Douglas Hofstadter 18

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analogy As the Core of Cognition

Analogy as the Core of Cognition by Douglas R. Hofstadter Once upon a time, I was invited to speak at an analogy workshop in the legendary city of Sofia in the far-off land of Bulgaria. Having accepted but wavering as to what to say, I finally chose to eschew technicalities and instead to convey a personal perspective on the importance and centrality of analogy-making in cognition. One way I could suggest this perspective is to rechant a refrain that I’ve chanted quite oft in the past, to wit: One should not think of analogy-making as a special variety of reasoning (as in the dull and uninspiring phrase “analogical reasoning and problem-solving,” a long-standing cliché in the cognitive-science world), for that is to do analogy a terrible disservice. After all, reasoning and problem-solving have (at least I dearly hope!) been at long last recognized as lying far indeed from the core of human thought. If analogy were merely a special variety of something that in itself lies way out on the peripheries, then it would be but an itty- bitty blip in the broad blue sky of cognition. To me, however, analogy is anything but a bitty blip — rather, it’s the very blue that fills the whole sky of cognition — analogy is everything, or very nearly so, in my view. End of oft-chanted refrain. If you don’t like it, you won’t like what follows. The thrust of my chapter is to persuade readers of this unorthodox viewpoint, or failing that, at least to give them a strong whiff of it. -

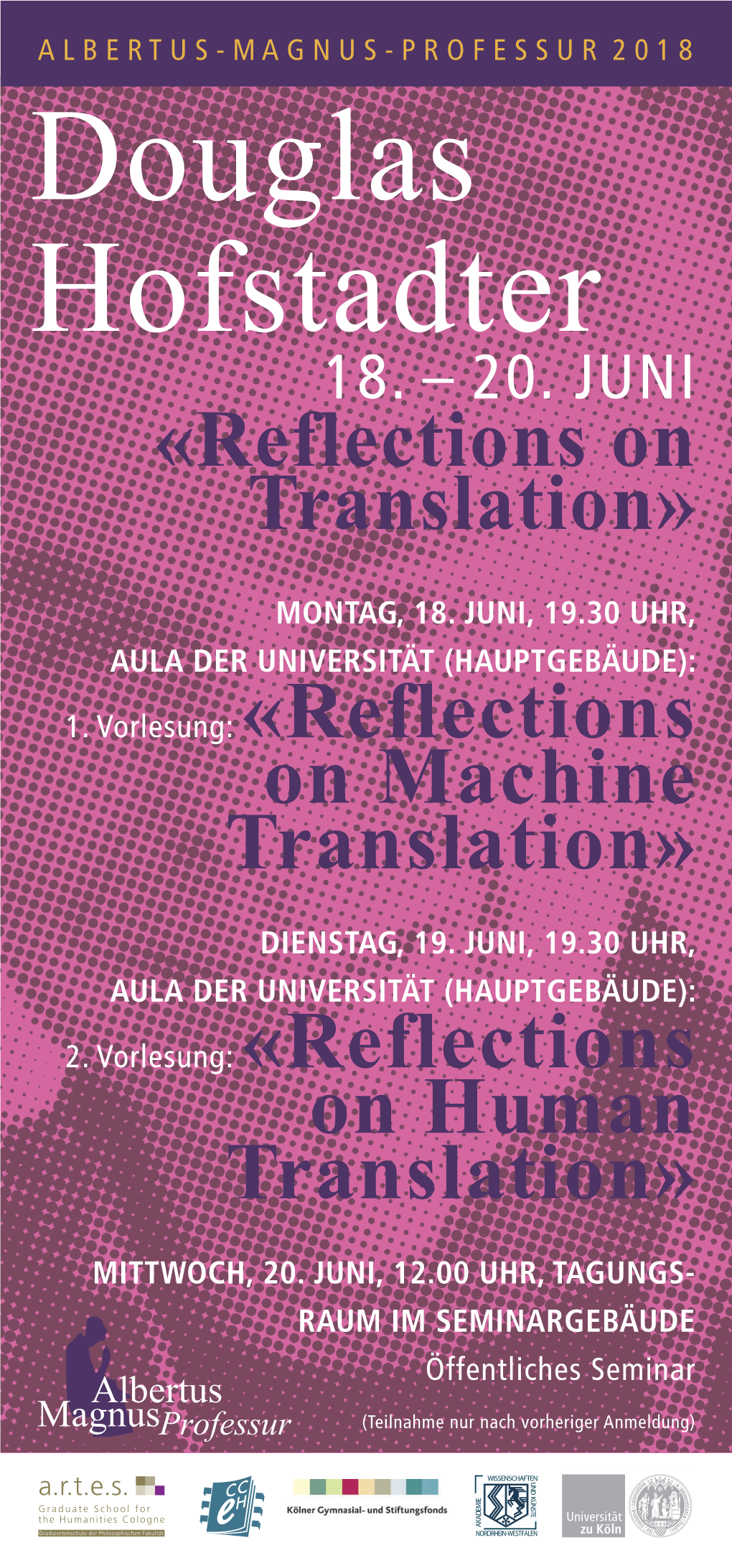

I Am a Strange Loop by DOUGLAS HOFSTADTER

I am a Strange Loop by DOUGLAS HOFSTADTER Outline, Highlights, & Discussion Topics Judging a Book by its Cover (or dust jacket) What do we mean when we say “I”? Can a self, a soul, a consciousness, an “I” arise out of mere matter? If it cannot, then how can you or I be here? If it can, then how can we understand this baffling emergence? Deep down, a human brain is • a chaotic seething soup of particles, • on a higher level it is a jungle of neurons, • and on a yet higher level it is a network of abstractions that we call “symbols”. The most central and complex symbol in your brain or mine is the one we both call “I”. An “I” is a strange loop in a brain where symbolic and physical levels feed back into each other and flip causality upside down, with symbols seeming to have free will and to have gained the paradoxical ability to push particles around, rather than the reverse. For each human being, this “I” seems to be the realest thing in the world. But how can such a mysterious abstraction be real — or is our “I” merely a convenient fiction? Does an “I” exert genuine power over the particles in our brain, or is it helplessly pushed around by the all- powerful laws of physics? How do we mirror other beings inside our mind? Can many strange loops of different “strengths” inhabit one brain? If so, then a hallowed tenet of our culture — that one human brain houses one human soul — is an illusion. -

THE BIOLOGICAL PHYSICIST the Newsletter of the Division of Biological Physics of the American Physical Society Vol 2 No 6 Feb 2003

THE BIOLOGICAL PHYSICIST The Newsletter of the Division of Biological Physics of the American Physical Society o Vol 2 N 6 Feb 2003 DIVISION OF BIOLOGICAL PHYSICS EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE In this Issue Chair FEATURE Robert Austin An Eternal Golden Braid: [email protected] A Conversation with Douglas Hofstadter Immediate Past Chair Sonya Bahar…………….……………………………..…..2 Mark Spano [email protected] FEATURE Chair-Elect Mentoring: Raymond Goldstein A la carte is better than nothing [email protected] Kathy Barker………………………...……………..….8 Secretary/Treasurer Paul Gailey [email protected] See you in Austin! APS Councilor Robert Eisenberg [email protected] At-Large Members: Andrea Markelz [email protected] Leon Glass [email protected] Sergey Bezrukov [email protected] Lewis Rothberg [email protected] Ken Dill [email protected] Angel Garcia [email protected] Newsletter Editor Sonya Bahar [email protected] Website Coordinator Dan Gauthier [email protected] Jazz Scribble by Douglas Hofstadter See Page 2 1 An Eternal Golden Braid: A Conversation with Douglas Hofstadter Sonya Bahar proved to be inextricably folded into the very heart of mathematics, and also akin to the In 1980, recalls Douglas Hofstadter in the "loopy" processes that give rise to self- preface to the 20th-anniversary Edition of his replicating molecules, a familiar theme to classic work Gödel, Escher, Bach: an Eternal biophysicists. Golden Braid, “when GEB [Gödel, Escher, Bach] found itself for a while on the bestseller The key to the unraveling -

Brief Autobiographical Statement by Douglas Hofstadter • December, 2014

Brief Autobiographical Statement by Douglas Hofstadter • December, 2014 I was born in Manhattan in 1945, and spent the years 1947–1950 with my parents in Princeton, New Jersey. In 1950, our family moved to Stanford, California, where I grew up. We spent one year (1958–1959) in Geneva, Switzerland, which revolutionized my life, giving me a mastery of French and a love for other cultures and languages. I attended Stanford University in 1961–1965, receiving my B.S. with Distinction in mathematics. I obtained my Ph.D. in theoretical solid-state physics from the University of Oregon in 1975. I have held faculty positions at Indiana University, Bloomington (1977–1984 and 1988–present) and at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor (1984–1988). Today at Indiana University, I enjoy the honor of being called “College of Arts and Sciences Distinguished Professor of Cognitive Science and Comparative Literature”. As a math undergraduate at Stanford in the early 1960s, I explored many kinds of integer sequences, including a family that recently was dubbed “meta-Fibonacci recursions”, and which has been carefully studied by a handful of number-theorists around the world. A few years later in math graduate school at Berkeley, I was shocked to discover that I had hit my abstraction ceiling in math, and as a consequence, I wound up taking a pretty risky leap into particle physics at the University of Oregon in Eugene. After some five years of intense struggle in that area of physics, I bailed out in despair, this time riskily leaping to solid-state physics. -

Difficile Est Transferre Hanc Sententiam Latinam in Anglicam: the Depth and Charm

Difficile est transferre hanc sententiam Latinam in Anglicam: The Depth and Charm of Latin Translation February, 2006 Steven R. Perkins In 1950 British mathematician Alan Turing proposed a simple test to determine whether or not computers can think. Imagine you are seated at a computer that is connected to a computer in another room. Using the keyboard you enter various expressions and questions, and a person in the other room responds using the other computer and keyboard. Now consider what would happen if the other person exited the room, but a computer program were left to run in such a way that it continued the communication with you. Turing’s proposal was this: If you were unable to tell when the other person left and the computer program began to run, you would have to conclude that the computer could think. In other words, if the computer could fool you into believing you were communicating with a human being, we would have proof of a computer’s ability to think. Thirty years later philosopher John Searle attempted to undermine the Turing Test with his famous Chinese room experiment. Imagine you are locked in a room with a huge book of rules explaining in English how to respond in Chinese to a variety of Chinese sentences. Now suppose a native Chinese speaker slides slips of paper under your door containing sentences in Chinese. You look up the characters in your rule book, compose an answer in exact accordance to the rules, and slide your response back under the door. Unbeknownst to you, the sentences you received were actually questions, and the responses you wrote down, thanks to your rulebook but utterly unknown to you, were perfectly articulate responses.