The Myth of "Moonrise Kingdom": a Children's Tale

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EE British Academy Film Awards Sunday 8 February 2015

EE British Academy Film Awards Sunday 8 February 2015 Previous Nominations and Wins in EE British Academy Film Awards only. Includes this year’s nominations. Wins in bold. Leading Actor Benedict Cumberbatch 1 nomination Leading Actor in 2015: The Imitation Game Eddie Redmayne 1 nomination Leading Actor in 2015: The Theory of Everything Orange Wednesdays Rising Star Award Nominee in 2012 Jake Gyllenhaal 2 nominations / 1 win Supporting Actor in 2006: Brokeback Mountain Leading Actor in 2015: Nightcrawler Michael Keaton 1 nomination Leading Actor in 2015: Birdman Ralph Fiennes 6 nominations / 1 win Supporting Actor in 1994: Schindler’s List Leading Actor in 1997: The English Patient Leading Actor in 2000: The End of The Affair Leading Actor in 2006: The Constant Gardener Outstanding Debut by a British Writer, Director or Producer in 2012: Coriolanus (as Director) Leading Actor in 2015: The Grand Budapest Hotel Leading Actress Amy Adams 5 nominations Supporting Actress in 2009: Doubt Supporting Actress in 2011: The Fighter Supporting Actress in 2013: The Master Leading Actress in 2014: American Hustle Leading Actress in 2015: Big Eyes Felicity Jones 1 nomination Leading Actress in 2015: The Theory of Everything Julianne Moore 4 nominations Leading Actress in 2000: The End of the Affair Supporting Actress in 2003: The Hours Leading Actress in 2011: The Kids are All Right Leading Actress in 2015: Still Alice Reese Witherspoon 2 nominations / 1 win Leading Actress in 2006: Walk the Line Leading Actress in 2015: Wild Rosamund Pike 1 nomination Leading Actress in 2015: Gone Girl Supporting Actor Edward Norton 2 nominations Supporting Actor in 1997: Primal Fear Supporting Actor in 2015: Birdman Ethan Hawke 1 nomination Supporting Actor in 2015: Boyhood J. -

Isle of Dogs (Dir

Nick Davis Film Discussion Group April 2018 Isle of Dogs (dir. Wes Anderson, 2018) Dog Cast Chief (the main dog): Bryan Cranston: One of the only non-Anderson vets in the U.S. cast Rex (a semi-leader): Edward Norton: Moonrise Kingdom (12); Grand Budapest Hotel (14) Duke (gossip fan): Jeff Goldblum: fantastic in underseen British gem Le Week-end (13) Boss (mascot jersey): Bill Murray: rebooted career by starring in Anderson’s Rushmore (98) King (in their crew): Bob Balaban: hilarious in a very different dog movie, Best in Show (00) Spots (Atari’s dog): Liev Schreiber: oft-cast as dour antiheroes: Ray Donovan (13-18), etc. Nutmeg (Chief’s crush): Scarlett Johansson: controversially appeared in Ghost in the Shell (17) Jupiter (wise hermit): F. Murray Abraham: won Best Actor Oscar as Salieri in Amadeus (84) Oracle (TV prophet): Tilda Swinton: an Anderson regular since Moonrise Kingdom (12) Gondo (lead “cannibal”): Harvey Keitel: untrue rumors of cruelty a riff on his usual typecasting Peppermint (Spots’ girl): Kara Hayward: the young female co-lead of Moonrise Kingdom (12) Human Cast Atari (young pilot): Koyu Rankin: Japanese-Scottish-Canadian, in his first feature film Kobayashi (evil mayor): Kunichi Nomura: enlisted as Japanese cultural consultant, then cast Prof. Watanabe: Akiro Ito: actor/dancer; briefly appears as translator in Birdman (14) Interpreter Nelson: Frances McDormand: another veteran of Moonrise Kingdom (12) Tracy (U.S. student): Greta Gerwig: the Oscar-nominated writer-director of Lady Bird (17) Yoko Ono (scientist): Yoko Ono: 83-year-old avant-garde musician and performance artist Narrator: Courtney B. -

Moonrise Kingdom"

"Moonrise Kingdom" Screenplay by Wes Anderson and Roman Coppola May 1, 2011 INT. BISHOP’S HOUSE. DAY A landing at the top of a crooked, wooden staircase. There is a threadbare, braided rug on the floor. There is a long, wide corridor decorated with faded paintings of sailboats and battleships. The wallpapers are sun-bleached and peeling at the corners except for a few newly-hung strips which are clean and bright. A small easel sits stored in the corner. Outside, a hard rain falls, drumming the roof and rattling the gutters. A ten-year-old boy in pajamas comes up the steps carefully eating a bowl of cereal as he walks. He is Lionel. Lionel slides open the door to a low cabinet under the window. He takes out a portable record player, puts a disc on the turntable, and sets the needle into the spinning groove. A child’s voice says over the speaker: RECORD PLAYER (V.O.) In order to show you how a big symphony orchestra is put together, Benjamin Britten has written a big piece of music, which is made up of smaller pieces that show you all the separate parts of the orchestra. As Lionel listens, three other children wander out of their bedrooms and down to the landing. The first is an eight-year-old boy in a bathrobe. He is Murray. The second is a nine-year-old boy in white boxer shorts and a white undershirt. He is Rudy. The third is a twelve-year-old girl in a cardigan sweater with knee-high socks and brightly polished, patent-leather shoes. -

Bruce Jackson & Diane Christian Video Introduction to This Week's Film

April 28, 2020 (XL:13) Wes Anderson: ISLE OF DOGS (2018, 101m) Spelling and Style—use of italics, quotation marks or nothing at all for titles, e.g.—follows the form of the sources. Bruce Jackson & Diane Christian video introduction to this week’s film (with occasional not-very-cooperative participation from their dog, Willow) Click here to find the film online. (UB students received instructions how to view the film through UB’s library services.) Videos: Wes Anderson and Frederick Wiseman in a fascinating Skype conversation about how they do their work (Zipporah Films, 21:18) The film was nominated for Oscars for Best Animated Feature and Best Original Score at the 2019 Academy Isle of Dogs Voice Actors and Characters (8:05) Awards. The making of Isle of Dogs (9:30) CAST Starting with The Royal Tenenbaums in 2001, Wes Isle of Dogs: Discover how the puppets were made Anderson has become a master of directing high- (4:31) profile ensemble casts. Isle of Dogs is no exception. Led by Bryan Cranston (of Breaking Bad fame, as Weather and Elements (3:18) well as Malcolm in the Middle and Seinfeld), voicing Chief, the cast, who have appeared in many Anderson DIRECTOR Wes Anderson films, includes: Oscar nominee Edward Norton WRITING Wes Anderson wrote the screenplay based (Primal Fear, 1996, American History X, 1998, Fight on a story he developed with Roman Coppola, Club, 1999, The Illusionist, 2006, Birdman, 2014); Kunichi Nomura, and Jason Schwartzman. Bob Balaban (Midnight Cowboy, 1969, Close PRODUCERS Wes Anderson, Jeremy Dawson, Encounters -

American Film Festival 13– 18.11.2012 Wrocław

american film festival 13– 18.11.2012 wrocław 3 www.americanfilmfestival.pl program kino | nowe horyzonty kazimierza wielkiego 19a-21, 50–077 wrocław Życie na szali / Bigger Than Life Dziewczyna w masce lisicy / White Fox Mask Jak przetrwać epidemię / How to Survive a Plague Bernie reż. Nicholas Ray reż. Ricky Shane Reid reż. David France reż. Richard Linklater 19:0020:0021:00 22:0023:00 Redakcja dodatku: Urszula Śniegowska american film festival NH1 19:00 Gala otwarcia – Kochankowie z Księżyca. Korekta: Agnieszka Rasmus-Zgorzelska Moonrise Kingdom Projekt graficzny i skład: Homework W. Anderson, 94’ Autorzy: Kuba Armata (ka), Anna Bielak (ab), NH6 20:00 Dracula Bartek Czartoryski (bc), Piotr Czerkawski (pc), – .. T. Browning, 75’ Szymon Holcman (sh), Błażej Hrapkowicz (bh), Kaja Klimek (kk), Grzegorz Kurek (gk), NH7 20:00 Na własne ryzyko Joanna Ostrowska (jo), Joanna Ozdobińska (ao), Safety Not Guaranteed Karolina Pasternak (kp), Rafał Pawłowski (rp), wrocław, poland C. Trevorrow, 86’ Marcin Pieńkowski (mp), Adriana Prodeus (ap), 13.11 NH8 20:00 Wonder Women!… Ewa Szabłowska (es), Magdalena Sztorc (MS), K. Guevara-Flanagan, 79’ wtorek Anna Tatarska (at). 10:0011:00 12:0013:00 14:0015:00 16:0017:00 18:0019:00 20:0021:00 22:0023:00 NH1 18:00 Gangster 20:45 4:44 Ostatni dzień na Ziemi Lawless 4:44 Last Day on Earth J. Hillcoat, 116’ A. Ferrara, 82’ american docs NH6 10:00 Podróże Neila Younga 12:30 Ja@wZoo 15:15 Jak przetrwać epidemię 18:00 Dziewczyna w masce lisicy 20:45 Bayou Blue Neil Young Yourneys Me@theZoo How to Survive a Plague White Fox Mask Bayou Blue J. -

A Level Film Studies Candidate Style Answers

Qualification Accredited A LEVEL Candidate Style Answers FILM STUDIES H410 For first teaching in 2017 H410/02 Critical approaches to film Version 1 www.ocr.org.uk/filmstudies A Level Film Studies Candidate Style Answers Contents Introduction 3 Section A Question 2: Level 5 answer 4 Commentary 6 Section A Question 2: Level 3 answer 7 Commentary 7 Section B Question 4: Level 5 answer 8 Commentary 10 Section B Question 4: Level 3 answer 11 Commentary 11 Section C Question 5: Level 5 answer 12 Commentary 14 Section C Question 5: Level 3 answer 15 Commentary 16 Section C Question 7: Level 5 answer 17 Commentary 19 Section C Question 7: Level 3 answer 20 Commentary 21 Section C Question 10: Level 5 answer 22 Commentary 24 Section C Question 10: Level 3 answer 25 Commentary 25 2 © OCR 2018 A Level Film Studies Candidate Style Answers Introduction Please note that this resource is provided for advice and guidance only and does not in any way constitute an indication of grade boundaries or endorsed answers. Whilst a senior examiner has provided a possible level for each Assessment Objective when marking these answers, in a live series the mark a response would get depends on the whole process of standardisation, which considers the big picture of the year’s scripts. Therefore the level awarded here should be considered to be only an estimation of what would be awarded. How levels and marks correspond to grade boundaries depends on the Awarding process that happens after all/most of the scripts are marked and depends on a number of factors, including candidate performance across the board. -

Race in Hollywood: Quantifying the Effect of Race on Movie Performance

Race in Hollywood: Quantifying the Effect of Race on Movie Performance Kaden Lee Brown University 20 December 2014 Abstract I. Introduction This study investigates the effect of a movie’s racial The underrepresentation of minorities in Hollywood composition on three aspects of its performance: ticket films has long been an issue of social discussion and sales, critical reception, and audience satisfaction. Movies discontent. According to the Census Bureau, minorities featuring minority actors are classified as either composed 37.4% of the U.S. population in 2013, up ‘nonwhite films’ or ‘black films,’ with black films defined from 32.6% in 2004.3 Despite this, a study from USC’s as movies featuring predominantly black actors with Media, Diversity, & Social Change Initiative found that white actors playing peripheral roles. After controlling among 600 popular films, only 25.9% of speaking for various production, distribution, and industry factors, characters were from minority groups (Smith, Choueiti the study finds no statistically significant differences & Pieper 2013). Minorities are even more between films starring white and nonwhite leading actors underrepresented in top roles. Only 15.5% of 1,070 in all three aspects of movie performance. In contrast, movies released from 2004-2013 featured a minority black films outperform in estimated ticket sales by actor in the leading role. almost 40% and earn 5-6 more points on Metacritic’s Directors and production studios have often been 100-point Metascore, a composite score of various movie criticized for ‘whitewashing’ major films. In December critics’ reviews. 1 However, the black film factor reduces 2014, director Ridley Scott faced scrutiny for his movie the film’s Internet Movie Database (IMDb) user rating 2 by 0.6 points out of a scale of 10. -

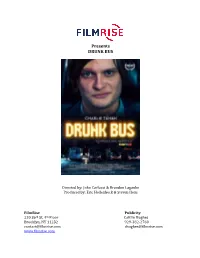

Presents DRUNK BUS

Presents DRUNK BUS Directed by: John Carlucci & Brandon Laganke Produced by: Eric Hollenbeck & Steven Ilous FilmRise Publicity 220 36th St, 4th Floor Caitlin Hughes Brooklyn, NY 11232 929-382-2760 [email protected] [email protected] www.filmrise.com DRUNK BUS RT: 100 minutes SHORT SYNOPSIS Michael (Charlie Tahan) is a recent graduate whose post college plan is derailed when his girlfriend leaves him for a job in New York City. When the bus service hires a security guard to watch over the night shift, Michael comes face to tattooed face with Pineapple, a 300-lb punk rock Samoan who challenges him with a kick in the ass to break from the loop and start living or risk driving in circles forever. LONG SYNOPSIS Michael (Charlie Tahan) is a recent graduate whose post college plan is derailed when his girlfriend leaves him for a job in New York City. Stuck in Ohio without a new plan of his own, Michael finds himself caught in the endless loop of driving the "drunk bus," the debaucherous late-night campus shuttle that ferries drunk college students from parties to the dorms and back. When the bus service hires a security guard to watch over the night shift, Michael comes face to tattooed face with Pineapple, a 300-lb punk rock Samoan who challenges him with a kick in the ass to break from the loop and start living or risk driving in circles forever. DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT We are very fortunate to have found that partner in our producer, Eric Hollenbeck (NATIVE SON, TOMORROW MAN, KINGS OF SUMMER), who immediately supported our creative vision, believed Pineapple could hold his own on screen and knew we were capable of the task ahead. -

Everybody's Authority

Natalia Cecire Everybody’s Authority The incursion of the unwanted thus seems to be part of the risk of thinking with others, part of the vulnerability of opening oneself, one’s words and one’s thoughts, to anyone who might venture upon them. —Jodi Dean, “Blogging Theory” Ah, the peace and quiet that follows a “block” on twitter. —Saree Makdisi, Twitter One day in 2012, while a presidential election campaign was in full swing, I wrote a blog post and hit “publish.” The post was pretty niche, I thought—the ninth in a series of posts that I had been tagging “puerility,” all incipient ideas for a future project that would draw on childhood studies, history of statistics, and poetics. With “puerility,” I sought to describe a ludic epistemological mode that draws its power from its very willingness to disclaim power and embrace provisionality—an ambivalence often figured through, and associated with, boyhood.1 Previous blogging on puerility had mused over the Google N- gram Viewer and the widespread propensity to describe it as a “fun” “toy”; the foul- mouthed parody Twitter account @MayorEmanuel, and Wes Anderson’s 2012 film Moonrise Kingdom. The new post was about election predictions and a recent media flap around the statistician Nate Silver. I was halfway down a badly damaged post-Hurricane Sandy east coast, at a workshop at the University of Maryland, College Park, before I realized that, due to Silver’s celebrity and thanks to a senior economist’s denunciation, the piece had “jumped platforms.” From my usual audience of mostly junior fellow humanities academics, most of them known to me in person, the piece had moved to a different audience, to whom conceptual frameworks that I take for granted were both alien and offensive: the literary distinction between person and persona, the gender studies distinction between descriptive and prescriptive accounts of gendering, the history of science premise that the making of facts is both social and processual. -

Moonrise Kingdom

presenta MOONRISE KINGDOM un film di Wes Anderson ufficio stampa Via Chinotto, 16 tel +39 06.3759441 fax +39 06.37352310 Alessandra Tieri (+39 335.8480787 [email protected]) Georgette Ranucci (+39 335.5943393 [email protected]) CAST ARTISTICO Bruce Willis Comandante Sharp Edward Norton Capo scout Ward Bill Murray Signor Bishop Frances McDormand Signora Bishop Tilda Swinton Responsabile dei Servizi Sociali Jared Gilman Sam Kara Hayward Suzy Jason Schwartzman Cugino Ben Bob Balaban Il narratore CAST TECNICO Regia Wes Anderson Sceneggiatura Wes Anderson Roman Coppola Fotografia Robert Yeoman Montaggio Andrew Weisblum Scenografia Adam Stockhausen Costumi Kasia Walicka Maimone Musiche Alexandre Desplat Wes Anderson Produzione Scott Rudin Steven Rales Jeremy Dawson durata 94’ CREDITI NON CONTRATTUALI 2 SINOSSI Ambientato in un’isola al largo delle coste del New England nell’estate del 1965, Moonrise Kingdom racconta la storia di due dodicenni che si innamorano, stringono un patto segreto e fuggono insieme nella foresta. Mentre le autorità li cercano, una violenta tempesta al largo dell’isola sta per scatenarsi, e la pacifica comunità locale verrà messa completamente a soqquadro. CREDITI NON CONTRATTUALI 3 NOTE DI PRODUZIONE Per Anderson la decisione di scegliere per il ruolo dei protagonisti del film due debuttanti, praticamente senza alcuna esperienza, avrebbe potuto rivelarsi molto rischiosa. Ma, come osserva Jeremy Dawson produttore di Moonrise Kingdom , “Wes Anderson si fida del suo istinto, così ha scelto i due che riusciva a immaginare bene nei panni dei protagonisti e, ancora una volta, ha messo a segno un colpo da maestro in termini di casting”. I giovanissimi Jared Gilman e Kara Hayward hanno convinto Anderson in momenti diversi durante quello che è stato il lungo percorso necessario a mettere insieme il cast. -

Experiencing Reel Spirituality Spirituality and Film

Experiencing Reel Spirituality Spirituality and Film Theme Speaker The Rev. Douglas E. Wadkins Camp Eliot August 2013 Day 1 The Daily Round “Let the Great World Spin” Day 2 Joy and Laughter “To Truly Laugh” Day 2 Joy and Laughter “To Truly Laugh” Day 3 Sadness & Loss "It's Not That I am Afraid to Die..." Day 4 Forgiveness, Faith, Fear & Film The Fantastic Four (?) Day 4 Forgiveness, Faith, Fear & Film The Fantastic Four (?) Day 5 Love and Other Redemptions Day 6 “The Play’s the Thing” Befriending Film Frederic and Mary Ann Brussat 1. Be Prepared 2. Remember your intention to be hospitable 3. Connect with the characters Befriending Film 4. Pay attention to your reactions 5. Consider the significance of what you are seeing 6. Look for the bigger picture Befriending Film 7. Watch for epiphanies 8. Don’t turn away from the shadow 9. Let the movie simmer Frederic and Mary Ann Brussat Links Home Page: http://www.spiritualityandpractice.com Spirituality & Film: http://www.spiritualityandpractice.com/films Rotten Tomatoes Critic Page: http://www.rottentomatoes.com/critic/frederic-and-mary-ann-brussat Filmography 1 Baraka. Dir. Ron Fricke. Magidson Films, 1992. Film. Beasts of the Southern Wild. Dir. Benh Zeitlin. Perf. Quvenzhané Wallis, Dwight Henry, Jovan Hathaway et al. Cinereach, 2012. Film. Defending Your Life. Dir. Albert Brooks. Perf. Albert Brooks, Michael Durrell, Lee Grant, Meryl Streep et al. Producer Robert Grand, 1991. Film. The Descendants. Dir. Alexander Payne. Perf. George Clooney, Patricia Hastie et al. Fox Searchlight Pictures, 2011. Film. The Impossible. Dir. J.A. Bayona. Perf. -

Diplomarbeit

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „The Quirky in the Work of Wes Anderson. Metamodern Oscillations at the Basis of a Quirky Sensibility“ Verfasser Stefan Heiden Angestrebter akademischer Grad Magister der Philosophie (Mag. Phil.) Wien, im Dezember 2012 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt A 190 344 299 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt UF Englisch (und UF Psychologie und Philosophie) Betreuer Prof. Dr. Stefan L. Brandt Declaration of Authenticity I confirm to have conceived and written this paper in English all by myself. Quotations from other authors and any ideas borrowed and/or passages paraphrased from the words of other authors are all clearly marked within the text and acknowledged in the bibliographical references. Vienna, in December 2012 Thank you, Anna. iii Acknowledgements First, I would like to show my gratitude to my supervisor, Prof. Dr. Stefan L. Brandt, for his ideas and advice in countless issues and for his great encouragement and reliability. Many thanks to my family, especially my mother. This diploma thesis would not have been possible without your great support. I would also like to seize the opportunity to express my warmest thanks to all those people who have encouraged me or lent me an ear in the course of my studies. Special thanks to my dear friends, Michi, Daniel and Robert. v Table of Contents 1. Introduction................................................................................................................................. 1 1.1. Outline.................................................................................................................................