War and Peace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pevensey and Cuckmere Water Level Management Board Order 2016

Certified copy from legislation.gov.uk Publishing STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2016 No. 854 LAND DRAINAGE, ENGLAND The Pevensey and Cuckmere Water Level Management Board Order 2016 Made - - - - 22nd August 2016 Coming into force - - 1st October 2016 Under section 3(1)(a) of the Land Drainage Act 1991 (“the 1991 Act”)( a), the Environment Agency has prepared a Scheme making provision for the matters specified in section 3(2)(d),(e), (f),(g) and (i)( b) and has submitted the Scheme to the Secretary of State for confirmation. The Secretary of State has published a notice of intent to make this Order confirming the Scheme in accordance with paragraph 2(1) of Schedule 3 to the 1991 Act and has sent this notice to the relevant local authorities and other bodies specified in paragraph 2(2) of that Schedule. No objection has been made to the draft Order. Accordingly, the Secretary of State makes this Order in exercise of the powers conferred by section 3(5) and (7) of the 1991 Act and now vested in the Secretary of State( c). Citation, commencement and interpretation 1. —(1) This Order may be cited as the Pevensey and Cuckmere Water Level Management Board Order 2016 and comes into force on 1st October 2016. (2) In this Order, “the Agency” means the Environment Agency. Confirmation of the Scheme with modifications 2. —(1) The Scheme submitted by the Agency is confirmed with modifications. (2) The Scheme as modified by the Secretary of State is set out in the Schedule to this Order. Secretary of State’s expenses 3. -

Alfriston Village Much Ado Books, Is an Award-Winning Independent Bookshop Situated in ALFRISTON Alfriston, Offering a Hand-Picked Selection of Both New and Old Books

Much Ado Books Alfriston Village Much Ado Books, is an award-winning independent bookshop situated in ALFRISTON Alfriston, offering a hand-picked selection of both new and old books. www.muchadobooks.com/ Badgers Tea House BISC Alfriston was granted its market charter in 1406, and the Alfriston and the Cuckmere Valley house at the Old Village Bakery Minibus Destination Take a trip to Alfriston to explore the historic heritage of the dates from 1510. It was the village and the natural beauty of the surrounding countryside. village bakery for 200 years Stroll along the Cuckmere river or up onto the Downs to soak until 1933 – village residents up the peace and tranquillity of the area. used to bring cakes to bake to their local bakery (it was run by Alfriston is surrounded by the Wealden South Downs and the Richard Harryott in the 1700s, South Downs Way passes through the centre of known as Doughy!), but once this historical village. domestic ovens were affordable, many villages lost Around the village, visitors can enjoy their famous church (The Cathedral of the South Downs), clergy house along with galleries, their bakery. cafes, pubs and boutiques offering a wide range of gifts, from unusual chocolates to music memorabilia. Drink tea from fine bone china cups, poured from silver Alfriston hosts many events throughout the year including music festivals, traditional fetes, boot fairs ... the list seems endless. teapots, in a lovely walled Keep an eye on the website noted below for information. garden if the weather’s good, or in the cosy tea room if it’s https://www.alfriston-village.co.uk/ cooler, and enjoy freshly baked The village of Alfriston is steeped in history, and has scones and perfect cakes. -

The Old Manse, High Street, Alfriston, Price Guide - £430,000

The Old Manse, High Street, Alfriston, Price Guide - £430,000 Viewing strictly by appointment The Old Manse, High Street, Alfriston, East Sussex BN26 5SZ An extremely rare residential and commercial opportunity in the downland village of Alfriston - A charming period property overlooking Warrior Square presently run as a highly successful antique showroom with self-contained living accommodation above Ground floor accommodation comprises 28’ x 12’ principal show room ♦ office ♦ utility area ♦ separate wc Self-contained first floor apartment with private courtyard garden ♦ large entrance hall and utility lobby with large cellar below and staircase to first floor ♦ ♦ charming sitting room spacious open plan luxuriously fitted kitchen/dining room bedroom suite comprising double bedroom and luxurious bathroom/wc Ground Floor Accommodation comprises Charming Sitting Room 15'4” x 13' (4.67m x 3.96m) Description An extremely rare residential and Principal Show Room 28’10” x 12’10” (8.79m x 3.91m) into the recesses flanking the fireplace , beamed ceiling, commercial opportunity in the downland village of reducing to 9’8” (2.95m) at the rear featuring an open range of fitted adjustable book shelving, radiator. Alfriston - A charming period property overlooking fireplace, beamed ceilings and a double aspect with Warrior Square presently run as a highly successful windows to the front and side. Double Bedroom 1 14'9” x 9'6” (4.50m x 2.90m) to antique showroom with self-contained living accommodation above . This Grade II listed freehold include -

Bus Route 47 Cuckmere Valley Ramblerbus

47 Cuckmere Valley Ramblerbus Saturdays, Sundays & Public Holidays during British Summer Time (until 31 October 2021) An hourly circular service from Berwick station via Alfriston, Seaford, Seven Sisters Country Park, Litlington and Wilmington. Temporary Timetable during closure of Station Road, Berwick Service 47 is affected by the long term closure of Station Road, Berwick and will operate to the temporary timetable shown below. Wilmington is not served by this temporary timetable. Please check Service Updates for the latest information. 47 on Saturdays Train from Brighton & Lewes 0956 1756 Train from Eastbourne 0954 1754 ------ ------ Berwick Station 1000 1800 Berwick Crossroads 1005 1805 Berwick, Drusillas Park 1006 1806 Alfriston Market Cross 1010 1810 Alfriston, Frog Firle 1012 and 1812 High & Over Car Park 1014 then 1814 Chyngton Estate, Millberg Rd 1016 hourly 1816 Sutton Avenue, Arundel Rd 1016 until 1819 Seaford, Morrisons (near stn) 1021 1821 Seaford, Library 1022 1822 Seaford, Sutton Corner 1024 1824 Exceat, Cuckmere Inn 1027 1827 Seven Sisters Country Park Centre 1029 1829 Friston Forest, West Dean Car Pk 1031 1831 Litlington, Plough & Harrow 1035 1835 Lullington Corner 1037 1837 Drusillas Roundabout 1041 1841 Berwick Crossroads 1042 1842 Berwick Station 1047 1847 ------ ------ Train to Lewes & Brighton 1054 1854 Train to Eastbourne 1056 1856 Seaford trains: ------ ------ ... arrive from Brighton & Lewes 0948 1748 ... depart to Lewes & Brighton 1026 1826 In the rural area the bus will stop to pick up or set down wherever it is safe to do so. At Berwick Station the bus will wait for up to 5 minutes for a late running train. Train times may be different on Bank Holidays, please check before travelling. -

Vanguard Cottage 6Pp Landscape

CHALVINGTON BRAMBLE COTTAGE VANGUARD COTTAGE Vanguard Cottage is a delightful detached four bedroom property sitting within the expansive grounds of Mount Pleasant farm. It is located down a long well kept driveway , flanked at the sides by poplar trees. It offers stunning far reaching views to the South Downs and Firle Beacon. The Cottage has its own driveway with off road parking and private gardens with fruit trees. It has been refurbished and offers country living in a contemporary style. The entrance leads to the open plan dining area with views across the gardens, the lounge has a cosy feel with its wood burner, there is a light spacious kitchen with Rayburn double oven and breakfast area with patio doors to the garden. The utility room with its own entrance, allows for keeping the kitchen more minimalist. A downstairs shower room and study are an added feature. There are doors to the rear with a decked veranda. Upstairs are four bedrooms with views across the fields and nearby countryside. The family bathroom and separate WC all make this a fabulous family home. The pretty garden with its fruit trees, is private and enclosed by hedges and fencing, in total around 0.3 acres (tbv). There is an extra plot of land to the front of the cottage also. A fabulous family home with further potential to extend and plans currently submitted. AT A GLANCE.… SITUATION ● Detached Cottage The village of Chalvington is set ● Four Bedrooms within the Wealden district of East Sussex. It is also mentioned in the ● Living Room with Wood Burner Domesday book, and was twinned ● Open Plan Dining Area with Ripe. -

IDB Biodiversity Action Plan

BIODIVERSITY ACTION PLAN April 2018 PEVENSEY AND CUCKMERE WLMB – BIODIVERSITY ACTION PLAN Front cover images (L-R) Kestrel ©Heather Smithers; Barn Owl; Floating Pennywort; Fen Raft Spider ©Charlie Jackson; Water Vole; Otter PEVENSEY AND CUCKMERE WLMB – BIODIVERSITY ACTION PLAN FOREWORD This Biodiversity Action Plan has been prepared by the Pevensey and Cuckmere Water Level Management Board in accordance with the commitment in the Implementation Plan of the DEFRA Internal Drainage Board Review for IDB’s, to produce their own Biodiversity Action Plans by April 2010. This aims to align this BAP with the Sussex Biodiversity Action Plan. The document also demonstrates the Board’s commitment to fulfilling its duty as a public body under the Natural Environment and Rural Communities Act 2006 to conserve biodiversity. Many of the Board’s activities have benefits and opportunities for biodiversity, not least its water level management and ditch maintenance work. It is hoped that this Biodiversity Action Plan will help the Board to maximise the biodiversity benefits from its activities and demonstrate its contribution to the Government’s UK Biodiversity Action Plan targets as part of the Biodiversity 2020 strategy. The Board has adopted the Biodiversity Action Plan as one of its policies and subject to available resources is committed to its implementation. It will review the plan periodically and update it as appropriate. Bill Gower Chairman of the Board PEVENSEY AND CUCKMERE WLMB – BIODIVERSITY ACTION PLAN CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS & ACRONYMS 1 1 -

Berwick House, Berwick, East Sussex Chilver Bridge Road, the Reception Rooms Are Ideally Arranged for Formal and Informal Entertaining

Berwick House, Berwick, East Sussex Chilver Bridge Road, The reception rooms are ideally arranged for formal and informal entertaining. Berwick, East Sussex, Internally, the house has a charming ambience BN26 6SD and provides excellent accommodation arranged over two floors. On entering this A stunning late-Victorian house with property, you have a feeling of grandeur with secondary accommodation and a characteristic large Victorian style entrance hall opening into a sitting area with a feature uninterrupted views to the South Downs. hexagonal window. Designed by a London based company, the Berwick Station 0.3 mile, Alfriston 2.3 miles, 30’5” bespoke kitchen/dining/family room is a Lewes 8.5 miles, Eastbourne 9 miles, superb family area offering modern day living. London 75 miles The kitchen is fitted with a range of bespoke painted units with honed granite work surfaces Main House: Covered entrance porch l Entrance hall l Drawing room l Sitting room l Magnificent and includes a three oven electric Aga with 30’ kitchen/dining/family room l Cloakroom gas hob. There is the added advantage of Principal suite comprising bedroom, bathroom underfloor heating to the majority of the and walk-in wardrobe l Guest suite comprising ground floor. bedroom and shower room l Three further bedrooms l Further bathroom | EPC Rating E The triple aspect drawing room has a feature fireplace with a Charnwood Island wood burner Guest Cottage: Large studio/bedroom with and a renovated wood floor with French doors kitchen area l Wet room | EPC Rating D leading out to the terrace. In addition, there is a well-proportioned reading area. -

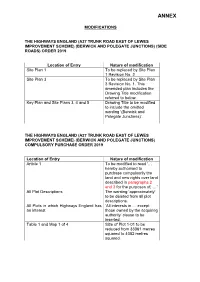

Berwick and Polegate Junctions) (Side Roads) Order 2019

ANNEX MODIFICATIONS THE HIGHWAYS ENGLAND (A27 TRUNK ROAD EAST OF LEWES IMPROVEMENT SCHEME) (BERWICK AND POLEGATE JUNCTIONS) (SIDE ROADS) ORDER 2019 Location of Entry Nature of modification Site Plan 1 To be replaced by Site Plan 1 Revision No. 2 Site Plan 3 To be replaced by Site Plan 3 Revision No. 1. This amended plan includes the Drawing Title modification referred to below. Key Plan and Site Plans 3, 4 and 5 Drawing Title to be modified to include the omitted wording ‘(Berwick and Polegate Junctions)’. THE HIGHWAYS ENGLAND (A27 TRUNK ROAD EAST OF LEWES IMPROVEMENT SCHEME) (BERWICK AND POLEGATE JUNCTIONS) COMPULSORY PURCHASE ORDER 2019 Location of Entry Nature of modification Article 1 To be modified to read ‘… hereby authorised to purchase compulsorily the land and new rights over land described in paragraphs 2 and 3 for the purposes of; …’ All Plot Descriptions The wording ‘approximately’ to be deleted from all plot descriptions. All Plots in which Highways England has ‘All interests in … except an interest those owned by the acquiring authority’ clause to be inserted. Table 1 and Map 1 of 4 Size of Plot 1-01 to be reduced from 33061 metres squared to 4082 metres squared. Location of Entry Nature of modification Table 1 H J Hecks and Sons to be added in to Plot 1-01 as tenant occupiers. Francis Nation-Dixon, Robin Sanford Holden Illingworth and Unknown to be deleted as occupiers. ‘(as trustee of the Firle Estate)’ to be inserted in the ‘Owners or Reputed Owners’ column under Francis Nation-Dixon and Robin Sanford Holden Illingworth. -

The Underground Water-Levels of The

342 WAITLEY ON UNDERGROUND WATER-LEVELS. [Selected (Paper No. 3228.) ‘‘ ‘I he Underground Water-Levels of the South Downs between Eastbourne and the River Cu~kmere.” By HENRYNICHELL WHITLEY, N. Inst. C.E. THE portion of the South Downs of Sussex referredto in the following Paper is the extremeeastern knoll, stretching from Eastbourne and Polegate on the east to the River Cuckmere on the west, and from theEnglish Channel on the south tothe Weald on the north, being about 5 miles in extent from east to west, and about 6 miles from north to south, Fig. 1. The hills rise considerably from the low land around, the highest portions being the eastern and northern escarpments, the ground having a steep slope towards the marshes and the Weald, and a more gradual one to the south and west. The district is bounded on the south by a lofty range of cliffs, of which Beachy Head is the highest part, being 536 feet above Ordnance datum. Northward from this point the escarpment varies between 500 feet and 600 feet, to Willingdon Hill, which has a height of 665 feet above Ordnance datum. Coomb Hill, at the north-east angle, is 638 feet, whilst Wilmington Hill, at the north-west end of the ridge, is 704 feet above Ordnance datum. The principal valley runs from that of the River Cuckmere by Westdean and Friston Place to Jevington Village, where there is a saddleback in the escarpment, about 290 feet above Ordnance datum; here it meets the deeply cut Wannock (or Filching) Glen, leading to the Weald. -

Osprey Trail

Arlington Reservoir Arlington Reservoir Osprey Trail Local Nature Reserve Osprey Badgers Kingfisher Way Marker 1 Way Marker 4 Way Marker 6 In front of you is our bird feeding area, where you In front of way marker 4 is a “laid hedge”. This has Arlington reservoir is called a pumped storage can stop, feed and observe many different species been created using a traditional technique know as reservoir. Water is pumped into the reservoir from of wildfowl. It’s a great way to see the birds close up. hedge-laying. Hedge-laying was once a common sight the River Cuckmere during times of surplus and To the left and right of the bird feeding area, reeds in the Sussex countryside. Hedgelaying involves stored here. (Phragmites Australis) have been planted. selecting and laying suitable stems called pleachers. In front of you is a building known as a valve tower, The reedbeds form an important habitat for wildlife These are cut to leave sufficient cambium and it has three draw off points which are used to abstract as well as helping to protect the reservoir banks sapwood uncut to allow the pleacher to bend and to water from the reservoir so that it can be treated for from erosion. survive. Stakes and binding (heatherings) are then drinking water. added to strengthen the newly laid hedge The reedbed provides nesting and feeding habitats for (see diagram below). The water from the reservoir is treated at our nearby many birds including wagtails, warblers, kingfishers water treatment works using various filtration and and wildfowl. The laid hedge in front of you is home to many species treatment techniques. -

MINERALS & FRUIT JUICES Kingsdown Sparkling Pressés – Kent

MINERALS & FRUIT JUICES CHAMPAGNE & SPARKLING WINES Kingsdown Sparkling Pressés – Kent 330ml Bottle 500ml 175ml 125ml Cloudy Lemonade £4.50 Canard Duchene, Champagne £55.00 n/a £14.60 £10.40 Orange £4.50 Cuvee Leonie NV Rhubarb £4.50 Bluebell Vineyards Sheffield Park £46.00 n/a £12.50 £9.00 Elderflower £4.50 Hindleap Seyval Blanc 2013 Blackcurrant £4.50 Nyetimber Classic West Chillington £85.00 n/a £20.00 £14.15 Fevertree, Premium Mixers Cuvee Indian Tonic 200ml £4.25 Rathfinny Wine Alfriston £75.00 n/a £19.50 £14.00 Slimline Tonic 200ml £4.25 Estate Rose Brut 2016 Appletiser 200ml £3.90 Canada Dry 125ml £3.30 Coke 200ml £3.90 ROSE WINE Coke Zero 200ml £3.90 Bluebell Vineyards Sheffield Park £45.00 £30.00 £10.00 £7.10 Southdown Water 330ml 750ml Ashdown Rose 2018 Still £3.10 £4.95 Sparkling £3.10 £4.95 WHITE WINE BEERS, ALES & CIDERS 500ml Bluebell Vineyards Sheffield Park £44.00 £28.00 £10.00 £7.10 Ashdown Bacchus Bedlam Pilsner Plumpton £5.50 Bedlam Porter Plumpton £5.50 Hidden Spring Heathfield £52.00 £35.00 £12.20 £8.75 Vineyard Bedlam Pale Plumpton £5.50 Chardonnay Harvey's Best Bitter Lewes £6.10 Chapel Down Dry Tenterden £56.00 £34.00 £13.10 £9.35 Longmans Best Bitter Polegate £6.40 Flint Silly Moo Cider Horsham £8.30 Bolney Pinot Gris Haywards Heath £43.00 £28.00 £11.60 £8.15 2018 GIN 50ml 25ml Rathfinny Estate Alfriston £50.00 £33.00 £12.00 £8.50 Cradle Valley White Mayfield Gin Mayfield £11.00 £5.55 CJ Pask Sauvignon New Zealand £42.00 £32.00 £11.20 £7.85 Tom Cat Sussex Gin Crowborough £9.50 £4.90 Blanc, Seven Sisters Gin Alfriston -

| Things to Do and See |

| THINGS TO DO AND SEE | Gravetye Manor Vowels Lane, West Hoathly, Sussex, RH19 4LJ Telephone (01342) 810567 E-mail [email protected] www.gravetyemanor.co.uk Gravetye Manor is a smallm country house hotel set in 1000 acresacre of wooded parklands andnd gardens,gardens, famofamous for being createdted byby William Robinson, arguably onee off EEngland’sngland’s greatestgreatest gardeners.gard “...beautyauty was never lost sightsight of;o nothing was done without consideringconside its effectct on the landscalandscapep from everyry poipointnt of view...” William Robinsonbinson on Gravetye - 1918 Michelin Star | XXX | | CONTENTS | As a guest at Gravetye Manor, we want you to get the most out of your stay with us. We hope this guide will compliment and enrich your stay at Gravetye with little extra ideas for you to fill your time with. Gravetye can spoil you with a wealth of things to do and see whilst here. Our staff are always on hand and happy to help or advise with any queries you may have regarding activities in and around the Manor. Please enjoy. | At Gravetye | 4 | Activities nearby | 8 | Local area | 11 | Local gardens | 14 | Historic houses | 16 | Eating out | 20 | Vineyards | 24 | Before you depart | 25 | Glyndebourne | 26 | Where we are | 27 | AT GRAVETYE | Gravetye’s peace and seclusion means whether you want to relax with a good book or take a stroll in the beautiful gardens there are still a number of things you can do on the estate. | Croquet | Picnics William Robinson’s playground, where To aide in the planning of your local children used to dance on his day we can arrange light picnics birthday and still do to commemorate of sandwiches, fresh fruit and cakes/ his special day, is a great spot for fun biscuits which can be eaten either croquet in the summer.