Housing Enslaved Cubans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Cite Complete Issue More Information About This Article Journal's Webpage in Redalyc.Org Scientific Information System Re

Cultivos Tropicales ISSN: 1819-4087 Ediciones INCA Benítez-Fernández, Bárbara; Crespo-Morales, Anaisa; Casanova, Caridad; Méndez-Bordón, Aliek; Hernández-Beltrán, Yaima; Ortiz- Pérez, Rodobaldo; Acosta-Roca, Rosa; Romero-Sarduy, María Isabel Impactos de la estrategia de género en el sector agropecuario, a través del Proyecto de Innovación Agropecuaria Local (PIAL) Cultivos Tropicales, vol. 42, no. 1, e04, 2021, January-March Ediciones INCA DOI: https://doi.org/10.1234/ct.v42i1.1578 Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=193266707004 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System Redalyc More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Journal's webpage in redalyc.org Portugal Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative Cultivos Tropicales, 2021, vol. 42, no. 1, e04 enero-marzo ISSN impreso: 0258-5936 Ministerio de Educación Superior. Cuba ISSN digital: 1819-4087 Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Agrícolas http://ediciones.inca.edu.cu Original article Impacts of the gender strategy in the agricultural sector, through the Local Agricultural Innovation Project (PIAL) Bárbara Benítez-Fernández1* Anaisa Crespo-Morales2 Caridad Casanova3 Aliek Méndez-Bordón4 Yaima Hernández-Beltrán5 Rodobaldo Ortiz-Pérez1 Rosa Acosta-Roca1 María Isabel Romero-Sarduy6 1Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Agrícolas (INCA), carretera San José-Tapaste, km 3½, Gaveta Postal 1, San José de las Lajas, Mayabeque, Cuba. CP 32 700 2Policlínico Docente “Pedro Borrás Astorga”, Calle Comandante Cruz # 70, La Palma, Pinar del Río, Cuba 3Universidad de Cienfuegos “Carlos Rafael Rodríguez”, carretera a Rodas, km 3 ½, Cuatro Caminos, Cienfuegos, Cuba 4Universidad Las Tunas, Centro Universitario Municipal “Jesús Menéndez”, calle 28 # 33, El Cenicero, El batey, Jesús Menéndez, Las Tunas, Cuba 5Universidad de Sancti Spíritus “José Martí Pérez”. -

Artemisa & Mayabeque Provinces

File10-artemisa-mayabequ-loc-cub6.dwg Book Initial Mapping Date Road Cuba 6 AndrewS May 2011 Scale All key roads labelled?Hierarchy Hydro ChapterArtemisa-Mayabequ Editor Cxns Date Title Spot colours removed?Hierarchy Symbols Author MC Cxns Date Nthpt Masking in Illustrator done? ? Book Off map Inset/enlargement correct?dest'ns BorderLocator A1 Key none Author Cxns Date Notes Basefile Final Ed Cxns Date KEY FORMAT SETTINGS New References Number of Rows (Lines) Editor Check Date MC Check Date Column Widths and Margins MC/CC Signoff Date ©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd a rtemisa & Mayabeque p%047 r / poovincesp 883,838 Why Go? Artemisa Province. 144 Glancing from your window as you leave Havana, you will San Antonio de los see a flat, fertile plain stretching away from the capital. As Baños ..............144 far as the eye can see – west to the mountainous Sierra Artemisa ...........145 de Rosario and east to Matanzas province’s wildlife-rich Soroa ..............146 swamps – spreads a patchwork of dusty farmland and cheerful one-horse towns and hamlets. Travel-wise this has Las Terrazas ........148 been bypassed by tourists, and has instead long been the Bahía Honda ........ 151 bastion of weekending habaneros (Havana folk). Mayabeque Province 151 This could – possibly – be changing. Formerly Havana Playa Jibacoa .......152 province, this region was has been redefined in 2011 as the Jaruco .............155 all-new dual provinces of Artemisa and Mayabeque. Artemisa’s big draw is Cuba’s gorgeously situated eco- Surgidero de capital, Las Terrazas. Mayabeque beckons with beaches Batabanó ...........155 of Varadero-quality sand (without the crowds), and one of Cuba’s greatest train journeys: the delightful Hershey train, which traverses the gentle, lolling countryside to Matanzas. -

Amphibia: Anura: Eleutherodactylidae), from Eastern Cuba

124 SOLENODON 12: 124-135, 2015 Another new cryptic frog related to Eleutherodactylus varleyi Dunn (Amphibia: Anura: Eleutherodactylidae), from eastern Cuba Luis M. DÍAZ* and S. Blair HEDGES** *Museo Nacional de Historia Natural de Cuba, Obispo #61, Esquina Oficios, Plaza de Armas, Habana Vieja, CP 10100, Cuba. [email protected] **Department of Biology, 208 Mueller Laboratory, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania 16802-530, USA. [email protected] ABSTRacT. A new cryptic frog, Eleutherodactylus beguei sp. nov., is described from the pine forests of La Munición, Yateras, Guantánamo Province, Cuba. It is sympatric with E. feichtin- geri, another recently described grass frog closely related to E. varleyi, but differs in morphol- ogy, vocalization and DNA sequences of the mitochondrial Cyt-b gene. One female of the new species was found vocalizing in response to a calling male, a behavior that is still poorly documented in anurans. Same male and female were found in axillary amplexus and sur- rounded by 9 eggs (3.5–3.7 mm in diameter) 5 hours after being isolated in a small container. Key words: Amphibia, Anura, Eleutherodactylidae, Eleutherodactylus, new species, Terrarana, Euhyas, West Indies, Guantánamo, female reciprocation calls, eggs. INtrODUCtION After a recent review of the geographic variation of the Cuban Grass Frog Eleutherodactylus varleyi Dunn, Díaz et al. (2012) described E. feichtingeri, a cryptic species widely distributed in central and eastern Cuba. the two species differ primarily in tympanum size, supratympanic stripe pattern, and advertisement calls. Species recognition was also supported by genetic and cytogenetic data. One of the authors (SBH) conducted DNA sequence analyses that confirmed the existence of two species at La Munición, Humboldt National Park. -

Squamata: Tropidophiidae)

caribbean herpetology note Easternmost record of the Cuban Broad-banded Trope, Tropidophis feicki (Squamata: Tropidophiidae) Tomás M. Rodríguez-Cabrera1*, Javier Torres2, and Ernesto Morell Savall3 1Sociedad Cubana de Zoología, Cuba. 2 Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas 66045, USA. 3Área Protegida “Sabanas de Santa Clara,” Empresa Nacional para la Protección de la Flora y la Fauna, Villa Clara 50100, Cuba. *Corresponding author ([email protected]) Edited by: Robert W. Henderson. Date of publication: 14 May 2020. Citation: Rodríguez-Cabrera TM, Torres J, Morell Savall E (2020) Easternmost record of the Cuban Broad-banded Trope, Tropidophis feicki (Squa- mata: Tropidophiidae), of Cuba. Caribbean Herpetology, 71, 1-3. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31611/ch.71 Tropidophis feicki Schwartz, 1957 is restricted to densely forested limestone mesic areas in western Cuba (Schwartz & Henderson 1991; Henderson & Powell 2009). This species has been reported from about 20 localities distributed from near Guane, in Pinar del Río Province, to Ciénaga de Zapata, in Matanzas Province Rivalta et al., 2013; GBIF 2020; Fig. 1). On 30 June 2009 and on 22 December 2011 we found an adult male and an adult female Tropidophis feicki (ca. 400 mm SVL; Fig. 2), respectively, at the entrance of the “Cueva de la Virgen” hot cave (22.8201, -80.1384; 30 m a.s.l.; WGS 84; point 14 in Fig. 1). The cave is located within “Mogotes de Jumagua” Ecological Reserve, Sagua La Grande Municipality, Villa Clara Province. This locality represents the first record of this species for central Cuba, particularly for Villa Clara Province. -

The Second Wave of the COVID-19 Epidemic in Cuba: the Sixth- and Seventh-Month Flare-Ups

EDITORIAL The second wave of the COVID-19 epidemic in Cuba: the sixth- and seventh-month flare-ups Enrique Beldarraín-Chaple, MD PhD; Ileana R. Alfonso-Sánchez, PhD; María Vidal-Ledo PhD Introduction The remaining 44,067 confirmed cases (6,703 on COVID-19 is a respiratory disease caused that day) and 1,440 deaths (310 of them new) were by the SARS-CoV-2 virus. It was first diagnosed distributed among the 118 countries reporting in December 2019 in the Chinese city of Wuhan, cases of the disease.[4] Hubei province, and was found to generate In the Cuban epidemic, cases increased pneumonia different from that produced by other during March, and on April 24th, the curve reached viruses. [1] The disease was very aggressive and its acme with 849 active cases. From May contagious and spread rapidly to other Asian onwards, the number of positive cases decreased countries and the rest of the world, causing a and, although 244 cases were reported on June 7th, pandemic. On January 30th, 2020, the WHO the curve continued to decrease until mid-July, [5] declared it a global emergency. [2] which indicates an effective control of the disease The first three cases of COVID-19 in Cuba in the country. were reported on March 11th of the same year.[3] When the first cases were diagnosed, the That same day, the WHO declared 125,048 Province and Municipality Defense Councils were confirmed cases worldwide (6,729 on that day) activated. These councils are made up of decision- and 4,613 deaths (321 of them new). -

Portfolio of Opportunities for Foreign Investment 2018 - 2019

PORTFOLIO OF OPPORTUNITIES FOR FOREIGN INVESTMENT 2018 - 2019 INCLUDES TERRITORIAL DISTRIBUTION MINISTERIO DEL COMERCIO EXTERIOR Y LA INVERSIÓN EXTRANJERA PORTFOLIO OF OPPORTUNITIES FOR FOREIGN INVESTMENT 2018-2019 X 13 CUBA: A PLACE TO INVEST 15 Advantages of Investing in Cuba 16 Foreign Investment in Cuba 16 Foreign Investment in Figures 17 General Foreign Investment Policy Principles 19 Foreign Investment with agricultural cooperatives as partners X 25 FOREIGN INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITIES BY SECTOR X27 STRATEGIC CORE PRODUCTIVE TRANSFORMATION AND INTERNATIONAL INSERTION 28 Mariel Special Development Zone X BUSINESS OPPORTUNITIES IN ZED MARIEL X 55 STRATEGIC CORE INFRASTRUCTURE X57 STRATEGIC SECTORS 58 Construction Sector X FOREIGN INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY SPECIFICATIONS 70 Electrical Energy Sector 71 Oil X FOREIGN INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY SPECIFICATIONS 79 Renewable Energy Sources X FOREIGN INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY SPECIFICATIONS 86 Telecommunications, Information Technologies and Increased Connectivity Sector 90 Logistics Sector made up of Transportation, Storage and Efficient Commerce X245 OTHER SECTORS AND ACTIVITIES 91 Transportation Sector 246 Mining Sector X FOREIGN INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY SPECIFICATIONS X FOREIGN INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY SPECIFICATIONS 99 Efficient Commerce 286 Culture Sector X FOREIGN INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY SPECIFICATIONS X FOREIGN INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY SPECIFICATIONS 102 Logistics Sector made up of Water and Sanitary Networks and Installations 291 Actividad Audiovisual X FOREIGN INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY SPECIFICATIONS X -

Miami Herald Miami, Florida 19 May 2018

U.S.-Cuba Trade and Economic Council, Inc. New York, New York Telephone (917) 453-6726 • E-mail: [email protected] Internet: http://www.cubatrade.org • Twitter: @CubaCouncil Facebook: www.facebook.com/uscubatradeandeconomiccouncil LinkedIn: www.linkedin.com/company/u-s--cuba-trade-and-economic-council-inc- Miami Herald Miami, Florida 19 May 2018 More than 100 people were killed after a Boeing 737-201 on a flight from Havana to Holguín crashed and exploded in a field Friday afternoon shortly after takeoff from José Martí International Airport. In the wake of the crash, Cuba's Council of State declared two days of national mourning. State media reported that 104 passengers — 100 of them Cuban — as well as several Mexican crew members were aboard the plane that was leased by Cubana de Aviación, the Cuban national airline, from a Mexican company. The aircraft was nearly 40 years old. Four survivors were taken to Calixto Garcia hospital in Havana, but one, a man, later died from burns and other trauma, according to Granma, the Communist Party newspaper. The remaining three female survivors were in serious condition. Only one of them, Emiley Sánchez de la O, 39, of Holguín, was identified by Cuban media. An official death toll hadn't been released Friday night, but it appears that the three women may be the only crash survivors. Argentina's foreign minister said two Argentines were among the dead. Miguel Díaz-Canel, who became Cuba's president on April 19, headed to the scene after receiving word of the crash. "The news is not very hopeful. -

Portfolio of Opportunities for Foreign Investment

PORTFOLIO OF OPPORTUNITIES FOR FOREIGN INVESTMENT 2016 - 2017 PORTFOLIO OF OPPORTUNITIES FOR FOREIGN INVESTMENT 2016 - 2017 X9 CUBA: A PLACE TO INVEST 11 Advantages of investing in Cuba 12 Foreign Investment in Cuba 12 Foreign Investment Figures 13 General Foreign Investment Policy Principles 15 Foreign Investment with the partnership of agricultural cooperatives X21 SUMMARY OF BUSINESS OPPORTUNITIES 23 Mariel Special Development Zone 41 Agriculture Forestry and Foods Sector 95 Sugar Industry Sector 107 Industrial Sector 125 Tourism Sector 153 Energy Sector 173 Mining Sector 201 Transportation Sector 215 Biotechnological and Drug Industry Sector 223 Health Sector 231 Construction Sector 243 Business Sector 251 Audiovisual Sector 259 Telecomunications, Information Technologies and Communication and Postal Services Sector 265 Hydraulic Sector 275 Banking and Financial Sector X279 CONTACTS OF INTEREST Legal notice: The information in the fol- lowing specifications is presented as a summary. The aim of its design and con- tent is to serve as a general reference guide and to facilitate business potential. In no way does this document aim to be exhaustive research or the application of criteria and professional expertise. The Ministry of Foreign Commerce and In- vestment disclaims any responsibility for the economic results that some foreign investor may wish to attribute to the in- formation in this publication. For matters related to business and to investments in particular, we recommend contacting expert consultants for further assistance. CUBA: A PLACE TO INVEST Advantages of investing in Cuba With the passing of Law No. 118 and its complemen- Legal Regime for Foreign Investment tary norms, a favorable business climate has been set up in Cuba. -

“Exploring Health, Wellness & Culture in Cuba” a MEDICC Gateways

“Exploring Health, Wellness & Culture in Cuba” A MEDICC Gateways Professional Research Opportunity February 16-22, 2020 Join MEDICC for an insider’s look at intersections between health and culture in Cuba’s unique and historic capital! MEDICC welcomes all whose area of expertise and/or profession is medicine, health or wellness; as well as artists, photographers, actors, musicians and other cultural workers whose professional life includes culture as a component of health, contributing to improved social determinants of health or individual/population wellbeing. An extraordinary itinerary is in the works on the tail end of Havana’s 500th Anniversary year, including learning from participatory community projects, natural/traditional medical therapies, artists’ cooperatives, mental health centers, neighborhood family doctor-and-nurse offices, children’s theater ….and finally, the HistArtMed program that brings together Cuban health professionals and the country’s vibrant culture, past and present. Draft Program in Cuba (Subject to change) Sunday, February 16 Morning / Afternoon ARRIVAL Check-in Hotel Sevilla Morning / Afternoon Orientation Meeting: Background on Cuban social development and your program, Hotel Sevilla Afternoon / Evening Welcome Lunch or Dinner Monday, February 17 Morning Primary care in Cuba’s National Health System Visit a community-based multispecialty polyclinic and a family doctor-and-nurse office nearby. Both are accredited for teaching medical and other health professionals. Take time to talk with patients, too. -

The Mineral Industry of Cuba in 2015

2015 Minerals Yearbook CUBA [ADVANCE RELEASE] U.S. Department of the Interior May 2019 U.S. Geological Survey The Mineral Industry of Cuba By Yadira Soto-Viruet In 2015, Cuba was estimated to rank 7th (tied with the and Cuba’s Embassy reopened in Washington, DC (White House, Philippines) among the world’s leading producers of cobalt, The, 2014; U.S. Department of State, 2015; U.S. Department of which was a byproduct of nickel processing, and 10th among the the Treasury, 2015; Wacaster and others, 2015). world’s leading producers of nickel. Other mineral commodities produced in the country included bentonite, cement, crushed Minerals in the National Economy stone, feldspar, gypsum, kaolin, lime, limestone, marble, In 2015, Cuba’s real gross domestic product (GDP) nitrogen, salt, silica sand, sulfuric acid, and zeolites. Cuba also increased by 4.3% compared with that of 2014. The industrial produced crude petroleum, natural gas, and petroleum refinery manufacturing sector (excluding the sugar industry) made products. According to the Centro para la Promocion del up about 13% of the country’s GDP; the construction sector, Comercio Exterior y la Inversion Extranjera de Cuba [Center about 6%; the sector that included electricity, gas, and water, for Promotion of Foreign Trade and Investment] (CEPEC), about 1.4%; and the mining and quarrying sector, about 0.6%. the country had significant mineral resources of cobalt and Employment in the mining and quarrying sector increased by nickel and less significant mineral resources of chromium, iron 4% to 28,900 workers in 2015 compared with 27,700 workers ore, and manganese. -

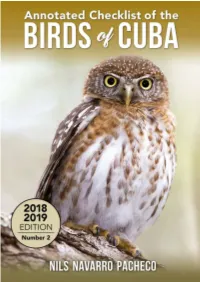

Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Cuba No. 2, 2018

ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF THE BIRDS OF CUBA Number 2 2018-2019 Nils Navarro Pacheco www.EdicionesNuevosMundos.com Senior Editor: Nils Navarro Pacheco Editors: Soledad Pagliuca, Kathleen Hennessey and Sharyn Thompson Cover Design: Scott Schiller Cover: Cuban Pygmy Owl (Glaucidium siju), Peralta, Zapata Swamp, Matanzas, Cuba. Photo Nils Navarro Pacheco, 2017 Back cover Illustrations: Nils Navarro, © Endemic Birds of Cuba. A Comprehensive Field Guide, 2015 Published by Ediciones Nuevos Mundos www.EdicionesNuevosMundos.com [email protected] Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Cuba ©Nils Navarro Pacheco, 2018 ©Ediciones Nuevos Mundos, 2018 ISBN: 9781790608690 2 To the memory of Jim Wiley, a great friend, extraordinary person and scientist, a guiding light of Caribbean ornithology. He crossed many troubled waters in pursuit of expanding our knowledge of Cuban birds. 3 About the Author Nils Navarro Pacheco was born in Holguín, Cuba. He is a freelance author and an internationally acclaimed wildlife artist and scientific illustrator. A graduate of the Academy of Fine Arts with a major in painting, he served as curator of the herpetological collection of the Holguín Museum of Natural History, where he described several new species of lizards and frogs for Cuba. Nils has been travelling throughout the Caribbean Islands and Central America working on different projects related to the conservation of biodiversity, with a particular focus on amphibians and birds. He is the author of the book Endemic Birds of Cuba, A Comprehensive Field Guide, which, enriched by his own illustrations, creates a personalized field guide structure that is both practical and useful, with icons as substitutes for texts. -

Cuba's Covid-19 Strategy: Updated Epidemic Control

CUBA’S COVID-19 STRATEGY: UPDATED EPIDEMIC CONTROL AND RECOVERY MEASURES THROUGH OCTOBER 2020 Cuba’s strategy to control and treat COVID-19 across the island block by block, to limit the impact of more broader-reaching con- continues apace, including updated measures to confront the tainment measures. The aim of the gradual, targeted re-opening epidemic and a multi-phase recovery process. Together, these plan is to prevent transmission to larger swaths of the popula- intersectoral measures form a part of the country’s COVID-19 tion while mitigating effects on the economy and daily life, which Prevention and Control Plan—approved in February 2020 and have been severely exacerbated by recent tightening of the US regularly updated—and are fundamental for controlling transmis- embargo. sion and helping to smooth the diffi cult socio-economic transition as the island re-opens. As in previous phases, the reopening Following the set of detailed charts of measures published in strategy relies on analyzing epidemiological data on national, our April and July issues, MEDICC Review continues to docu- provincial and municipal levels to determine what measures ment Cuba’s process and strategies for facing the pandemic with should be taken, where, and when. This level of analysis identi- this timeline of the measures taken from August through Octo- fi ed events of local outbreaks in different provinces in August ber and others outlining the POS-COVID-19 phases. For earlier and September resulting in a reversion to earlier, more restrictive periods, see: https://mediccreview.org/cubas-covid-19-strategy measures in some areas.