Marital Policy and the Role of Flanders in the Colonisation of Madeira and the Azores

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Portugal's Hidden

The Azores Portugal ’s hidden gem AUGUST 5-13, 2021 $ The 400 COUPLE SavePER Book by Azores JANUARY 31, 2021 Dear Vanderbilt Traveler, Portugal ’s hidden gem You are invited to discover the exotic natural wonders of the Azores, Portugal’s hidden gem! We are pleased to announce a very special alumni trip to this cutting-edge travel destination scheduled for August 2021. One of two autonomous regions of Portugal, this archipelago is composed of nine volcanic islands in the Macaronesia region of the North Atlantic Ocean. Situated 930 miles directly west of Lisbon, this lush and untamed archipelago offers visitors an unexplored paradise replete with natural and culinary treasures. On the island of Pico, see the beauty of Arcos do Cachorro, Mistério de São João, and Fajã dos Vimes. Learn about the island’s fascinating natural history at Gruta das Torres, the largest lava tube in the Azores. Continue to the island of São Miguel and experience its breathtaking beauty at Sete Cidades, Terra Nostra Park, Fogo Lake, and the hot springs of Furnas. As stunning as the Azores geography can be, their cuisine is equally rewarding. Please your palette during a private visit to a local winery and cheese factory in Ponta dos Rosais. From the famous cozido to the local pastries and tea plantations, savor the wide range of Azorean tastes and traditions. Space on this program is strictly limited. Contact us as soon as possible to reserve your place. We look forward to having you join us on this remarkable adventure. Sincerely, Cary DeWitt Allyn For more details: WWW.VUCONNECT.COM/TRAVEL Director, Vanderbilt Travel Program 615.322.3673 AUGUST 5-13, 2021 THURSDAY, AUGUST 5: DEPART USA ALDEIA DA FONTE NATURE HOTEL Depart USA on your overnight flight(s) to Ponta Delgada, Azores. -

Recent Acquisitions: a Rare Work by Jacobus Tevius Barry Taylor

Recent Acquisitions: a Rare Work by Jacobus Tevius Barry Taylor The British Library has recently had the good fortune to buy a rare work by a major figure in Portuguese Renaissance Humanism. Its description is as follows: Iacobi Tevii Lusitani. Epodon siue Ia(m)bicorum carminum libri tres [...] Ad Sebastianum primum, inuictissimum Lusitaniæ Regem (Lisbon: Francisco Correia, 1565) 12º. [6], 171 [sic for 160], [2], 66 leaves.1 British Library pressmark: RB.23.a.23815 The work is divided into three books: 1. Sententiarum vtilium quidem omnibus hominibus, sed regibus ac rerum moderatoribus præcipue, quibus addita est boni principis institutio. 2. Hymnorum ad Iesum Christum & ad diuos huiusce regni patronos pro Regis salute & rerum felicissimo statu. 3. De perfecto Episcopo & alia opuscula ad Henricum Serenissimum principem, cardinalemque illustrissimum regnique moderatorem sapientissimum. The author, Diogo de Teive, wrote only under the Latin form of his name, Jacobus Te vius.2 He was born in Braga between 1513 and 1515, and died between 1565 and 1579, probably in Lisbon. His career displays both the glory of Portuguese Humanism and its decline under the Inquisition. Like many a scholar of his generation,Tevius was a traveller, a situation aided by the international currency of Latin. From the age of twelve he studied at the Collège de Sainte-Barbe in Paris, under a Portuguese mentor, Diogo de Gouveia Senior. From 1532 to 1534 he taught at Salamanca. Finding the Spanish university town did not provide him with the peace and quiet necessary for study, he returned to France, studying law at Toulouse and teaching at Bordeaux, where he held a chair in Humanities. -

Pietas Austriaca at the Lisbon Court

THEHABSBURGSANDTHEIRCOURTSINEUROPE,1400–1700.BETWEENCOSMOPOLITISMANDREGIONALISM PietasAustriacaattheLisbonCourt TheMonumentalChapelandFuneraryTombsbuiltbyCatherineofAustria intheSanJerónimosMonasticComplexinBelém AnnemarieJordanGschwendȋ ×±ǦǡȌ Prologue In1570,atacrucialstageinherlifeandreign,CatherineofAustria(1507Ͳ1578),QueenofPortugal, decided to retire from politics and government.1 She sought official permission from court and church officials to leave Portugal and return to her native country of Spain, where she hoped to reside in a convent, living out the remaining years of her life in prayer and meditation. Although Catherinewasinspiredbyearlierprecedencediscussedbelow,shewasalsotroubledbyintriguesat theLisboncourt.By1570,afterhavingbeenpredeceasedbyherbelovedhusbandJohnIIIandher ninechildren,thequeenwasreadytoliveouttherestofherlifeinsolitude. In 1498 the Dowager Queen Leonor of Portugal (1458Ͳ1525) had founded a new confraternity in Portugal dedicated to the Virgin of Mercy (Virgem da Misericordia), the primary purposeofwhichwastoassisttheindigent,illandvagabond,ransomcaptivesoftheMoors,shelter orphans,runhospitalsandhospices,promoteworksofcharity,andbuildconventsandchurches.2 Leonor, who earned a reputation in Portugal, as the ‘Perfect Queen’ (Rainha Perfeita), was celebratedbyhersubjectsforherChristianvirtues,charityandculturalpatronage.TheMadrede Deus convent of Franciscan nuns with its church in Xabregas on the city outskirts of Lisbon was foundedandbuiltbyLeonorin1519tohousetherelicsofSaintAutaandthe11,000VirginMartyrs -

Judaeo-Converso Merchants in the Private Trade Between Macao and Manila in the Early Modern Period

JUDAEO-CONVERSO MERCHANTS IN THE PRIVATE TRADE BETWEEN MACAO AND MANILA IN THE EARLY MODERN PERIOD LÚCIO DE SOUSA Tokyo University of Foreign Studiesa ABSTRACT The present paper intends to contribute with new information to a reconstruction of the Sephardic presence in the Macao–Manila commer- cial network. For this purpose, in the first place, we intend to trace the pro- file of the Judaeo-converso merchants arriving in China and the Philippines and to reconstruct the commercial networks to which they belonged during the 16th and early 17th centuries. Keywords: Jewish Diaspora, commercial networks, Macao–Manila JEL Codes: N15, N16 RESUMEN El presente artículo tiene la intención de contribuircon información nueva a una reconstrucción de la presencia sefardí en la red comercial Macao– Manila. Para este fin, el trabajo rastrea el perfil de los comerciantes Judaeo- conversos que viven en China y Filipinas y reconstruye las redes comerciales a las que pertenecieron durante el siglo XVI y principios del siglo XVII. Palabras clave: Diáspora judía, redes comerciales, Macao-Manila a School of International and Area Studies, Tokyo University of Foreign Studies, Fuchu, Tokyo 183-8534, Japan. [email protected] Revista de Historia Económica, Journal of Iberian and Latin American Economic History 519 Vol. 38, No. 3: 519–552. doi:10.1017/S0212610919000260 © Instituto Figuerola, Universidad Carlos III de Madrid 2019. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. -

Checklists of Crustacea Decapoda from the Canary and Cape Verde Islands, with an Assessment of Macaronesian and Cape Verde Biogeographic Marine Ecoregions

Zootaxa 4413 (3): 401–448 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) http://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2018 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4413.3.1 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:2DF9255A-7C42-42DA-9F48-2BAA6DCEED7E Checklists of Crustacea Decapoda from the Canary and Cape Verde Islands, with an assessment of Macaronesian and Cape Verde biogeographic marine ecoregions JOSÉ A. GONZÁLEZ University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, i-UNAT, Campus de Tafira, 35017 Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain. E-mail: [email protected]. ORCID iD: 0000-0001-8584-6731. Abstract The complete list of Canarian marine decapods (last update by González & Quiles 2003, popular book) currently com- prises 374 species/subspecies, grouped in 198 genera and 82 families; whereas the Cape Verdean marine decapods (now fully listed for the first time) are represented by 343 species/subspecies with 201 genera and 80 families. Due to changing environmental conditions, in the last decades many subtropical/tropical taxa have reached the coasts of the Canary Islands. Comparing the carcinofaunal composition and their biogeographic components between the Canary and Cape Verde ar- chipelagos would aid in: validating the appropriateness in separating both archipelagos into different ecoregions (Spalding et al. 2007), and understanding faunal movements between areas of benthic habitat. The consistency of both ecoregions is here compared and validated by assembling their decapod crustacean checklists, analysing their taxa composition, gath- ering their bathymetric data, and comparing their biogeographic patterns. Four main evidences (i.e. different taxa; diver- gent taxa composition; different composition of biogeographic patterns; different endemicity rates) support that separation, especially in coastal benthic decapods; and these parametres combined would be used as a valuable tool at comparing biotas from oceanic archipelagos. -

Post-Glacial Filling of a Semi-Enclosed Basin: the Arguin Basin (Mauritania)

Marine Geology 349 (2014) 126–135 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Marine Geology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/margeo Post-glacial filling of a semi-enclosed basin: The Arguin Basin (Mauritania) N. Aleman a,⁎,R.Certaina,J.P.Barusseaua,T.Courpa,A.Diab a Centre Européen de Formation et de Recherche sur les Environnements Méditerranéens, UMR5110, Université de Perpignan, 52 av. P Alduy, 66860 Perpignan, France b Institut Mauritanienne de Recherche Océanographique et des Pêches, BP22, Nouadhibou, Mauritania article info abstract Article history: Semi-enclosed basins are not very common features in the world and are most frequently the result of tectonic Received 31 January 2013 movements. Studies of their filling are usually based on the micropaleontological analyses of sediment cores Received in revised form 11 December 2013 (Torgersen et al., 1988; Reeves et al., 2007) or seismic analyses (Lykousis et al., 2007; Çagatay et al., 2009; Van Accepted 24 December 2013 Daele et al., 2011). The morphology of semi-enclosed basins is generally simple and bowl-shaped, and their Available online 2 January 2014 edges are marked by one or more sills. Their depths range from a few dozen to several thousand meters. Semi- Communicated by J.T. Wells enclosed basins are however present in some regions in the world. The semi-enclosed basin of the Golfe d'Arguin (Northwest Africa) is present on a wide, shallow shelf, bordering the Sahara desert, in a stable tectonic context. Its Keywords: sedimentary filling took place during the end of the post-glacial transgression. The current knowledge on sedi- semi-enclosed basin mentary filling of semi-enclosed basins is rather limited and inadequate to fully understand the processes at play. -

The Best of the Azores

The Best of the Azores 11 October to 21 October, 2017 $2,799 Per Person…based on double occupancy. Includes taxes of approximately 160 USD. 9 Nights with breakfast daily in Terceira, Faial, and Sao Miguel. 16 Meals, including welcome and farewell dinner. Private Tours: Terceira Island Tour, Faial Island Tour, Pico Island Tour with ferry, Sete Cidades Tour, Furnas Tour (with Cozido) ,all private tours include transfers and English Speaking Guide. Airfare included from Boston to Terceira, return from Sao Miguel to Boston as well as internal flights within the Azores. Includes Round-Trip Transfer from New Bedford to Boston Logan Airport. 761 Bedford Street, Fall River, MA 02723 www.sagresvacations.com Ph#508-679-0053 Your Itinerary Includes Hotels Angra do Heroismo, Terceira Island o Angra Garden Hotel Check in 12OCT-14OCT o Double Room with breakfast daily Horta, Faial Island o Faial Resort Hotel Check in 14OCT-16OCT o Double room with breakfast daily Ponta Delgada, Sao Miguel Island o Royal Garden Hotel Check in 16OCT-21OCT Double Room with breakfast daily Private Transfers Airport Transfers Included o New Bedford to Boston Logan Airport transfers round-trip 11OCT-21 OCT o TER Airport to Angra Garden Hotel and vice-versa 12OCT-14OCT o Horta Airport to Faial Resort Hotel and vice-versa 14OCT-16OCT. o P. Delgada Airport to Royal Garden Hotel and vice-versa Terceira 16OCT-21OCT. All Transfers included on Private Tours Private Tours/Excursions Terceira o Full Day Terceira Tour with Lunch. Faial o Full Day Faial Tour with Lunch o Pico -

Secret Base: Santa Maria Airfield During World War II

vol.3 | Dezembro 2017 | Revista LPAZ vol.3 | Dezembro 2017 | Revista LPAZ September. At first base personnel were mostly civilian activated on August 1, 1944, with assignment to the North Secret Base: workers from two construction companies: W. C. Shepard Atlantic Division of the Air Transport Command. of Atlanta, Georgia, and W. A. Hart of Fort Lauderdale, Santa Maria Airfield during World War II Florida. Records show that during the opening phase, Keeping the military nature of the base secret was difficult. there were 267 civilians, 11 officers, and 124 enlisted Mail and baggage was inspected, with strict censorship of Daniel Haulman men, about half of them members of the 786th Military as many as 800 letters a day. Portuguese natives were Air Force Historical Research Agency | USA Police Detachment. Lt. Col. Russell W. Gray commanded not fooled when they saw American military personnel the temporary camp, with 45 pyramidal tents for military wearing khaki shirts showing marks where chevrons and During World War II, many European nations remained occupied France. In August, free French and American personnel. Nine other tents sheltered administrative insignia had been. Many of the American civilian workers neutral in the struggle between the Axis countries, led by forces invaded southern France, where German forces offices, mess facilities, and supplies. Civilian workers became discipline problems, partly because they had not Germany, Italy, and Japan, and the Allies, led by Britain, were forced to retreat, and Allied forces entered Paris by lived in similar temporary shelters, at first. By the end been carefully selected, and partly because they were the Soviet Union, and the United States. -

GPS AZORES Project

GPS AZORES Project Title: Geopolitical framework of the Macaronesia region Project Coordinator: Helena Calado (Universidade dos Azores) Work Package Coordinator: Juan Luis Suarez de Vivero (Universidad de Sevilla) Authors: Elisabetta Menini, Firdaous Halim, Daniela Gabriel, Juan Luis Suarez de Vivero, Helena Calado, Fabiana Moniz, Mario Caña Varona. Submission date: 31 August 2018 Acknowledgements: Christine Ladiero for helping with statistics Citation: Menini E., Halim F., Gabriel, D., Suarez de Vivero, JL., Calado, H., Moniz, F., Caña Varona, M. 2018. Geopolitical framework of the Macaronesia region. GPS Azores project: Ponta Delgada. Page 1 This project was financed in 85% by FEDER and in 15% with regional funds through the Programa Operacional Açores 2020 (Operational Program Azores 2020), in scope of the project « GPSAZORES -ACORES-01-0145-FEDER-00002». Page 2 Contents ACRONYMS 4 1. Maritime scenario characterisation: Main political, jurisdictional and socio-economic features 5 1.1 Political geography of the region 5 1.1.1 The regional context: Macaronesia 5 1.1.2 Countries and territories 12 1.2 Maritime space 16 1.2.1 Macaronesia in the context of the United Nations Convention of the Law of the Sea 16 1.2.2 Maritime jurisdictions 19 1.2.3 Maritime borders 21 1.3 The socio-economic context: exploitation and uses of the maritime space 26 1.3.1 Demography 26 1.3.2 Economic development 27 1.3.3 Tourism 29 1.3.1 Fisheries and aquaculture 31 1.3.2 Regional maritime geo-economics 33 1.3.3 Other relevant maritime economic activities 33 -

The Portrait of Juana of Austria in the Bilbao Fine Arts Museum

IN THE KING’S NAME The Portrait of Juana of Austria in the Bilbao Fine Arts Museum Leticia Ruiz Gómez This text is published under an international Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs Creative Commons licence (BY-NC-ND), version 4.0. It may therefore be circulated, copied and reproduced (with no alteration to the contents), but for educational and research purposes only and always citing its author and provenance. It may not be used commercially. View the terms and conditions of this licence at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-ncnd/4.0/legalcode Using and copying images are prohibited unless expressly authorised by the owners of the photographs and/or copyright of the works. © of the texts: Bilboko Arte Ederren Museoa Fundazioa-Fundación Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao Photography credits © Bilboko Arte Ederren Museoa Fundazioa-Fundación Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao: fig. 1 © Kunsthistorisches Museum, Wien: fig. 7 © Musées Royaux des Beaux Arts de Belgique, Bruxelles: fig. 4 © Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid: figs. 2, 3, 5, 9 and 10 © Patrimonio Nacional, Madrid: figs. 6 and 8 Text published in: B’06 : Buletina = Boletín = Bulletin. Bilbao : Bilboko Arte Eder Museoa = Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao = Bilbao Fine Arts Museum, no. 2, 2007, pp. 85-123. Sponsored by: 2 n the 1550s Princess Juana of Portugal was a regular subject for portrait artists, being one of the leading women in the House of Austria, the dynasty that dominated the political scene in Europe throughout the I16th century. The youngest daughter of Charles V and Isabella of Portugal, she had a special role to play in her father’s geopolitical strategies, first as the wife of the heir to the Portuguese throne, to whom she bore a posthumous son who would eventually come to the throne of Spain’s neighbour, and subsequently as regent of the Emperor’s peninsular territories. -

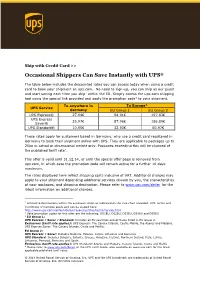

Occasional Shippers Can Save Instantly with UPS®

Ship with Credit Card >> Occasional Shippers Can Save Instantly with UPS® The table below includes the discounted rates you can access today when using a credit card to book your shipment on ups.com. No need to sign-up, you can ship as our guest and start saving each time you ship1 within the EU. Simply access the ups.com shipping tool using the special link provided and apply the promotion code2 to your shipment. To anywhere in To Europe3 UPS Service Germany EU Group 1 EU Group 2 UPS Express® 27.94€ 94.01€ 197.83€ UPS Express 25.97€ 87.96€ 186.89€ Saver® UPS Standard® 10.95€ 32.93€ 50.97€ These rates apply for customers based in Germany, who use a credit card registered in Germany to book their shipment online with UPS. They are applicable to packages up to 20kg in actual or dimensional weight only. Packages exceeding this will be charged at the published tariff rate4. This offer is valid until 31.12.14, or until the special offer page is removed from ups.com, in which case the promotion code will remain active for a further 10 days maximum. The rates displayed here reflect shipping costs inclusive of VAT. Additional charges may apply to your shipment depending additional services chosen by you, the characteristics of your packages, and shipping destination. Please refer to www.ups.com/de/en for the latest information on additional charges. 1 Limited to destinations within the European Union as indicated on the rate chart provided. UPS Terms and Conditions of Carriage apply and can be viewed here: http://www.ups.com/content/de/en/resources/ship/terms/service.html 2 Valid promotion codes for this offer are the following: DE1EU, DE2EU, DE3EU, DE4EU and DE5EU 3 EU Group 1: UPS Express / Saver / Standard: Includes all EU countries except those listed in EU Group 2. -

Santa Maria Island's (Azores Archipelago) Geological Evolution: New Insights from High-Resolution Marine Geophysical Data

Geophysical Research Abstracts Vol. 20, EGU2018-2422, 2018 EGU General Assembly 2018 © Author(s) 2017. CC Attribution 4.0 license. Santa Maria Island’s (Azores Archipelago) geological evolution: new insights from high-resolution marine geophysical data. Alessandro Ricchi (1), Rui Quartau (2,3), Ricardo Ramalho (4,5), Claudia Romagnoli (1), Daniele Casalbore (6,7) (1) University of Bologna, BiGeA, Italy ([email protected]), (2) Instituto Dom Luiz, Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade de Lisboa, 1749-016 Lisboa, Portugal, (3) Divisão de Geologia Marinha, Instituto Hidrográfico – Marinha, 1200-615 Lisboa, Portugal, (4) School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, BS8 1RJ Bristol, UK, (5) Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory at Columbia University, 10964 New York, USA, (6) Sapienza Università di Roma, Dipartimento Scienze della Terra, Roma, Italy, (7) Istituto di Geologia Ambientale e Geoingegneria, Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, Area della Ricerca Roma 1, Montelibretti, Via Salaria Km 29,300, Monterotondo, Roma, Italy Santa Maria is the oldest island of the Azores Archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, having first emerged at c.6 Ma (Ramalho et al., 2017). Its geological evolution up to now was constrained only by the knowledge of the subaerial volcanic edifice, since the submerged portion of the island has never been studied. In this work we used high-resolution multibeam bathymetry and closely-spaced seismic reflection profiles to study the morpho-stratigraphic setting of Santa Maria’s insular shelf. In particular the shelf width and the depth of its edge where used as proxies for reconstructing the development of the earlier portions of Santa Maria Island. Our study suggests that the large insular shelf off the northern coast of Santa Maria is the remnant of an early, now almost completely razed, volcanic edifice likely older than the volcanic sequences exposed onland.