The Influence of Historic Violin Treatises on Modern Teaching and Performance Practices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

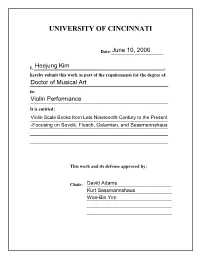

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ ViolinScaleBooks fromLateNineteenth-Centurytothe Present -FocusingonSevcik,Flesch,Galamian,andSassmannshaus Adocumentsubmittedtothe DivisionofGraduateStudiesandResearchofthe UniversityofCincinnati Inpartialfulfillmentoftherequirementsforthedegreeof DOCTORAL OFMUSICALARTS inViolinPerformance 2006 by HeejungKim B.M.,Seoul NationalUniversity,1995 M.M.,TheUniversityof Cincinnati,1999 Advisor:DavidAdams Readers:KurtSassmannshaus Won-BinYim ABSTRACT Violinists usuallystart practicesessionswithscale books,andtheyknowthe importanceofthem asatechnical grounding.However,performersandstudents generallyhavelittleinformation onhowscale bookshave beendevelopedandwhat detailsaredifferentamongmanyscale books.Anunderstanding ofsuchdifferences, gainedthroughtheidentificationandcomparisonofscale books,canhelp eachviolinist andteacherapproacheachscale bookmoreintelligently.Thisdocumentoffershistorical andpracticalinformationforsome ofthemorewidelyused basicscalestudiesinviolin playing. Pedagogicalmaterialsforviolin,respondingtothetechnicaldemands andmusical trendsoftheinstrument , haveincreasedinnumber.Amongthem,Iwillexamineand comparethe contributionstothescale -

A Comparative Analysis of the Six Duets for Violin and Viola by Michael Haydn and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE SIX DUETS FOR VIOLIN AND VIOLA BY MICHAEL HAYDN AND WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART by Euna Na Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University May 2021 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee ______________________________________ Frank Samarotto, Research Director ______________________________________ Mark Kaplan, Chair ______________________________________ Emilio Colón ______________________________________ Kevork Mardirossian April 30, 2021 ii I dedicate this dissertation to the memory of my mentor Professor Ik-Hwan Bae, a devoted musician and educator. iii Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................ iv List of Examples .............................................................................................................................. v List of Tables .................................................................................................................................. vii Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: The Unaccompanied Instrumental Duet... ................................................................... 3 A General Overview -

The Science of String Instruments

The Science of String Instruments Thomas D. Rossing Editor The Science of String Instruments Editor Thomas D. Rossing Stanford University Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA) Stanford, CA 94302-8180, USA [email protected] ISBN 978-1-4419-7109-8 e-ISBN 978-1-4419-7110-4 DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-7110-4 Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2010 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer ScienceþBusiness Media (www.springer.com) Contents 1 Introduction............................................................... 1 Thomas D. Rossing 2 Plucked Strings ........................................................... 11 Thomas D. Rossing 3 Guitars and Lutes ........................................................ 19 Thomas D. Rossing and Graham Caldersmith 4 Portuguese Guitar ........................................................ 47 Octavio Inacio 5 Banjo ...................................................................... 59 James Rae 6 Mandolin Family Instruments........................................... 77 David J. Cohen and Thomas D. Rossing 7 Psalteries and Zithers .................................................... 99 Andres Peekna and Thomas D. -

Black Violin

This section is part of a full NEW VICTORY® SCHOOL TOOLTM Resource Guide. For the complete guide, including information about the NEW VICTORY Education Department check out: newvictorYschooltools.org ® inside | black violin BEFORE EN ROUTE AFTER BEYOND INSIDE INSIDE THE SHOW/COMPANY • closer look • where in the world INSIDE THE ART FORM • WHAT DO YOUR STUDENTS KNOW NOW? CREATIVITY PAGE: Charting the Charts WHAT IS “INSIDE” BLACK VIOLIN? INSIDE provides teachers and students a behind-the-curtain look at the artists, the company and the art form of this production. Utilize this resource to learn more about the artists on the NEW VICTORY stage, how far they’ve traveled and their inspiration for creating this show. In addition to information that will enrich your students’ experience at the theater, you will find a Creativity Page as a handout to build student anticipation around their trip to The New Victory. Photos: Colin Brennen MAKING CONNECTIONS TO LEARNING STANDARDS NEW VICTORY SCHOOL TOOL Resource Guides align with the Common Core State Standards, New York State Learning Standards and New York City Blueprint for Teaching and Learning in the Arts. We believe that these standards support both the high quality instruction and deep engagement that The New Victory Theater strives to achieve in its arts education practice. COMMON CORE NEW YORK STATE STANDARDS BLUEPRINT FOR THE ARTS Speaking and Listening Standards: 1 Arts Standards: Standard 4 Music Standards: Developing Music English Language Arts Standards: Literacy; Making Connections -

To the New Owner by Emmett Chapman

To the New Owner by Emmett Chapman contents PLAYING ACTION ADJUSTABLE COMPONENTS FEATURES DESIGN TUNINGS & CONCEPT STRING MAINTENANCE BATTERIES GUARANTEE This new eight-stringed “bass guitar” was co-designed by Ned Steinberger and myself to provide a dual role instrument for those musicians who desire to play all methods on one fretboard - picking, plucking, strumming, and the two-handed tapping Stick method. PLAYING ACTION — As with all Stick models, this instrument is fully adjustable without removal of any components or detuning of strings. String-to-fret action can be set higher at the bridge and nut to provide a heavier touch, allowing bass and guitar players to “dig in” more. Or the action can be set very low for tapping, as on The Stick. The precision fretwork is there (a straight board with an even plane of crowned and leveled fret tips) and will accommodate the same Stick low action and light touch. Best kept secret: With the action set low for two-handed tapping as it comes from my setup table, you get a combined advantage. Not only does the low setup optimize tapping to its SIDE-SADDLE BRIDGE SCREWS maximum ease, it also allows all conventional bass guitar and guitar techniques, as long as your right hand lightens up a bit in its picking/plucking role. In the process, all volumes become equal, regardless of techniques used, and you gain total control of dynamics and expression. This allows seamless transition from tapping to traditional playing methods on this dual role instrument. Some players will want to compromise on low action of the lower bass strings and set the individual bridge heights a bit higher, thereby duplicating the feel of their bass or guitar. -

1 Francesco Geminiani

Francesco Geminiani: Opera Omnia Volume 5. 6 Sonatas Op. 5 (versions for cello and basso continuo H. 103-108; for violin and basso continuo H. 109-114). Christopher Hogwood, editor. Ut Orpheus Edizioni, 2010 (112 pp. clothbound). “Although Geminiani (1687‐1762) was held to be the equal of Corelli in his own day—and indeed thought by some to be superior to his contemporary Handel in instrumental composition—his considerable output of music and didactic writings has only been available in piecemeal fashion, much of it never reissued since his lifetime except in facsimile, and thus largely inaccessible to modern performers. This lack of material designed for practical performance has concealed the enormous originality he showed both in writing and re‐writing his own music, and that of Corelli. Francesco Geminiani Opera Omnia rectifies this omission with the first uniform and accurate scholarly edition of all versions of his music and writings in a form that allows pertinent comparison and reevaluation.” So opens the general preface to this first volume (of seventeen) in Ut Orpheus’ complete Geminiani Edition, and a more felicitous introduction it would be difficult to imagine. For a composer of such importance, particularly one whose limited output stands well within the logistical and economic constraints of the music publishing industry, his neglect has been astonishing. Until the period instrument movement got going in the past several decades, this was also true of Geminiani’s representation on recordings‐‐a fact that resulted in a particularly amusing episode from my own personal wanderings through the sometimes strange world of classical music collecting and appreciation. -

What Is the “Ševčík Method”?

Course: CA1004 Degree Project, Master, Classical, 30hp 2020 Master's Programme in Classical Music at Edsberg Manor | 120.0 hp Department of Classical Music Supervisor: Sven Åberg Angelika Kwiatkowska What is the “Ševčík Method”? Deeper understanding of Otakar Ševčík’s excercises for violin based on the example of his 40 Variations, op. 3 Written reflection within independent project The sounding part of the project is the following recordings: Mozart – Symphony no. 39 Finale – before Mozart – Symphony no. 39 Finale – after Rossini – Overture La Gazza Ladra - before Rossini – Overture La Gazza Ladra - after Abstract In this thesis I have studied the so-called “Ševčík method” based on the example of his 40 Variations, op. 3. I’ve tried to achieve a deeper understanding of what the exercises are good for and how they work. I took a closer look at Otakar Ševčík’s life and work history, I also investigated other’s opinions and judgements of the “method” that were appearing in press and literature during the last hundred years. The practical part of my project is the experiment that I’ve put myself through. I was diligently practicing 40 Variations every day, trying to improve my technique and learn by playing how to apply those exercises in real life. As a result of this process I’ve developed my bow technique and gained better understanding of how to use Ševčík’s exercises. Keywords: Violin, technique, exercises, bow technique, right-hand technique, Ševčík I Contents Introduction ...................................................................................................... -

STRAVINSKY's NEO-CLASSICISM and HIS WRITING for the VIOLIN in SUITE ITALIENNE and DUO CONCERTANT by ©2016 Olivia Needham Subm

STRAVINSKY’S NEO-CLASSICISM AND HIS WRITING FOR THE VIOLIN IN SUITE ITALIENNE AND DUO CONCERTANT By ©2016 Olivia Needham Submitted to the graduate degree program in School of Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. ________________________________________ Chairperson: Paul Laird ________________________________________ Véronique Mathieu ________________________________________ Bryan Haaheim ________________________________________ Philip Kramp ________________________________________ Jerel Hilding Date Defended: 04/15/2016 The Dissertation Committee for Olivia Needham certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: STRAVINSKY’S NEO-CLASSICISM AND HIS WRITING FOR THE VIOLIN IN SUITE ITALIENNE AND DUO CONCERTANT ________________________________________ Chairperson: Paul Laird Date Approved: 04/15/2016 ii ABSTRACT This document is about Stravinsky and his violin writing during his neoclassical period, 1920-1951. Stravinsky is one of the most important neo-classical composers of the twentieth century. The purpose of this document is to examine how Stravinsky upholds his neoclassical aesthetic in his violin writing through his two pieces, Suite italienne and Duo Concertant. In these works, Stravinsky’s use of neoclassicism is revealed in two opposite ways. In Suite Italienne, Stravinsky based the composition upon actual music from the eighteenth century. In Duo Concertant, Stravinsky followed the stylistic features of the eighteenth century without parodying actual music from that era. Important types of violin writing are described in these two works by Stravinsky, which are then compared with examples of eighteenth-century violin writing. iii Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) was born in Oranienbaum (now Lomonosov) in Russia near St. -

The Sonatas Opus 4 1739

Rudolf Rasch: The Thirty-One Works of Francesco Geminiani Work Eight: The Violin Sonatas Opus 4 (1739) Rudolf Rasch The Thirty-One Works of Francesco Geminiani Work Eight: The Violin Sonatas Opus 4 (1739) Please refer to this document in the following way: Rudolf Rasch, The Thirty-One Works of Francesco Geminiani: Work Eight: The Violin Sonatas Opus 4 (1739) https://geminiani.sites.uu.nl For remarks, suggestions, additions and corrections: [email protected] © Rudolf Rasch, Utrecht/Houten, 2019 24 December 2020 1 Rudolf Rasch: The Thirty-One Works of Francesco Geminiani Work Eight: The Violin Sonatas Opus 4 (1739) WORK EIGHT THE VIOLIN SONATAS OP. 4 (1739) CONTENTS The Violin Sonatas Op. 4 (1739) ....................................................................................................................... 3 The Sonatas ..................................................................................................................................................... 11 Notation ........................................................................................................................................................... 18 Engraving and Printing .................................................................................................................................... 24 The British Edition (1739) ............................................................................................................................... 30 The French Issue (1740) ................................................................................................................................. -

Leopold and Wolfgang Mozart's View of the World

Between Aufklärung and Sturm und Drang: Leopold and Wolfgang Mozart’s View of the World by Thomas McPharlin Ford B. Arts (Hons.) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy European Studies – School of Humanities and Social Sciences University of Adelaide July 2010 i Between Aufklärung and Sturm und Drang: Leopold and Wolfgang Mozart’s View of the World. Preface vii Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Leopold Mozart, 1719–1756: The Making of an Enlightened Father 10 1.1: Leopold’s education. 11 1.2: Leopold’s model of education. 17 1.3: Leopold, Gellert, Gottsched and Günther. 24 1.4: Leopold and his Versuch. 32 Chapter 2: The Mozarts’ Taste: Leopold’s and Wolfgang’s aesthetic perception of their world. 39 2.1: Leopold’s and Wolfgang’s general aesthetic outlook. 40 2.2: Leopold and the aesthetics in his Versuch. 49 2.3: Leopold’s and Wolfgang’s musical aesthetics. 53 2.4: Leopold’s and Wolfgang’s opera aesthetics. 56 Chapter 3: Leopold and Wolfgang, 1756–1778: The education of a Wunderkind. 64 3.1: The Grand Tour. 65 3.2: Tour of Vienna. 82 3.3: Tour of Italy. 89 3.4: Leopold and Wolfgang on Wieland. 96 Chapter 4: Leopold and Wolfgang, 1778–1781: Sturm und Drang and the demise of the Mozarts’ relationship. 106 4.1: Wolfgang’s Paris journey without Leopold. 110 4.2: Maria Anna Mozart’s death. 122 4.3: Wolfgang’s relations with the Weber family. 129 4.4: Wolfgang’s break with Salzburg patronage. -

Guitar Anatomy Glossary

GUITAR ANATOMY GLOSSARY abalone: an iridescent lining found in the inner shell of the abalone mollusk that is often used alongside mother of pearl; commonly used as an inlay material. action: the distance between the strings and the fretboard; the open space between strings and frets. back: the part of the guitar body held against the player’s chest; it is reflective and resonant, and usually made of a hardwood. backstrip: a decorative inlay that runs the length of the center back of a stringed instrument. binding: the inlaid corner trim at the very edges of an instrument’s body or neck, used to provide aesthetic appeal, seal open wood and to protect the edge of the face and back, as well as the glue joint. bout: the upper or lower outside curve of a guitar or other instrument body. body: an acoustic guitar body; the sound-producing chamber to which the neck and bridge are attached. body depth: the measurement of the guitar body at the headblock and tailblock after the top and back have been assembled to the rim. bracing: the bracing on the inside of the instrument that supports the top and back to prevent warping and breaking, and creates and controls the voice of the guitar. The back of the instrument is braced to help distribute the force exerted by the neck on the body, to reflect sound from the top and act sympathetically to the vibrations of the top. bracing, profile: the contour of the brace, which is designed to control strength and tone. bracing, scalloped: used to describe the crests and troughs of the braces where mass has been removed to accentuate certain nodes. -

Secrets of Stradivarius' Unique Violin Sound Revealed, Prof Says 22 January 2009

Secrets Of Stradivarius' unique violin sound revealed, prof says 22 January 2009 Nagyvary obtained minute wood samples from restorers working on Stradivarius and Guarneri instruments ("no easy trick and it took a lot of begging to get them," he adds). The results of the preliminary analysis of these samples, published in "Nature" in 2006, suggested that the wood was brutally treated by some unidentified chemicals. For the present study, the researchers burned the wood slivers to ash, the only way to obtain accurate readings for the chemical elements. They found numerous chemicals in the wood, among them borax, fluorides, chromium and iron salts. Violin "Borax has a long history as a preservative, going back to the ancient Egyptians, who used it in mummification and later as an insecticide," For centuries, violin makers have tried and failed to Nagyvary adds. reproduce the pristine sound of Stradivarius and Guarneri violins, but after 33 years of work put into "The presence of these chemicals all points to the project, a Texas A&M University professor is collaboration between the violin makers and the confident the veil of mystery has now been lifted. local drugstore and druggist at the time. Their probable intent was to treat the wood for Joseph Nagyvary, a professor emeritus of preservation purposes. Both Stradivari and biochemistry, first theorized in 1976 that chemicals Guarneri would have wanted to treat their violins to used on the instruments - not merely the wood and prevent worms from eating away the wood because the construction - are responsible for the distinctive worm infestations were very widespread at that sound of these violins.