Secondary Education in Oecd Countries Common Challenges, Differing Solutions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of Adult and Continuing Education

History of Adult and Continuing Education The Adult and Continuing Education function has been central to the mission of the college since its founding in 1966. Originally it was one of three major college focal points along with vocational-technical education and student services. The department’s mission is consistent with several of the directives in SF550, the law that created the community college system in Iowa in 1966: Programs for in-service training and retraining of workers; Developmental education for persons academically or personally underprepared to succeed in their program of study; Programs for training, retraining, and preparation for productive employment of all citizens; and Programs for high school completion for students of post-high school age. The 1968 North Central Association Self Study prepared constructive notes as a first step toward regional accreditation on these major functions of the department: Adult and Continuing Education provided educational programs in four areas: adult basic education, adult high school diploma programs, high school equivalency programs, and general adult education. Adult basic education programs developed throughout the area provided instruction to adults with less than an eighth grade education. Adult high school diploma programs provided instruction to adults with a 10th grade education but less than a high school education. Students enrolled in these programs were working toward the completion of a high school program and the receipt of a diploma from an established secondary school within the area. High school equivalency programs provided instruction to students who had completed at least eighth grade, and by completing additional course work, could be granted a high school equivalency certificate by the Iowa State Department of Public Instruction. -

EDUCATION in CHINA a Snapshot This Work Is Published Under the Responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD

EDUCATION IN CHINA A Snapshot This work is published under the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of OECD member countries. This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. Photo credits: Cover: © EQRoy / Shutterstock.com; © iStock.com/iPandastudio; © astudio / Shutterstock.com Inside: © iStock.com/iPandastudio; © li jianbing / Shutterstock.com; © tangxn / Shutterstock.com; © chuyuss / Shutterstock.com; © astudio / Shutterstock.com; © Frame China / Shutterstock.com © OECD 2016 You can copy, download or print OECD content for your own use, and you can include excerpts from OECD publications, databases and multimedia products in your own documents, presentations, blogs, websites and teaching materials, provided that suitable acknowledgement of OECD as source and copyright owner is given. All requests for public or commercial use and translation rights should be submitted to [email protected]. Requests for permission to photocopy portions of this material for public or commercial use shall be addressed directly to the Copyright Clearance Center (CCC) at [email protected] or the Centre français d’exploitation du droit de copie (CFC) at [email protected]. Education in China A SNAPSHOT Foreword In 2015, three economies in China participated in the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment, or PISA, for the first time: Beijing, a municipality, Jiangsu, a province on the eastern coast of the country, and Guangdong, a southern coastal province. -

Education Degree

CAREER OPPORTUNITIES BACHELOR Of SCIENCE G Early Childhood Education Grades P-3 G (also includes coursework for certification in G DUCATION elementary education grades K-6) G E Elementary Education Grades K-6 G Secondary Education Grades 6-12 G DEGREE • Biology/Biology Education G • Biology/General Science Education G • Chemistry/Chemistry Education G • English/English Language Arts Education G • History/ General Social Studies Education G • Mathematics/Mathematics Education G P-12 Education G • Music Education (Choral) G • Music Education (Instrumental) G Child Development G (Non teacher certification program) G Graduates Seek Careers in: G • Hospitals G • Residential Programs G • Childcare Centers G • Head Start Programs G IVISION Of DUCATION G • Children’s Museums D E • State Agencies P.O. Box 39800 G Birmingham, AL 35208 G G G G G Please call for additional information G G Phone: 205-929-1695 G G www.miles.edu G G G G G G G G Miles College is accredited to award G G Bachelors degrees by the Commission on G G Colleges of the Southern Association of G G Colleges and Schools: 1866 Southern Lane, G G Decatur, GA 30033-4097, G G Phone: 404-679-4501 G G G G G G G DIVISION Of G G EDUCATION G G WHY STUDY EDUCATION AT STUDENT ORGANIZATIONS INTERNSHIP/STUDENT TEACHING MILES COLLEGE? AND ACTIVITIES CLOAKING CEREMONY e Division of Education offers programs in All candidates in the Division of Education are Each semester teacher education majors who are teacher education that meet the Alabama encouraged to participate in student organizations. -

Secondary Education San Francisco State University Bulletin 2020-2021

Secondary Education San Francisco State University Bulletin 2020-2021 S ED 200 Introduction to Teaching and Education (Units: 3) SECONDARY EDUCATION Introduction to the field of education and to the profession of teaching. (Plus-minus letter grade only) Graduate College of Education Course Attributes: Dean: Dr. Cynthia Grutzik • D1: Social Sciences Department of Secondary Education S ED 300 Education and Society (Units: 3) Burk Hall, Room 45 Prerequisites: GE Areas A1*, A2*, A3*, and B4* all with grades of C- or (415) 338-1201/1202 better or consent of the instructor. Chair: Dr. Maika Watanabe Introduction to education and the role that education and schools play in Graduate Coordinator, Concentration in Secondary Education: Dr. Maika society. Watanabe Course Attributes: Graduate Coordinator, Concentration in Mathematics Education: Dr. Judith Kysh • UD-D: Social Sciences Professor • Social Justice YANAN FAN (2006), Professor of Secondary Education; B.A. (1992), Capital S ED 640 Supervised Observation and Participation in Public Schools Normal University, Beijing, China; M.A. (2000), Beijing Normal University, (Units: 3) Beijing, China; Ph.D. (2006), Michigan State University. Prerequisite: Concurrent enrollment in S ED 751. JUDITH KYSH (2000), Professor of Mathematics, Professor of Secondary A program of observation and participation in public schools under the Education; B.A. (1962), M.A. (1965), University of California, Berkeley; guidance of a university supervisor including regular meetings for the Ph.D. (1999), University of California, Davis. analysis of field experiences. (CR/NC grading only) [CSL may be available] Course Attributes: MAIKA WATANABE (2003), Professor of Secondary Education; B.A. (1995), Swarthmore College; M.A. (1999), Ph.D. -

Secondary School Course Classification System: School Codes for the Exchange of Data (SCED) (NCES 2007-341)

Secondary School Course Classification U.S. Department of Education NCES 2007-341 System: School Codes for the Exchange of Data (SCED) Secondary School Course Classification System: School U.S. Department of Education Codes for the NCES 2007-341 Exchange of Data (SCED) June 2007 Denise Bradby Rosio Pedroso MPR Associates, Inc. Andy Rogers Consultant Quality Information Partners Lee Hoffman Project Officer National Center for Education Statistics U.S. Department of Education Margaret Spellings Secretary Institute of Education Sciences Grover J. Whitehurst Director National Center for Education Statistics Mark Schneider Commissioner The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) is the primary federal entity for collecting, analyzing, and reporting data related to education in the United States and other nations. It fulfills a congressional mandate to collect, collate, analyze, and report full and complete statistics on the condition of education in the United States; conduct and publish reports and specialized analyses of the meaning and significance of such statistics; assist state and local education agencies in improving their statistical systems; and review and report on education activities in foreign countries. NCES activities are designed to address high-priority education data needs; provide consistent, reliable, complete, and accurate indicators of education status and trends; and report timely, useful, and high-quality data to the U.S. Department of Education, the Congress, the states, other education policymakers, practitioners, data users, and the general public. Unless specifically noted, all information contained herein is in the public domain. We strive to make our products available in a variety of formats and in language that is appropriate to a variety of audiences. -

Classifying Educational Programmes

Classifying Educational Programmes Manual for ISCED-97 Implementation in OECD Countries 1999 Edition ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT Foreword As the structure of educational systems varies widely between countries, a framework to collect and report data on educational programmes with a similar level of educational content is a clear prerequisite for the production of internationally comparable education statistics and indicators. In 1997, a revised International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED-97) was adopted by the UNESCO General Conference. This multi-dimensional framework has the potential to greatly improve the comparability of education statistics – as data collected under this framework will allow for the comparison of educational programmes with similar levels of educational content – and to better reflect complex educational pathways in the OECD indicators. The purpose of Classifying Educational Programmes: Manual for ISCED-97 Implementation in OECD Countries is to give clear guidance to OECD countries on how to implement the ISCED-97 framework in international data collections. First, this manual summarises the rationale for the revised ISCED framework, as well as the defining characteristics of the ISCED-97 levels and cross-classification categories for OECD countries, emphasising the criteria that define the boundaries between educational levels. The methodology for applying ISCED-97 in the national context that is described in this manual has been developed and agreed upon by the OECD/INES Technical Group, a working group on education statistics and indicators representing 29 OECD countries. The OECD Secretariat has also worked closely with both EUROSTAT and UNESCO to ensure that ISCED-97 will be implemented in a uniform manner across all countries. -

Continuing Education and Training After High School Customer Guide To

CCustomerustomer GGuideuide ttoo CContinuingontinuing EEducationducation aandnd TTrainingraining AAfterfter High School Introduction to Michigan Rehabilitation Services, Page 2. Eligibility for Michigan Rehabilitation Services, Page 3. Making the Transition, Page 4. Ten Ways Higher Education and Training Differs from High School, Page 5. An Overview of Laws—A Comparison of Rights and Responsibilities . .6 Thinking About Postsecondary Education?—Consider This . .7 Visiting Postsecondary Institutions. .8 Higher Education and Training Options—What Are They? . .9-10 Michigan Career and Technical Institute . .11 MRS Support Services for Continuing Education Leading to Employment. .12 Partnering with MRS—Student Responsibilities. .13 Combining Work Experience and Higher Education . .14 Role of Parents/Caregivers in Student Success . .15 Applying to Postsecondary Institutions . .16 Financial Aid Overview . .17 Disability Support Services (DSS) . .18 Preparing Student Disability Documentation . .19 Accessing Accommodations and Being Proactive about Learning—A Recipe for Success . .20 Student Planning Tools: Accommodations Planning Guide . .21 Study Skills and Learning Strategies Planning Guide . .22 Assistive Technology Guide. .23 Preparation Checklist. .24 Checklist for Success . .25 State of Michigan Student Aid . .26 Additional Resources . .27 Michigan Public College and University Contact Information . 28-30 Client Assistance Program (CAP) . .31 Glossary of Terms . 32-36 2 WELCOME TO Mission: Michigan Rehabilitation Services (MRS) partners with individuals and employers to achieve quality employment outcomes and independence for individuals with disabilities. High school students are often referred to MRS by special education teachers as they transition from secondary education to postsecondary education and employment. When students participate with MRS they are assigned to a rehabilitation counselor who assists them through the rehabilitation process. -

Transforming Secondary Education in Pakistan Using Flipped Classrooms

Transforming Secondary Education in Pakistan Using Flipped Classrooms EDKASA (pronounced ed-kasa) leverages rapid speed of internet penetration in Pakistan to make quality teachers accessible for secondary education. Using a flipped classroom model, EDKASA plans to deploy 500 franchises to distribute its ‘live teaching web-streams’ reaching 20,000 secondary students by 2020. The Challenge Improving secondary education outcomes has a direct impact on poverty reduction. UNESCO reports that the global poverty rate can be halved if all adults completed secondary education1. Pakistan has more than 15 million out of school secondary students1. A major reason for this is insufficient number of secondary schools – only 1 in 9 government schools is a secondary school2. In addition, of those who do attend secondary schools, more than half do not graduate1. The widespread availability of internet in Pakistan can potentially transform secondary education outcomes. 90% of the population will have access to 3G/4G internet by 20203. However, ownership of internet enabled devices is expected to significantly lag behind due to low disposable income. Hence, any education delivery solution that wants to leverage internet needs to be designed for a low-resource setting. The EDKASA Solution EDKASA is an edtech startup based in Lahore, Pakistan that connects students with ‘Rock Star’ teachers using its live, interactive virtual classroom platform. EDKASA wants to expand into the secondary education segment using a franchise-based model that makes EDKASA’s live web-streams accessible without having to own an internet-enabled device. EDKASA envisions deploying a network of low-cost franchises that will create flipped classrooms to distribute EDKASA’s live teaching web-streams at physical locations. -

Secondary Education Degree

Secondary Education Degree Bachelor of Science in Education (B.S.Ed.) Guide teens by teaching them and helping them find their interests, now and for their future. High school is a critical time of education – and teaching students during their teen years has its challenges and rewards. When you earn your Secondary Education degree from UND, you’ll learn how to effectively teach life skills and knowledge for students in 7th through 12th grade. Program type: Major Format: On Campus Est. time to complete: 4 years Credit hours: 125 What is a secondary education degree? Application Deadlines Fall: Aug. 16 Spring: Dec. 15 Summer: May 1 The University of North Dakota offers the most comprehensive selection of Teacher Education majors, minors and endorsements in the state. The Bachelor of Science in Education in Secondary Education prepares you to teach in high school classrooms in North Dakota, Minnesota and across the nation. Through the College of Education & Human Development, in partnership with the College of Arts & Sciences, you can: Prepare to be a high school teacher in 11 areas to meet students’ current and future educational needs Learn innovative teaching practices to help students succeed in rural or urban settings Become subject experts in content areas such as English, Sciences, Social Studies, Mathematics, Music, Foreign Languages and Art You’ll complete a double major earning a B.S.Ed. in Secondary Education for high school teacher preparation. You’ll also complete a B.A. or B.S. related to your content area of choice (e.g., English, Mathematics, Chemistry, etc.). Our courses are designed to provide you with real-world classroom experiences. -

English Language Learning (ELL) Support

Welcome to British Columbia Education is vital to a healthy and successful life in Canada. In British Columbia, all children between the ages of 5 and 16 must go to school. Most children go to public school; some children go to independent (private) schools. Children usually attend the public school closest to their home. After secondary school, students can go on to postsecondary study at colleges, technical schools, and universities. British Columbia’s Education System In British Columbia (BC), the school system is made up of public schools and independent (private schools). Public schools are fully funded by the provincial government. Independent schools are only partially funded by government. Both the provincial government and local boards of education manage the public school system (Kindergarten to Grade 12). The provincial government funds the school system and sets the legislation, regulations, and policies to ensure every school meets provincial standards and every student receives a high-quality education. For more information about BC’s Ministry of Education, visit the website at: www.gov.bc.ca/bced For more information about your child’s education in BC, contact your local Welcome Centre or school. Registration Your Refugee Assistance Provider (RAP) or local sponsor will be able to help you register your child(ren) for school. The school will be able to provide information about learning assistance, and English Language Learning (ELL) support. Some public schools also have settlement workers, from the Settlement Workers in Schools (SWIS) Program, who will help you and your children settle into your new school and community. Elementary, Middle and Secondary Schools Children usually start elementary school in the same year that they turn five years old. -

A Plan to Expand Preschool in the Elementary and Secondary Education Act February 19, 2015

A Plan to Expand Preschool in the Elementary and Secondary Education Act February 19, 2015 Today, more than half of children from low-income families start school behind without the foundational skills that set them up to learn and be successful in kindergarten and beyond. Knowing this, states and cities as diverse as Oklahoma, Georgia, New York City, Boston, San Antonio, and Washington, D.C., have taken steps to expand access to preschool. Research from these early-adopter states and districts shows that low-income children can gain an average of four months of additional learning. In the highest quality programs, they gain 6 to 12 months, significantly narrowing the school readiness gap.1 For this reason, preschool is a popular policy across diverse and bipartisan stakeholders. Leaders in the business, military, and law enforcement have spoken in favor of further public investments in preschool. And Republican and Democratic governors have been outspoken proponents of expanding access to preschool. While Congress considers changes to the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, or ESEA, it has an opportunity to make a big difference in the lives of low-income children by making high-quality preschool a reality for those who don’t currently have access. The goal of ESEA is to ensure that all students, particularly disadvantaged students, have access to good education. Incorporating early learning in ESEA is critical to achieving this goal, as many of the poorest children do not have access to high-quality early child- hood programs. Sen. Patty Murray (D-WA) identified early childhood education as a key priority for ESEA reauthorization, and House Democrats led by Rep. -

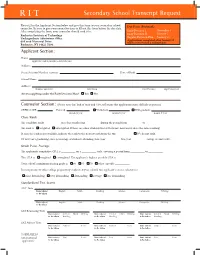

Secondary School Transcript Request

Secondary School Transcript Request SecondarySecondarySecondary School School School Transcript Transcript Transcript Request Request Request Secondary School Transcript Request Please fill in the Applicant Section below and give this form to your secondary school Please fill in the Applicant Section below and give this form to your secondary school Please fill in the Applicant Section below and give this form to your secondary school counselor.PleasePlease fill Be in fillsure the in to theApplicant give Applicant your Section counselor Section below timebelow and to giveandfill thisgiveout thisformthis formform to your tobefore yoursecondary the secondary due schooldate. school Due Dates (Postmark) counselor. Be sure to give your counselor time to fill out this form before the due date. Due Dates (Postmark) Due Dates (Postmark) Due DueDates Dates (Postmark) (Postmark) counselor. Be sure to give your counselor time to fill out this form before the due date. Aftercounselor. completingcounselor. Be sure Bethe sureto form, give to giveyour your counselor counselor shouldtime timeto sendfill to outitfill to: thisout formthis form before before the duethe date.due date.Early Decision Plan November 15 After completing the form, your counselor should send it to: Early Decision Plan November 15 After completing the form, your counselor should send it to: Early Decision Plan November 15 AfterAfter completing completing the form, the form, your yourcounselor counselor should should send sendit to: it to: RegularEarlyEarly DecisionDecision Decision