The Louisiana Regional Restoration Planning Program January 2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Waterfowl Rely on Catahoula Lake in Central Louisiana Enforcement of New Clean Water Rule Still Unclear for Farmers

New Sorghum Pest Youth Wetlands Program Water and Food Safety page 12 page 20 page 26 Vol. 58, No. 3, Summer 2015 Waterfowl rely on Catahoula Lake in central Louisiana Enforcement of new Clean Water Rule still unclear for farmers Olivia McClure EDITORIAL BOARD: John S. Russin, Chairman Although a rule that revises which bodies of water are subject to Clean Water Linda Foster Benedict Act regulations has taken effect, the agricultural community continues to be Michael Blazier Rick Bogren concerned about how strict federal scrutiny will be. Melissa Cater Agricultural water has always been Glen T. Gentry exempt from Clean Water Act regulations, Kurt M. Guidry but the new Clean Water Rule incorporates Dustin Harrell Claudia Husseneder several types of water that were never reg- Kathy Kramer ulated before and are common on farms. Megan La Peyre Tributaries and waterways adjacent or connected to a previously jurisdictional EDITOR: Linda Foster Benedict waterway must now comply with the Clean ASSOCIATE EDITOR: Rick Bogren Water Act, said LSU AgCenter economist DESIGNER: Kathy Kramer Naveen Adusumilli. Drainage ditches and PHOTO EDITOR: John Wozniak CONTRIBUTORS: Tobie Blanchard, Craig irrigation runoff, for example, are not Gautreaux, Randy LaBauve, Elma Sue specifically regulated by the act but drain McCallum, Olivia McClure and Bruce Schultz into those that are. WEB DESIGN: Ronda Clark and Kathy Kramer “Can farmers dig a ditch now, and how Louisiana Agriculture is published quarterly by will it be regulated? It is unclear right now,” the Louisiana Agricultural Experiment Station. Subscriptions are free. You may also subscribe Adusumilli said. to a Web version of the magazine, which is The changes are spelled out in the available at www.LSUAgCenter.com. -

AEP's 2017 GRI Report

For more information contact: Sandy Nessing Managing Director Corporate Sustainability American Electric Power [email protected] Melissa Tominack Sr. Sustainability Coordinator American Electric Power [email protected] 2 American Electric Power –2017 GRI Report 2017 Global Reporting Initiative AEP follows the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) G4 reporting principles in terms of data quality, report content and organizational boundaries. This report was developed according to the fourth generation of GRI’s Sustainability Reporting Guidelines, otherwise known as G4, in accordance with a core adherence level. The GRI guidelines provide a voluntary reporting framework used by organizations around the world as the basis for sustainability reporting. We also responded using the Electric Utility Sector Supplement for reporting on industry-specific information. G4 Description Report Location Indicator Strategy and Analysis Message from the G4-1 Statement from the most senior decision-maker Chairman 2016 Form 10-K Risk Factors pg. 33 G4-2 Description of key impacts, risks, and opportunities Managing Risk Carbon Profile Analysis Strategy for Growth Organizational Profile G4-3 Name of the organization See homepage G4-4 Primary brands, products, and/or services About Us Columbus, OH G4-5 Location of organization’s headquarters About Us G4-6 Countries in which the company has operations About Us G4-7 Nature of ownership and legal form 2016 Form 10-K pg. 1 G4-8 Markets served 2016 Form 10-K pg. 1 G4-9 Scale of the reporting organization About AEP 17,634 (see appendix G4-10 Total number of employees by employment contract & gender 1) G4-11 Total employees covered by collective bargaining agreements Labor Relations Significant changes in organizations size, structure, ownership, or its G4-13 2016 Form 10-K pg. -

The Ramsar Convention on Wetlands

NATIONAL WETLANDS NEWSLETTER, vol. 29, no. 2. Copyright © 2007 Environmental Law Institute.® Washington D.C., USA.Reprinted by permission of the National Wetlands Newsletter. To subscribe, call 800-433-5120, write [email protected], or visit http://www.eli.org/nww. The Ramsar Convention on Wetlands: Assessment of International Designations Within the United States The Ramsar Convention is an international framework used to protect wetlands. At this time, the United States has 22 designated sites listed as wetlands of international importance. In this Article, the authors analyze survey data collected from each of these 22 sites to determine whether and how Ramsar designation benefits these wetland areas. BY ROYAL C. GARDNER AND KIM DIANA CONNOLLY ssues related to wetlands and wetland protection often involve engage in international cooperation.6 Its nonregulatory approach boundaries. Sometimes the lines are drawn on the ground, has led some to ask what benefits are associated with Ramsar des- delineating between so-called “jurisdictional” wetlands and ignation. For example, the United States has a maze of federal, uplands. Sometimes the boundaries are conceptual: trying state, and local laws that protect wetlands, so does the international Ito determine the proper relationship between the federal and state recognition of a site provide any additional returns? To answer governments with respect to wetland permits, or trying to balance this question, we surveyed all 22 U.S. Ramsar sites.7 Although the the need to protect the aquatic environment without inappropri- results varied from site to site, we found that Ramsar designation ately limiting activities on private property. Other times interna- adds some value to all sites. -

50660 Federal Register / Vol. 62, No. 187 / Friday, September 26, 1997 / Rules and Regulations

50660 Federal Register / Vol. 62, No. 187 / Friday, September 26, 1997 / Rules and Regulations DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR 6 supplement also provided detailed 1996±97 late-season frameworks. For information on the 1997±98 regulatory those topics where a Council Fish and Wildlife Service schedule and announced the Service recommendation is not shown, the Migratory Bird Regulations Committee Council supported continuing the same 50 CFR Part 20 and Flyway Council meetings. On June frameworks as in 1996±97. RIN 1018-AE14 27, 1997, the Service held a public hearing in Washington, DC, as General Migratory Bird Hunting; Final announced in the March 13 and June 6 Written Comments: The Humane Frameworks for Late-Season Migratory Federal Registers to review the status of Society of the United States (Humane Bird Hunting Regulations migratory shore and upland game birds. Society) expressed concern that the The Service discussed hunting public was not well represented in the AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, regulations for these species and for regulations-development process and Interior. other early seasons. On July 23, 1997, requested establishment of a system ACTION: Final rule. the Service published in the Federal directly involving the non-hunting Register (62 FR 39712) a third public. In addition, they recommended SUMMARY: This rule prescribes final late- document. This document contained the that the Service undertake efforts to season frameworks from which States final regulatory alternatives for the obtain population estimates for all may select season dates, limits, and 1997±98 duck hunting season and the hunted species. Finally, they other options for the 1997±98 migratory proposed early-season frameworks for recommended pre-sunrise shooting be bird hunting season. -

Ramsar Convention on Wetlands of International Importance

The Convention on Wetlands of International Importance Ramsar Convention What Ramsar Is: Who can nominate a site stakeholders associated with the proposed site greatly contribute to • In 1971, an international convention • Any local government, group, the nomination process; and was held in Ramsar, Iran and community, private organization, participants signed a treaty entitled, or landowner can nominate a A completed Ramsar Information “The Convention on Wetlands of site for inclusion on the Ramsar Sheet, is available online at http://bit. International Importance, Especially List of Wetlands of International ly/1HIU7PR as Waterfowl Habitat.” Importance. The Federal government can also nominate sites, such as Nine Criteria for “Wetlands • The Ramsar Convention provides a National Parks, National Forests, or of International Importance” framework for voluntary international National Wildlife Refuges. Designation: cooperation for wetland conservation. A wetland should be considered • A written agreement is required internationally important if it meets • The U.S. acceded to the Ramsar from all landowners and a Member Convention April 18, 1987. any one of the following criteria. The of Congress representing the site: geographic area. What Ramsar Does: 1. contains a representative, rare, • Recognizes wetlands’ importance to Nomination package or unique example of a natural communities, cultures, governments, The petitioner must submit a complete or near-natural wetland type and businesses and encourages nomination package to the Director, found within the appropriate wetland conservation and wise use of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), biogeographic region; or wetlands. 1849 C Street, NW, Washington, D.C. 20006, with a copy to the Global 2. supports vulnerable, endangered, • Establishes criteria for designating Program, Division of International or critically endangered species rivers, marshes, coral reefs and other Conservation, FWS. -

Fish Consumption and Swimming Advisories Related Primarily To

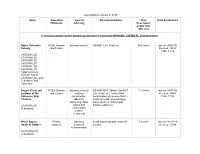

Last updated January 2, 2019 Name Causative Type of Recommendations Area Date Established Pollutants Advisory Description and/or Size Affected Fish Consumption and/or Swimming Advisories Caused by ORGANIC CHEMICAL Contamination Upper Calcasieu PCBs, Dioxins Advisory crab fat DO NOT EAT Crab Fat 56.6 miles Issued: 04/07/92 Estuary and Furans Revised: 10/94, 1995, 11/16 LA030301_00 LA030302_00 LA030303_00 LA030304_00 LA030401_00 LA030402_00 (Approximately northern half of LA030402_00, only) (Calcasieu and Cameron) Bayou d'Inde and PCBs, Dioxins Advisory crab fat DO NOT EAT Catfish. DO NOT 11.8 miles Issued: 04/07/92 portions of the and Furans and fish EAT Crab Fat. Fish/shellfish Revised: 10/94, Calcasieu Ship consumption; consumption of no more than 2 1995, 11/16 Channel advisory meals a month; no swimming, swimming, water water sports & contact with LA030901_00 sports and bottom sediments (Calcasieu) contact with bottom sediments Olsen Bayou Priority Advisory Avoid swimming and sediment 7.3 miles Issued: 01/17/89 south of Carlyss organics sediment contact. Revised: 10/94 contamination LA030304_001 (Calcasieu) Name Causative Type of Recommendations Area Date Established Pollutants Advisory Description and/or Size Affected Bayou Bonfouca Poly-aromatic Advisory Avoid swimming or sediment 12.3 miles Issued: 11/24/87 hydrocarbons swimming contact Revised: 12/10/98 LA040907_00 (PAH), LA040908_00 benzo(a) LA040917_00 (St. pyrene Tammany) (creosote) Devil's Swamp, Fish Advisory Advisory fish Do not eat fish or crawfish from 24 acres Issued: 07/09/93 Devil's Swamp for PCBs, consumption; this area Revised: 08/12/15 Lake, and Bayou mercury advisory Baton Rouge swimming Avoid swimming Swimming LA070203_00 (East advisory for Baton Rouge) Hexachloroben -zene, Hexachlorobut- adiene, Arsenic, Lead, Mercury Capitol Lake Priority Advisory fish No fish consumption. -

Water Resources of the Little River Basin, Louisiana

Water Resources of the Little River Basin, Louisiana By M. W. GAYDOS, J. E. ROGERS, and R. P. SMITH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1989 Prepared in cooperation with the Louisiana Department of Public Works and the Louisiana Geological Survey Department of Conservation, Baton Rouge, Louisiana UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON 1973 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ROGERS C. B. MORTON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY V. E. McKelvey, Director Library of Congress catalog-card No. 73-600030 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents. U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price J3.15 (paper cover) Stock Number 2401-02416 CONTENTS Page Abstract ______________ _ ____________ 1 Acknowledgments _ - - ______-_-- - 2 Introduction __ 2 The hydrologic setting __ _____ ______ 4 Summary of geology _ .. 4 Topography and drainage _ ________________ 6 Water use _______ _ ___________ 7 Hydrologic zones _________ ________ 8 Zone A ______ _ 9 Streams 9 Aquifers 11 Suitability of water _ _ _ 16 Zone B _____________________________ _ ____ 19 Streams _-_-_ _ _____________ _ _ 19 Aquifers __________ ___________ _ _ 20 Suitability of water ________________________ 22 Zone C ____________________________________ 23 Streams 23 Aquifers ______________________________- 24 Suitability of water ________________________ 29 Water conditions at population centers __ _ 30 Ruston _______ ____________ 31 Jonesboro-Hodge _ _ _ _ _____________ 34 Winnfield __________________________________ 35 Tullos-Urania-Olla _____________________________ -

Caddo Lake Watershed and Environmental Flows

Caddo Lake Watershed And Environmental Flows Red River Valley Association Meeting June 1, 2016 Richard Lowerre Caddo Lake Institute Focus on Talk Why and How of Restoring and Protecting Instream Flows For Environmental Purposes Caddo Lake Watershed Natural History of Caddo Lake The Great Raft on the Red River About 100 Miles Long, Moving 1 Mile/Year CADDO LAKE INSTITUTE Founded in 1992 by Don Henley A nonprofit corporation for scientific and educational purposes To assist the communities of Caddo Lake to protect the Lake, wetlands and watershed. Ramsar designation Caddo Lake National Wildlife Refuge Protection of Instream or Environmental Flows www.caddolake.us What We Try to Do Assist the local communities with protection of Caddo Lake and thus, its watershed. Obtain Ramsar designation. Convert the Army ammunition plant to a wildlife refuge. Protect the water quality Address the problems of invasive species Assure adequate flows - amount and timing - to Caddo The Ramsar Convention on Wetlands Signed in Ramsar, Iran in 1971 Over 160 Countries Have Joined Over 2000 wetland designated “Wetlands of International Importance,” with 160 million hectares Caddo Lake designated in 1993 U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, International Affairs 1. Izembek National Wildlife Refuge(NWR) 2. Forsythe NWR 3. Okefenokee NWR 4. Ash Meadows NWR 5. Everglades National Park 6. Chesapeake Bay Estuarine Complex 7. Cheyenne Bottoms 8. Cache-Lower White Rivers 9. Horicon Marsh 10. Catahoula Lake 11. Delaware Bay Estuary 12. Pelican Island NWR 13. Caddo Lake 14. Connecticut River Estuary 15. Cache River-Cypress Creek Wetlands 16. Sand Lake NWR 17. Bolinas Lagoon 18. -

Louisiana 2021-2022 Hunting & Wma Regulations

LOUISIANA 2021-2022 HUNTING & WMA REGULATIONS E-LICENSE COMING SOON! PassThe Down Hunt OutfittingOutfitting The Hunt SeriousSerious The StartsTradition SportsmenSportsmen Starts SinceSince HereHere 19671967 The Best Firearm The Best FirearmSelection in SelectionSouth in Louisiana South Louisiana • Archery • Archery • Clothing • Clothing • Footwear • Footwear• Knives • Knives Knowledgeable Staff Knowledgeable Staff FINANCING FINANCINGAVAILABLE! AVAILABLE! 3520 Ambassador Caffery Pkwy u Lafayette, LA 70503 u (337) 988-1191 www.LAFAYETTESHOOTERS.com 3520 Ambassador Caffery Pkwy u Lafayette, LA 70503 u (337) 988-1191 www.LAFAYETTESHOOTERS.com 3520 Ambassador Caffery Pkwy Lafayette, LA 70503 (337) 988-1191 www.LAFAYETTESHOOTERS.com CONTENTS Cover photo: Michael Shakes, Shutterstock.com 4. MAJOR CHANGES FOR 2021-2022 6. LICENSING 10. GENERAL HUNTING INFORMATION Hunter Education Requirements ��������������������������10 LDWF Field Office/Enforcement Office Numbers����������11 12. DEER HUNTING Chronic Wasting Disease Regulations��������������������12 Deer Area Schedules & Descriptions ��������������������13 Deer Tagging Information �������������������������������������18 Deer Hunting Regulations ������������������������������������19 23. QUADRUPEDS & RESIDENT GAME BIRDS Schedules �������������������������������������������������������������23 Methods of Take ���������������������������������������������������24 26. TURKEY Turkey Area Schedules & Descriptions �����������������26 Turkey Hunting Regulations����������������������������������27 -

Ramsar Site Wetlands of International Importance

Ramsar Site Wetlands of International Importance awainui and Hämäkua @Marsh Complex in Kailua, O‘ahu was designated a Ramsar site in February 2005. Sacred to Hawaiians, Kawainui Marsh is the largest remaining emergent wetland in Hawai‘i and the state’s largest ancient freshwater fishpond. Located in the center of the caldera of the Ko‘olau shield volcano, the marsh today provides primary habitat for four of Hawai‘i’s endemic and endangered waterbirds. The marsh stores surface water and provides flood protection for Kailua town. Ramsar Hämäkua Marsh is a smaller wetland that is historically connected to the adjacent Kawainui Marsh. It also provides significant habitat for Hawai‘i’s endangered waterbirds. ostering worldwide wetland conservation is ;the primary goal of the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands. First signed in 1971, this international treaty promotes conservation activities that also incorporate human use. Participation in the Convention brings nations together to improve wetland management for the benefit of people and wildlife and promote biological diversity. www.ramsar.org www.ramsarcommittee.us he Ramsar designation for the IKawainui and Hämäkua Marsh Complex was accomplished through the efforts of many community groups, especially Hawaii’s Thousand Friends, and government agencies, such as U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. • Kawainui-Hämäkua Marsh is the largest existing wetland in Hawai‘i, encompassing 850 acres from Maunawili Valley toward Kailua Bay. • Kawainui was developed as a 450- he Ramsar Convention on Wetlands of International acre fishpond by the Hawaiians Importance promotes wetland conservation throughout the who settled the Kailua ahupua‘a. T world. There are more than 1,600 Ramsar sites in over 150 • The Kawainui-Hämäkua Marsh countries, including 22 sites in the U.S. -

Catahoula National Wildlife Refuge Hunting and Fishing Regulations 2019-2020

The Refuge constitute a violation of refuge regulations. One adult may U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Catahoula National Wildlife Refuge, located in east central supervise two youth during small game and waterfowl hunts Louisiana, 12 miles east of Jena, was established on but only one during big game hunts. October 28, 1958 and now totals 25,242 acres. Permits The 6,671 acre Headquarters Unit borders nine miles of An annual Special Recreational Activity Permit is Catahoula the northeast shore of Catahoula Lake. The 18,571 acre required for all hunters and fisherman 16 years old and Bushley Bayou Unit, located eight miles west of Jonesville, older, and for all terrain vehicle (ATV) use on the refuge. National Wildlife was established May 16, 2001. The acquisition was made The Central LA NWR (20.00) Special Recreational Activity possible through a partnership agreement between The Permit applies to all refuges within the complex (Lake Refuge Hunting and Conservation Fund, American Electric Power, and the Fish Ophelia, Grand Cote, and Catahoula). and Wildlife Service. Permits are available at the Refuge Headquarters located Fishing Regulations Catahoula NWR is now part of the Central Louisiana at Grand Cote National Wildlife Refuge, seven miles west Refuges Complex administered out of the Grand Cote of Marksville, LA on Highway 1194. Permits my also be 2019-2020 NWR Headquarters Office located at: purchased at the Catahoula NWR Office, located on US 401 Island Road, Marksville, LA 71351 Highway 84, approximately 12 miles east of Jena, LA, and 318/253 4238 one mile west of the junction of highways US 84 and LA 28. -

Waterfowl and Shorebirds

6 Waterfowl and Shorebirds Description Tule Greater White-Fronted Goose The tule goose is one of two subspecies of greater white- Anser albifrons gambelli fronted geese that breed in Alaska and winter primarily Dennis R. Becker in California (Swarth and Bryant 1917); the Pacific greater white-fronted goose is the other subspecies. Introduction Populations of the Pacific goose are far greater than the tule goose. The overall size of the tule goose is generally The tule greater white-fronted goose or tule goose was larger than the Pacific goose, although there may be over- selected to represent the geese and swans group which lap between the subspecies. The tule goose has a length also includes Pacific greater white-fronted goose (Anser to 34 inches (86 cm) and wing span to 65½ inches (167 albifrons frontalis), Canada goose (Branta canadensis), cm) (Cogswell 1977). They are a medium-sized dark Aleutian Canada goose (B.c. leucopareia), lesser snow goose with the brown colors of the head and neck the goose (Chen caerulescens), and tundra swan (Cygnus same as the body and wings. Tule geese are a much columbianus). darker brown than Pacifics. Adults have a white forehead Tule geese are primarily associated with managed and black blotched belly. In most tules, the forehead may wetlands and agriculture lands. The Suisun subregion show some orange coloration. Their feet are yellow and is one of only a few important wintering areas in Cali- their bills are pink to orangish in color. Immatures do fornia. The geese/swan group is of economic and recre- not have black blotched bellies.