Paper Airplanes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

6.2 Understanding Flight

6.2 - Understanding Flight Grade 6 Activity Plan Reviews and Updates 6.2 Understanding Flight Objectives: 1. To understand Bernoulli’s Principle 2. To explain drag and how different shapes influence it 3. To describe how the results of similar and repeated investigations testing drag may vary and suggest possible explanations for variations. 4. To demonstrate methods for altering drag in flying devices. Keywords/concepts: Bernoulli’s Principle, pressure, lift, drag, angle of attack, average, resistance, aerodynamics Curriculum outcomes: 107-9, 204-7, 205-5, 206-6, 301-17, 301-18, 303-32, 303-33. Take-home product: Paper airplane, hoop glider Segment Details African Proverb and Cultural “The bird flies, but always returns to Earth.” Gambia Relevance (5min.) Have any of you ever been on an airplane? Have you ever wondered how such a heavy aircraft can fly? Introduce Bernoulli’s Principle and drag. Pre-test Show this video on Bernoulli’s Principle: (10 min.) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bv3m57u6ViE Note: To gain the speed so lift can be created the plane has to overcome the force of drag; they also have to overcome this force constantly in flight. Therefore, planes have been designed to reduce drag Demo 1 Use the students to demonstrate the basic properties of (10 min.) Bernoulli’s Principle. Activity 2 Students use paper airplanes to alter drag and hypothesize why (30 min.) different planes performed differently Activity 3 Students make a hoop glider to understand the effects of drag (20 min.) on different shaped objects. Post-test Word scramble. (5 min.) https://www.amazon.com/PowerUp-Smartphone-Controlled- Additional idea Paper-Airplane/dp/B00N8GWZ4M Suggested Interpretation of Proverb What comes up must come down Background Information Bernoulli’s Principle Daniel Bernoulli, an eighteenth-century Swiss scientist, discovered that as the velocity of a fluid increases, its pressure decreases. -

The Four Forces of Flight

1 Aviation For Kids: A Mini Course For Students in Grades 2-5 Adopted from AvKids for use by the EAA The AvKids Program developed by the National Business Aviation Association (NBAA) represents what may be the best short course in aviation science for students in grades 2-5. The following pages represents a slightly modified version of the program, with additions and deletions to provide the best activities for the development of the four forces of flight. In addition, follow up activities included involve team work problem solving in geography, writing, and mathematics. In addition, what may be the best aviation glossary for young students has been included. Topics Covered in The Mini-Course 1. The Four Forces of Flight 2. Thrust 3. Weight 4. Drag 5. Lift 6. The Main Parts of a Plane 7. Business Aviation: An Extension of General Aviation 8. Additional Aviation Projects 9. Aviation Terms 2 The Four Forces of Flight An aircraft in straight and level, constant velocity flight is acted upon by four forces: lift, weight, thrust, and drag. The opposing forces balance each other; in the vertical direction, lift opposes weight, in the horizontal direction, thrust opposes drag. Any time one force is greater than the other force along either of these directions, an acceleration will result in the direction of the larger force. This acceleration will occur until the two forces along the direction of interest again become balanced. Drag: The air resistance that tends to slow the forward movement of an airplane due to the collisions of the aircraft with air molecules. -

Pandemic Hastens the End of Jumbo Jets

ISSN 2667-8624 VOLUME 2 - ISSUE 6 - YEAR 2020 FINANCIAL REVIEW RISK & RECOVERY IN THE AVIATION INDUSTRY PANDEMIC HASTENS THE END OF JUMBO JETS AIR CARGO PERFORMANCE WILL THE B747 PLAY A OF AIRPORTS IN KEY ROLE IN VACCINE TURKEY DURING THE DISTRUBITION? NORMALIZATION PROCESS BUSINESS COCKPIT FUTURE TECH INTERVIEWS SPACEX’S DEMO-2 WITH SCOTT NEAL MISSION - THE FUTURE OF SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT COMMERCIAL SPACE GULFSTREAM VOLUME 2 - YEAR 2020 - ISSUE 6 contents ISSN 2667-8624 Publisher & Editor in Chief Managing Editor Ayşe Akalın Cem Akalın [email protected] cem.akalin@aviationturkey. com International Relations & Advertisement Director Administrative Şebnem Akalın Coordinator sebnem.akalin@ Yeşim Bilginoğlu Yörük aviationturkey.com y.bilginoglu@ aviationturkey.com Chief Advisor to Editorial Board Editors Can Erel / Aeronautical Muhammed Yılmaz/ Engineer Aeronautical Engineer Translation İbrahim Sünnetçi Tanyel Akman Şebnem Akalin Saffet Uyanık 14 Proof Reading & Editing Mona Melleberg Yükseltürk Photographer Sinan Niyazi Kutsal Graphic Design Risk and Gülsemin Bolat İmtiyaz Sahibi Recovery in Görkem Elmas Hatice Ayşe Evers Advisory Board Basım Yeri the Aviation Aslıhan Aydemir Demir Ofis Kırtasiye Industry Serdar Çora Perpa Ticaret Merkezi B Blok Renan Gökyay Kat:8 No:936 Şişli / İstanbul Lale Selamoğlu Kaplan 8 Tel: +90 212 222 26 36 Assoc. Prof. Ferhan Kuyucak demirofiskirtasiye@hotmail. Şengür com Pandemic Adress www.demirofiskirtasiye.com Administrative Office Hastens the Basım Tarihi DT Medya LTD.STI Ağustos - Eylül 2020 İlkbahar Mahallesi Galip End of Jumbo Erdem Caddesi Sinpaş Yayın Türü Jets Altınoran Kule 3 No:142 Süreli Çankaya Ankara/Turkey Tel: +90 (312) 557 9020 [email protected] www.aviationturkey.com © All rights reserved. -

(NOT) JUST for FUN Be Sure to Visit Our Logic Section for Thinking Games and Spelling/Vocabulary Section for Word Games Too!

(NOT) JUST FOR FUN Be sure to visit our Logic section for thinking games and Spelling/Vocabulary section for word games too! Holiday & Gift Catalog press down to hear him squeak. The bottom of A new full-color catalog of selected fun stuff is each egg contains a unique shape sort to find the available each year in October. Request yours! egg’s home in the carton. Match each chick’s 000002 . FREE eyes to his respective eggshell top, or swap them around for mix-and-match fun. Everything stores TOYS FOR YOUNG CHILDREN easily in a sturdy yellow plastic egg carton with hinged lid. Toys for Ages 0-3 005998 . 11.95 9 .50 Also see Early Learning - Toys and Games for more. A . Oball Rattle & Roll (ages 3 mo+) Activity Books Part O-Ball, part vehicle, these super-grabba- ble cars offer lots of play for little crawlers and B . Cloth Books (ages 6 mo .+) teethers. The top portion of the car is like an These adorable soft cloth books are sure to ☼My First Phone (ages 1+) O-ball, while the tough-looking wheels feature intrigue young children! In Dress-Up Bear, the No beeps or lights here: just a clever little toy rattling beads inside for additional noise and fun. “book” unbuttons into teddy bear’s outfit for the to play pretend! Made from recycled materials Two styles (red/yellow and (green/blue); if you day. The front features a snap-together buckle by PLAN toys, this phone has 5 colorful buttons order more than one, we’ll assort. -

Paper Winglets

Paper Winglets Objective: To test the design of a paper airplane with and without winglets. National Education Standards Grade Level: 9-12 Science 2a, 3d, 6a, 6b Subject(s): Science, Technology Prep Time: < 10 minutes Mathematics Duration: 50 minutes Technology Materials Category: Classroom (ISTE) Technology 3a, 3b, 3d, 8, 11a, 11d (ITEA) Geography Materials: • Copy paper • Construction paper • Ruler Related Link(s): How To Build A Paper Jet Model http://www.grc.nasa.gov/WWW/K-12/WindTunnel/Activities/foldairplane.html Simple Paper Airplane http://edu.larc.nasa.gov/fdprint/a9.html Supporting NASAexplores Article(s): Taming Twin Tornados http://www.nasaexplores.com/show2_articlea.php?id=02-025 Teacher Sheet(s) Page 1 of 3 www.NASAexplores.com Paper Winglets Teacher Sheet(s) Guidelines 1. Read the 9-12 NASAexplores article, “Taming Twin Tornados.” Ask a student to describe or define the term vortex. Ask the student to explain how a vortex can affect an airplane. 2. Divide students into groups of two to three. Distribute the materials. 3. Have students fly their planes in the gym, hallway, or other large indoor area (to eliminate wind effects), each time trying for maximum distance. Stress trying to duplicate the same launch angle and speed. Discussion / Wrap-up 1. Have each student write a summary of experimental results and relate the variables tested. 2. Allow each group to make a presentation on their airplane and what made its design successful. 3. Discuss the following questions with the students. a) How does plane’s weight affect flight? The weight in the airplane needs to be centered forward. -

Dept. of Aerospace Engineering

DEPT. OF AEROSPACE ENGINEERING LIST OF NEW COURSES S.No Code No. Name of the Course L T P Credits Navigation, Guidance and Control of Aerospace 1 18AE2025 3 0 0 3 Vehicles 2 18AE2026 Aircraft Instrumentation & Avionics Laboratory 0 0 3 1.5 3 18AE2027 Heat and Mass Transfer 3 0 0 3 4 18AE2028 Computational Fluid Dynamics 3 0 0 3 5 18AE2029 Computational Fluid Dynamics Laboratory 0 0 2 1 6 18AE2030 Wind tunnel Techniques 3 0 0 3 7 18AE2031 Helicopter Aerodynamics 3 0 0 3 8 18AE2032 Finite Element Analysis 3 0 0 3 9 18AE2033 Finite Element Analysis Laboratory 0 0 2 1 10 18AE2034 Theory of Elasticity 3 0 0 3 11 18AE2035 Design and Analysis of Composite Structures 3 0 0 3 12 18AE2036 Introduction to Non Destructive Testing 3 0 0 3 13 18AE2037 Structural Vibration 3 0 0 3 14 18AE2038 Aeroelasticity 3 0 0 3 15 18AE2039 Cryogenic Propulsion 3 0 0 3 16 18AE2040 Rocket and Missiles 3 0 0 3 17 18AE2041 Advanced Space Dynamics 3 0 0 3 18 18AE2042 Air Traffic Control and Aerodrome Details 3 0 0 3 19 18AE2043 Aircraft Systems 3 0 0 3 20 18AE2044 Basics of Acoustics 3 0 0 3 21 18AE2045 Basics of Aerospace Engineering 3 0 0 3 22 18AE3001 Advanced Aerodynamics 3 0 0 3 23 18AE3002 Advanced Aerodynamics Laboratory 0 0 2 1 24 18AE3003 Aerospace Propulsion 3 0 0 3 25 18AE3004 Aero Propulsion Laboratory 0 0 2 1 26 18AE3005 Orbital Space Dynamics 3 0 0 3 27 18AE3006 Flight Mechanics 3 1 0 4 28 18AE3007 Aerospace Structural Analysis 3 0 0 3 29 18AE3008 Aerospace Structural Analysis Laboratory 0 0 2 1 30 18AE3009 Flight Control Systems 3 0 0 3 31 18AE3010 Flight -

Aviation for Kids: a Mini Course for Students in Grades 2-5 Adopted from Avkids for Use by the EAA

Aviation For Kids: A Mini Course For Students in Grades 2-5 Adopted from AvKids for use by the EAA The AvKids Program developed by the National Business Aviation Association (NBAA) represents what may be the best short course in aviation science for students in grades 2-5. The following pages represent a slightly modified version of the program, with additions and deletions to provide the best activities for the development of the four forces of flight. In addition, follow up activities included involve team work problem solving in geography, writing, and mathematics. In addition, what may be the best aviation glossary for young students has been included. Topics Covered in The Mini-Course 1. The Four Forces of Flight 2. Thrust 3. Weight 4. Drag 5. Lift 6. The Main Parts of a Plane 7. Business Aviation: An Extension of General Aviation 8. Additional Aviation Projects 9. Aviation Terms Revised Dec. 2015 The Four Forces of Flight An aircraft in straight and level, constant velocity flight is acted upon by four forces: lift, weight, thrust, and drag. The opposing forces balance each other; in the vertical direction, lift opposes weight, in the horizontal direction, thrust opposes drag. Any time one force is greater than the other force along either of these directions, an acceleration will result in the direction of the larger force. This acceleration will occur until the two forces along the direction of interest again become balanced. Drag: The air resistance that tends to slow the forward movement of an airplane due to the collisions of the aircraft with air molecules. -

Airplane Explorations

Airplane explorations Children are fascinated with airplanes. This Older children may enjoy making planes that the youngest children in fascination can be a doorway to rich STEM the program can play with. Young preschoolers may need assistance (science, technology, engineering, and math) folding their planes. Toddlers will enjoy chasing after planes thrown learning even for the youngest children. When by older people and bringing them back for another flight. Allow outdoors, encourage children to slow down children to decorate and personalize the paper prior to folding the and observe the sky. Look for clouds, birds, design. More experienced children can tackle folding designs for and planes. Notice wind speed and direction. specific flight outcomes. Track contrails. Invite children to move their bodies like imaginary airplanes. These can be 1. Fold the paper vertically and then open sources of inspiration for young aviators. to create a center line. 2 Inventors of early flying machines often 2. Fold the top corners down to meet the were inspired by nature. “The invention of center (1). Fold the top corners down a 1 the modern airplane… depended upon the second time to meet the center (2). You now have the wings and nose of the scientific analysis of the anatomy of bird wings A plane. (A) and the invention of the internal combustion engine.” (Bellis 2015 Gliders) Both Leonardo 3. Fold the tip of the nose up and back towards the center. (B) da Vinci and the Wright brothers hoped to replicate the flight of winged animals like bats 4. Fold the wings together, flattening the plane. -

ENGINEERING THESIS Experimental Analysis of Paper Plane Flight

THE UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND ENGINEERING THESIS Experimental Analysis of Paper Plane Flight Characteristics Author: Natalia COOK, 43181737 Course Code: MECH4501 Supervisor: Dr Alexander Klimenko Submission date: 2nd June 2017 A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Bachelor of Engineering degree in Mechanical Engineering UQ Engineering Faculty of Engineering, Architecture and Information Technology ABSTRACT Although the concept of paper planes appears at first straight forward, understanding how the best planes can be made is a difficult and dynamic problem. They possess unstable aerodynamics, and beyond the point of launch they experience entirely uncontrolled flight. These factors compound to create a problem without a simple formulaic answer. The purpose of this project was to reach a scientific understanding of how paper aeroplanes behave, and the design characteristics required to attain predictable flight trajectories. A series of rigorous scientific experiments was established in order to gain insight into the behaviour of paper aeroplanes. After assessing the literature available that pertained to both the flight mechanisms of real aircraft and paper aircraft, it was determined that the best approach to the problem would be to iteratively test the design characteristics linked to the stability modes – longitudinal, directional and lateral – associated with flight. A total of twenty plane designs were tested with measurements taken of their distance and air time, which were used to characterise each design’s overall performance. Of these designs, the best performing were analysed to determine which of their design characteristics contributed to their superior performance. The findings of this analysis suggested a strong correlation between the fuselage depth and the flight performance of the tested paper planes. -

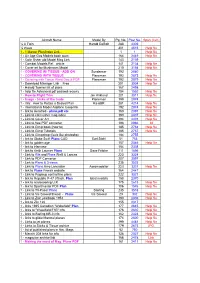

Plans Index June 22Nd

Aircraft Name Model By Pg. No. Post No. Span (inch) ½ A Twin Harold DeBolt 288 4309 ½ Wave 301 4515 Help file 1 - 1 Master Plan Index Link - 1 1 Help file 1 - Air Age Gas Models book scan 164 2449 Help file 1 - Colin Usher old Model Mag Link 143 2139 1 - Combat Models Ref. article 141 2104 Help file 1 - Cover art for Mushroom Model 210 3154 Help file 1 - COVERING W/ TISSUE - ADD ON Sundancer 192 2880 1 - COVERING WITH TISSUE Planeman 192 2873 Help file 1 - Covering with Tissue Word Doc.& PDF Planeman 192 2879 Help file 1 - Download Manager Link Free 201 3004 Help file 1 - Harold Towner list of plans 167 2498 1 - help file Advanced pdf passwd recovry 104 1552 Help file 1 - How-to Flight Trim Jim Kirkland 201 3011 Help file 1 - Image - tricks of the trade Planeman 199 2974 1 - Info: How to Rotate a Scaled Plan Ka-6BR 281 4214 Help file 1 - International Model Airplane Coop link 192 2874 Help file 1 - link to Aerofred - plans,pdf etc 160 2397 Help file 1 - Link to colin usher mag.index 190 2837 Help file 1 - Link to Cover Art 294 4401 Help file 1 - Link to free PDF converter 198 2966 38 1 - Link to Gimp book (how to) 185 2764 Help file 1 - Link to Gimp Tutorials 185 2767 Help file 1 - Link to Gimpshop (feels like photoshp) 184 2755 1 - link to Globe Swift Plans CAD Earl Stahl 51 753 1 - link to golden age 157 2346 Help file 1 - link to irfanview 154 2308 1 - link to Keith Laumer Plans Dave Fritzke 111 1656 1 - Link to Kits and Plans Welli & Lancas 223 3334 1 - Link to PDF Converter 207 3097 1 - Link to Plans & 3-views 235 3523 1 - Link to Plans Avro Lancaster Aeromodeller 223 3331 Help file 1 - link to Plans French website 164 2447 1 - Link to Rcgroup control line plans 222 3321 1 - link to Republic P-47 31inch. -

Federal Aviation Administration Curriculum Guide For

U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Aviation Administration FAA Headquarters Aviation Education Division FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION CURRICULUM GUIDE FOR AVIATION MAGNET SCHOOLS PROGRAMS Prepared by Dr. Mervin K. Strickler, Jr. AHT-100-1-94 ABOUT THE AUTHOR Dr. Mervin K. Strickler, Jr., a native of Pennsylvania, graduated from Clarion State University. In 1951 he received his doctorate from Stanford University with specialization in aviation higher education. During his long and distinguished career he served as Director, USAF-Civil Air Patrol Aviation Education from 1951 to 1960, and as Director of the Federal Aviation Administration's Aviation Education Program from 1960 to 1979. From 1973 to 1979, he also worked with the Commonwealth of Independent States (then Soviet Union) as the FAA's representative for scientific and technical aviation education and training for all facets of civil aviation. He continues today as an international consultant on aviation education matters to industry, government, and all levels of education. Dr. Strickler's many publications and papers are included in libraries around the world. He is frequently called upon to speak at major aviation events and is well known nationally and internationally for his expertise in aviation education. PREFACE The Federal Aviation Administration's current interests, activities, projects and programs in aviation education represent and stem from a continuation and expansion of programs and similar initiatives of its predecessor organizations. Present programs are a result of the most recent FAA Administrator's Task Force Report on Aviation Education completed in 1990. The Report identified over fifty aviation education initiatives as appropriate to support the agency's objectives. -

Lectures on Applied Computational Fluid Dynamics

Lectures on Applied André Bakker 2008 © 2002-2006, 2008 - André Bakker - USA 1 Contents • Overview (3) • 1. Introduction to CFD (12) • 2. Flow fields (48) • 3. Conservation equations (98) • 4. Classification of flows (132) • 5. Solution methods (164) • 6. Boundary conditions (209) • 7. Meshing (240) • 8. Turbulence (275) • 9. Kolmogorov's theory (314) • 10. Turbulence models (357) • 11. Boundary layers and separation (399) • 12. Large eddy simulation (435) • 13. Heat transfer (475) • 14. Multiphase flows (516) • 15. Discrete phase modeling (539) • 16. Free surface flows (562) • Conservation equations overview (579) • Mathematics review (586) 2 Overview Welcome! • This document contains the lectures for the Computational Fluid Dynamics (ENGS 150) class that I taught at the Thayer School of Engineering at Dartmouth College from 2002-2006. • These lectures are provided – at no charge - for educational and training purposes only. • You are welcome to include parts of these lectures in your own lectures, courses, or trainings, provided that you include this reference: Bakker A. (2008) Lectures on Applied Computational Fluid Dynamics. www.bakker.org. 3 About the author • I received my Doctorate in Applied Physics from Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands in 1992. In addition, I obtained an MBA in Technology Management from the University of Phoenix. From 1991 to 1998 I worked at Chemineer Inc., a leading manufacturer of fluid mixing equipment. In 1998 I joined Fluent Inc., the leading developer of computational fluid dynamics software. Since 2006 I have been with ANSYS, Inc. • You can find me on the Web: – LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/andre-bakker-75384463 – ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Andre_Bakker – Personal web page: www.bakker.org André Bakker 4 Course materials • This class uses the book An introduction to Computational Fluid Dynamics: The Finite Volume Method by Versteeg and Malalasekera, Longman Scientific & Technical.