LAKE KANASATKA Water Quality Monitoring: 2011 Summary and Recommendations NH LAKES LAY MONITORING PROGRAM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Effects of Land Use on Water Quality in a Changing Landscape

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository NH Water Resources Research Center Scholarship NH Water Resources Research Center 6-1-2002 EFFECTS OF LAND USE ON WATER QUALITY IN A CHANGING LANDSCAPE Jeffrey Schloss University of New Hampshire, [email protected] William H. McDowell University of New Hampshire, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/nh_wrrc_scholarship Recommended Citation Schloss, Jeffrey and McDowell, William H., "EFFECTS OF LAND USE ON WATER QUALITY IN A CHANGING LANDSCAPE" (2002). NH Water Resources Research Center Scholarship. 85. https://scholars.unh.edu/nh_wrrc_scholarship/85 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the NH Water Resources Research Center at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in NH Water Resources Research Center Scholarship by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EFFECTS OF LAND USE ON WATER QUALITY IN A CHANGING LANDSCAPE Principal Investigators: Dr. Jeffrey Schloss, Dr. William McDowell, University of New Hampshire Descriptors: lake, stream, water quality, nutrients, land use Problem and Research Objectives: Objectives The continued collection and analysis of long-term water quality data in selected watersheds. The dissemination of the results of the analysis to cooperating agencies, water managers, educators and the public on a local, statewide and regional basis. To offer undergraduate and graduate students the opportunity to gain hands-on experience in water quality sampling, laboratory analysis, data management and interpretation. To further document the changing water quality in the College Brook Watershed in the face of land use changes and management efforts. -

Working for Clean and Healthy Lakes

NH LAKES 2019 ANNUAL REPORT Working for clean and healthy lakes ANNUAL REPORT 2019 Working for clean and healthy lakes 1 2019 ANNUAL REPORT NH LAKES 2019 Annual Report A reflection on the fiscal year ending March 31, 2019 You are NH LAKES! NH LAKES by Stuart Lord, Board Chair 17 Chenell Drive, Suite One Concord, NH 03301 603.226.0299 It has been an Everyone has a part to play! This nhlakes.org [email protected] extraordinary year for year, NH LAKES has flung the doors Board of Directors NH LAKES! Before wide open for anyone and everyone (as of March 31, 2019) you get deeper into to find their place in this rapidly- this report and read growing community of concerned Officers about all the citizens who value the beauty of New Stuart Lord (Silver Lake) programmatic Hampshire’s lakes. Chair John Edie (Meredith) accomplishments, In this report, you will see all the Vice Chair I want to try to make tangible for you different ways people of all ages have Bruce Freeman (Strafford) what is, on some levels, intangible. I’m responded to this call-to-action. We Treasurer referring to the evolution this John-Michael (JM) Girald (Rye) appreciate every pledge, contribution, Secretary organization has experienced as a story, photograph, and drawing shared Kim Godfrey (Holderness) result of the success of The Campaign for the purpose of keeping New At-Large for New Hampshire Lakes. Hampshire’s lakes clean and healthy. Board of Directors I’m talking about pride in the work we Inspired by the generosity of the 40 Reed D. -

2008 State Owned Real Property Report

STATE OF NEW HAMPSHIRE STATE OWNED REAL PROPERTY SUPPLEMENTAL FINANCIAL DATA to the COMPREHENSIVE ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT FOR THE YEAR ENDED JUNE 30, 2008 STATE OF NEW HAMPSHIRE STATE OWNED REAL PROPERTY SUPPLEMENTAL FINANCIAL DATA to the COMPREHENSIVE ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT FOR THE YEAR ENDED JUNE 30, 2008 Prepared by the Department of Administrative Services Linda M. Hodgdon Commissioner Division of Accounting Services: Stephen C. Smith, CPA Administrator Diana L. Smestad Kelly J. Brown STATE OWNED REAL PROPERTY TABLE OF CONTENTS Real Property Summary: Comparison of State Owned Real Property by County........................................ 1 Reconciliation of Real Property Report to the Financial Statements............................................................. 2 Real Property Summary: Acquisitions and Disposals by Major Class of Fixed Assets............................. 3 Real Property Summary: By Activity and County............................................................................................ 4 Real Property Summary: By Town...................................................................................................................... 13 Detail by Activity: 1200- Adjutant General......................................................................................................................................... 20 1400 - Administrative Services............................................................................................................................ 21 1800 - Department of Agriculture, -

Page Pond History and Guide

Page Pond and Forest A History and Guide Daniel Heyduk Acknowledgements Thanks are due to the people of Meredith, the Land and Community Heritage Investment Program (LCHIP), the Trust for Public Land, and the Meredith Conservation Commission for the acquisition of the Page Pond and Forest property. Thanks also to John and Nancy Sherman for the donation of a conservation easement on their land, which expands to over 600 acres the total conserved area accessible to the public. The Meredith Conservation Commission supported this project, reviewed drafts and gave guidance. John Moulton and John Sherman helped with information and suggestions. The Trust for Public Land shared maps. Richard Boisvert of the New Hampshire Division of Historical Resources contributed photos and described his excavation on Stonedam Island. Ralph Pisapia contributed photos. Paula Wanzer proofread the text. Peter Miller provided his research on Dudley Leavitt and the Page Brook sawmill. Vikki Fogg of the Meredith Town Assessing Department showed me historic tax records. Steve Taylor gave information on sheep. The Meredith Historical Society provided access to old maps. Rick Van de Poll identified natural communities. The Peabody Museum and Mount Kearsarge Indian Museum were very helpful. Dedication: to Harold Wyatt, who energetically researched Meredith history. Daniel Heyduk, Ph.D., resides in Meredith with his wife Beverly. An anthropologist and historian, he is a member of the Meredith Conservation Commission and a Forest Steward for the New England Forestry Foundation and the Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests. His The Hersey Mountain Forest: A Background History describes a conservation property in New Hampton and Sanbornton. -

Moultonborough Source Water Protection Plan, September 2016

Source Protection Plan for Moultonborough, New Hampshire September, 2016 Prepared By: Granite State Rural Water Association Andrew Madison, Source Water Specialist PO Box 596 Walpole, NH 03608 603-756-3670 [email protected] Produced For: Lakes Region Water Company, Lake Winnipesuakee Association, Town of Moultonborough. Acknowledgements Funding for this project was provided through a United States congressional appropriation to the National Rural Water Association and Granite State Rural Water Association and was administered in cooperation with the United States Department of Agriculture, Farm Service Agency. Additionally, this project was coordinated with the Lake Winnipesuakee Association’s Moultonborough Bay Inlet Water Quality Improvement Project. Cover Photo: Moultonborough and Lake Winnipesuakee from Mt. Whiteface in Sandwich, NH. Photo credit: Andrew Madison. Table of Contents 1. Introduction.................................................................................................................................1 1.1. Background and Purpose..............................................................................................1 1.2. Definitions....................................................................................................................1 2. Methods.......................................................................................................................................2 3. Town of Moultonborough...........................................................................................................3 -

NH Bird Records

New Hampshire Bird Records Fall 2014 Vol. 33, No. 3 his issue of New Hampshire Bird Records with its color cover is sponsored by an Tanonymous donor. Thank you! NEW HAMPSHIRE BIRD RECORDS In This Issue VOLUME 33, NUMBER 3 FALL 2014 From the Editor ........................................................................................................................1 Photo Quiz ...............................................................................................................................1 MANAGING EDITOR Fall Season: August 1 through November 30, 2014 ...................................................................2 Rebecca Suomala by Lauren Kras and Ben Griffith 603-224-9909 X309, [email protected] Concord Nighthawk Migration Study – 2014 Update .............................................................25 by Rob Woodward TEXT EDITOR Field Trip Report – Concord Sparrow Field Trip ......................................................................25 Dan Hubbard by Rob Woodward SEASON EDITORS Fall 2014 New Hampshire Raptor Migration Report ..............................................................26 Eric Masterson, Spring by Iain MacLeod Tony Vazzano, Summer The Life and Death of a Roseate Tern ......................................................................................30 Lauren Kras/Ben Griffith, Fall by Stephen R. Mirick Pamela Hunt, Winter Backyard Birder – What is That Strange Bird? Leucism in Birds ..............................................31 LAYOUT by Aiden Moser Kathy McBride Field -

Historical and Cultural Resources Chapter

VI. Historical and Cultural Resources Preface With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020, it became clear that more than just a customary update of the prior Historical & Cultural Resources chapter to the town Master Plan was in order. The opportunity to review a decade of planning efforts and historic preservation activity indicates that Moultonborough is at a tipping point, with the future of a significant community landmark in the balance. Will the Town support the rehabilitation and redevelopment of the historic Taylor House to aid in the economic revitalization of Moultonborough Village, and in doing so follow the recommendations of every Planning study and report from the past decade? Or will the Town demolish this character-defining building at the Village center, creating a void that represents a failure of Planning and vision? A town’s Master Plan forms the basis for ordinances that help to manage growth, development, and change, which in turn are designed to preserve and enhance the unique quality of life and culture of New Hampshire, in accordance with the principles of smart growth, sound planning, and wise resource protection (RSA 674:2, I). As per RSA 674:2, III (h), this chapter “identifies cultural, archaeological, and historic resources and protects them for rehabilitation or preservation from the impact of other land use tools such as land use regulations, housing, or transportation.” In the field of historic preservation, historical and cultural resources (districts, sites, buildings, structures, objects, and landscapes) are defined as over 50 years in age. Historic preservation is inseparable from sound planning. -

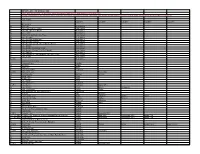

2020 PRELIMINARY VALUES TOWN of MOULTONBOROUGH REPORT by OWNER's NAME Total Assessed Total Assessed Total Assessed Owner Parcel ID Location Land Improvements Value

2020 PRELIMINARY VALUES TOWN OF MOULTONBOROUGH REPORT BY OWNER'S NAME Total Assessed Total Assessed Total Assessed Owner Parcel ID Location Land Improvements Value 1 FIELDSTONE WAY REALTY TRUST 000024 / 004 / 001 / 000 / 000 FIELDSTONE WAY 135,500 0 135,500 10 SECOND POINT REALTY TRUST 000133 / 039 / 000 / 000 / 000 10 SECOND POINT ROAD 630,300 589,800 1,220,100 100 SERIES SEWER SYS ASSOC 000174 / 075 / 000 / 000 / 000 KRAINEWOOD DRIVE 0 0 0 103 EVANS ROAD NOMINEE TRUST 000005 / 008 / 000 / 000 / 000 EVANS ROAD 62,300 0 62,300 103 EVANS ROAD NOMINEE TRUST 000005 / 007 / 000 / 000 / 000 103 EVANS ROAD 83,500 169,400 252,900 1040 WHITTIER LLC 000043 / 018 / 000 / 000 / 000 WHITTIER HIGHWAY 44,900 0 44,900 1040 WHITTIER LLC 000043 / 019 / 000 / 000 / 000 1040 WHITTIER HIGHWAY 97,800 407,200 505,000 111 KIMBALL DRIVE PROPERTY TRUST 000223 / 075 / 001 / 000 / 000 KIMBALL DRIVE 89,800 0 89,800 111 KIMBALL DRIVE PROPERTY TRUST 000223 / 045 / 000 / 000 / 000 111 KIMBALL DRIVE 616,500 391,600 1,008,100 113 EVANS ROAD REV TRUST 000005 / 009 / 000 / 000 / 000 113 EVANS ROAD 61,500 10,900 72,400 12 GANSY ISLAND MOULTONBOROUGH LLC 000130 / 067 / 000 / 000 / 000 12 GANSY ISLAND 177,900 239,200 417,100 123 KIMBALL DRIVE TRUST 000223 / 047 / 000 / 000 / 000 123 KIMBALL DRIVE 492,500 169,800 662,300 1241 WHITTIER HIGHWAY LLC 000018 / 017 / 000 / 000 / 000 1241 WHITTIER HIGHWAY 99,600 240,900 340,500 126 FAR ECHO ROAD REALTY TRUST 000245 / 020 / 000 / 000 / 000 126 FAR ECHO ROAD 158,900 99,100 258,000 128 LEE ROAD LLC 000068 / 001 / 000 / 000 / 000 LEE -

Water Resources Research Center Annual Technical Report FY 2002

Water Resources Research Center Annual Technical Report FY 2002 Introduction Research Program Linking Lakes with the Landscape: The Fate of Terrestrial Organic Matter in Planktonic Food Webs Basic Information Linking Lakes with the Landscape: The Fate of Terrestrial Organic Matter in Title: Planktonic Food Webs Project Number: 2002NH1B Start Date: 3/1/2002 End Date: 2/28/2003 Funding Source: 104B Congressional District: Research Category: None Focus Category: Ecology, Models, Surface Water Descriptors: None Principal Kathryn L. Cottingham, Jay Terrence Lennon Investigators: Publication 1. Lennon, J.T. Terrestrial carbon input drives CO2 output from lake ecosystems. In review, Oecologia. 2. Lennon, J.T. Sources of terrestrial-derived subsidies affects aquatic bacterial metabolism. In preparation for submission to Microbial Ecology. WRRC FY 2002 Annual Progress Report LINKING LAKES WITH THE LANDSCAPE: THE FATE OF TERRESTRIAL ORGANIC MATTER IN PLANKTONIC FOOD WEBS Jay T. Lennon and Kathryn L. Cottingham Department of Biological Sciences, Dartmouth College 6044 Gilman Laboratory, Hanover, NH 03755 Phone: (603) 646-0591 Fax: (603) 646-1347 [email protected] or [email protected] PROBLEMS AND OBJECTIVES We are evaluating how terrestrially-derived dissolved organic matter (DOM) influences the functioning of lake ecosystems. Terrestrially-derived DOM is commonly the largest carbon pool in lakes. As such, terrestrial DOM represents a major source of potential energy for aquatic food webs that may subsidize higher trophic levels (including zooplankton and fish) and determine whether lake ecosystems act as sources or sinks of CO2. Our project addresses three main factors that influence terrestrial carbon flow in lakes. Objective 1: Determine whether the energetic importance of terrestrial DOM in lakes is ultimately determined by bacterial metabolism. -

Lake Level Management a Balancing Act Nh Lakes

LAKE LEVEL MANAGEMENT A BALANCING ACT NH LAKES June 16, 2021 James W. Gallagher, Jr., P.E Chief Engineer Dam Bureau 271-1961 [email protected] State Dams Hazard Classification AGENCY TOTALS HIGH SIG. LOW NM DES 40 25 40 6 111 NHFG 4 6 43 47 100 DNCR 2 3 9 17 31 DOT 1 4 4 18 27 UNH 1 1 0 3 5 Glencliff 0 0 0 2 2 Veterans Home 0 0 0 2 2 TOTAL 48 39 96 95 278 Recreational Resources Ossipee Lake Squam Lake Newfound Lake Lake Winnipesaukee Winnisquam Lake Lake Sunapeee Emergency Action Plans Inundation Mapping Population At Risk Downstream of State Owned High and Significant Hazard Dams More than 4,000 houses More than 130 State Road Crossings More than 800 Town Road Crossings Dam Operations Emergency Operations Remote Dam Operations DEPTH (in feet) LAKE RIVER TOWN START DATE FROM FULL Angle Pond Bartlett Brook Sandown Oct. 13 2’ Akers Pond Greenough Brook Errol Oct. 13 1’ Ayers Lake Tributary to Isinglass River Barrington Oct. 20 3’ Ballard Pond Taylor Brook Derry Oct. 13 2’ Barnstead Parade Suncook River Barnstead Oct. 13 1.5’ Bow Lake Isinglass River Strafford Oct. 13 4’ Buck Street Suncook River East Pembroke Oct. 13 6’ Bunker Pond Lamprey River Epping Oct. 13 2’ Burns Lake Tributary to Johns River Whitefield Oct. 13 1.5’ Chesham Pond Minnewawa Brook Harrisville Oct. 13 2’ Crystal Lake Crystal Lake Brook Enfield Oct. 13 4’ Crystal Lake Suncook River Gilmanton Oct. 13 3’ Deering Reservoir1 Piscataquog River Deering Oct. -

Lakes Region

Aú Aè ?« Aà Kq ?¨ Aè Aª Ij Cã !"b$ V# ?¨ ?{ V# ?¬ V# Aà ?¬ V# # VV# V# V# Kq Aà A© V# V# Aê !"a$ V# V# V# V# V# V# V# ?¨ V# Kq V# V# V# Aà C° V# V# V# V#V# ?¬A B C D V# E F G 9.6 V#Mount Passaconaway Kq BAKERAê RIVER 10.0 Saco River WARRENWARREN 9.2 Mount Paugus Mount Chocorua 0.9 NH 25A 0.2 Peaked Hill Pond Ij Mad River Mount Whiteface V# ?Ã Noon0 Peak 2.5 5 10 V# Pequawket Pond CONWAY Mud Pond V# CONWAY ELLSWORTHELLSWORTH Aj JenningsV# Peak ?¨Iona Lake Cone Pond MilesALBANYALBANY Conway Lake LAKES REGIONNH 175 THORNTONTHORNTON WHITE MOUNTAIN NATIONAL FOREST Ellsworth Pond WATERVILLEWATERVILLEV# VALLEYVALLEY Upper Pequawket Pond Flat Mountain Ponds Snake Pond WENTWORTHWENTWORTH US 3 Sandwich MountainSandwich Dome Ledge Pond WW H H I I T T E E MM O O U U N N T T A A I I N N RR E E G G I I O O N N Whitton Pond BICYCLE ROUTES V# Haunted Pond Dollof Pond 1 I NH 49 Middle Pea Porridge Pond 1 27 Pea Porridge Pond Ae ")29 13.4 Labrador Pond 4.0 ?{ 34 Atwood Pond Aá 8.6 Campton Pond Black Mtn Pond Lonely Lake Davis Pond Tilton Pond Câ James Pond 14.1 Chinook Trail South Branch Moosilauke Rd 13.0 2.1 Chase Rd Chocorua Lake RUMNEYRUMNEY 2.8 ")28 Great Hill Pond fg Tyler Bog Roberts Pond 2.0 Guinea Pond Little Lake Blue PondMADISONMADISON R-5 4.2 HEMMENWAY STATE FOREST Mack Pond Loud Pond NH 118 Pemigewasset River 5.1 Mailly Pond Drew Pond 3.7 fg Buffalo Rd CAMPTON Hatch PondEATONEATON 5.3 CAMPTON Baker River Silver Pond Beebe River ?¬ Quincy Rd Chocorua Rd DORCHESTERDORCHESTER 27 0.8 Durgin Pond ") SANDWICHSANDWICH 4.5 Loon Lake BLAIR STATE -

IMPORTANT INFORMATION: Lakes with an Asterisk * Do Not Have Depth Information and Appear with Improvised Contour Lines County Information Is for Reference Only

IMPORTANT INFORMATION: Lakes with an asterisk * do not have depth information and appear with improvised contour lines County information is for reference only. Your lake will not be split up by county. The whole lake will be shown unless specified next to name eg (Northern Section) (Near Follette) etc. LAKE NAME COUNTY COUNTY COUNTY COUNTY COUNTY Great Lakes GL Lake Erie Great Lakes GL Lake Erie (Port of Toledo) Great Lakes GL Lake Erie (Western Basin) Great Lakes GL Lake Huron Great Lakes GL Lake Huron (w West Lake Erie) Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan (Northeast) Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan (South) Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan (w Lake Erie and Lake Huron) Great Lakes GL Lake Ontario Great Lakes GL Lake Ontario (Rochester Area) Great Lakes GL Lake Ontario (Stoney Pt to Wolf Island) Great Lakes GL Lake Superior Great Lakes GL Lake Superior (w Lake Michigan and Lake Huron) Great Lakes GL Lake St Clair Great Lakes GL (MI) Great Lakes Cedar Creek Reservoir AL Deerwood Lake Franklin AL Dog River Shelby AL Gantt Lake Mobile AL Goat Rock Lake * Covington AL (GA) Guntersville Lake Lee Harris (GA) AL Highland Lake * Marshall Jackson AL Inland Lake * Blount AL Jordan Lake Blount AL Lake Gantt * Elmore AL Lake Jackson * Covington AL (FL) Lake Martin Covington Walton (FL) AL Lake Mitchell Coosa Elmore Tallapoosa AL Lake Tuscaloosa Chilton Coosa AL Lake Wedowee (RL Harris Reservoir) Tuscaloosa AL Lay Lake Clay Randolph AL Lewis Smith Lake * Shelby Talladega Chilton Coosa AL Logan Martin Lake Cullman Walker Winston AL Mobile Bay Saint Clair Talladega AL Ono Island Baldwin Mobile AL Open Pond * Baldwin AL Orange Beach East Covington AL Bon Secour River and Oyster Bay Baldwin AL Perdido Bay Baldwin AL (FL) Pickwick Lake Baldwin Escambia (FL) AL (TN) (MS) Pickwick Lake (Northern Section, Pickwick Dam to Waterloo) Colbert Lauderdale Tishomingo (MS) Hardin (TN) AL (TN) (MS) Shelby Lakes Colbert Lauderdale Tishomingo (MS) Hardin (TN) AL Tallapoosa River at Fort Toulouse * Baldwin AL Walter F.