M.Mcbride Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

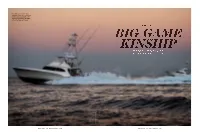

MAY 2019 6 4 MARLINMAG.COM Most Multi-Generational Family

Most multi-generational family fishing operations are a result of the desire to spend quality time with one another hunting for big game, both on the water and on land. BY JASON PIM BIG-GAME KINSHIP THREE FAMILIES SHAPE THEIR FISHING LEGACIES JESSICA HAYDAHL RICHARDSON JESSICA HAYDAHL MAY 2019 64 MARLINMAG.COM MAY 2019 65 MARLINMAG.COM MAR0519_F-FAM_Top Families in Fishing.indd 64 2/13/19 12:09 PM MAR0519_F-FAM_Top Families in Fishing.indd 65 2/13/19 12:09 PM Even these most accomplished families started out humbly. “My dad, Jack Huddle, was from West Virginia and had never fished in the ocean until he went to The Citadel in Charleston, South Carolina,” Harris Huddle explains. Like many of us, patriarchs such as Jack were introduced to the sport of fishing from shore. As time progressed, they simply found themselves wanting more and worked hard to achieve it. Gray Ingram, owner of the 63-foot Scarborough, Big Oh, happened across his first billfish by chance too. “When I was about 35, a neighbor and I were mahi fishing, and we accidentally caught a blue marlin," Ingram recalls. "I’ve been hooked ever since.” As these men worked their way up the food chain of life, busi- ness, boat ownership and fishing pursuits, they brought their families along for the ride. The result are three teams who, no matter the tournament, are competitors to be reckoned with. THE RICHARDSONS Whoo Dat, Jarrett Bay 58 Grand Isle, Louisiana One common thread between these families is a voracious appetite for travel in the pursuit of marlin and big-game fish. -

Teacher's Notes

PENGUIN READERS Teacher’s notes LEVEL 5 Teacher Support Programme The Citadel A J Cronin Chapter 2: Manson is shocked to hear from Denny, another junior doctor, that bad water in the town kills many people through typhoid, and that the senior doctors, apart from Page, are incompetent or only interested in money. Chapter 3: By drinking only boiled water, some typhoid patients get better, but typhoid is spreading. Denny proposes to blow up the old sewer in order to oblige the authorities to build a new safe one. Andrew helps and the plan works. Chapter 4: Andrew has an argument with the schoolteacher about keeping a contagious child at home. About the author Chapter 5: Andrew falls in love with the schoolteacher, Christine Barlow. Archibald Joseph Cronin was born on 19th July 1896 in Cardross near Glasgow on the west coast of Scotland. Chapter 6: A man who had become violent is cured by His mother had defied her Scottish, Protestant family by Manson’s hormone treatment, while other doctors had marrying an Irishman and becoming a Catholic. Cronin simply wanted to send him to a mental hospital. was very bright and won many prizes at Cardross Village Chapter 7: Andrew and Christine go to a doctors’ School and the Dumbarton Academy, but this did not conference. An old friend, Freddie Hamson explains to endear him to his fellow pupils, and he was a shy and him how to make much more money by only treating rich lonely boy. patients. Cronin graduated with honours from medical school Chapter 8: Andrew managed to help a difficult birth and at the end of the First World War in 1919. -

Cronin Ing:Maquetación 3.Qxd

Alberto Enrique D’Ottavio Cattani J Med Mov 5 (2009): 59-65 JMM Archibald Joseph Cronin: a Writing-Doctor Between Literature and Film Alberto Enrique D’Ottavio Cattani1,2 1Cátedra de Histología y Embriología. Facultad de Ciencias Médicas. 2Consejo de Investigaciones de la Universidad Nacional de Rosario (Argentina). Correspondence: Alberto Enrique D’Ottavio Cattani, Matheu 371. 2000 Rosario, Santa Fe (Argentina). e-mail: [email protected] Received 1 October 2008; modified 18 March 2009; accepted 19 March 2009 Summary This paper broaches the subject of the life and numerous cinematographic and TV adaptations of the vast and controversial liter- ary work of Scottish doctor Archibald Joseph Cronin (1896-1981). Through it, we intend to stress the influence his books and/or the films based on them had on many young generations who, under their shelter, chose a career in medicine. Prize-winning writer and PhD, in his works -formally adorned with his great talent for description and observation- he intermingles naturalism, conflicting passions, medical situations and social criticism. Beyond all discussion about his literary career and his repercussion on film, his influence on those who embraced Medicine following in the steps of his characters, many of whom were nothing more than a reflection of himself, is unquestionable. Keywords: Cronin, Doctor, Writer, Film, Literature. To AJ Cronin, whose works strengthened my decision to become a doctor 19 July, 1896. An only child, his mother was Jessie Montgomerie and his father Patrick Cronin. In an Life and work of Archibald Joseph Cronin apparently paradoxical way, following the death of his father, who professed Catholicism, Archibald was The writer-doctors whose works have been raised as a Catholic by his Protestant mother. -

Sleepy Times

DEPARTMENT OF ANESTHESIA AND PERIOPERATIVE MEDICINE SLEEPY TIMES VOLUME 12, ISSUE 7 JULY 2018 Message from the Chairman: SHARE, LAUGH, LOVE, REPEAT -Scott T. Reeves, MD, MBA This month, I want to start the July edition of Sleepy Times with my Inside This Issue: resident and fellow graduation address. “Dear residents and fellows, faculty, family and friends, -Message from Chairman 1-2 -Graduation Celebration 3-6 I want to welcome all of you to the 2018 graduation ceremony. This year, we will celebrate the graduation of 13 residents, three critical care, one -Wake Up Safe 7-10 regional anesthesiology, and two adult cardiothoracic fellows. Can our -New Faculty Members 11-12 graduates please stand, as they deserve a special round of applause? Now I would like their family (spouses, children and parents) to stand. They too deserve a -Dept. Hurricane Plan 12 round of applause. -Retirement Luncheon 13 During last year’s graduation, my address to you was short due to my father’s -New Staff and Babies 14 unexpected death. You may not know this, but he passed away last June, secondary to a -Resident Welcome Party 15-17 traumatic lawn mower accident resulting in a head injury from which he did not recover. It has been a rough year, but one with a lot of self-reflection. Fortunately, I had a very -Charleston in USA Today 18 Best Places Artlice good relationship with my father, and we frequently built memories together and with -Coffee Talk with 18 my children. I would like to dedicate these remarks in his honor and title this address: Dr. -

Fifty Years of Thoracic Surgery*

FIFTY YEARS OF THORACIC SURGERY* JOHN ALEXANDER, M.D. Professor of Surgery, University of Michigan Medical School ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN NESTHESIA, asepsis and antisepsis American, wrote of “the extreme inherent gave the surgery of fifty years ago a diffrcuIties and dangers which must be met A firm foundation upon which to in our attempts to invade the thorax,” and build. Thoracic surgery, of course, shared Taeufert, a German, asserted that surgeons in the stimuIus these three great discover- were we11 aware that most operations in the ies gave to experimenta and cIinica1 sur- chest, perhaps with the exception of empy- gery but the advance of thoracic surgery ema operations, will give onIy Iimited was necessariIy heId in abeyance unti1 resuIts, whiIe Stephen Paget, an EngIish- roentgenoIogy was discovered in 1893 and, man, introduced a book, “The Surgery of to a Iess extent, unti1 bronchoscopy, esoph- the Chest,” which he pubIished in 1896, by agoscopy, thoracoscopy, bronchography saying that the time was ripe for the and respiration under differentia1 pressure presentation of the vaIuabIe facts he had were stiI1 Iater made avaiIabIe. coIIected “because there are signs that we These tooIs are now used aImost daiIy in have reached a stage in this portion of our every active thoracic surgery cIinic and are art beyond which, on our present Iines, we rightIy considered as indispensabIe. WhiIe cannot advance much further.” Manning reading many case histories of fifty years wrote in 1894, “The Iungs were among the ago, I was constantIy aware of the over- Iast [interna organs] to receive systematic wheIming difficuIties the clinicians of that treatment by operations” and he added time faced in attempting to determine the that such operations were few, having nature, size and exact position of intra- foIIowed experiments on animaIs or having thoracic Iesions without the use of roent- been undertaken as a Iast resort in incur- genology and bronchoscopy; and it is not abIe cases. -

Senior Activities

City of Charleston Mayor’s Office on Aging Enjoying Aging in Charleston Picture available at sailmagazine.com Information in this article is subject to change at any time! Please check with the business or organization prior to visiting for the most up-to-date information! Janet M. Schumacher, Coordinator, Mayor’s Office on Aging 50 Broad Street Charleston, SC 29401 Phone: (843)-577-1389 Fax: (843)-724-3706 Email: [email protected] 1 Table of Contents City of Charleston Recreation……………………………………………………………pg. 4 Aquatics and Water recreation programs…..……………………..pg. 4-5 Tennis…………………………………………………………………………………………….pg. 5 Sporting Events…………………………………………………………………………..pg. 5 West Ashley- City recreation programs………………. ……………pg. 5-6 James Island- City recreation programs……………………………..pg. 6-7 Area Recreation……………………………………………………………………………………..pg. 7-11 Bowling………….…………………………………………………………………………....pg. 7 Charles Towne Landing- State Park…………………………………...pg. 7-8 Charleston County Parks………………………………………………………..pg. 8 The Charleston Singles Ballroom Dance Group……………….pg. 8-9 Golf Courses……………………………………………………………………………….pg. 9-10 Hunting and Fishing…………………………………………………………………pg. 10 Lowcountry Senior Center……………………………………………………..pg. 10 Miniature Golf……………………………………………………………………………pg. 11 Park Angels- Charleston Parks Conservancy……………………pg. 11 South Carolina State Parks- Palmetto Pass……………………….pg. 11 Sporting Events……………………………………………………………………………………..pg. 12 River Dogs Baseball…………………………………………………………………..pg. 12 Stingrays Hockey……………………………………………………………………….pg. 12 Educational -

Moral Corruption in A.J.Cronin's the Citadel a Socio-Psychological Method

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN (Online): 2319-7064 Index Copernicus Value (2016): 79.57 | Impact Factor (2017): 7.296 Moral Corruption in A.J.Cronin‟s the Citadel a Socio-Psychological Method Luboya Numbi Buta Oscar Assistant à l‟Institut Supérieur of Commerce de Lubumbashi Abstract: The major concern of this paper about Moral Corruption in A.J.CRONIN’S The Citadel is to show how cupidity pushes people to conceive evil reasoning and very tricky evil schemes so as to get money or other favors forgetting the needs of the entire community. Throughout this paper, we intend then to transform the behavior of our contemporaries, among them we mention physicians and politicians. Briefly speaking, our contribution to this dissertation is to inform leaders that if they want to promote good moral values, they have to avoid corruption, misunderstanding of the ruled class, and they have to apply justice. It should be stressed from the beginning that the story turns around a young Doctor that we consider as the main character. His name is Andrew Manson. His story according to Cronin is situated around few years before World War II. He completed his studies in England where corruption is the only way of survival, above all in the medical field. MANSON gets really, shocked face to this bad situation which prevailed in the English medical world. That moral corruption is brought about and made possible by a bad medical organization system in England some few years before the global World War II. He tries to fight against it; but in the end he retraced his step, became himself the victim of this corruption. -

PATRICIA A. RICKICKI and PATRICIA A

STATE OF NEW YORK SUPREME COURT : COUNTY OF CATTARAUGUS ___________________________________________________ PATRICIA A. RICKICKI and PATRICIA A. RICKICKI as Executrix of the ESTATE OF DAVID P. RICKICKI, Index No. 53395 vs. Plaintiffs, BORDEN CHEMICAL, DIVISION OF BORDEN, INC., et al., Defendants. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------- MICHAEL C. CROWLEY and SHARON M. CROWLEY, Index No. 61024 vs. Plaintiffs, C-E MINERALS, INC., et al. Defendants. ____________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ DEFENDANTS’ MEMORANDUM OF LAW IN SUPPORT OF MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT ______________________________________________________________________________ PRELIMINARY STATEMENT The issue before this Court remains whether remote silica sand suppliers have a duty to warn industrial customers that prolonged inhalational overexposure to silica can cause a lung disease, silicosis, which has been a matter of common knowledge in the industrial, labor, medical, and governmental communities since at least the middle of the last century, and which has been the basis of extensive regulations, by both the New York and federal governments, designed to protect industrial workers where silica sand is used. This issue was previously presented to this Court, which held that the remote silica suppliers had no duty to warn on all the facts and circumstances of these cases, and that any claimed breach of duty was not a proximate cause of the claimed injuries. Plaintiffs’ appealed from this Court’s decision order and the appeal came to be heard by the Appellate Division Fourth Department. By Memorandum and Order dated March 20, 2009, the Appellate Division Fourth Department modified in part the decision of this Court by reinstating the negligence and products liability causes of action insofar as those causes of action are based on a failure to warn. -

BJGP Library: the Citadel

Out of Hours bJGp library: The Citadel A pOtent reminder Of life befOre Address fOr COrrespOndenCe tHe nHs “It is said that the novel’s Graham Watt THE CITADEL General Practice & Primary Care, AJ Cronin effect on public opinion, 1 Horselethill Road, Glasgow G12 9LX, UK. Panmacmillan, 2013, PB, 432pp, £16.99 e-mail: [email protected] 978-1447244554 when it was published in 1937, paved the way for strength of doctors working together within Bevan’s NHS.” an organised system. The sensation of the novel, however, came from its description of the medical profession at that time, as Manson with sensational the novel was at the time, MD and MRCP, moves to Harley Street scandalising the medical profession and and private practice, socialises with the alarming the public, with a narrative rich and famous, loses his moral compass, showing that, while the interests of patients commits adultery, and becomes rich, and doctors usually overlapped, they did not selling bogus treatments to the worried always coincide. well. After he assists at a botched operation Cronin worked as a doctor for 11 years, and accuses the surgeon of murder, the before a 6-month period of convalescence profession closes ranks, charging Manson from duodenal ulcer (now curable with a with unprofessional conduct, as a result of The BJGP Library is a new regular column in short course of antibiotics) allowed him his having referred a tuberculous patient to the Out of Hours section where contributors to write his first novel. He never practised a medically-unqualified pioneer of induced write a 600-word article relating to a single medicine again, but mined his clinical pneumothorax. -

Rev. 09/2016 International Baccalaureate Credit

International Baccalaureate Credit The International Baccalaureate (IB) Program is accepted by The Citadel, The Military College of South Carolina. Students who have achieved a minimum score of '4' on a Higher Level (HL) IB examination will be awarded credit as detailed in the chart below. Credit is not awarded for Standard Level (SL) or Extended Essay (EE) work. Minimum Credit International Baccalaureate Exam Citadel Credit Score Hours 4 GNRL 101, 102 6 Albanian A: Literature HL 5 GNRL 101, 102, 103 9 4 GNRL 101, 102 6 Amharic A: Literature HL 5 GNRL 101, 102, 103 9 4 GNRL 101, 102 6 Arabic A: Language & Literature HL 5 GNRL 101, 102, 103 9 4 GNRL 101, 102 6 Arabic A: Literature HL 5 GNRL 101, 102, 103 9 4 GNRL 101, 102 6 Arabic B HL 5 GNRL 101, 102, 103 9 4 GNRL 101, 102 6 Azerbaijani A: Literature HL 5 GNRL 101, 102, 103 9 4 GNRL 101, 102 6 Belarusian A: Literature HL 5 GNRL 101, 102, 103 9 4 GNRL 101, 102 6 Bengali A: Literature HL 5 GNRL 101, 102, 103 9 4 BIOL 101, 111 or BIOL 130, 131* 4 Biology HL 6 BIOL 101, 111, 102, 112 or BIOL 130, 131, 140, 141* 8 4 GNRL 101, 102 6 Bosnian A: Literature HL 5 GNRL 101, 102, 103 9 4 GNRL 101, 102 6 Bulgarian A: Literature HL 5 GNRL 101, 102, 103 9 4 GNRL 101, 102 6 Burmese A:Literature HL 5 GNRL 101, 102, 103 9 Rev. 09/2016 Minimum Credit International Baccalaureate Exam Citadel Credit Score Hours Business & Management HL 4 BADM 338 3 4 GNRL 101, 102 6 Catalan A: Literature HL 5 GNRL 101, 102, 103 9 Chinese A: Language & Literature HL 4 CHIN 101, 102, 201, 202, 301 15 Chinese A: Literature HL -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} the Citadel by AJ Cronin

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} The Citadel by A.J. Cronin The Citadel PDF Book by A.J. Cronin (1937) Download or Read Online. The Citadel PDF book by A.J. Cronin Read Online or Free Download in ePUB, PDF or MOBI eBooks. Published in 1937 the book become immediate popular and critical acclaim in classics, historical books. The main characters of The Citadel novel are Andrew Manson, Dr Philip Denny. The book has been awarded with National Book Award for Fiction (1937), Edgar Awards and many others. One of the Best Works of A.J. Cronin. published in multiple languages including English, consists of 368 pages and is available in Paperback format for offline reading. The Citadel PDF Details. Author: A.J. Cronin Book Format: Paperback Original Title: The Citadel Number Of Pages: 368 pages First Published in: 1937 Latest Edition: November 30th 1983 Language: English Awards: National Book Award for Fiction (1937) Generes: Classics, Historical, Historical Fiction, Novels, European Literature, British Literature, Main Characters: Andrew Manson, Dr Philip Denny, Christine Barlow (Manson), Dr Hope Formats: audible mp3, ePUB(Android), kindle, and audiobook. The book can be easily translated to readable Russian, English, Hindi, Spanish, Chinese, Bengali, Malaysian, French, Portuguese, Indonesian, German, Arabic, Japanese and many others. Please note that the characters, names or techniques listed in The Citadel is a work of fiction and is meant for entertainment purposes only, except for biography and other cases. we do not intend to hurt the sentiments of any community, individual, sect or religion. DMCA and Copyright : Dear all, most of the website is community built, users are uploading hundred of books everyday, which makes really hard for us to identify copyrighted material, please contact us if you want any material removed. -

Read Book the Vintage Book of Modern Indian Literature 1St Edition

THE VINTAGE BOOK OF MODERN INDIAN LITERATURE 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Amit Chaudhuri | 9780375713002 | | | | | The Vintage Book of Modern Indian Literature 1st edition PDF Book Buying Format see all. You May Also Like. This novel won the Man Booker Prize and achieved a remarkable combination of global popularity and critical acclaim. Topic see all. AbeBooks has compiled a list of the most collectible books published between and The thirty-eight authors collected by novelist Amit Chaudhuri write not only in English but also in Hindi, Bengali, and Urdu. Books by Amit Chaudhuri. Best Offer. Guaranteed Delivery see all. No Preference. Want to Read saving…. Guaranteed 3 day delivery. Basic Writings of St. About First Edition Books If the initial print run - known as the 'first printing' or 'first impression'- sells out and the publisher decides to produce a subsequent printing with the same typeset, books from that second print run can be described as a first edition, second printing. Fine Binding. It won the National Book Award for Fiction. Nora Roberts. Science Fiction. Trivia About The Vintage Book List View. Published Date: min to max. You May Also Like. Type see all. From a Buick 8 Stephen King This novel was published in So like the Granta book apparently, only more and better! The Vintage Book of Modern Indian Literature 1st edition Writer Special Attributes see all. Carl Hiaasen found a copy and his publisher Alfred A. Got one to sell? There are many guides to identifying first edition books, including AbeBooks' own , but there is sometimes no definitive answer.