Franz Marc, Mary Oliver and the Ekphrastic Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Franz Marc Animals Fine Art Pages

Playing Weasels Painted by: Franz Marc When: 1909 Style: Expressionism Interesting Fact: Franz Marc was a German painter and printmaker that lived from 1880 to 1916. He studied in Munich and in France. Franz Marc Fine Art Pages by EnrichmentStudies.com Siberian Sheepdogs Painted by: Franz Marc When: 1910 Materials and Technique: oil on canvas Style: Post-Impressionism Interesting Fact: While serving in the German military in World War I, Marc painted tarp covers in various artistic styles, ranging “from Manet to Kandinsky” in hopes of hiding artillery. Franz Marc Fine Art Pages by EnrichmentStudies.com Blue Horse I Painted by: Franz Marc When: 1911 Materials and Technique: oil on canvas Style: Expressionism Franz Marc Fine Art Pages by EnrichmentStudies.com Deer in the Snow Painted by: Franz Marc When: 1911 Materials and Technique: oil on canvas Style: Expressionism Franz Marc Fine Art Pages by EnrichmentStudies.com Donkey Frieze Painted by: Franz Marc When: 1911 Materials and Technique: oil on canvas Style: Expressionism Interesting Fact: Most of Marc’s work portrays animals in a very stark way, using bold colors. His style caught the attention of the art world. Franz Marc Fine Art Pages by EnrichmentStudies.com Monkey Frieze Painted by: Franz Marc When: 1911 Materials and Technique: oil on canvas Interesting Fact: A “frieze” is a wide horizontal painting or other decoration, often displayed on a wall near the ceiling. Franz Marc Fine Art Pages by EnrichmentStudies.com Resting Cows Painted by: Franz Marc When: 1911 Materials and Technique: oil on canvas Style: Expressionism Franz Marc Fine Art Pages by EnrichmentStudies.com The Yellow Cow Painted by: Franz Marc When: 1911 Materials and Technique: oil on canvas Style: Expressionism Interesting Fact: The style of Expressionism was a modern form of art that began in the early 1900s. -

Franz Marc Became World Famous for His Expressionist Animal Paintings; No Other Body of Work Has Been So Frequently Reproduced As That of This Munich Artist

The 100th Anniversary of Franz Marc’s Death “Unnoticed trails of life” Blue horses, yellow cows, red deer – Franz Marc became world famous for his Expressionist animal paintings; no other body of work has been so frequently reproduced as that of this Munich artist. One hundred years after his death, biographies and exhibitions afford significant and sometimes previously unknown insights into Marc’s life and work. Feed 1: “How many times have I longed to roam over these heights, plangently playing on the dark violin of nature; oh, why has fate shut me out from this art? But I would die from this longing, most assuredly, just as from the yearning of love had it never been fulfilled; or from painting – did I not myself paint.” Speaker: Franz Marc in 1906. The twenty-six-year old artist is at home, at the foot of the Bavarian Alps, to paint animals. He is still searching for his own style. Again and again Marc is plagued by his broken off art studies, the few number of his works, financial difficulties. He is searching for a religious affiliation, initially to Christianity and later to Buddhism. His inner conflict, the tendency to melancholy, fear and apprehension – all this is reflected in his life and work. Feed 2: “And because of this distress Marc sought contact with people. We can see this in his early relationships with women, but with men and colleagues he was also extraordinarily companionable, very “team-oriented”,” Speaker: as the journalist and Marc expert Brigitte Roßbeck writes. In 1911 Marc meets Vassily Kandinsky. -

The Tower of Blue Horses by Bernhard Jaumann

Sample translation pp. 7-32 and pp. 57-59 The Tower of Blue Horses by Bernhard Jaumann Crime novel Translated by John Reddick © 2019, Verlag Galiani Berlin Publication: September February 2019 (Flexcover) 329 pages World rights with: Verlag Kiepenheuer & Witsch GmbH & Co. KG Iris Brandt [email protected] Aleksandra Erakovic: [email protected] Sample translation Bernhard Jaumann „The Tower of Blue Horses“ Berchtesgaden Region 5 May 1945 Ludwig Raithmaier wouldn’t have minded being someone else rather than who he actually was - but he wasn’t sure whether he would have been any good as a werewolf. ‘What exactly are werewolves?’ he asked. Xaver had only told him what he had heard on the radio: that the werewolves would help them to achieve the great Final Victory; that between them they and the Führer’s wonder weapons would turn the tables on their enemies. The Führer may have died a hero’s death on the battlefield, but the German Volk would never perish: they would barricade themselves into their impregnable Alpine fortress and resist each and every onslaught until the Americans and Russians had completely wiped each other out. Xaver stared at the gaping black hole of the railway tunnel some one hundred metres ahead of them, and said, ‘Werewolves are men who turn into ravening wolves in the depths of the night.’ It wasn’t night yet, and even though the sun had already disappeared behind the mountains the light was fading only slowly. Ludwig gazed up at the mountain peaks, where jagged clouds were racing eastwards as if heading for somewhere in particular. -

“The Flow of Blood in Nature” Franz Marc's Animal Theory

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2013 “The Flow of Blood in Nature” Franz Marc’s Animal Theory Morgan Rinehart Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/578 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Morgan Chelsea Rinehart 2013 All Rights Reserved ! “The Flow of Blood in Nature” Franz Marc’s Animal Theory A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at Virginia Commonwealth University. by Morgan Chelsea Rinehart B.A. Art History Old Dominion University, May 2011 Director: Dr. Kathleen Chapman, Assistant Professor, Department of Art History Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia November 18, 2013! ! ! ii Acknowledgment I would like to acknowledge the assistance of Dr. Kathleen Chapman. Her knowledge and guidance were invaluable to the success of this project, and I am very grateful to her for her time and expertise. I would also like to thank the members of my thesis committee, Dr. Eric Garberson and Dr. Janna Israel, for sharing their time with me and for their considerable insight and enthusiasm for this project. I am sincerely thankful for the generosity of the Robert Gore Rifkind Foundation for sponsoring my research at the Rifkind Center for German Expressionist Art and to the staff of the Rifkind Center for enabling me to draw on their rich collections of prints and rare texts. -

Franz Marc Free Ebook

FREEFRANZ MARC EBOOK Victoria Charles | 256 pages | 28 Feb 2014 | Parkstone Press Ltd | 9781781602546 | English | London, United Kingdom Franz Marc | A Master Class in German Expressionism | Art & Home Franz Marc was one of the key figures of German Expressionism. Marc was born in in Munich, Germany and began his painting career at age 20 when he studied at the Franz Marc of Fine Arts in Munich. During these studies, he traveled frequently to Paris where he discovered an affinity for the work of Vincent van Gogh, and influence you can clearly see Franz Marc his paintings. As a founding member of Der Blaue Reiter The Blue Riderhe created a journal that became synonymous with the circle of German Expressionist artists including Macke, Wassily Kandinsky, and others who split off from Neue Kunstlervereinigung Munchen, an avant-garde exhibiting society founded in Munich in the early s. Today we are searching for things in nature that are hidden behind the veil of appearance… We look for and paint this inner, spiritual side of nature. Shortly after beginning his career as an artist, the World erupted in War and Franz Marc was drafted Franz Marc the German Army. Franz Marc Marc was on that list, before the orders to remove him from active duty could reach him, he was struck and killed by a shell during the Battle of Verdun in Tragedy continued to strike the young artist, even after he died. Some of these artworks remained hidden for decades, others were never recovered. Franz Marc had a fascination with painting animals, and that showed in his mature artwork. -

Franz Marc Study Guide

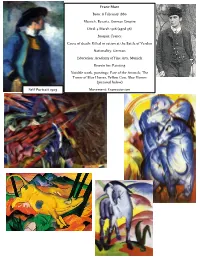

Franz Marc Born: 8 February 1880 Munich, Bavaria, German Empire Died: 4 March 1916 (aged 36) Braquis, France Cause of death: Killed in action at the Battle of Verdun Nationality: German Education: Academy of Fine Arts, Munich Known for: Painting Notable work, paintings: Fate of the Animals, The Tower of Blue Horses, Yellow Cow, Blue Horses (pictured below) Self Portrait 1905 Movement: Expressionism Book List: 13 Artists Children Should Know by Angela Wenzel Franz Marc by Susanna Partsch FRANZ MARC: Life and Work by Claus Pese Websites: Franz Marc - Wikipedia Franz Marc - paintings, biography, quotes of Franz Marc Franz Marc Paintings Fate of the Animals by Franz Marc (artclasscurator.com) Activities: 1. Paint or use construction paper to make colorful animal artwork 2. Watch this Youtube video - (33) Learn how to draw A FRANZ MARC INSPIRED BROWN BEAR : STEP BY STEP GUIDE! (Age 5 +) - YouTube 3. Handprint Blue Horse 4. Eric Carle (author of Brown Bear Brown Bear What do You See? and many others) pays homage to Franz Marc with his book “The Artist Who Painted the Blue Horse.” Read the book. (find the Amazon link for the book on my website) Art Appreciation – Franz Marc Thank you for downloading the Pablo Franz Marc Study Guide. All of the curriculum on my website is intended for home use. There are Amazon Affiliated links on my site of any books or supplies I mention. If you decide to buy any of them, please use the links on my website. I take no credit for most of the images I use. -

Fauvism and German Expressionism

Avant-garde - French for vanguard (The foremost or leading position in an army or in a trend or movement.). Artworks and artists which stand in the forefront of a movement or of new ideas, often in opposition to established ideas and traditions; art that's ahead of its time, innovative, experimental. Matisse and Fauvism The leader of the Fauves was Henri Matisse (1869-1954) French painter, sculptor, and graphic artist. His varied subjects comprised landscape, still life, portraiture, domestic and studio interiors, and particularly focused on the female figure. Henri Matisse. Self- Portrait in a Striped T- Shirt. 1906. Fauvism: c. 1905 – 1908 Fauvism: Movement in French painting characterized by the use of intensely vivid colors, often applied unmixed from commercially produced tubes of paint in broad flat areas, by a spontaneity and even roughness of execution. Some works drew from the art of Africa, Pre-Columbian America and Oceania. Matisse, Woman with the Hat, 1905. SF MOMA The Fauves found their name when a critic pointed to a renaissance-like sculpture in the middle of the same gallery as their exhibition and exclaimed 'Donatello au milieu des fauves!' ('Donatello among the wild beasts!'). Andre Derain, The Dance Henri Matisse, The Joy of Donatello, 1906. Oil on canvas, 6’ 7/8” x Life (Le Joie de vivre), David, 1430, 6’ 10 1/4”. 1905-06, oil on canvas bronze “What I dream of is an art of balance, of purity- and serenity, devoid of troubling or depressing subject- matter, an art which could be for every mental worker….. a soothing, calming influence on the mind, something like a good armchair…” --From "Notes of a Painter“ by Matisse Henri Matisse, The Joy of Life (Le Joie de vivre), 1905-06, oil on canvas Renaissance - Giovanni Bellini, The Feast of The Gods, 1514 Cezanne, Large Bathers (unfinished), 1899-1906 Henri Matisse, The Joy of Life, 1905-06 Influences of African Art: • In 1906 Matisse Derain and Vlamick began to collect art objects from Africa which they had first seen in ethnographic museums and to adapt their forms into their art.