Narrating Trauma in Contemporary Films About the Iraq War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coming-Of-Age Film in the Age of Activism

Coming-of-Age Film in the Age of Activism Agency and Intersectionality in Moonlight, Lady Bird, and Call Me By Your Name 29 – 06 – 2018 Supervisor: Anne Salden dr. M.A.M.B. (Marie) Lous Baronian [email protected] Second Reader: student number: 11927364 dr. A.M. (Abe) Geil Master Media Studies (Film Studies) University of Amsterdam Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank Marie Baronian for her first-rate supervision and constant support. Throughout this process she inspired and encouraged me, which is why she plays an important part in the completion of my thesis. I would also like to thank Veerle Spronck and Rosa Wevers, who proved that they are not only the best friends, but also the best academic proof-readers I could ever wish for. Lastly, I would like to express my gratitude towards my classmate and dear friend Moon van den Broek, who was always there for me when I needed advice (or just a hug) during these months, even though she had her own thesis to write too. Abstract The journey of ‘coming of age’ has been an inspiring human process for writers and filmmakers for centuries long, as its narrative format demonstrates great possibilities for both pedagogy and entertainment. The transformation from the origins of the genre, the German Bildungsroman, to classic coming-of-age cinema in the 1950s and 1980s in America saw few representational changes. Classic coming-of-age films relied heavily on the traditional Bildungsroman and its restrictive cultural norms of representation. However, in the present Age of Activism recent coming-of-age films seem to break with this tendency and broaden the portrayal of identity formation by incorporating diversity in its representations. -

Pulp Fiction © Jami Bernard the a List: the National Society of Film Critics’ 100 Essential Films, 2002

Pulp Fiction © Jami Bernard The A List: The National Society of Film Critics’ 100 Essential Films, 2002 When Quentin Tarantino traveled for the first time to Amsterdam and Paris, flush with the critical success of “Reservoir Dogs” and still piecing together the quilt of “Pulp Fiction,” he was tickled by the absence of any Quarter Pounders with Cheese on the European culinary scene, a casualty of the metric system. It was just the kind of thing that comes up among friends who are stoned or killing Harvey Keitel (left) and Quentin Tarantino attempt to resolve “The Bonnie Situation.” time. Later, when every nook and cranny Courtesy Library of Congress of “Pulp Fiction” had become quoted and quantified, this minor burger observation entered pop (something a new generation certainly related to through culture with a flourish as part of what fans call the video games, which are similarly structured). Travolta “Tarantinoverse.” gets to stare down Willis (whom he dismisses as “Punchy”), something that could only happen in a movie With its interlocking story structure, looping time frame, directed by an ardent fan of “Welcome Back Kotter.” In and electric jolts, “Pulp Fiction” uses the grammar of film each grouping, the alpha male is soon determined, and to explore the amusement park of the Tarantinoverse, a the scene involves appeasing him. (In the segment called stylized merging of the mundane with the unthinkable, “The Bonnie Situation,” for example, even the big crime all set in a 1970s time warp. Tarantino is the first of a boss is so inexplicably afraid of upsetting Bonnie, a night slacker generation to be idolized and deconstructed as nurse, that he sends in his top guy, played by Harvey Kei- much for his attitude, quirks, and knowledge of pop- tel, to keep from getting on her bad side.) culture arcana as for his output, which as of this writing has been Jack-Rabbit slim. -

Turtles Can Fly Won Glass Bear and Peace Film Award at the Berlin International Film Festival and the Golden Shell at the San Sebastian International Film Festival

Alice Hsu Agatha Pai Debby Lin Ellen Hsiao Jocelyn Lin Shirley Fang Tony Huang Xray Du Outline Introduction to the Director --Agatha Historical Background of the film –Ellen Main Argument Themes (4) The Mysterious Center (Debby), (1) Ironies (Tony), (2) US Invasion (Shirley) (3) Survival= Fly (Jocelyn) (5) Agrin Questions Agatha Pai Director Bahman Ghobadi ▸ Born on February 1, 1969 (age 42) in Baneh, Kurdistan Province. ▸ Receive a Bachelor of Arts in film directing from Iran Broadcasting College. ▸ Turtles Can Fly won Glass Bear and Peace Film Award at the Berlin International Film Festival and the Golden Shell at the San Sebastian International Film Festival. Turtles Can Fly ▸ Where did the story of the film come from and how did it take shape in your mind? ▸ With inexperienced children who had never acted before, how did you manage to write the dialogues? Ellen Hsiao Historical Background Kurdistan History: up to7th century ♦ c. 614 B.C.: Indo- European tribe came from Asia into the Iranian plateau ♦ 7th century: Conquered by Arabs many converted to Islam Kurdistan History: 7th – 19th ♦ Kurdistan is also occupied by: Seljuk Turks, the Mongols, the Safavid dynasty, and Ottoman Empire (13th century) ♦ 16th-19th: autonomous Kurdish principalities (ended with the collapse of Ottoman Empire) Kurdistan History: after WWI Treaty of Sevres (1920) ♦ It proposed an autonomous homeland for the Kurds ♦ Rich oil in Kurdistan Treaty of Sevres is rejected ♦ Oppression→ from the host countries Kurdish Inhabited Area Kurdish population mainly spread in: ♦ Turkey (12-14 million) ♦ Iran (7-10 million) ♦ Iraq (5-8 million) ♦ Syria (2-3 million) ♦ Armenia (50,000) Kurdistan ♦ Georgia (40,000) Operation Anfal (1986-1989) ♦ Genocide campaign against Kurdish people ♦ 4,500 villages destroyed ♦ 1.1 – 2.1 million death: 860,000 widows Greater number of orphans → → Halabja (Halabcheh) Massacre ♦ March 16, 1988: aka. -

Female Director Takes Hollywood by Storm: Is She a Beauty Or a Visionary?

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU Honors Senior Theses/Projects Student Scholarship 6-1-2016 Female Director Takes Hollywood by Storm: Is She a Beauty or a Visionary? Courtney Richardson Western Oregon University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/honors_theses Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation Richardson, Courtney, "Female Director Takes Hollywood by Storm: Is She a Beauty or a Visionary?" (2016). Honors Senior Theses/Projects. 107. https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/honors_theses/107 This Undergraduate Honors Thesis/Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Senior Theses/Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Female Director Takes Hollywood by Storm: Is She a Beauty or a Visionary? By Courtney Richardson An Honors Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation from the Western Oregon University Honors Program Dr. Shaun Huston, Thesis Advisor Dr. Gavin Keulks, Honors Program Director Western Oregon University June 2016 2 Acknowledgements First I would like to say a big thank you to my advisor Dr. Shaun Huston. He agreed to step in when my original advisor backed out suddenly and without telling me and really saved the day. Honestly, that was the most stressful part of the entire process and knowing that he was available if I needed his help was a great relief. Second, a thank you to my Honors advisor Dr. -

Brokeback and Outback

[CINEMA] ROKEBACK AND OUTBACK BRIAN MCFARLANE WELCOMES THE LATEST COMEBACK OF THE WESTERN IN TWO DISPARATE GUISES FROM time to time someone pronounces 'The Western is dead.' Most often, the only appropriate reply is 'Long live the Western!' for in the cinema's history of more than a century no genre has shown greater longevity or resilience. If it was not present at the birth of the movies, it was there shortly after the midwife left and, every time it has seemed headed for the doldrums, for instance in the late 1930s or the 1960s, someone—such as John Ford with Stagecoach (1939) or Sergio Leone and, later, Clint Eastwood—comes along and rescues it for art as well as box office. Western film historian and scholar Edward Buscombe, writing in The BFI Companion to the Western in 1988, not a prolific period for the Western, wrote: 'So far the genre has always managed to renew itself ... The Western may surprise us yet.' And so it is currently doing on our screens in two major inflections of the genre: the Australian/UK co-production, John Hillcoat's The Proposition, set in [65] BRIAN MCFARLANE outback Australia in the 1880s; and the US film, Ang Lee's Brokeback Mountain, set largely in Wyoming in 1963, lurching forwards to the 1980s. It was ever a char acteristic of the Western, and a truism of writing about it, that it reflected more about its time of production than of the period in which it was set, that it was a matter of America dreaming about its agrarian past. -

The Authentic Lessons of Schindler's List. INSTITUTION Research for Better Schools, Inc., Philadelphia, Pa

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 368 674 SO 023 998 AUTHOR Presseisen, Barbara Z.; Presseisen, Ernst L. TITLE The Authentic Lessons of Schindler's List. INSTITUTION Research for Better Schools, Inc., Philadelphia, Pa. SPONS AGENCY Office of Educational Research and Improvement (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE Feb 94 NOTE 22p. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Citizenship Education; Critical Thinking; Ethics; Films; *History Instruction; *Moral Values; *Nazism; Secondary Education; Social Studies; Teaching Methods; *World War II IDENTIFIERS Holocaust; *Schindler (Oskar); *Schindlers List ABSTRACT This document suggests that the movie "Schindler's List" be used as an instructional resource in order to provide criterion situations for teachings. The film opens multiple routes into complex questions that raise universal and immediate meanings, yet also generates idiosyncratic understanding. Learning history in an authentic way is more powerful than merely understanding the events of a particular story or even reading about them in a reputable textbook. Because of this, a teacher should strive to help students to begin to understand what the experience of history is and for what purpose it is included in the school curriculum. "Schindler's List" provides ample opportunities for students to raise questions about the world of the Third Reich. The important issue is that students need to be curious themselves, to raise the issues to be pursued, and to construct new meanings through their own work. At the same time, broader concerns of learning history need to be addressed through the goals of classroom instruction. The film provides opportunities to teach critical thinking and the pursuit of supportive argument. -

Using Data Science to Understand the Film Industry's Gender

Using Data Science to Understand the Film Industry's Gender Gap Dima Kagan∗1, Thomas Chesneyy2, and Michael Firez1 1Department of Software and Information Systems Engineering, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev 2Nottingham University Business School August 7, 2019 Abstract Data science can offer answers to a wide range of social science ques- tions. Here we turn attention to the portrayal of women in movies, an industry that has a significant influence on society, impacting such aspects of life as self-esteem and career choice. To this end, we fused data from the online movie database IMDb with a dataset of movie dialogue subti- tles to create the largest available corpus of movie social networks (15,540 networks). Analyzing this data, we investigated gender bias in on-screen female characters over the past century. We find a trend of improvement in all aspects of women`s roles in movies, including a constant rise in the centrality of female characters. There has also been an increase in the number of movies that pass the well-known Bechdel test, a popular|albeit flawed|measure of women in fiction. Here we propose a new and better alternative to this test for evaluating female roles in movies. Our study introduces fresh data, an open-code framework, and novel techniques that present new opportuni- ties in the research and analysis of movies. arXiv:1903.06469v3 [cs.SI] 6 Aug 2019 Keywords: Data Science, Network Science, Gender Gap, Social Networks 1 Introduction ∗[email protected] [email protected] zmickyfi@post.bgu.ac.il 1 2 The film industry is one of the strongest branches of the media, reaching billions of viewers worldwide [13, 19]. -

A Social Network Analysis of Coproduction Relationships in High Grossing Versus Highly Lauded Films in the U.S

International Journal of Communication 5 (2011), 1014–1033 1932–8036/20111014 Producing Quality: A Social Network Analysis of Coproduction Relationships in High Grossing Versus Highly Lauded Films in the U.S. Market JADE L. MILLER Tulane University While mainstream U.S. film production has been derided as following a “lowest common denominator” blockbuster-style logic, the industry has actually produced both popular and highly regarded productions. To imagine an alternative (lower cost, higher quality) Hollywood of the future, this article set out to examine the network structure of coproductions in both high grossing and in highly lauded films in the U.S. market for a recent five-year period. Using social network analysis, this study shows that the funding structures of both types of films were less centralized, dense, and clustered than is commonly believed. Coproduction networks of highly lauded films, however, did exhibit structural differences from their high grossing counterparts that suggest more collaboration and penetrability. If the future of film production looks like the structures of the alternative Hollywood described here, we may see a more cooperative, dispersed, and international industrial structure for the future. If one looks at the funding structure of most films released in American theaters, a pattern of familiar names quickly emerges: Paramount, Universal, MGM, and those of other major movie studios. It’s no secret that the majority of films that achieve mass domestic (and international) promotion and distribution are usually associated with a small elite: an oligarchy of production and distribution, headed by a small group of risk-adverse and notoriously nervous executives. -

Rocky (1976) Movie Script by Sylvester Stallone

Rocky (1976) movie script by Sylvester Stallone. Final draft, 1/7/76. More info about this movie on IMDb.com INT. BLUE DOOR FIGHT CLUB - NIGHT SUPERIMPOSE OVER ACTION... "NOVEMBER 12, 1975 - PHILADELPHIA" ... The club itself resembles a large unemptied trash-can. The boxing ring is extra small to insure constant battle. The lights overhead have barely enough wattage to see who is fighting. In the ring are two heavyweights, one white the other black. The white fighter is ROCKY BALBOA. He is thirty years old. His face is scarred and thick around the nose... His black hair shines and hangs in his eyes. Rocky fights in a plodding, machine-like style. The BLACK FIGHTER dances and bangs combinations into Rocky's face with great accuracy. But the punches do not even cause Rocky to blink... He grins at his opponent and keeps grinding ahead. The people at ringside sit on folding chairs and clamor for blood... They lean out of their seats and heckle the fighters. In the thick smoke they resemble spectres. Everyone is hustling bets... The action is even heavier in the balcony. A housewife yells for somebody to cover a two dollar bet. The BELL RINGS and the fighters return to their corner... Somebody heaves a beer can into the ring. The Black Fighter spits something red in a bucket and sneers across the ring at Rocky. BLACK FIGHTER (to cornerman) ... I'm gonna bust his head wide open! In Rocky's corner he is being assisted by a shriveled, balding CORNERMAN, who is an employee of the club.. -

Teaching Social Studies Through Film

Teaching Social Studies Through Film Written, Produced, and Directed by John Burkowski Jr. Xose Manuel Alvarino Social Studies Teacher Social Studies Teacher Miami-Dade County Miami-Dade County Academy for Advanced Academics at Hialeah Gardens Middle School Florida International University 11690 NW 92 Ave 11200 SW 8 St. Hialeah Gardens, FL 33018 VH130 Telephone: 305-817-0017 Miami, FL 33199 E-mail: [email protected] Telephone: 305-348-7043 E-mail: [email protected] For information concerning IMPACT II opportunities, Adapter and Disseminator grants, please contact: The Education Fund 305-892-5099, Ext. 18 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.educationfund.org - 1 - INTRODUCTION Students are entertained and acquire knowledge through images; Internet, television, and films are examples. Though the printed word is essential in learning, educators have been taking notice of the new visual and oratory stimuli and incorporated them into classroom teaching. The purpose of this idea packet is to further introduce teacher colleagues to this methodology and share a compilation of films which may be easily implemented in secondary social studies instruction. Though this project focuses in grades 6-12 social studies we believe that media should be infused into all K-12 subject areas, from language arts, math, and foreign languages, to science, the arts, physical education, and more. In this day and age, students have become accustomed to acquiring knowledge through mediums such as television and movies. Though books and text are essential in learning, teachers should take notice of the new visual stimuli. Films are familiar in the everyday lives of students. -

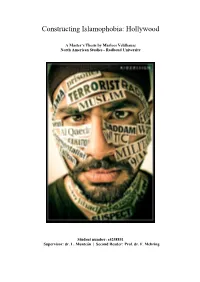

Constructing Islamophobia: Hollywood

Constructing Islamophobia: Hollywood A Master’s Thesis by Marloes Veldhausz North American Studies - Radboud University Student number: s4258851 Supervisor: dr. L. Munteán | Second Reader: Prof. dr. F. Mehring Veldhausz 4258851/2 Abstract Islam has become highly politicized post-9/11, the Islamophobia that has followed has been spread throughout the news media and Hollywood in particular. By using theories based on stereotypes, Othering, and Orientalism and a methodology based on film studies, in particular mise-en-scène, the way in which Islamophobia has been constructed in three case studies has been examined. These case studies are the following three Hollywood movies: The Hurt Locker, Zero Dark Thirty, and American Sniper. Derogatory rhetoric and mise-en-scène aspects proved to be shaping Islamophobia. The movies focus on events that happened post- 9/11 and the ideological markers that trigger Islamophobia in these movies are thus related to the opinions on Islam that have become widespread throughout Hollywood and the media since; examples being that Muslims are non-compatible with Western societies, savages, evil, and terrorists. Keywords: Islam, Muslim, Arab, Islamophobia, Religion, Mass Media, Movies, Hollywood, The Hurt Locker, Zero Dark Thirty, American Sniper, Mise-en-scène, Film Studies, American Studies. 2 Veldhausz 4258851/3 To my grandparents, I can never thank you enough for introducing me to Harry Potter and thus bringing magic into my life. 3 Veldhausz 4258851/4 Acknowledgements Thank you, first and foremost, to dr. László Munteán, for guiding me throughout the process of writing the largest piece of research I have ever written. I would not have been able to complete this daunting task without your help, ideas, patience, and guidance. -

The Impact of Social Media on a Movie's Financial Performance

Undergraduate Economic Review Volume 9 Issue 1 Article 10 2012 Turning Followers into Dollars: The Impact of Social Media on a Movie’s Financial Performance Joshua J. Kaplan State University of New York at Geneseo, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/uer Part of the Economics Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Kaplan, Joshua J. (2012) "Turning Followers into Dollars: The Impact of Social Media on a Movie’s Financial Performance," Undergraduate Economic Review: Vol. 9 : Iss. 1 , Article 10. Available at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/uer/vol9/iss1/10 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Commons @ IWU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this material in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This material has been accepted for inclusion by faculty at Illinois Wesleyan University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©Copyright is owned by the author of this document. Turning Followers into Dollars: The Impact of Social Media on a Movie’s Financial Performance Abstract This paper examines the impact of social media, specifically witterT , on the domestic gross box office revenue of 207 films released in the United States between 2009 and 2011.