Rainforest Coffee Products Pte Ltd V Rainforest Cafe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Landry's Inc. Appoints New Additions to Destination Sales Team

Media Contact: Colleen Enis, [email protected] Mary Ann Cuellar, [email protected] Dancie Perugini Ware Public Relations (713) 224- 9115 LANDRY’S INC. APPOINTS NEW ADDITIONS TO DESTINATION SALES TEAM GALVESTON, TEXAS- Landry’s, Inc., a multinational, diversified restaurant, hospitality, gaming and entertainment company based in Houston, Texas, is pleased to announce that Robert Gregory and Katherine Hughes have been hired as Sales Managers at The San Luis Resort. In addition, Gregory and Hughes will be joining a team of seasoned hospitality professionals including Allison Vasquez, Nancy C. Van Bramer, Beth Wehrman and Mary Elizabeth Pennington. In his new position, Gregory will promote and sell The San Luis Resort properties to clients in the social, military, education, fraternal and corporate group markets for meetings and events. No stranger to the world of sales, he has held previous positions in the hospitality industry. As Sales Manager, Katherine Hughes will book group rooms, meeting and events for the social, military, education and fraternal markets. Most recently, she held the position of Dual Director of Sales. Allison Vasquez, a 13-year San Luis veteran and sales manager, has a rich background in sales and hospitality management. In her new position, Vasquez focuses on Houston corporate, Med Center, higher education, federal government, and Southeast government/association accounts. Nancy C. Bramer, a 25-year veteran and sales manager, focuses on state & regional associations. Beth Wehrman, an 11-year veteran and sales manager focuses on Dallas corporate. Mary Elizabeth Pennington, sales manager and Texas A&M University Graduate, began her career in sales as an intern at The San Luis. -

Menlo Park Mall 55 Parsonage Rd Edison, NJ 08837

Menlo Park Mall 55 Parsonage Rd Edison, NJ 08837 REGULAR CENTER HOURS PHONE NUMBERS Monday to Thursday 11:00AM - 8:00PM Friday to Saturday 10:00AM - 9:00PM Mall Office: Shopping Line: Mall Security: Sunday 11:00AM - 7:00PM (732) 549-1900 (732) 494-6255 (732) 494-6255 Store Name Store Phone # Mall Entrance Tip Location Info A Dollar & Change (732) 205-0501 Entrance next to the Rainforest Cafe Located on the lower level Macy's wing next to Rainforest Cafe and Embroidery Place Adidas (732) 906-7826 Entrance between Cheesecake Factory and Barnes & Noble Lower level near center court. Next to the up escalator Aerie (732) 548-1056 Upper level parking deck next to Havana Central and Chipotle Located on the upper level next to Champs Sports and Garage Aeropostale (732) 549-0583 Upper Level parking deck next to Macy's Located on the upper level Macy's wing, next to Against All Odds Against All Odds (848) 271-6006 Located Upper Level Macy's Wing, next to Aeropostale. Aldo (732) 548-9669 Upper Level parking deck next to AMC Dine In Theater Locacted on the upper level near Center Court between Pandora and Swarovski Alexa's Little Boutique (646) 920-8838 Entrance next to the Rainforest Cafe Located on the lower level Macy's wing next to Unisex Hair Salon and Co-Cool Smoothie & Bubble Tea AMC Theatres (732) 321-9093 Upper Level Rear Parking Deck Upper Level Rear Parking Deck American Eagle Outfitters (732) 744-9380 Entrance next to the Rainforest Cafe Located on the lower level Macy's wing between Journey's and Urban Outfitters Store Name Store Phone # Mall Entrance Tip Location Info American Hide (732) 452-1100 Upper level parking deck next to Macy's Upper level Macy's wing next to Next Exit. -

Morton's the Steakhouse, Mccormick & Schmick's, Mastro's, Mitchell's

Heather Grobaski Morton's The Steakhouse, McCormick & Schmick's, NATIONAL ACCOUNTS MANAGER Mastro's, Mitchell's Fish Market, Chart House, Landry's, Inc. Landry's Seafood, Vic & Anthony's, Oceanaire and many more... 7 CUISINE DINING ROOM 1 SEATED ROOM 2 SEATED ROOM 3 SEATED ROOM 4 SEATED ROOM 5 SEATED ROOM 6 BANQUET CAPACITY BANQUET CAPACITY BANQUET CAPACITY BANQUET CAPACITY BANQUET CAPACITY BANQUET [email protected] P = Private Space EXPERIENCE w) 713-386-8011 S = Semi-Private Space CAPACITY BANQUET SEATED CAPCITY ROOM SEATED Landry's Seafood House - Birmingham 139 State Farm Parkway Birmingham AL 35209 Seafood Casual Room 45 Landry's Seafood House - Huntsville 5101 Governor's House Dr. Huntsville AL 35805 Seafood Casual Room 45 ARIZONA Claim Jumper 10125 W. McDowell Rd Avondale Casual Claim Jumper 3063 W Aqua Fria Freeway Phoenix Casual Chart House - Scottsdale 7255 McCormick Parkway Scottsdale AZ 85258 Seafood Fine Dining Room 40 Room 65 Comb 110 Cam 35 LAW 250 Morton's The Steakhouse 15233 N Kierland Blvd Scottsdale Fine Dining BDRM 32 BDR 32 BDRM 72 Mastro's Steakhouse 8852 East Pinnacle Peak Road Scottsdale Arizona 85255 Gina Stanghellini Fine Dining Domin 16 East 65 West 110 The 28 The 28 Mastro's Steakhouse 6991 E. Camelback Road cottsdale (City Ha Arizona 85251 Suzanne (Suzi) A Fine Dining Mastro 24 Mast 24 Mastro 24 Mast 48 Mas 72 Mayor's Off 92 Mastro's Steakhouse - Ocean Club 15045 North Kierland Blvd Scottsdale Arizona Fine Dining North M 20 Sout 30 Mastro 50 East 33 We 33 North Deck 76 East Pier 20 Rainforest Cafe - Tempe Arizona Mills 5000 S. -

Case Study for Landry's

skillnetinc.com f i l CASE STUDY Landry’s record breaking 6 month Merchandise Operations Management and Stores implementation delivered by SkillNet CHALLENGES INDUSTRY Landry’s was looking to modernize and streamline its retail operations across its various locations and Specialty Retail establishments throughout the US to support an expected period of rapid expansion in 2015. Landry’s Dining, Hospitality, Entertainment, Gaming directly manages 10-15 retail locations in each of its Golden Nugget Casino locations. Additionally, Landry’s handles a variety of restaurant locations, such as the well known Rainforest Cafe, that contain retail operations within their gift shops. Both their casino and dining enterprises offer their customers loyalty rewards programs requiring that their new platform be seamlessly integrated for improved customer relationship management. Landry’s aimed to align their portfolio of various dining, hospitality, entertainment, and gaming establishments to run on a standardized merchandising and planning platform for better visibility and tracking of sales, inventory, and customer loyalty for their retail product Landry’s, Inc. is an American privately owned, assortment. In addition to the challenge of aligning these various retail establishments, Landry’s set an multi-brand dining, hospitality, entertainment, and aggressive timeline of implementing its new platform in an unprecedented six month time period, and gaming corporation based in Houston, Texas. They SkillNet swiftly delivered. own and operate more than 450 restaurant, hotel, casino, and entertainment destinations in 35 states and the District of Columbia. The company RAPID, 6 MONTH MERCHANDISE OPERATIONS MANAGEMENT AND also owns and operates numerous international locations. Landry’s is among the nation’s largest STORES IMPLEMENTATION and fastest-growing restaurant corporations. -

Grapevine (Dallas), Texas Best of Both Worlds

BUSINESS CARD DIE AREA 5425 Wisconsin Avenue, Suite 300 Chevy Chase, MD 20815 (301) 968-6000 simon.com Information as of 5/1/16 Simon is a global leader in retail real estate ownership, management and development and an S&P 100 company (Simon Property Group, NYSE:SPG). GRAPEVINE (DALLAS), TEXAS BEST OF BOTH WORLDS Dallas/Fort Worth is a market of more than seven million people—the fourth largest market in the United States. Grapevine Mills,® just north of Dallas and Fort Worth, is perfectly positioned to serve the entire market. — The Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport, just two miles south of the center, is the fourth busiest airport in the world, with 90 international flights landing daily from 30 countries. — Dallas/Fort Worth is one of the most visited tourist markets in the United States, with shopping being a significant reason for visiting. — Home to the Gaylord Texan Resort and Convention Center, one of the largest in the country, boasting over 1,600 guest rooms and 400,000 square feet of meeting space. — The Dallas/Fort Worth metroplex is growing by 100,000 residents every year. — The Dallas/Fort Worth area ranked number two for most job growth in the U.S. in 2014. — From historical attractions to natural wonders, this area has something for everyone to love. TEXAS-SIZED SAVINGS Grapevine Mills® is the premier retail and entertainment destination in the Dallas/Fort Worth area and features the best names in value and retail outlets. — A significant renovation of the center’s common area was recently completed to create a new upscale, timeless look. -

CREATIVE INSPIRATION How Schussler Creative Brings One-Of-A-Kind Restaurants to Life

LEADING THE WAY THROUGH THE 21ST CENTURY ® MAY 2019 CREATIVE INSPIRATION How Schussler Creative brings one-of-a-kind restaurants to life. LEADING THE WAY THROUGH THE 21ST CENTURY ON THE COVER ® Schussler Creative and its enthu- MAY 2019 siastic founder, Steve Schussler — the force behind Rainforest ® CREATIVE Café, T-Rex and The Boathouse — INSPIRATION How Schussler Creative brings inspire the retail industry to break one-of-a-kind restaurants to life. out of the box and think big, see page 76. Cover designed by Nick Topolski. VOLUME 24 ISSUE 1 May 2019 shoppingcenterbusiness.com DEPARTMENTS FEATURES 14 NEWSLINE 76 | CREATIVE INSPIRATION Schussler Creative and its enthusiastic founder, Steve Schussler — the force behind 46 CAPITAL MARKETS Rainforest Café, T-Rex and The Boathouse — inspire the retail industry to break out of the box and think big. 58 DEVELOPMENT NEWS Randall Shearin 255 CLASSIFIED 94 | FOOD IS FRONT AND CENTER Retail centers will feature more food and beverage retailers than ever, making the REVIEWS delivery disruption a top concern. John Nelson 68 | FUN FOR EVERYONE Texas-based entertainment venue PINSTACK offers 102 | FOR CAFARO, CONSISTENCY IS KEY experiences for all ages. Cafaro celebrates its 70th anniversary with an eye toward the future. Katie Sloan Coleman Wood 72 | GREEK ON THE GO 108 | TRANSACTIONS INCREASE IN NET LEASE SECTOR Fast-casual restaurant The Great Greek offers A return to historically low interest rates after a late 2018 hike drives investment. authentic Mediterranean eats for an active lifestyle. John Gorman Katie Sloan 116 | RECIPE FOR SUCCESSFUL MIXED-USE DEVELOPMENT A patient timeline and creation of an organic neighborhood are key ingredients to developers serving up winning projects. -

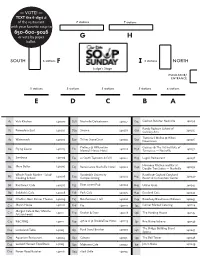

F I G H E D C

— VOTE! — TEXT the 6-digit # of the restaurant 7 stations 7 stations with your favorite soup to 650-600-9016 or vote by paper GH ballot. SOUTH 6 stations F I 6 stations NORTH Judgeʼs Stage ESCALATOR/ ENTRANCE 5 stations 5 stations 5 stations 5 stations 4 stations EDCBA A1 Vui’s Kitchen 140200 D18 Noshville Delicatessen 140217 G35 Cochon Butcher Nashville 140234 Randy Rayburn School of A2 Pomodoro East 140201 D19 Sinema 140218 G36 140235 Culinary Arts Trattoria Il Mulino @ Hilton A3 Watermark 140202 E20 TriStar StoneCrest 140219 G37 140236 Downtown Pralines @ Millennium Courses @ The Art Institute of A4 Flying Saucer 140203 E21 140220 H38 140237 Maxwell House Hotel Tennessee — Nashville B5 Sambuca 140204 E22 12 South Taproom & Grill 140221 H39 Lugo’s Restaurant 140238 Harmony Kitchen and Bar at B6 Mere Bulles 140205 E23 Renaissance Nashville Hotel 140222 H40 140239 Double Tree Suites — Nashville Whole Foods Market - Salud! Vanderbilt University Ravello @ Gaylord Opryland B7 140206 E24 140223 H41 140240 Cooking School Campus Dining Resort & Convention Center B8 Rainforest Cafe 140207 F25 Fleet Street Pub 140224 H42 Urban Grub 140241 B9 Sidekick’s Cafe 140208 F26 Park Cafe 140225 H43 Eastland Cafe 140242 C10 Chaffin’s Barn Dinner Theatre 140209 F27 Butchertown Hall 140226 H44 Broadway Brewhouse Midtown 140243 C11 Marsh House 140210 F28 Etc. 140227 I45 Corner Market Catering 140224 Margot Cafe & Bar/ Marche C12 140211 F29 Decker & Dyer 140228 I46 The Harding House 140245 Artisan Foods C13 B&C BBQ 140212 F30 4th & U @ DoubleTree Hotel 140229 -

Kiss Nature Goodbye

This article appeared in Harvard Design Magazine, Winter/Spring 2000, Number 10. To order this issue or a subscription, visit the HDM homepage at <http://mitpress.mit.edu/HDM>. © 2001 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College and The MIT Press. Not to be reproduced without the permission of the publisher Kiss Nature Goodbye Marketing the Great Outdoors, by John Beardsley HATS OFF TO commodity culture. The ture is emblematic of a larger phenom- endless quest for new products has enon. I refer to the growing commodi- spawned another hot-selling hybrid: fication of nature: the increasingly the not-entirely-entertaining, but not- pervasive commercial trend that views really-educational, simulated “natural” and uses nature as a sales gimmick or attraction. At the Mall of America, it’s marketing strategy, often through the called UnderWater World. You pay production of replicas or simulations. $10.95, go down the escalator, and en- Commodification through simulation ter a dark chamber where synthetic is most obvious in the “landscapes” of leaves in autumnal tints rustle as you the theme park and the shopping mall. pass. You’re in a gloomy boreal forest Such places have been widely discussed in the fall, descending a ramp past bub- of late: the malling and theming of the bling brooks and glass-fronted tanks public environment and the prevalence stocked with freshwater fish native to of simulation as a cultural form have the northern woodlands. At the bottom elicited skeptical commentary from, of the ramp, you step onto a moving among others, philosopher Jean Bau- walkway and are transported through a drillard, architectural historian Mar- 300-foot-long transparent tunnel garet Crawford, essayist Joan Didion, carved into a 1.2-million-gallon aquari- novelist and semiologist Umberto Eco, um. -

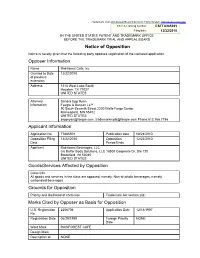

Notice of Opposition Opposer Information Applicant Information

Trademark Trial and Appeal Board Electronic Filing System. http://estta.uspto.gov ESTTA Tracking number: ESTTA385393 Filing date: 12/22/2010 IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD Notice of Opposition Notice is hereby given that the following party opposes registration of the indicated application. Opposer Information Name Rainforest Cafe, Inc. Granted to Date 12/22/2010 of previous extension Address 1510 West Loop South Houston, TX 77027 UNITED STATES Attorney Sandra Epp Ryan information Faegre & Benson LLP 90 South Seventh Street 2200 Wells Fargo Center Minneapolis, MN 55402 UNITED STATES [email protected], [email protected] Phone:612.766.7196 Applicant Information Application No 77886501 Publication date 08/24/2010 Opposition Filing 12/22/2010 Opposition 12/22/2010 Date Period Ends Applicant Rainforest Beverages, LLC c/o Better Body Solutions, LLC 18500 Corporate Dr, Ste 120 Brookfield, WI 53045 UNITED STATES Goods/Services Affected by Opposition Class 032. All goods and services in the class are opposed, namely: Non-alcoholic beverages, namely, carbonated beverages Grounds for Opposition Priority and likelihood of confusion Trademark Act section 2(d) Marks Cited by Opposer as Basis for Opposition U.S. Registration 2256706 Application Date 12/18/1997 No. Registration Date 06/29/1999 Foreign Priority NONE Date Word Mark RAINFOREST CAFE Design Mark Description of NONE Mark Goods/Services Class 035. First use: First Use: 1994/09/02 First Use In Commerce: 1994/10/03 RETAIL STORE SERVICES LOCATED ON THE PREMISES OF A RESTAURANT, AND ON-LINE ORDERING SERVICES, FEATURING SOUVENIRS AND OTHER GENERAL MERCHANDISE GIFTWARE Class 042. -

Landry's Inc. Locations by State

LANDRY’S INC. LOCATIONS BY STATE ALABAMA Temecula - CJ Downers Grove - BHT MISSOURI Clackamas - CJ McAllen - SG Birmingham - LSH Thousand Oaks - MAS Gurnee - RFC Branson - JCS, LSH, SG Portland - CHT, MRT, MS McKinney - SG Huntsville - LSH Valencia - CJ Lombard - CJ Des Peres - MS Tigard - MS Mesquite - SG ARKANSAS Woodland Hills - MRT Naperville - MRT Kansas City - MS Tualatin - CJ Midland - SG Little Rock - SG COLORADO Northbrook - MRT St. Louis - LSH, MRT PENNSYLVANIA Odessa - SG Oak Brook - MS Pasadena - SG ARIZONA Colorado Springs - SG NEVADA King of Prussia - MRT Rosemont - MRT, MS Pearland - SG Avondale - CJ Denver - AQ, BG, MRT, Henderson - CJ Philadelphia - CHT, MRT, MS Schaumburg - MRT, RFC Plano - JCS, SG Phoenix - CJ MS, OCE Lake Tahoe - CHT Pittsburgh - BB, GC, JCS, Village of Hoffman Estates - CJ Port Arthur - SG Scottsdale - CHT, MAS, MRT Englewood - LSH Las Vegas - BG, CAD, CHT, MC, MRT, MS Rockwall - SG Tempe - CJ, JCS, RFC Golden - CHT, SS INDIANA CJ, GN, GRT, LIL, MAS, MRT, PUERTO RICO Round Rock - JCS, SG Tucson- CJ Parker - SG Carmel - MC RED, RFC, SH, TLB, TRV, V&A San Juan - MRT Westminster - SG Indianapolis - MRT, MS, OCE San Antonio - JCS, LSH, RFC, CALIFORNIA Laughlin - BG, CJ, GN, SG RHODE ISLAND DELAWARE KENTUCKY Reno - CJ SG, TOA/CHT, MRT Anaheim - BG, MRT, MS, RFC Providence - MS San Marcos - SG Wilmington - JCS Bellevue - JCS Summerlin - CJ Anaheim - Disneyland - RFC SOUTH CAROLINA Shenandoah - BAB, SG Louisville - BHT, JCS, MC, MRT NEW JERSEY Beverly Hills - MAS, MRT FLORIDA Charleston - BG Sugar Land - -

Rainforest Cafe Speciality

® = RAINFOREST CAFE SPECIALITY All smoothies are delightfully blended with our own recipe, low-fat frozen yoghurt and CONTAIN MILK VERY BERRY #WORLDSBESTSMOOTHIE £6.90 High in antioxidants & great for circulation! Blackberry, blueberry, raspberry, strawberry & cranberry juice. MONTY’S PYTHON £6.90 Strawberry, grape & cranberry juice. Excellent immune booster! SHEBA’S JUNGLE JUICE £6.90 Oreo® cookies & coffee. COCKATOO COCKTAIL £6.90 Kiwi, banana, strawberry & cranberry juice. High in Vitamin C! TROPICAL CHA! CHA! £6.90 Mango, pineapple & passion fruit. Energy boosting! JUST PLAIN £6.90 Strawberry, chocolate, banana or vanilla. KIDS SMOOTHIE £4.20 All the above flavours available in a 9oz. glass. Rainforest Cafe’s environmentally friendly water is washing away carbon footprints, leaving only the natural air. The only footprint to be seen is that of the wildlife around us. Still or Sparkling (Litre) £5.90 Still or Sparkling (330ml) £4.20 Tap water available on request. (Rainforest Cafe donates 25p from each sale of this dish to help World Land Trust preserve the rainforest in Ecuador RAINFOREST RICKY £6.90 Pineapple, apple, strawberry, orange & grapefruit juice. Stimulates digestion! JUNGLE ROOT £6.95 Freshly juiced carrot. High in Vitamin A - excellent for skin & eyes! AMAZON ENERGY £6.95 Freshly juiced carrot, apple & ginger. Great detox & energiser! MEDICINE MANMEDICINE MAN £6.95 Freshly juiced carrot, celery & apple. Cleansing & energising! CONTAINS CELERY SUPER BERRY £6.95 Freshly juiced raspberry, blackberry, strawberry, blueberry & cranberry. Excellent for immune system! FRESH LEMONADE £4.50 ORANGE, PINEAPPLE, GRAPEFRUIT OR APPLE JUICE £4.50 Kid’s Juice Apple or Orange £3.20 NATALIA’S ROSIE CHEEKS £5.90 A kid’s mocktail of blackcurrant, apple & orange cordial, served up in our special Rainforest Palm Tree Plastic glass that you can take home with you afterwards. -

Position Cultural Exchange Activities Employer Information Why Choose

Employer Information Employer name: Rainforest Cafe Grapevine Type of business: Restaurant Job location: Rainforest Cafe Grapevine City: Grapevine Mills State: TX Zip: 76051 Website: Why choose us? Located only 20 miles outside of Dallas, in a mall. Fun, upbeat atmosphere with plenty to do in the local area! Cultural exchange activities Area includes lakes, mall, local Main Street, etc. Not far away are large attractions such as Legoland Discover Center, sea Life Grapevine Aquarium, Six Flags Over Texas, Texas Rangers, Dallas Cowboys, Dallas Mavericks, plus more. Right in town is the Grapevine Vintage Railroad, 10 Gallon Tours, Great Wolfe Lodge to name a few. Position Job title: Host, Food Runner Job description and required skills: Fluent or high Adv. English. Must have a great phone presence and be understood clearly. Greeting & seating guests, assisting servers with filling waters, clearing tables, restocking host station, making guest reservations over the phone and in person. Must be very outgoing. Personality & professional appearance is key. Must have a positive attitude, be understanding and compassionate in a friendly & helpful way. Must like dealing with people. Requires attention to detail, punctuality, and a great service attitude. Will be cross trained in other positions as well. English level required: advanced Hourly wage (before taxes): 5.25 + tips Position ID: 28676 Employer: Rainforest Cafe Grapevine Position: Host, Food Runner Page: 1 Position Information Tips: yes Bonus: no Estimated hours per day: 8-10 Number of days