APPENDIX E REPLACEMENT Cultural

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IEDC Data Standards for San Bernardino County

TABLE 1 SAN BERNARDINO COUNTY DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS Population Five Year Projection 2000 2008 2009 2013 Population by Age Group Under - 17 551,976 605,352 609,972 650,474 18 - 34 418,811 555,767 552,116 606,492 35 - 54 476,248 559,899 552,040 618,066 55 - 74 192,482 266,520 275,549 349,543 75 - Older 65,300 76,443 78,243 90,279 % Distribution by Age Group Under - 17 32.29% 29.30% 29.50% 28.10% 18 - 34 24.50% 26.90% 26.70% 26.20% 35 - 54 27.86% 27.10% 29.69% 26.70% 55 - 74 11.26% 12.90% 13.33% 15.10% 75 - Older 3.82% 3.70% 3.76% 3.90% Median Age 30.4 30.8 30.98 32.2 Percent Change 1990-2000 20.50% Percent Change 2000-2008 20.90% Percent Change 1990-2008 45.70% Percent Change 2008-2013 12.00% Households Number 464,737 620,777 617,191 677,480 Median Household Income 42,881 53,036 56,079 60,218 Household Income Distribution Under - $35,000 142,096 202,994 191,038 212,554 $35,001 - $50,000 68,920 98,457 88,026 105,302 $50,001 - $75,000 113,856 162,651 121,455 176,125 $75,001 - Above 140,792 201,131 216,672 232,172 Workforce Education Attainment (25 - 64 Years of Age) Percentage % Under - 12 Years 10.27 12 - 15 Years 15.23 12 Years Only 25.11 Some College 25.95 Associate Degrees 7.6 Subtotal 84.16 College Graduates 15.82 16 Years - More 5.45 16 Years Only 10.37 Total 15.82 TABLE 2 SAN BERNARDINO COUNTY LABOR FORCE CHARACTERISTICS Civilian Labor Force 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 Unemployment Rate (for month & year use most 5.20% 4.80% 6.00% 8.00% 13.90% recent information available and seasonally adjusted annual average) Non-Agricultural Employment -

Cucamonga Creek and Tributaries, San Bernardino and Riverside Counties, California

STATEMENT OF FINDINGS CUCAMONGA CREEK AND TRIBUTARIES SAN BERNARDINO AND RIVERSIDE COUNTIES CALIFORNIA 1. ' As District Engineer, Los Angeles District, U. S. Army Corps of Engineers, I have reviewed and evaluated, in what I believe to be the public interest, the project Tor Cucamonga Creek, West Cucamonga Creek, and Deer Creek channel improvements, from the Sari Gabriel Mountains to Prado Reservoir, San Bernardino and Riverside Counties, California, which is outlined in the project description section of this environmental statement. In evaluating this project, I have considered all project documents, comments by concerned agencies and individuals, and possible alternatives. 2. My staff has (a) compiled an environmental statement that covers the fundamental and basic environmental impacts; (b) computed the cost and economic impacts of the proposed project; (c) considered the project effects on the surrounding community; (d) considered alternatives; and (e) prepared engineering plans for the project. I have reviewed their findings and the comments of Federal, State, local agencies, and interested parties. \ 3. In my evaluation the following points were considered: a. ' Economic considerations. The proposed project will provide flood damage reduction for floods up to standard-project-fiood magnitude to developed areas consisting of valuable residential, commercial, agricultural, and industrial property, important -r-utilities, arterial and interstate highways, an international airport, and transcontinental railroad lines serving the area. b. ‘ Engineering considerations. The project is designed to provide flood protection by providing debris basins and increased channel capacity. The channel is also designed to divert runoff into spreading basins for ground water recharge. c. ' Social well-being considerations. The well-being of the people in the project area will be improved because of flood protection that will reduce the possibility of loss of life, injury', disease, and inconvenience. -

South Coast AQMD Continues Smoke Advisory Due to Bobcat Fire and El Dorado Fire

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: September 16, 2020 MEDIA CONTACT: Bradley Whitaker, (909) 396-3456, Cell: (909) 323-9516 Nahal Mogharabi, (909) 396-3773, Cell: (909) 837-2431 [email protected] South Coast AQMD Continues Smoke Advisory Due to Bobcat Fire and El Dorado Fire Valid: Wednesday, September 16, through Thursday, September 17, 2020 This advisory is in effect through Thursday evening. South Coast AQMD will issue an update if additional information becomes available. Two major local wildfires as well as wildfires in Northern and Central California are affecting air quality in the region. A wildfire named the Bobcat Fire is burning north of Azusa and Monrovia in the Angeles National Forest. As of 6:50 a.m. on Wednesday, the burn area was approximately 44,393 acres with 3% containment. Current information on the Bobcat Fire can be found on the Incident Information System (InciWeb) at https://inciweb.nwcg.gov/incident/7152. A wildfire named the El Dorado Fire is burning in the San Bernardino Mountains near Yucaipa in San Bernardino County. As of 6:51 a.m. on Wednesday, the burn area was reported at 18,092 acres with 60% containment. Current information on the El Dorado Fire can be found on the Incident Information System at: https://inciweb.nwcg.gov/incident/7148/. In addition, smoke from fires in Central California, Northern California, Oregon, and Washington are also being transported south and may impact air quality in the South Coast Air Basin and Coachella Valley. Past and Current Smoke and Ash Impacts Both the Bobcat Fire and the El Dorado fires are producing substantial amounts of smoke on Wednesday morning. -

Microsoft Outlook

Vaida Pavolas From: [email protected] Sent: Monday, September 11, 2017 2:17 PM To: Mike Nichols; Ginger Marshall; David Zito; Jewel Edson; Judy Hegenauer; Amy Uruburu; City Attorney; Angela Ivey; Vaida Pavolas; Bill Chopyk; Corey Andrews Cc: [email protected] Subject: Redflex contract proposed renewal Follow Up Flag: Follow up Flag Status: Completed To the Honorable Solana Beach Officials, I believe you should terminate the Redflex Photo Light Enforcement Program and remove the cameras for several reasons. 1) The program does serious economic damage to the businesses in Solana Beach, their existing and potential employees, and ultimately to your tax base. Per the Federal Reserve, money circulates about six times a year. About $350 per ticket goes to Arizona, Australia and Sacramento to produce about 6 x $350 = $2,100 of total sales of goods and services (turnover) in a year. Almost none of that turnover can occur in the Solana Beach economic area because most of that money is gone forever. If about 3,000 citations are paid in a year, this means about 3,000 x $2,100 = $6,300,000 of sales of goods and services will occur in Arizona, Australia, and wherever Sacramento spends their portion of each ticket's revenue. Obviously, not all of that turnover would occur in the Solana Beach area, but some significant portion would - and the program prevents that turnover from having a chance to happen in your economic community because the money is gone. 2) These 79 California cities were reported to have dropped red light cameras, or prohibited them before any were installed. -

Fiscal Years 2021 & 2022 Cucamonga Valley Water

CUCAMONGA VALLEY WATER DISTRICT RANCHO CUCAMONGA, CA BUDGET FISCAL YEARS 2021 & 2022 CUCAMONGA VALLEY WATER DISTRICT TABLE OF CONTENTS BUDGET MESSAGE ....................................... 3 Debt .............................................................................................99 District-Wide Goals and Strategies ........................................ 4 DEPARTMENT INFORMATION .................. 102 Notable accomplishments ......................................................... 5 Position Summary Schedule ..................................................103 Short-Term Factors Influencing the Budget .......................... 5 Departmental Descriptions ..................................................105 Significant Budgetary Items ...................................................... 6 Executive Division .................................... 106 Budget Overview ........................................................................ 8 Board of Directors .................................................................107 Resolution NO. 2020-6-1 ........................................................10 Office of the General Manager ............................................109 Goals & Objectives ...................................................................11 Administrative Services Division ............. 111 Budget Guide .............................................................................14 Office of the Assistant General Manager ...........................112 History & Profile .......................................................................16 -

Listing of Self-Governed Special Districts San Bernardino County

Listing of Self-Governed Special Districts San Bernardino County Presented courtesy of the Local Agency Formation Commission for San Bernardino County 215 North D Street, Suite 204 San Bernardino, CA 92415-0490 (909) 383-9900; FAX (909) 383-9901 E-mail: [email protected] Web Site: www.sbclafco.org Updated July 2013 LISTING OF SELF-GOVERNED SPECIAL DISTRICTS SAN BERNARDINO COUNTY TABLE OF CONTENTS Page AIRPORT DISTRICTS 2 CEMETERY DISTRICTS 3 COMMUNITY SERVICES DISTRICTS 4 FIRE PROTECTION DISTRICTS 10 HEALTHCARE DISTRICTS 14 MOSQUITO ABATEMENT & VECTOR CONTROL DISTRICTS 16 RECREATION AND PARK DISTRICTS 17 RESOURCE CONSERVATION DISTRICTS 18 SANITATION DISTRICT 19 WATER DISTRICTS MUNICIPAL WATER DISTRICTS 20 WATER CONSERVATION DISTRICTS 22 WATER DISTRICTS 23 SPECIAL ACT WATER AGENCIES 32 ASSOCIATION OF THE SAN BERNARDINO COUNTY SPECIAL DISTRICTS 34 1 Local Agency Formation Commission, County of San Bernardino 215 North D Street, Suite 204, San Bernardino, CA 92415-0490 AIRPORT DISTRICTS BIG BEAR AIRPORT DISTRICT CONTACT: James “Pete” Gwaltney, Manager 3rd District Formed: 12/17/79 PHONE: (909) 585-3219 Powers: Airport FAX: (909) 585-2900 EMAIL: [email protected] Office Hours: WEBSITE: www.bigbearcityairport.com M – F 7:00 am – 6:00 pm Sat & Sun 8:00 am – 5:00 pm MAIL: P.O. Box 755 Big Bear City, CA 92314 OFFICE: 501 Valley Boulevard Big Bear City, CA 92314 Board of Directors Title Name Term End Date President Julie Smith 2016 Vice President Gary Stube 2014 Director Steve Castillo 2016 Director Steve Baker 2014 Director Chuck Knight 2016 YUCCA VALLEY AIRPORT DISTRICT CONTACT: Chris Hutchins, Board President 3rd District Robert “Bob” Dunn, Vice President/Manager Formed: 6/7/82 Powers: Airport PHONE: (760) 401-0816 FAX: (760) 228-3152 EMAIL: [email protected] Office Hours: WEBSITE: www.yuccavalleyairport.com M – F 8:00 am – 5:00 pm MAIL: P.O. -

Scott Zylstra: “Late Cretaceous Metamorphic and Plutonic of Proterozoic Metasediments of Ontario Ridge, Eastern San Gabriel

LATE CRETACEOUS PLUTONIC AND METAMORPHIC OVERPRINT OF PROTEROZOIC METASEDIMENTS OF ONTARIO RIDGE, EASTERN SAN GABRIEL MOUNTAINS, CALIFORNIA A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State Polytechnic University, Pomona In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science In Geological Sciences By Scott B. Zylstra 2017 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many thanks to Drs. Jonathan Nourse and Nicholas Van Buer for countless hours in research, assistance and editing on this project; to Zhan Peng, Anthony LeBeau and Karissa Vermillion for laboratory assistance; to the MENTORES program and the Cal Poly Geology Department for funding; to Joshua Schwartz and Carl Jacobson for valuable insight; and to Jennifer, Gwendolyn and Lydia Jean Zylstra, without whom this work would not be possible (and with whom sometimes has been scarcely possible). iii ABSTRACT The rifting of Rodinia, particularly in western Laurentia, has been a longstanding geologic problem, as Proterozoic rocks in the western U.S. are few and far between. The eastern San Gabriel Mountains contain a large metasedimentary package that has never been dated or thoroughly mapped. We present U-Pb detrital zircon geochronology results of 439 grains dated at CSUN’s LA-ICPMS; also 24 plutonic grains and 19 metamorphic rims of detrital grains analyzed on Stanford’s SHRIMP-RG, along with a detailed map, cross section and stratigraphic column for these Ontario Ridge metasediments. Probability plots of 206Pb/207Pb ages for five quartzite samples show three distinct peaks at ~1200, 1380-1470 and 1740-1780 Ma. Maximum depositional age is constrained by 3 grains between 906 to 934 Ma, which are 11-28% discordant. -

Southern California National Forests Inventoried Roadless Area (IRA) Analysis (Reference FSH 1909.12-2007-1, Chapter 72) Cucamonga B San Bernardino National Forest

Southern California National Forests Inventoried Roadless Area (IRA) Analysis (Reference FSH 1909.12-2007-1, Chapter 72) Cucamonga B San Bernardino National Forest Overview • IRA name o Cucamonga B o 11,882 acres • Location and vicinity, including access by type of road or trail o The Cucamonga B Inventoried Roadless Area is located within the western portion of the Front Country Ranger District of the San Bernardino National Forest. It is bounded on the west primarily by the existing Cucamonga Wilderness; on the south by National Forest System Road (NFSR) 1N34 Cucamonga Truck Trail; on the east side by private land in Lytle Creek, NFSR 2N57, and 2N58; and on the north by NFSR 3N06. Cucamonga B is separated from the Cucamonga C Inventoried Roadless Area by Day Canyon. This area is comprised of the upper Lytle Creek and Cucamonga Creek watersheds. It lies west of the rural community of Lytle Creek, with the more larger, more urbanized Rancho Cucamonga and Upland communities located in the valley about one mile south. • Geography, topography and vegetation (including the ecosystem type(s) o Cucamonga B contains steep, heavily dissected ridges with dense chaparral ecosystems and some riparian areas in the lower elevations and mixed conifer in the upper elevations. Elevations range from about 3,000 to 7,800 feet with an aspect that varies. Topography is steep from Lytle Creek west up towards the boundary with the Angeles National Forest. o A few minor, intermittent streams are present along with some of the perennial North, Middle and South Forks of Lytle Creek. -

South Coast AQMD Continues Advisory Due to Smoke from California Wildfires

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: August 25, 2021 MEDIA CONTACTS: Bradley Whitaker, (909) 396-3456, Cell: (909) 323-9516 Nahal Mogharabi, (909) 396-3773, Cell: (909) 837-2431 [email protected] South Coast AQMD Continues Advisory Due to Smoke from California Wildfires Valid: Wednesday, August 25 through Friday, August 27, 2021 This advisory is in effect through Friday morning. South Coast AQMD will issue an update if additional information becomes available. Wildfires in northern and central California are producing heavy smoke that is being transported into the South Coast Air Basin and the Coachella Valley. While the heaviest smoke will be present in the upper atmosphere across the region, the greatest impacts on surface air quality are expected in mountain areas, the Inland Empire, and the Coachella Valley. Smoke impacts are expected to continue until Thursday evening. Smoke levels are expected to continue decreasing throughout Wednesday afternoon and during the day on Thursday. During this period, the PM2.5 concentration may be moderately elevated and reach Unhealthy for Sensitive Groups Air Quality Index (AQI) levels in mountain areas, the Inland Empire, and the Coachella Valley. Ozone, the predominant summertime pollutant, may reach Unhealthy AQI levels near Crestline, Fontana, Redlands, San Bernardino, and Upland. To help keep indoor air clean during periods of poor air quality, close all windows and doors and run your air conditioner and/or an air purifier. If possible, do not use whole house fans or swamp coolers that bring in outside air. Avoid burning wood in your fireplace or firepit and minimize sources of indoor air pollution such as candles, incense, pan-frying, and grilling. -

San Bernardino Valley Municipal Water Districts Water Supply Contract

STATE OF CALIFORNIA THE RESOURCES AGENCY OF CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF WATER RESOURCES WATER SUPPLY CONTRACT BETWEEN THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF WATER RESOURCES AND SAN BERNARDINO VALLEY MUNICIPAL WATER DISTRICT Disclaimer: This document integrates San Bernardino Valley Municipal Water District’s State Water Project water supply contract and amendments to the contract entered into since December 30, 1960. It is intended only to provide a convenient reference source, and the Department of Water Resources is unable to provide assurances that this integrated version accurately represents the original documents. For legal purposes, or when precise accuracy is required, users should direct their attention to original source documents rather than this integrated version. (Incorporates through Amendment No. 17, executed May 28, 2003) (No other amendments through 2017) EXPLANATORY NOTES This symbol encloses material not contained in < > the original or amended contract, but added to assist the reader. Materials that explain or provide detailed Exhibits information regarding a contract provision. Materials that implement provisions of the basic Attachments contract when certain conditions are met. Amendments have been incorporated into this Amendments consolidated contract and are indicated by footnote. This Water Supply Contract used the term District Name “District” in the original contract for this contractor. Some amendments may not have retained the same nomenclature. This consolidated contract uses the term “District” to be consistent with the original contract. It does not change the content meaning. This Water Supply Contract used the term “State” in the original contract for this contractor. Some Department Name amendments may not have retained the same nomenclature. This consolidated contract uses the term “State” throughout to be consistent with the original contract. -

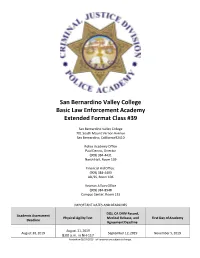

Extendedacademyfinalpacketcla

San Bernardino Valley College Basic Law Enforcement Academy Extended Format Class #39 San Bernardino Valley College 701 South Mount Vernon Avenue San Bernardino, California 92410 Police Academy Office Paul Dennis, Director (909) 384-4431 North Hall, Room 139 Financial Aid Office: (909) 384-4403 AD/SS, Room 106 Veteran Affairs Office (909) 384-8948 Campus Center, Room 133 IMPORTANT DATES AND DEADLINES DOJ, CA DMV Record, Academic Assessment Physical Agility Test Medical Release, and First Day of Academy Deadline Agreement Deadline August 31, 2019 August 30, 2019 September 12, 2019 November 5, 2019 8:00 a.m. in NH-117 Revised on 08/24/2018 – all contents are subject to change. SAN BERNARDINO VALLEY COLLEGE (SBVC) BASIC LAW ENFORCEMENT ACADEMY – EXTENDED FORMAT “52” WEEKS The next Extended Academy will be Class #39 and will begin November 5, 2019. Classes meet Tuesday and Thursday evenings from 5:30 p.m. to 10:30 p.m. and Saturdays from 8:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. for a total of 52 weeks. (Some Saturdays will be rescheduled to Sundays with advanced notice.) Anyone interested in attending the Extended Academy as a Pre- Service trainee must complete the following eligibility requirements: POLICE ACADEMY ADMISSIONS AND POLICY A. Applicants shall be admitted to the San Bernardino Valley College Police Academies in the fall term each year. In addition to the general requirements for admission to the college, Police Academy pre-service applicants shall be admitted to the Police Academy Program subject to the provisions of this policy. B. Pre-Admission Requirements and Sequence 1. -

Geologic Map of the Cucamonga Peak 7.5' Quadrangle, San Bernardino County, California

Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. FOREST SERVICE (San Bernardino National Forest) OPEN-FILE REPORT 01-311 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR and the CALIFORNIA DIVISION OF MINES AND GEOLOGY U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Version 1.0 DESCRIPTION OF MAP UNITS 117 37' 30" MODERN SURFICIAL DEPOSITS—Sediment recently transported and Lookout (Kt), west of Lytle Creek 117 30' CORRELATION OF MAP UNITS 34 15' 34 15' deposited in channels and washes, on surfaces of alluvial fans and alluvial plains, Kssm Mylonitized tonalite of San Sevaine Lookout (Cretaceous)—Gneissic and and on hillslopes. Soil-profile development is non-existant to minimal. Includes: mylonitic tonalite; mylonitic deformation discontinuously distributed Qw Very young wash deposits (late Holocene)—Unconsolidated coarse-grained sand throughout unit. Consists of mixture of Kssm1 and Kss Tonalite of San Sevaine Lookout (Cretaceous)—Hornblende-biotite tonalite, to bouldery alluvium of active channels and washes flooring drainage bottoms Kssm1 within mountains and on alluvial fans along base of mountains. Most alluvium possibly ranging to granodiorite and quartz diorite. Foliated, gray, medium- to Qw Qf Qc Qls is, or recently was, subject to active stream flow. Includes some low-lying coarse-grained; generally equigranular, but locally sub-porphyritic, containing terrace deposits along alluviated canyon floors and areas underlain by colluvium small, poorly formed feldspar phenocrysts. Foliation defined by oriented ? ? Qf1 along base of some slopes hornblende and biotite, commonly as dark, multi-grained, flattened inclusions. Very young alluvial fan deposits (late Holocene)—Unconsolidated deposits of Contains large septa of marble, gneiss, and schist, the latter two incorporated in Qyf5 Qf Holocene coarse-grained sand to bouldery alluvium of modern fans having undissected varying degree into the tonalite; some rock contains scattered garnets having kelyphytic rims.