PM Singer Combined Dissertation 9.20.2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

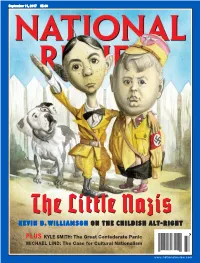

The Little Nazis KE V I N D

20170828 subscribers_cover61404-postal.qxd 8/22/2017 3:17 PM Page 1 September 11, 2017 $5.99 TheThe Little Nazis KE V I N D . W I L L I A M S O N O N T H E C HI L D I S H A L T- R I G H T $5.99 37 PLUS KYLE SMITH: The Great Confederate Panic MICHAEL LIND: The Case for Cultural Nationalism 0 73361 08155 1 www.nationalreview.com base_new_milliken-mar 22.qxd 1/3/2017 5:38 PM Page 1 !!!!!!!! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! "e Reagan Ranch Center ! 217 State Street National Headquarters ! 11480 Commerce Park Drive, Santa Barbara, California 93101 ! 888-USA-1776 Sixth Floor ! Reston, Virginia 20191 ! 800-USA-1776 TOC-FINAL_QXP-1127940144.qxp 8/23/2017 2:41 PM Page 1 Contents SEPTEMBER 11, 2017 | VOLUME LXIX, NO. 17 | www.nationalreview.com ON THE COVER Page 22 Lucy Caldwell on Jeff Flake The ‘N’ Word p. 15 Everybody is ten feet tall on the BOOKS, ARTS Internet, and that is why the & MANNERS Internet is where the alt-right really lives, one big online 35 THE DEATH OF FREUD E. Fuller Torrey reviews Freud: group-therapy session The Making of an Illusion, masquerading as a political by Frederick Crews. movement. Kevin D. Williamson 37 ILLUMINATIONS Michael Brendan Dougherty reviews Why Buddhism Is True: The COVER: ROMAN GENN Science and Philosophy of Meditation and Enlightenment, ARTICLES by Robert Wright. DIVIDED THEY STAND (OR FALL) by Ramesh Ponnuru 38 UNJUST PROSECUTION 12 David Bahnsen reviews The Anti-Trump Republicans are not facing their challenges. -

Public Comments

Timestamp Meeting Date Agenda Item First and Last Name Zip Code Representing Comments It is inappropriate to use an obviously biased company for Arizona’s redistricting mapping process. Bernie Sanders and Barack Obama should have zero say in what our maps look like, and these companies are funded by them at the national level. We want you to hire the National Demographics Corporation – Douglas Johnson in order to assure Arizonans of fair representation and elections. The “Independent” Review Council should make amends for ten years of incompetence and corruption. The commissioners met as many as five times at the home of the AZ 4/27/2021 9:12:25 April 27, 2021 Redistricting Marta 85331 Democratic Party’s Executive Director! It is inappropriate to use an obviously biased company for Arizona’s redistricting mapping process. Bernie Sanders and Barack Obama should have zero say in what our maps look like, and these companies are funded by them at the national level. We want you to hire the National Demographics Corporation – Douglas Johnson in order to assure Arizonans of fair representation and elections. The “Independent” Review Council should make amends for ten years of incompetence Redistricting and corruption. The commissioners met as many as five times at the home of the AZ 4/27/2021 9:12:47 April 27, 2021 Company Michael MacBan 85331 Democratic Party’s Executive Director! I would l ke to request that the company to be hired is the National Demographics Corporation – Douglas Johnson, in order to assure Arizonans fair representation and redistricting elections. mapping It would be inappropriate to use a biased company for the redistricting mapping process. -

Congressional Directory UTAH

274 Congressional Directory UTAH UTAH (Population 2010, 2,763,885) SENATORS MICHAEL S. LEE, Republican, of Alpine, UT; born in Mesa, AZ, June 4, 1971; education: B.S., Brigham Young University, Provo, UT, 1994; J.D., Brigham Young University, 1997; pro- fessional: law clerk to Judge Dee Benson of the U.S. District Court for the District of Utah; law clerk to Judge Samuel A. Alito, Jr. on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit Court; attorney with the law firm Sidley & Austin; Assistant U.S. Attorney in Salt Lake City; general counsel to the Governor of Utah; law clerk to Supreme Court Justice Samuel A. Alito; partner at Howrey law firm; religion: Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints; married: Sharon Burr of Provo, UT; children: James, John, and Eliza; committees: chair, Joint Economic Committee; Commerce, Science, and Transportation; Energy and Natural Resources; Judiciary; elected to the U.S. Senate on November 2, 2010; reelected to the U.S. Senate on November 8, 2016. Office Listings https://lee.senate.gov https://facebook.com/senatormikelee https://twitter.com/SenMikeLee https://youtube.com/senatormikelee 361A Russell Senate Office Building, Washington, DC 20510 .............................................. (202) 224–5444 Chief of Staff.—Allyson Bell. FAX: 228–1168 Legislative Director.—Christy Woodruff. Communications Director.—Conn Carroll. Press Secretary.—Erik Kujanpaa. Administrative Director.—Alyssa Burleson. State Director.—Robert Axson. Federal Building, 125 South State, Suite 4225, Salt Lake City, UT 84138 ........................... (801) 524–5933 Federal Building, 324 25th Street, Suite 1410, Ogden, UT 84401 ......................................... (801) 392–9633 285 West Tabernacle Street, Suite 200, St. -

Research Report Report Number 704, November 2011 Nominating Candidates the Politics and Process of Utah’S Unique Convention and Primary System

Research Report Report Number 704, November 2011 Nominating Candidates The Politics and Process of Utah’s Unique Convention and Primary System HIGHLIGHTS For most of its history, Utah has used a convention- g Utah is one of only seven states that still uses a primary system to nominate candidates for elected office. convention, and the only one that allows political parties to preclude a primary election for major In the spring of election years, citizens in small caucus offices if candidates receive enough delegate votes. g Utah adopted a direct primary in 1937, a system meetings held throughout the state elect delegates to which lasted 10 years. represent them at county and state conventions. County g In 1947, the Legislature re-established a caucus- convention system. If a candidate obtained 80% or conventions nominate candidates for races solely within more of the delegates’ votes in the convention, he or she was declared the nominee without a primary. the county boundaries, while the state convention is used g In the 1990s, the Legislature granted more power to the parties to manage their conventions. In to nominate candidates for statewide offices or those 1996, the then-70% threshold to avoid a primary was lowered to 60% by the Democratic Party. The that serve districts that span multiple counties. At these Republican Party made the same change in 1999. conventions, delegates nominate candidates to compete g Utah’s historically high voter turnout rates have consistently declined in recent decades. In 1960, for their party’s nomination in the primary election, or, 78.3% of the voting age population voted in the general election. -

Minutes for House Government Operations Committee 03/06

MINUTES OF THE HOUSE PUBLIC UTILITIES & TECHNOLOGY STANDING COMMITTEE Room 20, House Building March 6, 2014 Members Present: Rep. Roger Barrus, Chair Rep. Steve Handy, Vice Chair Rep. Jerry Anderson Rep. Kay Christofferson Rep. Lynn Hemingway Rep. Angela Romero Rep. Robert Spendlove Rep. Curt Webb Rep. John Westwood Staff Present: Mr. Richard North, Policy Analyst Ms. Becky Paulson, Committee Secretary Note: A list of visitors is filed with the committee minutes. Vice Chair Handy called the meeting to order at 4:22 p.m. MOTION: Rep. Hemingway moved to approve the minutes of the March 5, 2014 meeting. The motion passed unanimously with Rep. Christofferson and Rep. Spendlove absent for the vote. S.B. 89 Amendments to Definition of Public Utility (Sen. S. Urquhart) (Rep. B. Last) Sen. Urquhart explained the bill. Spoke for the bill: Brad Shafer, Rocky Mountain Power Ray Torres, Department of Defense, Tooele Depot MOTION: Rep. Romero moved to pass the bill out favorably. The motion passed unanimously with Rep. Spendlove absent for the vote. 2nd Sub. S.B. 208 Public Utility Modifications (Sen. C. Bramble) (Rep. J. Dunnigan) Sen. Bramble explained the bill. MOTION: Rep. Webb moved to pass the bill out favorably. The motion passed unanimously. MOTION: Rep. Webb moved to place the bill on the Consent Calendar. The motion passed House Public Utilities & Technology Standing Committee March 6, 2014 Page 2 unanimously. S.B. 217 Public Utilities Amendments (Sen. K. Van Tassell) (Rep. J. Mathis) Sen. Van Tassell explained the bill. MOTION: Rep. Westwood moved to pass the bill out favorably. The motion passed unanimously. -

Utah's Official Voter Information Pamphlet

UTAH’S OFFICIAL VOTER INFORMATION PAMPHLET 2018 GENERAL ELECTION TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 6TH NOTE: This electronic version of the voter information pamphlet contains general voting information for all Utah voters. To view voting information that is specific to you, visit VOTE.UTAH.GOV, enter your address, and click on “Sample Ballot, Profiles, Issues.” For audio & braille versions of the voter information pamphlet, please visit blindlibrary.utah.gov. STATE OF UTAH OFFICE OF THE LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR SPENCER J. COX LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR Dear Utah Voter, My office is pleased to present the 2018 Voter Information Pamphlet. Please take the time to read through the material to learn more about the upcoming General Election on November 6, 2018. Inside you will find information about candidates, ballot questions, judges, and how to vote. In addition to this pamphlet, you can visit VOTE.UTAH.GOV to find even more information about the election. At VOTE.UTAH.GOV you can view your sample ballot, find your polling location, and view biographies for the candidates in your area. If you need assistance of any kind, please call us at 1-800-995-VOTE, email [email protected], or stop by our office in the State Capitol building. Thank you for doing your part to move our democracy forward. Sincerely, Spencer J. Cox Lieutenant Governor WHAT’S IN THIS PAMPHLET? 1. WHO ARE THE CANDIDATES? 2 U.S. Senate 3 U.S. House of Representatives 5 Utah State Legislature 9 Utah State Board of Education 28 2. WHAT ARE THE QUESTIONS ON MY BALLOT? 30 Constitutional Amendment A 32 Constitutional Amendment B 35 Constitutional Amendment C 39 Nonbinding Opinion Question Number 1 44 Proposition Number 2 45 Proposition Number 3 66 Proposition Number 4 74 3. -

Ebay Inc. Non-Federal Contributions: January 1 – December 31, 2018

eBay Inc. Non-Federal Contributions: January 1 – December 31, 2018 Campaign Committee/Organization State Amount Date Utah Republican Senate Campaign Committee UT $ 2,000 1.10.18 Utah House Republican Election Committee UT $ 3,000 1.10.18 The PAC MO $ 5,000 2.20.18 Anthony Rendon for Assembly 2018 CA $ 3,000 3.16.18 Atkins for Senate 2020 CA $ 3,000 3.16.18 Low for Assembly 2018 CA $ 1,000 3.16.18 Pat Bates for Senate 2018 CA $ 1,000 3.16.18 Brian Dahle for Assembly 2018 CA $ 1,000 3.16.18 Friends of John Knotwell UT $ 500 5.24.18 NYS Democratic Senate Campaign Committee NY $ 1,000 6.20.18 New Yorkers for Gianaris NY $ 500 6.20.18 Committee to Elect Terrence Murphy NY $ 500 6.20.18 Friends of Daniel J. O'Donnell NY $ 500 6.20.18 NYS Senate Republican Campaign Committee NY $ 2,000 6.20.18 Clyde Vanel for New York NY $ 500 6.20.18 Ben Allen for State Senate 2018 CA $ 1,000 6.22.18 Steven Bradford for Senate 2020 CA $ 1,000 6.22.18 Mike McGuire for Senate 2018 CA $ 1,000 6.22.18 Stern for Senate 2020 CA $ 1,000 6.22.18 Marc Berman for Assembly 2018 CA $ 1,000 6.22.18 Autumn Burke for Assembly 2018 CA $ 1,000 6.22.18 Ian Calderon for Assembly 2018 CA $ 1,000 6.22.18 Jim Cooper for Assembly 2018 CA $ 1,000 6.22.18 Tim Grayson for Assembly 2018 CA $ 1,000 6.22.18 Blanca Rubio Assembly 2018 CA $ 1,000 6.22.18 Friends of Kathy Byron VA $ 500 6.22.18 Friends of Kirk Cox VA $ 1,000 6.22.18 Kilgore for Delegate VA $ 500 6.22.18 Lindsey for Delegate VA $ 500 6.22.18 McDougle for Virginia VA $ 500 6.22.18 Stanley for Senate VA $ 1,000 6.22.18 Wagner -

Research Report Report Number 710, June 2012 Partisan Politics, Polarization, and Participation

Research Report Report Number 710, June 2012 Partisan Politics, Polarization, and Participation HIGHLIGHTS In the 2012 Utah Priorities Survey, respondents listed g In the 2012 Utah Priorities Survey, 52% of partisan politics as one of their top concerns for the respondents reported that they were concerned or very concerned about partisan politics, upcoming elections. This is significant not only because making it a top-ten issue for Utahns in this year’s elections. it was the first time this issue had been listed as a top-ten g The current Congress shows the highest historical level of polarization since the end of concern in this series of surveys, but also the first time it Reconstruction. was seen as a concern at all. There have been many reports g Since 1939, there has been a slow and steady decline in the number of moderates in the U.S. about the rise in partisanship and party polarization in Congress to a historic low for both chambers in 2011. national politics, and on the implications of this increase. g Utah’s voter turnout rate has been declining Partisanship can have important influences on voter turnout rates. Research indicates throughout the past several decades. Whereas Utah’s rate used to be well above the national that an increase in polarization “energizes the electorate” and increases voter turnout; average, it is now below average. high participation is indicative of a highly informed electorate where polarization is at its 1 g Research shows that the perception that an greatest. However, Utah’s voter participation rate has been declining for several decades. -

Az-Rep-20-2921

December 11, 2020 VIA EMAIL Representative Warren Petersen Arizona State Capitol Complex 1700 W Washington St., Rm. 208 Phoenix, AZ 85007 [email protected] Re: Public Records Request Dear Representative Petersen, Pursuant to the Arizona Public Records Law, A.R.S. §§ 39-121 et seq., American Oversight makes the following request for records. On November 30, 2020, members of the Arizona State Legislature met with President Trump’s personal lawyer, Rudy Giuliani, for an unofficial hearing in which participants aired unsubstantiated allegations regarding the integrity of the presidential election.1 Many of these same legislators have since called for a special session to directly appoint representatives to the Electoral College.2 American Oversight seeks records with the potential to shed light on whether or to what extent Arizona officials are acting at the behest of external political actors. Requested Records American Oversight requests that your office promptly produce the following records: All text message chains/conversations, or message chains/conversations on messaging applications similar in form to text messages (such as Signal, WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger, Twitter DMs, etc.), between (a) Speaker Warren Petersen or his Chief of Staff, Michael Hunter, and (b) any of the external parties listed below. 1 Ryan Randazzo & Maria Polletta, Arizona GOP Lawmakers Hold Meeting on Election Outcome with Trump Lawyer Rudy Giuliani, Ariz. Republic (updated Nov. 30, 2020, 9:02 PM), https://www.azcentral.com/story/news/politics/elections/2020/11/30/republican- lawmakers-arizona-hold-meeting-rudy-giuliani/6468171002/. 2 Maria Polletta, ‘Cowardly’ Say Some Arizona Republicans of Leaders Following Closure of Legislature, Ariz. -

20210106111314445 Gohmert V Pence Stay Appl Signed.Pdf

No. __A__________ In the Supreme Court of the United States LOUIE GOHMERT, TYLER BOWYER, NANCY COTTLE, JAKE HOFFMAN, ANTHONY KERN, JAMES R. LAMON, SAM MOORHEAD, ROBERT MONTGOMERY, LORAINE PELLEGRINO, GREG SAFSTEN, KELLI WARD AND MICHAEL WARD, Applicants, v. THE HONORABLE MICHAEL R. PENCE, VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES, IN HIS OFFICIAL CAPACITY. Respondent. EMERGENCY APPLICATION TO THE HONORABLE SAMUEL A. ALITO AS CIRCUIT JUSTICE FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT FOR ADMINISTRATIVE STAY AND INTERIM RELIEF PENDING RESOLUTION OF A TIMELY FILED PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI William L. Sessions Sidney Powell* Texas Bar No. 18041500 Texas Bar No. 16209700 SESSIONS & ASSOCIATES, PLLC SIDNEY POWELL, P.C. 14591 North Dallas Parkway, Suite 400 2911 Turtle Creek Blvd., Suite 1100 Dallas, TX 75254 Dallas, TX 72519 Tel: (214) 217-8855 Tel: (214) 628-9514 Fax: (214) 723-5346 Fax: (214) 628-9505 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Lawrence J. Joseph Howard Kleinhendler DC Bar #464777 NY Bar No. 2657120 LAW OFFICE OF LAWRENCE J. JOSEPH HOWARD KLEINHENDLER ESQUIRE 1250 Connecticut Av NW, Ste 700 369 Lexington Ave., 12th Floor Washington, DC 20036 New York, New York 10017 Tel: (202) 355-9452 Tel: (917) 793-1188 Fax: (202) 318-2254 Fax: (732) 901-0832 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Counsel for Applicants * Counsel of Record PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDING Applicants (plaintiffs-appellants below) are U.S. Rep. Louie Gohmert (TX-1), Tyler Bowyer, Nancy Cottle, Jake Hoffman, Anthony Kern, James R. Lamon, Sam Moorhead, Robert Montgomery, Loraine Pellegrino, Greg Safsten, Kelli Ward, and Michael Ward. Respondent (defendant-appellee below) is the Honorable Michael R. -

STATE of ARIZONA OFFICIAL CANVASS 2014 General Election

Report Date/Time: 12/01/2014 07:31 AM STATE OF ARIZONA OFFICIAL CANVASS Page Number 1 2014 General Election - November 4, 2014 Compiled and Issued by the Arizona Secretary of State Apache Cochise Coconino Gila Graham Greenlee La Paz Maricopa Mohave Navajo Pima Pinal Santa Cruz Yavapai Yuma TOTAL Total Eligible Registration 46,181 68,612 70,719 29,472 17,541 4,382 9,061 1,935,729 117,597 56,725 498,657 158,340 22,669 123,301 76,977 3,235,963 Total Ballots Cast 21,324 37,218 37,734 16,161 7,395 1,996 3,575 877,187 47,756 27,943 274,449 72,628 9,674 75,326 27,305 1,537,671 Total Voter Turnout Percent 46.17 54.24 53.36 54.84 42.16 45.55 39.45 45.32 40.61 49.26 55.04 45.87 42.68 61.09 35.47 47.52 PRECINCTS 45 49 71 39 22 8 11 724 73 61 248 102 24 45 44 1,566 U.S. REPRESENTATIVE IN CONGRESS - DISTRICT NO. 1 (DEM) Ann Kirkpatrick * 15,539 --- 23,035 3,165 2,367 925 --- 121 93 13,989 15,330 17,959 --- 4,868 --- 97,391 (REP) Andy Tobin 5,242 --- 13,561 2,357 4,748 960 --- 28 51 13,041 20,837 21,390 --- 5,508 --- 87,723 U.S. REPRESENTATIVE IN CONGRESS - DISTRICT NO. 2 (DEM) Ron Barber --- 14,682 --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- 94,861 --- --- --- --- 109,543 (NONE) Sampson U. Ramirez (Write-In) --- 2 --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- 54 --- --- --- --- 56 (REP) Sydney Dudikoff (Write-In) --- 5 --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- 43 --- --- --- --- 48 (REP) Martha McSally * --- 21,732 --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- 87,972 --- --- --- --- 109,704 U.S. -

2016 Legislative Scorecard

2016 LEGISLATIVE SCORECARD ARIZONA SENATE DISTRICT SENATOR PARTY SB1324 SB1474 SB1485 SB2599 SB1112 1 Steve Pierce R x x x 2 Andrea Dalessandro D 3 Olivia Cajero Bedford D NV 4 Lynne Pancrazi D NV 5 Susan Donahue R x x x x 6 Sylvia Allen R x x x x 7 Carlyle Begay R NV NV NV x 8 Barbara McGuire D 9 Steve Farley D 10 David Bradley D 11 Steve Smith R x x x x 12 Andy Biggs R x x x x 13 Don Shooter R x x x x 14 Gail Griffin R x x x x 15 Nancy Barto R x x x x 16 David C. Farnsworth R x x x x 17 Steve Yarbrough R x x x x 18 Jeff Dial R x x x x 19 Lupe Contreras D 20 Kimberly Yee R x x x x 21 Debbie Lesko R x x x x 22 Judy Burges R x x x x 23 John Kavanagh R x x x x 24 Katie Hobbs D 25 Bob Worsley R x x x x 26 Andrew C. Sherwood D 27 Catherine Miranda D x x x 28 Adam Driggs R x x x 29 Martin Quezada D 30 Robert Meza D SCORECARD GUIDE Voted WITH Planned Parenthood X Voted AGAINST Planned Parenthood NV Not Voting 2016 LEGISLATIVE SCORECARD ARIZONA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES DISTRICT REPRESENTATIVE PARTY SB1324 SB1474 SB1485 SB2599 SB1112 1 Noel W. Campbell R x x x x 1 Karen Fann R x x x x 2 J. Christopher Ackerley R x x x 2 Rosanna Gabaldón D 3 Sally Ann Gonzales D 3 Macario Saldate D 4 Charlene R.