Engineering Microeconomics Fall 2017 (3 Credits)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global Marketing Services Henning Schoenenberger 09.2011 Code

Code Description English A Science A11007 Science, general A12000 History of Science B Biomedicine B0000X Biomedicine general B11001 Cancer Research B12008 Human Genetics B12010 Gene Expression B12020 Gene Therapy B12030 Gene Function B12040 Cytogenetics B12050 Microarrays B13004 Human Physiology B14000 Immunology B14010 Antibodies B15007 Laboratory Medicine B16003 Medical Microbiology B16010 Vaccine B16020 Drug Resistance B1700X Molecular Medicine B18006 Neurosciences B18010 Neurochemistry B19002 Parasitology B21007 Pharmacology/Toxicology B21010 Pharmaceutical Sciences/Technology B22003 Virology B23000 Forensic Science C Chemistry C00004 Chemistry/Food Science, general C11006 Analytical Chemistry C11010 Mass Spectrometry C11020 Spectroscopy/Spectrometry C11030 Chromatography C12002 Biotechnology C12010 Applied Microbiology C12029 Biochemical Engineering C12037 Genetic Engineering C12040 Microengineering C12050 Electroporation C13009 Computer Applications in Chemistry C14005 Documentation and Information in Chemistry C15001 Food Science C16008 Inorganic Chemistry C17004 Math. Applications in Chemistry C18000 Nutrition C19007 Organic Chemistry C19010 Bioorganic Chemistry C19020 Organometallic Chemistry C19030 Carbohydrate Chemistry C21001 Physical Chemistry C21010 Electrochemistry C22008 Polymer Sciences C23004 Safety in Chemistry, Dangerous Goods C24000 Textile Engineering C25007 Theoretical and Computational Chemistry C26003 Gmelin C27000 Industrial Chemistry/Chemical Engineering C28000 Medicinal Chemistry C29000 Catalysis C31000 Nuclear -

Principles of MICROECONOMICS an Open Text by Douglas Curtis and Ian Irvine

with Open Texts Principles of MICROECONOMICS an Open Text by Douglas Curtis and Ian Irvine VERSION 2017 – REVISION B ADAPTABLE | ACCESSIBLE | AFFORDABLE Creative Commons License (CC BY-NC-SA) advancing learning Champions of Access to Knowledge OPEN TEXT ONLINE ASSESSMENT All digital forms of access to our high- We have been developing superior on- quality open texts are entirely FREE! All line formative assessment for more than content is reviewed for excellence and is 15 years. Our questions are continuously wholly adaptable; custom editions are pro- adapted with the content and reviewed for duced by Lyryx for those adopting Lyryx as- quality and sound pedagogy. To enhance sessment. Access to the original source files learning, students receive immediate per- is also open to anyone! sonalized feedback. Student grade reports and performance statistics are also provided. SUPPORT INSTRUCTOR SUPPLEMENTS Access to our in-house support team is avail- Additional instructor resources are also able 7 days/week to provide prompt resolu- freely accessible. Product dependent, these tion to both student and instructor inquiries. supplements include: full sets of adaptable In addition, we work one-on-one with in- slides and lecture notes, solutions manuals, structors to provide a comprehensive sys- and multiple choice question banks with an tem, customized for their course. This can exam building tool. include adapting the text, managing multi- ple sections, and more! Contact Lyryx Today! [email protected] advancing learning Principles of Microeconomics an Open Text by Douglas Curtis and Ian Irvine Version 2017 — Revision B BE A CHAMPION OF OER! Contribute suggestions for improvements, new content, or errata: A new topic A new example An interesting new question Any other suggestions to improve the material Contact Lyryx at [email protected] with your ideas. -

Advances in Energy Forecasting Models Based on Engineering

20 Sep 2004 14:55 AR AR227-EG29-10.tex AR227-EG29-10.SGM LaTeX2e(2002/01/18) P1: GCE 10.1146/annurev.energy.29.062403.102042 Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2004. 29:345–81 doi: 10.1146/annurev.energy.29.062403.102042 First published online as a Review in Advance on July 30, 2004 ADVANCES IN ENERGY FORECASTING MODELS ∗ BASED ON ENGINEERING ECONOMICS Ernst Worrell,1 Stephan Ramesohl,2 and Gale Boyd3 1Energy Analysis Department, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, California 94720; email: [email protected] 2Energy Division, Wuppertal Institute for Climate, Environment, Energy, 42103 Wuppertal, Germany; email: [email protected] 3Decision and Information Sciences Division, Argonne National Laboratory, Argonne, Illinois 60439; email: [email protected] KeyWords energy modeling, industry, policy, technology ■ Abstract New energy efficiency policies have been introduced around the world. Historically, most energy models were reasonably equipped to assess the impact of classical policies, such as a subsidy or change in taxation. However, these tools are often insufficient to assess the impact of alternative policy instruments. We evalu- ate the so-called engineering economic models used to assess future industrial en- ergy use. Engineering economic models include the level of detail commonly needed to model the new types of policies considered. We explore approaches to improve the realism and policy relevance of engineering economic modeling frameworks. We also explore solutions to strengthen the policy usefulness of engineering eco- nomic analysis that can be built from a framework of multidisciplinary coopera- tion. The review discusses the main modeling approaches currently used and eval- uates the weaknesses in current models. -

Microeconomics III Oligopoly — Preface to Game Theory

Microeconomics III Oligopoly — prefacetogametheory (Mar 11, 2012) School of Economics The Interdisciplinary Center (IDC), Herzliya Oligopoly is a market in which only a few firms compete with one another, • and entry of new firmsisimpeded. The situation is known as the Cournot model after Antoine Augustin • Cournot, a French economist, philosopher and mathematician (1801-1877). In the basic example, a single good is produced by two firms (the industry • is a “duopoly”). Cournot’s oligopoly model (1838) — A single good is produced by two firms (the industry is a “duopoly”). — The cost for firm =1 2 for producing units of the good is given by (“unit cost” is constant equal to 0). — If the firms’ total output is = 1 + 2 then the market price is = − if and zero otherwise (linear inverse demand function). We ≥ also assume that . The inverse demand function P A P=A-Q A Q To find the Nash equilibria of the Cournot’s game, we can use the proce- dures based on the firms’ best response functions. But first we need the firms payoffs(profits): 1 = 1 11 − =( )1 11 − − =( 1 2)1 11 − − − =( 1 2 1)1 − − − and similarly, 2 =( 1 2 2)2 − − − Firm 1’s profit as a function of its output (given firm 2’s output) Profit 1 q'2 q2 q2 A c q A c q' Output 1 1 2 1 2 2 2 To find firm 1’s best response to any given output 2 of firm 2, we need to study firm 1’s profit as a function of its output 1 for given values of 2. -

ECON - Economics ECON - Economics

ECON - Economics ECON - Economics Global Citizenship Program ECON 3020 Intermediate Microeconomics (3) Knowledge Areas (....) This course covers advanced theory and applications in microeconomics. Topics include utility theory, consumer and ARTS Arts Appreciation firm choice, optimization, goods and services markets, resource GLBL Global Understanding markets, strategic behavior, and market equilibrium. Prerequisite: ECON 2000 and ECON 3000. PNW Physical & Natural World ECON 3030 Intermediate Macroeconomics (3) QL Quantitative Literacy This course covers advanced theory and applications in ROC Roots of Cultures macroeconomics. Topics include growth, determination of income, employment and output, aggregate demand and supply, the SSHB Social Systems & Human business cycle, monetary and fiscal policies, and international Behavior macroeconomic modeling. Prerequisite: ECON 2000 and ECON 3000. Global Citizenship Program ECON 3100 Issues in Economics (3) Skill Areas (....) Analyzes current economic issues in terms of historical CRI Critical Thinking background, present status, and possible solutions. May be repeated for credit if content differs. Prerequisite: ECON 2000. ETH Ethical Reasoning INTC Intercultural Competence ECON 3150 Digital Economy (3) Course Descriptions The digital economy has generated the creation of a large range OCOM Oral Communication of significant dedicated businesses. But, it has also forced WCOM Written Communication traditional businesses to revise their own approach and their own value chains. The pervasiveness can be observable in ** Course fulfills two skill areas commerce, marketing, distribution and sales, but also in supply logistics, energy management, finance and human resources. This class introduces the main actors, the ecosystem in which they operate, the new rules of this game, the impacts on existing ECON 2000 Survey of Economics (3) structures and the required expertise in those areas. -

Engineering Economy for Economists

AC 2008-2866: ENGINEERING ECONOMY FOR ECONOMISTS Peter Boerger, Engineering Economic Associates, LLC Peter Boerger is an independent consultant specializing in solving problems that incorporate both technological and economic aspects. He has worked and published for over 20 years on the interface between engineering, economics and public policy. His education began with an undergraduate degree in Mechanical Engineering from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, adding a Master of Science degree in a program of Technology and Public Policy from Purdue University and a Ph.D. in Engineering Economics from the School of Industrial Engineering at Purdue University. His firm, Engineering Economic Associates, is located in Indianapolis, IN. Page 13.503.1 Page © American Society for Engineering Education, 2008 Engineering Economy for Economists 1. Abstract The purpose of engineering economics is generally accepted to be helping engineers (and others) to make decisions regarding capital investment decisions. A less recognized but potentially fruitful purpose is to help economists better understand the workings of the economy by providing an engineering (as opposed to econometric) view of the underlying workings of the economy. This paper provides a review of some literature related to this topic and some thoughts on moving forward in this area. 2. Introduction Engineering economy is inherently an interdisciplinary field, sitting, as the name implies, between engineering and some aspect of economics. One has only to look at the range of academic departments represented by contributors to The Engineering Economist to see the many fields with which engineering economy already relates. As with other interdisciplinary fields, engineering economy has the promise of huge advancements and the risk of not having a well-defined “home base”—the risk of losing resources during hard times in competition with other academic departments/specialties within the same department. -

FALL 2021 COURSE SCHEDULE August 23 –– December 9, 2021

9/15/21 DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS FALL 2021 COURSE SCHEDULE August 23 –– December 9, 2021 Course # Class # Units Course Title Day Time Location Instruction Mode Instructor Limit 1078-001 20457 3 Mathematical Tools for Economists 1 MWF 8:00-8:50 ECON 117 IN PERSON Bentz 47 1078-002 20200 3 Mathematical Tools for Economists 1 MWF 6:30-7:20 ECON 119 IN PERSON Hurt 47 1078-004 13409 3 Mathematical Tools for Economists 1 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Marein 71 1088-001 18745 3 Mathematical Tools for Economists 2 MWF 6:30-7:20 HLMS 141 IN PERSON Zhou, S 47 1088-002 20748 3 Mathematical Tools for Economists 2 MWF 8:00-8:50 HLMS 211 IN PERSON Flynn 47 2010-100 19679 4 Principles of Microeconomics 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Keller 500 2010-200 14353 4 Principles of Microeconomics 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Carballo 500 2010-300 14354 4 Principles of Microeconomics 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Bottan 500 2010-600 14355 4 Principles of Microeconomics 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Klein 200 2010-700 19138 4 Principles of Microeconomics 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Gruber 200 2020-100 14356 4 Principles of Macroeconomics 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Valkovci 400 3070-010 13420 4 Intermediate Microeconomic Theory MWF 9:10-10:00 ECON 119 IN PERSON Barham 47 3070-020 21070 4 Intermediate Microeconomic Theory TTH 2:20-3:35 ECON 117 IN PERSON Chen 47 3070-030 20758 4 Intermediate Microeconomic Theory TTH 11:10-12:25 ECON 119 IN PERSON Choi 47 3070-040 21443 4 Intermediate Microeconomic Theory MWF 1:50-2:40 ECON 119 IN PERSON Bottan 47 3080-001 22180 3 Intermediate Macroeconomic Theory MWF 11:30-12:20 -

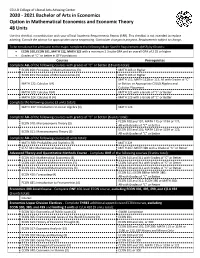

2020-2021 Bachelor of Arts in Economics Option in Mathematical

CSULB College of Liberal Arts Advising Center 2020 - 2021 Bachelor of Arts in Economics Option in Mathematical Economics and Economic Theory 48 Units Use this checklist in combination with your official Academic Requirements Report (ARR). This checklist is not intended to replace advising. Consult the advisor for appropriate course sequencing. Curriculum changes in progress. Requirements subject to change. To be considered for admission to the major, complete the following Major Specific Requirements (MSR) by 60 units: • ECON 100, ECON 101, MATH 122, MATH 123 with a minimum 2.3 suite GPA and an overall GPA of 2.25 or higher • Grades of “C” or better in GE Foundations Courses Prerequisites Complete ALL of the following courses with grades of “C” or better (18 units total): ECON 100: Principles of Macroeconomics (3) MATH 103 or Higher ECON 101: Principles of Microeconomics (3) MATH 103 or Higher MATH 111; MATH 112B or 113; All with Grades of “C” MATH 122: Calculus I (4) or Better; or Appropriate CSULB Algebra and Calculus Placement MATH 123: Calculus II (4) MATH 122 with a Grade of “C” or Better MATH 224: Calculus III (4) MATH 123 with a Grade of “C” or Better Complete the following course (3 units total): MATH 247: Introduction to Linear Algebra (3) MATH 123 Complete ALL of the following courses with grades of “C” or better (6 units total): ECON 100 and 101; MATH 115 or 119A or 122; ECON 310: Microeconomic Theory (3) All with Grades of “C” or Better ECON 100 and 101; MATH 115 or 119A or 122; ECON 311: Macroeconomic Theory (3) All with -

Nine Lives of Neoliberalism

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Plehwe, Dieter (Ed.); Slobodian, Quinn (Ed.); Mirowski, Philip (Ed.) Book — Published Version Nine Lives of Neoliberalism Provided in Cooperation with: WZB Berlin Social Science Center Suggested Citation: Plehwe, Dieter (Ed.); Slobodian, Quinn (Ed.); Mirowski, Philip (Ed.) (2020) : Nine Lives of Neoliberalism, ISBN 978-1-78873-255-0, Verso, London, New York, NY, https://www.versobooks.com/books/3075-nine-lives-of-neoliberalism This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/215796 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative -

Principles of Microeconomics

PRINCIPLES OF MICROECONOMICS A. Competition The basic motivation to produce in a market economy is the expectation of income, which will generate profits. • The returns to the efforts of a business - the difference between its total revenues and its total costs - are profits. Thus, questions of revenues and costs are key in an analysis of the profit motive. • Other motivations include nonprofit incentives such as social status, the need to feel important, the desire for recognition, and the retaining of one's job. Economists' calculations of profits are different from those used by businesses in their accounting systems. Economic profit = total revenue - total economic cost • Total economic cost includes the value of all inputs used in production. • Normal profit is an economic cost since it occurs when economic profit is zero. It represents the opportunity cost of labor and capital contributed to the production process by the producer. • Accounting profits are computed only on the basis of explicit costs, including labor and capital. Since they do not take "normal profits" into consideration, they overstate true profits. Economic profits reward entrepreneurship. They are a payment to discovering new and better methods of production, taking above-average risks, and producing something that society desires. The ability of each firm to generate profits is limited by the structure of the industry in which the firm is engaged. The firms in a competitive market are price takers. • None has any market power - the ability to control the market price of the product it sells. • A firm's individual supply curve is a very small - and inconsequential - part of market supply. -

Engineering Economics for Public Water Utilities

Engineering Economics for Public Water Utilities Max Maurer Eawag: Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology Imprint Author Prof. Dr. Max Maurer, Institute of Environmental Engineering, ETH-Zürich, Switzerland [email protected] Aim This script constitutes part of my lecture ‘Infrastructure Systems in Urban Water Management’ given at ETH Zürich, Switzerland Version 4.7, Jan 2019 License Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) Title photo Wastewater Treatment Plant (Mönchaltorf, ZH) Maurer: Engineering Economics Contents 1. Aim of this script ......................................................................................................................... - 5 - Inflation, Interest & Discount Rate ...................................................................................................... - 7 - 2. The strange concept of money .................................................................................................. - 8 - 3. Inflation........................................................................................................................................ - 8 - 4. Interest rates ............................................................................................................................. - 10 - 5. Discount rate ............................................................................................................................. - 10 - 6. Replacement value .................................................................................................................. -

Economics and Engineering” Pedro Garcia Duarte and Yann Giraud

Introduction: From “Economics as Engineering” to “Economics and Engineering” Pedro Garcia Duarte and Yann Giraud The Transformation of Economics into an Engineering Science: From Analogies to Interactions In recent years, economists, who in the past had mostly insisted on their discipline’s strength as a rigorous social science, have turned to its larger role in transforming society. As early as 2002, Alvin Roth, the Stan- ford-educated economist who received the Nobel memorial prize in 2012, has claimed that members of his community should think of themselves as engineers rather than scientists. By this he meant that they should not be interested solely in the making of theoretical models but also in con- fronting these models with the complexities of real-life situations, which is what engineering is allegedly about. He pointed to the rise of the new sub eld of market design, which he had helped develop, as characteristic of an engineer’s stance and provided several examples of engineering practices applied to economics: the design of labor clearinghouses—such as the entry-level labor market for American physicians—and that of the Federal Communications Commission spectrum auctions (Roth 2002). We want to thank the Center for the History of Political Economy and Duke University Press for their support, as well as the many referees who helped us during the editorial process. Yann Giraud wishes to point out that his research has been supported by the project Labex MME-DII (ANR11–LBX-0023–01). Pedro Duarte acknowledges the nancial support of the Institute for Advanced Studies, at the Université de Cergy-Pontoise, for visiting professorships (2016, 2018) that were critical for the shaping of this joint project.