. Island, Grippen Park, Hiawatha Island, the The Susquehanna River once supported large Smallmouth bass and walleye are the two Owego Creek mouth, and Baileys Eddy (near numbers of migratory fish, like the American gamefish most often pursued by anglers in Barton) shad. These stocks have been severely impacted Fishing the the Susquehanna River, but the river also Many anglers find that the most enjoyable by human activities, especially dam building. Susquehanna River supports thriving populations of northern pike, and productive way to fish the Susquehanna is The Susquehanna River Anadromous Fish Res- muskellunge, tiger muskellunge, channel catfish, by floating in a canoe or small boat. Using this rock bass, crappie, yellow perch, bullheads, and method, anglers drift cautiously towards their toration Cooperative (SRFARC) is an organiza- sunfish. preferred fishing spot, while casting ahead tion comprised of fishery agencies from three of the boat using the lures or bait mentioned basin states, the Susquehanna River Commission Tips and Hot Spots above. In many of the deep pool areas of the (SRBC), and the federal government working Susquehanna, trolling with deep running lures together to restore self-sustaining anadromous Fishing at the head or tail ends of pools is the is also effective. -

Annotated Check List of New Caledonian Soft Corals Leen P

Annotated check list of New Caledonian soft corals Leen P. van OFWEGEN National museum ofnatural History, Leiden, The Netherlands [email protected] The knowledge of the New Caledonian shallow-water soft coral fauna is mainly based on the work of Tixier-Durivault (1970) and Verseve1dt (1974), small additions were made by Alderslade (1994) and Ofwegen (2001). The below check list is essentially the list Tixier-Durivault published, and con sists of 173 species of soft corals in 20 genera, and 8 species of sea pens in 3 genera. The list must be considered somewhat doubtful as nowadays many of Tixier-durivault's identifications are chal lenged and a re-examination of the complete collection is necessary to get certainty about her identi fications. Still very little is known about octocoral biogeography, the only somewhat comparable study is Ofwegen (1996), in which 105 species of soft corals have been listed from the Bismarck Sea. These data suggest New Caledonia to be a much richer area, however, the Bismarck Sea material was col lected in only three localities, Laing Island, Boesa Island, and Madang. Ofwegen (2002) compared the distribution of all Indo-Pacific Sinularia species, New Caledonia was among the richest areas, only the Red Sea, the Seychelles-Mauritius Plateau, and eastern Africa had more species. But as already stated in that paper, those findings mostly reflected collection efforts. Similarly, because of lack of comparable studies, also little can be said about the level of endemism. 1 The species was described by Tixier-Durivault, 1970, as Alcyonium catalai. From the description it seems to be a species of Eleutherobia. -

Chaceon Fenneri) Off the Northern Coast of Brazil

Lat. Am. J. Aquat. Res., 37(3): 571-576, 2009 Golden crab fisheries off northeast Brazil 571 “Deep-sea fisheries off Latin America” P. Arana, J.A.A. Perez & P.R. Pezzuto (eds.) DOI: 10.3856/vol37-issue3-fulltext-21 Short Communication Note on the fisheries and biology of the golden crab (Chaceon fenneri) off the northern coast of Brazil Tiago Barros Carvalho1, Ronaldo Ruy de Oliveira Filho1 & Tito Monteiro da Cruz Lotufo1 1Laboratório de Ecologia Animal, Instituto de Ciências do Mar (LABOMAR) Universidade Federal do Ceará, Av. Abolição 3207, CEP 60165-081, Fortaleza, CE, Brazil ABSTRACT. The occurrence of golden crabs (Chaceon fenneri) off the northern coast of Brazil was first re- ported in 2001. Since then, a few companies and boats have exploited this resource. In the state of Ceará, one company has been fishing for these crabs with a single boat since 2003. The production and fishing effort of this company indicated a decrease in the number of trips and total catches per year. Data collected on one trip in 2006 showed that the CPUE was highest at over 650 m depth. As registered for other geryonid crabs, C. fenneri was segregated by sex along the northern slope of Brazil. Male crabs were significantly larger than fe- males, presenting an isometric relationship between carapace width and length and an allometric relationship between carapace width and body weight. Keywords: biology, fishery, Chaceon fenneri, golden crab, Geryonidae, Brazil. Nota sobre la biología y la pesca del cangrejo dorado (Chaceon fenneri) frente a la costa norte de Brasil RESUMEN. La presencia de cangrejos dorados (Chaceon fenneri) frente a la costa norte de Brasil fue prime- ramente descrita en 2001. -

Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge

Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive Conservation Plan U.S. Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region August 2008 COMPREHENSIVE CONSERVATION PLAN MERRITT ISLAND NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE Brevard and Volusia Counties, Florida U.S. Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Atlanta, Georgia August 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS COMPREHENSIVE CONSERVATION PLAN EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................... 1 I. BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 3 Purpose and Need for the Plan .................................................................................................... 3 U.S. Fish And Wildlife Service ...................................................................................................... 4 National Wildlife Refuge System .................................................................................................. 4 Legal Policy Context ..................................................................................................................... 5 National Conservation Plans and Initiatives .................................................................................6 Relationship to State Partners ..................................................................................................... -

The Growth History of a Shallow Inshore Lophelia Pertusa Reef

Growth of North-East Atlantic Cold-Water Coral Reefs and Mounds during the Holocene: A High Resolution U-Series and 14C Chronology Mélanie Douarin1, Mary Elliot1, Stephen R. Noble2, Daniel Sinclair3, Lea- Anne Henry4, David Long5, Steven G. Moreton6,J. Murray Roberts4,7,8 1: School of Geosciences, The University of Edinburgh, Grant Institute, The King’s Buildings, West Mains Road, Edinburgh, Scotland, EH9 3JW, UK; [email protected] 2: NERC Isotope Geosciences Laboratory, British Geological Survey, Keyworth, Nottingham, England, NG12 5GG, UK 3: Marine Biogeochemistry & Paleoceanography Group, Institute of Marine and Coastal Sciences, Rutgers University, 71 Dudley Road, New Brunswick, NJ 08901-8525, USA 4: Centre for Marine Biodiversity & Biotechnology, School of Life Sciences, Heriot- Watt University, Edinburgh, Scotland, EH14 4AS, UK 5: British Geological Survey, West Mains Road, Edinburgh, Scotland, EH9 3LA, UK 6: NERC Radiocarbon Facility (Environment), Scottish Enterprise Technology Park, Rankine Avenue, East Kilbride, Glasgow, Scotland, G75 0QF, UK 7: Scottish Association for Marine Science, Scottish Marine Institute, Oban, Argyll, PA37 1QA, UK 8: Center for Marine Science, University of North Carolina Wilmington, 601 S. College Road, Wilmington, NC 28403-5928, USA 1. Abstract We investigate the Holocene growth history of the Mingulay Reef Complex, a seascape of inshore cold-water coral reefs off western Scotland, using U-series dating of 34 downcore and radiocarbon dating of 21 superficial corals. Both chronologies reveal that the reef framework-forming scleractinian coral Lophelia pertusa shows episodic occurrence during the late Holocene. Downcore U-series dating revealed unprecedented reef growth rates of up to 12 mm a-1 with a mean rate of 3 – 4 mm a-1. -

Deep‐Sea Coral Taxa in the U.S. Gulf of Mexico: Depth and Geographical Distribution

Deep‐Sea Coral Taxa in the U.S. Gulf of Mexico: Depth and Geographical Distribution by Peter J. Etnoyer1 and Stephen D. Cairns2 1. NOAA Center for Coastal Monitoring and Assessment, National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science, Charleston, SC 2. National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC This annex to the U.S. Gulf of Mexico chapter in “The State of Deep‐Sea Coral Ecosystems of the United States” provides a list of deep‐sea coral taxa in the Phylum Cnidaria, Classes Anthozoa and Hydrozoa, known to occur in the waters of the Gulf of Mexico (Figure 1). Deep‐sea corals are defined as azooxanthellate, heterotrophic coral species occurring in waters 50 m deep or more. Details are provided on the vertical and geographic extent of each species (Table 1). This list is adapted from species lists presented in ʺBiodiversity of the Gulf of Mexicoʺ (Felder & Camp 2009), which inventoried species found throughout the entire Gulf of Mexico including areas outside U.S. waters. Taxonomic names are generally those currently accepted in the World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS), and are arranged by order, and alphabetically within order by suborder (if applicable), family, genus, and species. Data sources (references) listed are those principally used to establish geographic and depth distribution. Only those species found within the U.S. Gulf of Mexico Exclusive Economic Zone are presented here. Information from recent studies that have expanded the known range of species into the U.S. Gulf of Mexico have been included. The total number of species of deep‐sea corals documented for the U.S. -

Annotated Bibliography of Fishing Impacts on Habitat - September 2003 Update

ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY OF FISHING IMPACTS ON HABITAT - SEPTEMBER 2003 UPDATE Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission SEPTEMBER 2003 GSMFC No.: 115 Annotated Bibliography of Fishing Impacts on Habitat - September 2003 Update Edited by Jeffrey K. Rester Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission September 2003 Introduction This is the third in a series of updates to the Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission’s Annotated Bibliography of Fishing Impacts on Habitat originally produced in February 2000. The Commission’s Habitat Subcommittee felt that the gathering of pertinent literature should continue. The third update contains 52 new articles since the publication of the last update. The update uses the same criteria that the original bibliography and first and second updates used to compile articles. It attempts to compile a listing of papers and reports that address the many effects and impacts that fishing can have on habitat and the marine environment. The bibliography is not limited to scientific literature only. It includes technical reports, state and federal agency reports, college theses, conference and meeting proceedings, popular articles, and other forms of nonscientific literature. This was done in an attempt to gather as much information on fishing impacts as possible. Researchers will be able to decide for themselves whether they feel the included information is valuable. Fishing, both recreational and commercial, can have many varying impacts on habitat and the marine environment. Whether a fisher prop scars seagrass, drops an anchor on a coral reef, or drags a trawl across the bottom, each act can alter habitat and affect fish populations.