Etowah River Ocmulgee River Little Lotts Creek

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stream-Temperature Characteristics in Georgia

STREAM-TEMPERATURE CHARACTERISTICS IN GEORGIA By T.R. Dyar and S.J. Alhadeff ______________________________________________________________________________ U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 96-4203 Prepared in cooperation with GEORGIA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION DIVISION Atlanta, Georgia 1997 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Charles G. Groat, Director For additional information write to: Copies of this report can be purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Branch of Information Services 3039 Amwiler Road, Suite 130 Denver Federal Center Peachtree Business Center Box 25286 Atlanta, GA 30360-2824 Denver, CO 80225-0286 CONTENTS Page Abstract . 1 Introduction . 1 Purpose and scope . 2 Previous investigations. 2 Station-identification system . 3 Stream-temperature data . 3 Long-term stream-temperature characteristics. 6 Natural stream-temperature characteristics . 7 Regression analysis . 7 Harmonic mean coefficient . 7 Amplitude coefficient. 10 Phase coefficient . 13 Statewide harmonic equation . 13 Examples of estimating natural stream-temperature characteristics . 15 Panther Creek . 15 West Armuchee Creek . 15 Alcovy River . 18 Altamaha River . 18 Summary of stream-temperature characteristics by river basin . 19 Savannah River basin . 19 Ogeechee River basin. 25 Altamaha River basin. 25 Satilla-St Marys River basins. 26 Suwannee-Ochlockonee River basins . 27 Chattahoochee River basin. 27 Flint River basin. 28 Coosa River basin. 29 Tennessee River basin . 31 Selected references. 31 Tabular data . 33 Graphs showing harmonic stream-temperature curves of observed data and statewide harmonic equation for selected stations, figures 14-211 . 51 iii ILLUSTRATIONS Page Figure 1. Map showing locations of 198 periodic and 22 daily stream-temperature stations, major river basins, and physiographic provinces in Georgia. -

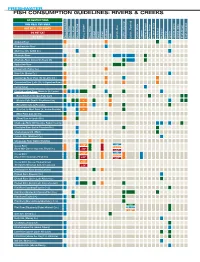

Fish Consumption Guidelines: Rivers & Creeks

FRESHWATER FISH CONSUMPTION GUIDELINES: RIVERS & CREEKS NO RESTRICTIONS ONE MEAL PER WEEK ONE MEAL PER MONTH DO NOT EAT NO DATA Bass, LargemouthBass, Other Bass, Shoal Bass, Spotted Bass, Striped Bass, White Bass, Bluegill Bowfin Buffalo Bullhead Carp Catfish, Blue Catfish, Channel Catfish,Flathead Catfish, White Crappie StripedMullet, Perch, Yellow Chain Pickerel, Redbreast Redhorse Redear Sucker Green Sunfish, Sunfish, Other Brown Trout, Rainbow Trout, Alapaha River Alapahoochee River Allatoona Crk. (Cobb Co.) Altamaha River Altamaha River (below US Route 25) Apalachee River Beaver Crk. (Taylor Co.) Brier Crk. (Burke Co.) Canoochee River (Hwy 192 to Ogeechee River) Chattahoochee River (Helen to Lk. Lanier) (Buford Dam to Morgan Falls Dam) (Morgan Falls Dam to Peachtree Crk.) * (Peachtree Crk. to Pea Crk.) * (Pea Crk. to West Point Lk., below Franklin) * (West Point dam to I-85) (Oliver Dam to Upatoi Crk.) Chattooga River (NE Georgia, Rabun County) Chestatee River (below Tesnatee Riv.) Conasauga River (below Stateline) Coosa River (River Mile Zero to Hwy 100, Floyd Co.) Coosa River <32" (Hwy 100 to Stateline, Floyd Co.) >32" Coosa River (Coosa, Etowah below Thompson-Weinman dam, Oostanaula) Coosawattee River (below Carters) Etowah River (Dawson Co.) Etowah River (above Lake Allatoona) Etowah River (below Lake Allatoona dam) Flint River (Spalding/Fayette Cos.) Flint River (Meriwether/Upson/Pike Cos.) Flint River (Taylor Co.) Flint River (Macon/Dooly/Worth/Lee Cos.) <16" Flint River (Dougherty/Baker Mitchell Cos.) 16–30" >30" Gum Crk. (Crisp Co.) Holly Crk. (Murray Co.) Ichawaynochaway Crk. Kinchafoonee Crk. (above Albany) Little River (above Clarks Hill Lake) Little River (above Ga. Hwy 133, Valdosta) Mill Crk. -

Ogeechee River

I ) f'"I --- , ',, ', ' • ''i' • ;- 1, '\::'.e...,. " .; IL. r final wild and s~;ni;ri~~f'1tu~; MAY, 1984 OGEECHEE RIVER GEORGIA L_ - UNITED STATES DEPARI'MENT OF 'IHE INTERIOR/NATIONAL PARK SERVICE As the Nation's principal conservation a gency, the Department of the Interior has responsibility tor most of our nationally owned public lands and natural resources. This includes fostering the wisest use of our land and water resources, protecting our fish and wildlife, preserving the environ mental and cultural values of our national parks and historical places, and providing for the enjoyment of life through out door recreation. The Department assesses our energy and min eral resources and works to assure that their development is • in the best interests of all our people. The Department also has a major responsibility for American Indian reservation communities and for people who live in island territories un der U. S. administration. f Pf /p- I. SUMMARY OF FINDIN:jS / 1 II. CONDUCT OF 'ffiE STUDY / 5 Backgrouoo and Purpose of Study I 5 Study Approach I 5 Public Involvement I 6 III. EVALUATICN / 8 Eligibility I 8 Classification I 8 Suitability I 11 IV. THE RIVER ENVIOC>NMENT / 17 I.ocation and Access / 17 Population I 17 Landownership and Use I 17 Natural Resources / 22 Recreation Resources I 32 Cultural Resources I 35 V. A GUIDE 'IO RIVER PIDTECTICN ALTERNATIVES / 37 VI. LIST OF STUDY PARI'ICIPANI'S AND CXNSULTANI'S / 52 VII. APPENDIX / 54 IWJSTRATIONS/rABLES I.ocation Map I 3 River Classification / 9 Ogeechee River Study Region County Populations / 18 General Land Uses / 19 Typical Ogeechee River Sections Lower Piedmont Segment I 23 Upper Coastal Plain Segment I 24 Lower Coastal Plain / 25 Coastal Marsh I 26 Hydrology I 29 Significant Features I 33 Line-of-Sight Fran the River / 42 I. -

Chemical Character of Surface Waters of Georgia

SliEU' :\0..... / ........ RO O ~ l NO. ···- ··-<~ ......... U )'On no l~er need this publication write to the Geological Sur»ey in Washlndon for ali official maillne label to use In returning it UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR CHEMICAL CHARACTER OF SURFACE WATERS OF GEORGIA Prepared In cooperation wilh the DIVISION OF MINES, MINING, AND GEOLOGY OF 'l'HE GEORGIA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 889- E ' UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Harold L. Ickes, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. E. Wrather, Director Water-Supply Paper 889-E CHEMICAL CHARACTER OF SURFACE WATERS OF GEORGIA BY WILLIAM L. LAMAR Prepared in cooperation with the DIVISION OF MINES, MINING, AND GEOLOGY OF THE GEORGIA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Contributions to the Hydrology of the United States, 19~1-!3 (Pages 317- 380) UN ITED STATES GOVEHNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1944 For sct le Ly Ll w S upcrinkntlent of Doc uments, U. S. Gover nme nt Printing Office, " ' asbingtou 25, D . C. Price 15 ce nl~ CONTENTS Page- Abstract ___________________________________________ -----_--------- 31 T Introduction __________________ c ________________________________ -- _ 317 Physiography_____________________________________________________ 318 Climate__________________________________________________________ 820 Collection and examination of samples_______________________________ 323 Stream flow __________________________ --------- ___________ c ________ . 324 Rainfall and discharge during sampling years_____________________ -

Lloyd Shoals

Southern Company Generation. 241 Ralph McGill Boulevard, NE BIN 10193 Atlanta, GA 30308-3374 404 506 7219 tel July 3, 2018 FERC Project No. 2336 Lloyd Shoals Project Notice of Intent to Relicense Lloyd Shoals Dam, Preliminary Application Document, Request for Designation under Section 7 of the Endangered Species Act and Request for Authorization to Initiate Consultation under Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act Ms. Kimberly D. Bose, Secretary Federal Energy Regulatory Commission 888 First Street, N.E. Washington, D.C. 20426 Dear Ms. Bose: On behalf of Georgia Power Company, Southern Company is filing this letter to indicate our intent to relicense the Lloyd Shoals Hydroelectric Project, FERC Project No. 2336 (Lloyd Shoals Project). We will file a complete application for a new license for Lloyd Shoals Project utilizing the Integrated Licensing Process (ILP) in accordance with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission’s (Commission) regulations found at 18 CFR Part 5. The proposed Process, Plan and Schedule for the ILP proceeding is provided in Table 1 of the Preliminary Application Document included with this filing. We are also requesting through this filing designation as the Commission’s non-federal representative for consultation under Section 7 of the Endangered Species Act and authorization to initiate consultation under Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act. There are four components to this filing: 1) Cover Letter (Public) 2) Notification of Intent (Public) 3) Preliminary Application Document (Public) 4) Preliminary Application Document – Appendix C (CEII) If you require further information, please contact me at 404.506.7219. Sincerely, Courtenay R. -

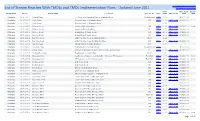

List of TMDL Implementation Plans with Tmdls Organized by Basin

Latest 305(b)/303(d) List of Streams List of Stream Reaches With TMDLs and TMDL Implementation Plans - Updated June 2011 Total Maximum Daily Loadings TMDL TMDL PLAN DELIST BASIN NAME HUC10 REACH NAME LOCATION VIOLATIONS TMDL YEAR TMDL PLAN YEAR YEAR Altamaha 0307010601 Bullard Creek ~0.25 mi u/s Altamaha Road to Altamaha River Bio(sediment) TMDL 2007 09/30/2009 Altamaha 0307010601 Cobb Creek Oconee Creek to Altamaha River DO TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010601 Cobb Creek Oconee Creek to Altamaha River FC 2012 Altamaha 0307010601 Milligan Creek Uvalda to Altamaha River DO TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 2006 Altamaha 0307010601 Milligan Creek Uvalda to Altamaha River FC TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010601 Oconee Creek Headwaters to Cobb Creek DO TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010601 Oconee Creek Headwaters to Cobb Creek FC TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010602 Ten Mile Creek Little Ten Mile Creek to Altamaha River Bio F 2012 Altamaha 0307010602 Ten Mile Creek Little Ten Mile Creek to Altamaha River DO TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010603 Beards Creek Spring Branch to Altamaha River Bio F 2012 Altamaha 0307010603 Five Mile Creek Headwaters to Altamaha River Bio(sediment) TMDL 2007 09/30/2009 Altamaha 0307010603 Goose Creek U/S Rd. S1922(Walton Griffis Rd.) to Little Goose Creek FC TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010603 Mushmelon Creek Headwaters to Delbos Bay Bio F 2012 Altamaha 0307010604 Altamaha River Confluence of Oconee and Ocmulgee Rivers to ITT Rayonier -

Report (ADR), (U.S

Summary of Hydrologic Conditions in Georgia, 2008 The United States Geological and new historic minimum flows were Survey (USGS) Georgia Water Science recorded at several streamgages with Center (WSC) maintains a long-term 20 or more years of record. New historic hydrologic monitoring network of more low water levels were recorded in some than 290 real-time streamgages, more of Georgia’s confined and unconfined than 170 groundwater wells, and 10 lake aquifers, and many recorded water levels and reservoir monitoring stations. One of were below the historic median. Several the many benefits of data collected from lake and reservoir water levels were well this monitoring network is that analysis below average and continued to decline as of the data provides an overview of the the end of the 2008 WY approached. hydrologic conditions of rivers, creeks, Historically, droughts in Georgia Lake Sidney Lanier, Georgia. Photo by Brian E. McCallum, USGS, February 2008. reservoirs, and aquifers in Georgia. typically have lasted between 2 and Hydrologic conditions are determined 5 years. The latest drought began in spring by statistical analysis of data collected 2006. Georgia’s Drought Level One Local governments asked residents to limit during the current water year1 (WY) and through Four are issued by the Georgia showers to 5 minutes or less, reuse clean comparison of the results to historical data Environmental Protection Division household water, and install low-flow collected at long-term stations. During (Regan and Cash, 2009). The drought toilets, faucets, and showerheads, if the drought that persisted through 2008, levels implement water saving techniques possible, in older homes (City of Union the USGS succeeded in verifying and with Level One Drought being the least City, 2008). -

The Georgia Coast Saltwater Paddle Trail

2010 The Georgia Coast Saltwater Paddle Trail This project was funded in part by the Coastal Management Program of the Georgia Department of Natural Resources, and the U.S. Department of Commerce, Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management (OCRM), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) grant award #NA09NOS4190171, as well as the National Park Service Rivers, Trails & Conservation Assistance Program. The statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of OCRM or NOAA. September 30, 2010 0 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ......................................................................................................................................... 2 Coastal Georgia Regional Development Center Project Team .......................................................... 3 Planning and Government Services Staff ................................................................................................... 3 Geographic Information Systems Staff ....................................................................................................... 3 Economic Development Staff .......................................................................................................................... 3 Administrative Services Staff .......................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................... -

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Regulatory Program in Georgia

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Regulatory Program in Georgia David Lekson, PWS Kelly Finch, PWS Richard Morgan Savannah District August, 2013 US Army Corps of Engineers BUILDING STRONG® Topics § Savannah District Regulatory Division § Regulatory Efficiencies § On the Horizon 2 BUILDING STRONG® Introduction § Joined Savannah District in Jan 2013 § 25 years as Branch Chief in the Wilmington District, NC § Certified Professional Wetland Scientist with extensive field and teaching experience across the country § Participated in regional and national initiatives (wetland delineation and assessment, Mitigation/Banking); Served 6- month detail at the Pentagon in 2012 § Evaluated phosphate/sand/rock mining, wind energy, port and military projects, water supply, landfills, utilities, transportation (highway, airport, rail), and other large-scale commercial and residential projects 3 BUILDING STRONG® Georgia § Largest state east of the Mississippi River TN NC § 59,425 Square miles § Abuts 5 states § 5 Ecoregions SC § 159 Counties AL § 70,000 Miles of waterways § 7.7 Million acres of wetlands FL 4 BUILDING STRONG® Savannah Regulatory Organization Lake Lanier Piedmont Branch Mr. Ed Johnson (678) 422-2722 Morrow Coastal Branch Ms. Kelly Finch (912) 652-5503 Savannah Albany § 35 Team members § 3 Field Offices & Savannah § 3 Branches (Piedmont, Coastal, Multipurpose Management) 5 BUILDING STRONG® Regulatory Efficiencies § General Permits ► Re-issuance of existing Regional and Programmatic General Permits ► New RGP37 for Inshore GADNR Artificial Reefs -

WATERING GEORGIA: the State of Water and Agriculture in Georgia

WATERING GEORGIA: The State of Water and Agriculture in Georgia A Report by the Georgia Water Coalition | November 2017 About the Georgia Water Coalition Founded in 2002, the Georgia Water Coalition’s (GWC) mission is to protect and care for Georgia’s surface water and groundwater resources, which are essential for sustaining economic prosperity, providing clean and abundant drinking water, preserving diverse aquatic habitats for wildlife and recreation, strengthening property values, and protecting the quality of life for current and future generations. The GWC is a group of more than 240 organizations representing well over a quarter of a million Georgians including farmers, homeowner and lake associations, business owners, sportsmen’s clubs, conservation organizations, professional associations and religious groups who work collaboratively and transparently with each other to achieve specific conservation goals. About Chattahoochee Riverkeeper, Inc. Chattahoochee Riverkeeper’s (CRK) mission is to advocate and secure the protection and stewardship of the Chattahoochee River, including its lakes, tributaries and watershed, in order to restore and conserve their ecological health for the people and wildlife that depend on the river system. Established in 1994, CRK is an environmental advocacy education organization with more than 7,300 members dedicated solely to protecting and restoring the Chattahoochee River Basin. CRK was the 11th licensed program in the international Waterkeeper Alliance, now more than 300 organizations strong. CRK is also a founding member of the GWC. Acknowledgements We wish to thank the C. S. Mott Foundation for its support of this project. Additionally, Gordon Rogers (Flint Riverkeeper) Written by Dr. Chris Manganiello- provided assistance throughout this project. -

Streamflow Maps of Georgia's Major Rivers

GEORGIA STATE DIVISION OF CONSERVATION DEPARTMENT OF MINES, MINING AND GEOLOGY GARLAND PEYTON, Director THE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Information Circular 21 STREAMFLOW MAPS OF GEORGIA'S MAJOR RIVERS by M. T. Thomson United States Geological Survey Prepared cooperatively by the Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior, Washington, D. C. ATLANTA 1960 STREAMFLOW MAPS OF GEORGIA'S MAJOR RIVERS by M. T. Thomson Maps are commonly used to show the approximate rates of flow at all localities along the river systems. In addition to average flow, this collection of streamflow maps of Georgia's major rivers shows features such as low flows, flood flows, storage requirements, water power, the effects of storage reservoirs and power operations, and some comparisons of streamflows in different parts of the State. Most of the information shown on the streamflow maps was taken from "The Availability and use of Water in Georgia" by M. T. Thomson, S. M. Herrick, Eugene Brown, and others pub lished as Bulletin No. 65 in December 1956 by the Georgia Department of Mines, Mining and Geo logy. The average flows reported in that publication and sho\vn on these maps were for the years 1937-1955. That publication should be consulted for detailed information. More recent streamflow information may be obtained from the Atlanta District Office of the Surface Water Branch, Water Resources Division, U. S. Geological Survey, 805 Peachtree Street, N.E., Room 609, Atlanta 8, Georgia. In order to show the streamflows and other features clearly, the river locations are distorted slightly, their lengths are not to scale, and some features are shown by block-like patterns. -

Fish Consumption Guidelines: Rivers & Creeks

FRESHWATER FISH CONSUMPTION GUIDELINES: RIVERS & CREEKS NO RESTRICTIONS ONE MEAL PER WEEK ONE MEAL PER MONTH DO NOT EAT NO DATA Bass, LargemouthBass, Other Bass, Shoal Bass, Spotted Bass, Striped Bass, White Bass, Bluegill Bowfin Buffalo Bullhead Carp Catfish, Blue Catfish, Channel Catfish,Flathead Catfish, White Crappie StripedMullet, Perch, Yellow Chain Pickerel, Redbreast Redhorse Redear Sucker Green Sunfish, Sunfish, Other Brown Trout, Rainbow Trout, Alapaha River Alapahoochee River Allatoona Crk. (Cobb Co.) Altamaha River Altamaha River (below US Route 25) Apalachee River Beaver Crk. (Taylor Co.) Brier Crk. (Burke Co.) Canoochee River (Hwy 192 to Lotts Crk.) Canoochee River (Lotts Crk. to Ogeechee River) Casey Canal Chattahoochee River (Helen to Lk. Lanier) (Buford Dam to Morgan Falls Dam) (Morgan Falls Dam to Peachtree Crk.) * (Peachtree Crk. to Pea Crk.) * (Pea Crk. to West Point Lk., below Franklin) * (West Point dam to I-85) (Oliver Dam to Upatoi Crk.) Chattooga River (NE Georgia, Rabun County) Chestatee River (below Tesnatee Riv.) Chickamauga Crk. (West) Cohulla Crk. (Whitfield Co.) Conasauga River (below Stateline) <18" Coosa River <20" 18 –32" (River Mile Zero to Hwy 100, Floyd Co.) ≥20" >32" <18" Coosa River <20" 18 –32" (Hwy 100 to Stateline, Floyd Co.) ≥20" >32" Coosa River (Coosa, Etowah below <20" Thompson-Weinman dam, Oostanaula) ≥20" Coosawattee River (below Carters) Etowah River (Dawson Co.) Etowah River (above Lake Allatoona) Etowah River (below Lake Allatoona dam) Flint River (Spalding/Fayette Cos.) Flint River (Meriwether/Upson/Pike Cos.) Flint River (Taylor Co.) Flint River (Macon/Dooly/Worth/Lee Cos.) <16" Flint River (Dougherty/Baker Mitchell Cos.) 16–30" >30" Gum Crk.