August 31, 2016 Honorable Tom Vilsack, Secretary U.S. Department

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Petitioned the USDA

BEFORE THE UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE THE HUMANE SOCIETY OF THE UNITED STATES, WORLD WILDLIFE FUND, THE GLOBAL FEDERATION OF ANIMAL SANCTUARIES, THE INTERNATIONAL FUND FOR ANIMAL WELFARE, BORN FREE USA, THE FUND FOR ANIMALS, BIG CAT RESCUE, AND DETROIT ZOOLOGICAL SOCIETY PETITIONERS PETITION FOR RULEMAKING TO PROHIBIT PUBLIC CONTACT WITH BIG CATS, BEARS, AND NONHUMAN PRIMATES Anna Frostic (D.C. Bar No. 977732) Kimberly Ockene (D.C. Bar No. 461191) The Humane Society of the United States 2100 L Street NW Washington, DC 20037 [email protected] Amended January 7, 2013 (originally filed October 18, 2012) TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Notice of Petition…………………………………………………………………………...3 II. Introduction………………………………………………………………………………….8 III. Examples of Facilities that Offer Public Contact with Dangerous Wild Animals..9 IV. Legal Background and Authority to Amend Regulations…………………………..13 V. Current Handling Regulations Are Difficult to Enforce and Applied Inconsistently……………………………………………………………………………...19 VI. Public Handling of Big Cats, Bears, and Nonhuman Primates Undermines Animal Welfare, Public Safety, and Conservation and Must Be Prohibited…….23 A. Unmanaged Breeding………………………………………………24 B. Premature Mother-Infant Separation……………………………27 C. Excessive Handling of Young and Immature Animals………..34 D. Traveling Exhibition………………………………………………..35 E. Abusive Training, Declawing, and De-Fanging………………...38 F. Disease Transfer to Exhibited Animals……………………….…39 G. Risk of Physical Injury to Public During Handling……………42 H. Zoonotic Disease Transfer to Public……………………………...43 I. Risk of Injury to Public After Handling………………………….46 J. Conservation Impacts……………………………………………....49 VII. Proposed Amendments to Handling Regulations…………………………………….51 VIII. Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………….…54 IX. Expert Declarations…………………………………………………………………..…..56 X. Appendices….………………………………………………………..….See Enclosed Disc A. Evidence of Public Contact by Licensed Exhibitors B. -

January-March 2019 • Volume 63 Issue 1 TABLE OF

January-March 2019 • Volume 63 Issue 1 TABLE OF JANUARY-MARCH 2019 | VOLUME 63, ISSUE 1 contentscontents Features FCF Advocacy Fund for Engaging Hanka 5 Advisor Julia Wagner makes the case for federal representation. Lessons Learned from Experiencing a Tragedy 6 Dale Anderson and Wendy Debbas share 2020 wisdom and advice after deadly accident. Observations of an Aspiring Exhibitor 9 Bret Haughwort describes his journey to USDA- licensed exhibitor. Federal Judge Finds PETA Investigating 12 Technique Unlawful Duane Morris explains PETA audio was illegally obtained. What an Adventure in Belize! 14 Debi Willoughby takes readers to Belize for wild cat research. King Richard’s Faire Features Felines from 20 Great Cats World Park Lynn Culver reviews this festive outdoor performance. How to Deal with the Days that Follow a Fatal 23 Accident Support from friends, associates, and the community helped Hannah Fullmer recover. Joe Exotic Charged with Murder for Hire, 25 Taking and Sales of Endangered Species, and False Labeling Lynn Culver describes crimes alleged in federal indictment of former zoo owner. 99 66 1111 Feline Conservation Federation Volume 63, Issue 1 • Jan.-March 2019 JOIN THE FCF IN ITS CONSERVATION EFFORTS - WWW.FELINECONSERVATION.ORG The FCF supports conservation of wild felids by advocating for qualified individuals to own and to pursue hus- bandry of wild felines, providing expertise and material support to ensure the continued welfare and viability of these populations, contributing to research, and funding protection programs that benefit felids living in nature. Send $35 annual dues ($40 Canada, $50 international) to FCF, 141 Polk Road 664, Mena, AR 71953. -

Virginia Law Weekly Virginia Law Weekly

VIRGINIA LAW WEEKLY 2017, 2018, & 2019 ABA Law Student Division Best Newspaper Award-Winner A Look Pending Changes to Bar Exam.................................3 Love in the Time of Corona......................................4 Inside: Lesson from a Falling Sky......... ..............................5 Wednesday, 8 April 2020 The Newspaper of the University of Virginia School of Law Since 1948 Volume 72, Number 23 Joint Statement around north from Dean grounds Goluboff and Dean Goluboff Hosts Skardon ’22 Hearts out to ev- Coffee Chat in eryone in social quarantine. Hang in On Monday, April 6, at 9:09 there, folks! p.m., Dean Risa Goluboff and Wake of Controversy Frannie Skardon ’22 released a Thumbs down joint statement to the Law Week- to the @UVALaw ly in response to our request for Twitter account further comment from the dean screenshotting the regarding Michael Berdan ’22’s Law Weekly’s work instead article recapping the Coffee with of linking to it. Like its peers, the Dean event. At this event, stu- the New York Times and dents had vigorously discussed the Washington Post, the the controversy surrounding Law Weekly values the page Ms. Skardon’s appeal to remain views that pour in when an a full-time student. The joint administration mismanages statement is reproduced below a public crisis. without edits. The Law Weekly does not necessarily endorse the Thumbs up to content or viewpoint herein pub- ANG’s newfound lished. efficiency at class- Statement begins: work. ANG only We are reaching out jointly to took three days to listen to express how glad we both are a one hour recorded lecture. -

The Prospector, April 7, 2020

University of Texas at El Paso ScholarWorks@UTEP The Prospector Special Collections Department 4-7-2020 The Prospector, April 7, 2020 UTEP Student Publications Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.utep.edu/prospector Part of the Journalism Studies Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation UTEP Student Publications, "The Prospector, April 7, 2020" (2020). The Prospector. 375. https://scholarworks.utep.edu/prospector/375 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections Department at ScholarWorks@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Prospector by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. News Entertainment Sports Pandemic: Students return from abroad, page 3 ‘Tiger King’ a brilliant docuseries, page 5 NCAA grants extra year, page 7 VOL. 105, NO. 23 APRIL 7, 2020 THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT EL PASO WWW.THEPROSPECTORDAILY.COM UTEP names new provost Isaiah Ramirez UTEP fi rst announced its search for a new provost in October The Prospector 2019 with the search committee being led by Vice President of Student Aff airs Gary Edens. University of Texas at El Paso President Heather Wilson an- Th e position of a provost is a highly touted position at a uni- nounced John S. Wiebe will be promoted to become the univer- versity, as it oversees all areas related to university curriculum sity’s president for academic aff airs and provost aft er holding the and faculty appointments, as well as being the chief academic interim position since January of last year. -

Crystal River Energy Complex

Project1:Layout 1 6/10/2014 1:13 PM Page 1 Religion: Greek food festival adjusts its plan for 2020 /A14 SATURDAY TODAY CITRUSCOUNTY & next morning HIGH 88 Partly sunny with LOW scattered storms. 72 PAGE A4 www.chronicleonline.com OCTOBER 10, 2020 Florida’s Best Community Newspaper Serving Florida’s Best Community 50¢ VOL. 126 ISSUE 2 NEWS BRIEFS Voter registration won’t be extended Walker shared in the exasperation of voter Citrus County Judge denies request, rips Florida’s election issues advocacy groups even as he ruled against them, peppering his opinion with sharply COVID-19 update BObbY CAINA CALVAN taking part in November’s presidential worded criticisms of the state. Sixteen new positive AND FREIDA FRISARO election. “In so ruling, this Court notes that every cases were reported in Associated Press In a 29-page ruling on Friday morning, U.S. man who has stepped foot on the Moon Citrus County since the District Court Judge Mark E. Walker said his launched from the Kennedy Space Center, latest FDOH update. Two TALLAHASSEE — A federal judge has de- decision was “an incredibly close call” but in Florida. Yet, Florida has failed to figure out new hospitalizations were nied a motion to extend voter registration in added that “the state’s interest in preventing how to run an election properly — a Florida even though a computer meltdown on chaos in its already precarious — and peren- task simpler than rocket science,” the judge reported; three new deaths the final day of registration might have pre- nially chaotic — election outweighs the sub- wrote. -

Murder, Intrigue, and the FLSA: What Tiger King Can Teach You About Wage and Hour Compliance Insights 5.29.20

Murder, Intrigue, And The FLSA: What Tiger King Can Teach You About Wage And Hour Compliance Insights 5.29.20 As the COVID-19 pandemic swept over the world, an unlikely phenomenon swept the United States. While new terms like “social distancing” and “essential employees” suddenly became part of the common lexicon, a surprising phrase also emerged: “Tiger King.” Released on Netflix on March 20, “Tiger King: Murder, Mayhem and Madness” is a true-crime documentary detailing the life of zookeeper, Joe Exotic. This seven-episode series took viewers on a wild ride through the surprisingly small world of big cat collectors and conservationists. Each episode presented a more outrageous addition to the story that spawned multiple jaw-dropping moments and some of the greatest memes of 2020. At the heart of Tiger King was the explosive and dangerous rivalry between Joe Exotic and his archnemesis, Carol Baskin. The level of vitriol and disdain shared between Carol and Joe made for great television and a jury trial. Another jaw dropping moment from Tiger King, at least for those of us in the labor and employment law world, was the revelation that the individuals caring for these big cats were seemingly not compensated in line with the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) – if they were compensated at all. Each of the compensation schemes featured warrant a closer inspection, as incorrect use of these methods of compensation could subject an employer to liability. The FLSA: Minimum Wage And Overtime Requirements The FLSA requires that non-exempt employees are to be paid a minimum wage rate and “time-and- a-half” overtime pay when people work over forty hours a week. -

June 3, Issue.Qxp April 6, 2013

Weekly Call Birmingham Mes senger Southern Labor Review Alabama Legal Advertiser PUBLISHED WEEKLY SINCE 1918 NOW SEMI-WEEKLY Subscription/Advertising Information BIRMINGHAM (205) 252-3672 BESSEMER (205) 425-0301 The ALABAMA MESSENGER is a semi-weekly newspaper dedicated to serving the People, Courts, Attorneys, and Businesses of Jefferson County, as an efficient and qualified medium for all legal publications. Volume 100 Number 44 (25 Cents) Saturday, June 3, 2017 ADVERTISEMENT FOR A/E NOTICE TO BIDDERS CONTINUATION OF NOTICE OF MORTGAGE FORECLOSURE SALE Case No. 17BHM01279 NOTICE OF SALE OF REQUEST FOR STATEMENT OF Sealed Bid Proposals will be MORTGAGE FORECLOSURE SALE Default having been made in the NOTICE TO CREDITORS ABANDONED MOTOR VEHICLE QUALIFICATIONS received by the Environmental Default having been made under the payment of the indebtedness secured In the Probate Court of Jefferson In accordance with Section 32-13-1, DATE May 10, 2017 Services Department, Jefferson terms of that certain Mortgage and by that certain mortgage executed by County, Alabama Code of Alabama, 1975, notice is FROM County, Alabama, in Room 270, Security Agreement dated August 21, Linda Readus, an unmarried woman, In the matter of the Estate of: hereby given to the owners, lienhold- Jefferson County Commission Commission Chambers, Courthouse, 2015 (the “Mortgage”), executed by originally in favor of Mortgage DANNY MACK POUNDS, Deceased ers and other interested parties, that Alabama General Services Department, Room 1 Birmingham, Alabama, until 2:00 P.M. East Thomas Properties, LLC, an Electronic Registration Systems, Inc., Letters of Administration upon the the following described abandoned 716 Richard Arrington Jr. -

Contents Lake Highland Adapts Traditions in * * * ◊ Reopening the U.S

Volume 20, Issue 7 Lake Highland Preparatory School, 901 Highland Avenue, Orlando, Florida, 32803 May 2020 Contents Lake Highland Adapts Traditions in * * * ◊ Reopening the U.S. One Step at a Time... By Ahmed Bilal Pg. 2 Troubling Times By Christopher Raymond ◊ Coronavirus and How It Has Transformed thing else that is my brand Our Society... By Noor Sattar Pg. 8-9 Kenny Rogers’ except for mocktails), it gambler, in the song of felt as though the world the same name, may have, as we knew it was closing, ◊ Balancing Containment* * and * Freedom “Made a life out of readin’ but no change threatened people’s faces [and] know- Globally... By Sarah Finfrock Pg. 3 to disrupt our daily lives in’ what the cards were more than the transition of by the way they held their our school to on-line learn- ◊ Online Boredom Busters Bring Benefits... eyes,” but I unfortunately ing. We would no longer doubt that the same gam- By Camryn Curry Pg. 4 be going to see each oth- bler would hold identical er every day, making us power in the present. As miss out on some crucial ◊ Tiger King Whimpers its Conservation we continue to navigate human contact, but it was Message... By Maddy Russell Pg. 5 forward, there have been an unfortunate necessity in a wide variety of efforts to order to maintain our safe- ensure that Lake Highland (Above) Seniors saw friends, got their caps and gowns, and made countless memories at this year’s Senior Car ty, which is the number one ◊ Lake Highland Students Spark is able to continue on in Parade. -

THE Weekly Newspaper

THE TM 911 Franklin Street Weekly Newspaper Michigan City, IN 46360 Volume 36, Number 14 Thursday, April 9, 2020 THE Page 2 April 9, 2020 THE 911 Franklin Street • Michigan City, IN 46360 219/879-0088 About the Cover e-mail: News/Articles - [email protected] email: Classifieds - [email protected] For our Easter edition cover, we asked talented http://www.thebeacher.com/ local photographer Amanda Tonagel to produce PRINTE ITH Published and Printed by something for us, and what she came up with T T A S A THE BEACHER BUSINESS PRINTERS is absolutely charming. The young girl in the picture? None other than her daughter, Greta. Delivered weekly, free of charge to Birch Tree Farms, Duneland Beach, Grand Beach, Hidden Shores, Long Beach, Michiana Shores, Michiana MI and Shoreland Hills. The Beacher is Thanks to Amanda for sharing her wonderful also delivered to public places in Michigan City, New Buffalo, LaPorte and Sheridan Beach. talent with us! Spirit of Radio by Andrew Tallackson A few years back, John Landeck- er was promoting his book Records Truly Is My Middle Name with a live broadcast at Galveston Steak- house. Playing a few tunes, signing copies of the book, he’d invited his Chicago publisher, along with a few others in the radio industry, to at- tend. The freedom the legendary radio personality had, to say and play whatever he desired, fl oored his pals “They could not believe it,” Lan- decker recalled. “They said, ‘You play whatever you want from your computer? You have 10 minutes with one of your sponsors? I said, ‘Welcome to Michigan City.’ They couldn’t believe it. -

Cert No Name Doing Business As Address City Zip 1 Cust No

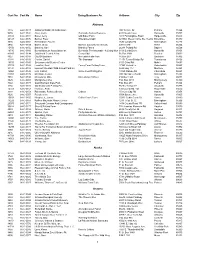

Cust No Cert No Name Doing Business As Address City Zip Alabama 3316 64-C-0117 Alabama Wildlife Rehabilitation 100 Terrace Dr Pelham 35124 9655 64-C-0141 Allen, Keith Huntsville Nature Preserve 431 Clouds Cove Huntsville 35803 33483 64-C-0181 Baker, Jerry Old Baker Farm 1041 Farmingdale Road Harpersville 35078 44128 64-C-0196 Barber, Peter Enterprise Magic 621 Boll Weevil Circle Ste 16-202 Enterprise 36330 3036 64-C-0001 Birmingham Zoo Inc 2630 Cahaba Rd Birmingham 35223 2994 64-C-0109 Blazer, Brian Blazers Educational Animals 230 Cr 880 Heflin 36264 15456 64-C-0156 Brantley, Karl Brantley Farms 26214 Pollard Rd Daphne 36526 16710 64-C-0160 Burritt Museum Association Inc Burritt On The Mountain - A Living Mus 3101 Burritt Drive Huntsville 35801 42687 64-C-0194 Cdd North Central Al Inc Camp Cdd Po Box 2091 Decatur 35602 3027 64-C-0008 City Of Gadsden Noccalula Falls Park Po Box 267 Gadsden 35902 41384 64-C-0193 Combs, Daniel The Barnyard 11453 Turner Bridge Rd Tuscaloosa 35406 19791 64-C-0165 Environmental Studies Center 6101 Girby Rd Mobile 36693 37785 64-C-0188 Lassitter, Scott Funny Farm Petting Farm 17347 Krchak Ln Robertsdale 36567 33134 64-C-0182 Lookout Mountain Wild Animal Park Inc 3593 Hwy 117 Mentone 35964 12960 64-C-0148 Lott, Carlton Uncle Joes Rolling Zoo 13125 Malone Rd Chunchula 36521 22951 64-C-0176 Mc Wane Center 200 19th Street North Birmingham 35203 7051 64-C-0185 Mcclelland, Mike Mcclellands Critters P O Box 1340 Troy 36081 3025 64-C-0003 Montgomery Zoo P.O. -

Report on Legislation by the Animal Law Committee H.R

REPORT ON LEGISLATION BY THE ANIMAL LAW COMMITTEE H.R. 263 Rep. Quigley S. 1210 Sen. Blumenthal AN ACT To amend the Lacey Act Amendments of 1981 to clarify provisions enacted by the Captive Wildlife Safety Act, to further the conservation of certain wildlife species, and for other purposes. The Big Cat Public Safety Act THIS LEGISLATION IS SUPPORTED I. SUMMARY OF THE PROPOSED LEGISLATION The bill would prohibit private ownership of tigers, lions, leopards, cheetahs, jaguars, cougars (a group popularly referred to as “big cats”) or any hybrid of these species.1 Current owners are grandfathered in and required to register their animals with the government. The proposed legislation includes exemptions for universities, sanctuaries, and entities with a Class C USDA license (public exhibition license). The bill also restricts direct contact between the public and big cats (currently provided by roadside and petting zoos). A prior version of the bill was originally introduced as H.R. 1380 by Rep. Quigley in 2017 and later reintroduced in 2019.2 H.R. 1380 passed in the House by a vote of 272 to 114 in December 2020.3 The Senate failed to pass the reciprocal legislation to H.R. 1380, S. 2561 (which was introduced in the Senate by Sen. Blumenthal) before the 116th legislative session ended.4 As such, Rep. Quigley introduced the bill in the House as H.R. 263 in January 2021.5 A bipartisan group of senators, consisting of Senators Blumenthal (D-Conn.), Burr (R-N.C.), Carper (D-Del.) and Collins (R-Me), introduced the bill in the Senate as S.1210 on April 19, 2021.6 The Big Cat Public Safety Act would amend the Lacey Act Amendments of 19817 to clarify provisions enacted by the Captive Wildlife Safety Act.8 To date, there are 195 lawmakers in the House of Representatives, both Democrats and Republicans, who are cosponsoring the bill. -

Tiger Kingdom: Coronavirus, Conspiracy, and US Popular Culture

DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/Z3WMY Tiger Kingdom: Coronavirus, Conspiracy, and US Popular Culture Kyle A. Hammonds, University of Oklahoma Humans have invented all sorts of Murder, Mayhem, and Madness. The series techniques for coping with uncertainty. As was released in March 2020, just as many the United States becomes more institutions began closing in response to the postmodern, perspectival, and COVID-19 pandemic. These closures were individualistic, the need for psychological unprecedented to many people and came to structures to process uncertainty increases. represent a frightening source of uncertainty. One of the most prevalent coping Tiger King – conspiratorial without posing mechanisms for uncertainty in the United immediate danger and chalked full of States right now is conspiracy theory. characters that folks could love to hate – was Indulging conspiracy theories both enables just the escapism people wanted during the ways of explaining otherwise mysterious onset of coronavirus. This essay will note a events and maintains a sense of cynicism few of themes from the show which may toward others that is typical of postmodern have contributed to its overall popularity, society. In other words, conspiracy theories putting Tiger King in context of the present grasp at certainty without letting go of the historical moment and its relationship to characteristic distrust of others that is so narrative strands in broader US popular popular in the present time. Conspiratorial culture. modes of thinking have become pervasive in US popular culture. It is no coincidence that Coronavirus and Popular Culture spy movies, [neo]noir, and horror have seen a resurgence since the array of cultural shifts The questions of how and why Tiger in the ‘60s and ‘70s.