Dynamic Pricing for the Lion King

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Keybank Broadway at the Paramount and Seattle Theatre Group Announce the 2013/2014 Season Of

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE FEBRUARY 18, 2013 Media Contacts: Julie Furlong, Furlong Communications, Inc., 206.850.9448, [email protected] Antonio Hicks, Seattle Theatre Group, 206.315.8016, [email protected] KeyBank Broadway at The Paramount and Seattle Theatre Group Announce The 2013/2014 Season of SEATTLE – The 2013/2014 KeyBank Broadway at The Paramount Season will bring another year of unforgettable entertainment to The Paramount Theatre, with a roster of Broadway blockbusters and some venerable favorites. The 2013/2014 Season starts with the magical and enchanting THE WIZARD OF OZ, followed by PRISCILLA QUEEN OF THE DESERT, the joyously fun show featuring a trio of friends on a journey in search of love and friendship. The season continues with all time favorites EVITA and Disney’s THE LION KING and finally culminates with eight time Tony Award® winner, ONCE, about a Dublin street musician who’s about to give up his dream when a beautiful young woman takes a sudden interest in his haunting love songs. For more information, please visit, www.stgpresents.org/Broadway. The line up for the 2013/2014 KeyBank Broadway at The Paramount Season is as follows: THE WIZARD OF OZ October 9-13, 2013 PRISCILLA QUEEN OF THE DESERT November 12-17, 2013 EVITA December 31, 2013-January 5, 2014 Disney’s THE LION KING March 11-April 6, 2014 ONCE May 27-June 8, 2014 The 2013/2014 Season THE WIZARD OF OZ October 9-13, 2013 “We’re off to see….” The most magical adventure of them all. Andrew Lloyd Webber’s new production of The Wizard of Oz is an enchanting adaptation of the all-time classic, totally reconceived for the stage by the award-winning creative team that recently delighted London and Toronto audiences with the revival of The Sound of Music. -

Thebestarts.Com Presents “The Lion Sings Tonight” a Cabaret

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Kevin Ireland, theBestArts.com – Atlanta benefit presenter http://www.thebestarts.com/lionkingbenefitpresskit/ 678-638-4301 email: [email protected] Jerry Henderson, Joining Hearts – Marketing Manager 404-216-8794 email: [email protected] Jennifer Walker, Broadway in Atlanta – BRAVE Public Relations 404-233-3993 e-mail: [email protected] theBestArts.com presents “The Lion Sings Tonight” A cabaret featuring cast members from DISNEY’S THE LION KING Monday, April 21, 2014, at 7:30pm Rich Theatre – Woodruff Arts Center – 1280 Peachtree Street, Atlanta to benefit Joining Hearts and Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS On Monday, April 21st at 7:30pm, theBestArts.com will present its fifth Broadway benefit cabaret in Atlanta, THE LION SINGS TONIGHT. The evening will feature performances by cast and crew members of the Broadway national touring company of DISNEY’S THE LION KING at the Woodruff Arts Center’s Rich Theatre in midtown Atlanta. 100% of ticket revenue from this event will go directly to JOINING HEARTS and BROADWAY CARES/EQUITY FIGHTS AIDS (BC/EFA). Produced by Kevin Ireland, founder of theBestArts.com, along with DISNEY’S THE LION KING company members Ben Lipitz and Jelani Remy, the evening will have audience members Dancing In Their Seats to top 60s hits from Aretha Franklin, the Supremes, Marvin Gaye, the Temptations, the Rolling Stones, Gladys Knight and many more. Over 25 singers, dancers and musicians from the company will showcase their diverse singing and dance talents, accompanied by a live band. A mid-show auction will present opportunities to join the company backstage at THE FOX THEATRE and a June trip to NYC to attend the Broadway show of your choice AND Broadway Bares. -

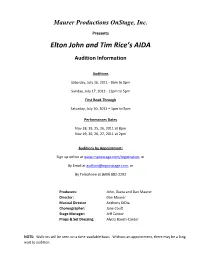

Elton John and Tim Rice's AIDA

Maurer Productions OnStage, Inc. Presents Elton John and Tim Rice’s AIDA Audition Information Auditions Saturday, July 16, 2011 - 9am to 5pm Sunday, July 17, 2011 - 12pm to 5pm First Read-Through Saturday, July 30, 2011 – 1pm to 5pm Performances Dates Nov 18, 19, 25, 26, 2011 at 8pm Nov 19, 20, 26, 27, 2011 at 2pm Auditions by Appointment: Sign up online at www.mponstage.com/registration, or By Email at [email protected], or By Telephone at (609) 882-2292 Producers: John, Diana and Dan Maurer Director: Dan Maurer Musical Director Anthony DiDia Choreographer: Jane Coult Stage Manager: Jeff Cantor Props & Set Dressing: Alycia Bauch-Cantor NOTE: Walk-ins will be seen on a time-available basis. Without an appointment, there may be a long wait to audition. Auditions for Elton John & Tim Rice’s AIDA Index 1. About the Show 2. Available Roles 3. What You Need to Know About the Audition 4. Audition Application 5. Calendar for Conflicts 6. Musical Numbers 7. Audition Monologues 1 Elton John and Tim Rice’s Aida Directed by Dan Maurer Part Broadway musical, part dance spectacular and part rock concert, AIDA is an epic tale about the power and timelessness of love. The show features over twenty roles for singers, dancers, and actors of various races and will be staged by the award winning production team that brought shows like Man of La Mancha and Singin’ in the Rain to Kelsey Theatre. Winner of four Tony Awards when Disney’s Hyperion Theatrical Group first brought it to Broadway, AIDA features music by pop legend Elton John and lyrics by Tim Rice, who wrote the lyrics for hit shows like Jesus Christ Superstar and Evita. -

BROADWAY at KENT KENT Community Friday, June 15, 2018 • 1:30 - 3 P.M

BACK BY POPULAR REQUEST! SEATTLE THEATRE GROUP IN PARTNERSHIP WITH THE KENT SENIOR ACTIVITY CENTER BRING BACK: STG'S BROADWAY AT KENT KENT Community Friday, June 15, 2018 • 1:30 - 3 p.m. Kent Senior Activity Center, Social Hall EVENT 600 E. Smith Street, Kent, WA $5.00 all ages 14+ • Advanced Pre-registration required (253) 856-5150 • Class #65920 STG's Broadway at Kent is a new dance program presented by Seattle Theatre Group and the Kent Senior Activity Center. Participants are invited to take classes inspired by Broadway shows being presented at the Paramount Theatre. Please note, this class is not taught by a Color Purple company member. Broadway at Kent is taught by local Seattle dance choreographer Nikki Long. Registrants who participate must sign a registration form before class begins. All who complete the workshop may receive information on how to receive a discount on tickets for the Paramount Theatre's Production of The Color Purple, opening June 27 in Seattle. Nikki Long is a The Lion King on Broadway and in its 1st National Tour, California native Monty Python's Spamalot 1st National Tour (original cast), who has lived and and a Radio City Rockette in NYC. Her regional theater danced all over the credits include Elf, Cinderella, Catch Me If You Can, On country and the world. The Town, White Christmas, Joseph and the Amazing She is a mother of Technicolor Dreamcoat, and Mame. She is a former two, a professional dancer for Gloria Estefan, Toni Braxton, and Monica. Other dancer, a professional highlights include performances on The Tony Awards, photographer, a Pilates Good Morning America, The View, The American Music instructor & assists in Awards, The Image Awards, The Today Show, Regis & the casting of Aladdin Kelly, 106 & Park, Nightline and various music videos and on Broadway & its commercials. -

The Community Band of Brevard Big Bands and Broadway

The Community Band of Brevard Presents Big Bands and Broadway Friday, June 4, 1999 at 8:00 P.M. Fine Arts Auditorium Brevard Community College, Cocoa Sunday, June 6, 1999 at 3:00 P.M. Auditorium Merritt Island High School Featuring Barbara Ziegler, vocalist and A Big Band Orchestra of Professional Performers 1 Purpose and History The Community Band of Brevard exists to educate its members, to entertain its audiences, and to serve its community. Specifically, For members, The Community Band of Brevard will provide: Enjoyable and meaningful music experiences; Opportunities to utilize their music performing skills and broaden their music horizons; Opportunities to develop and improve their performing skills both as individuals and as an ensemble. For audiences, The Community Band of Brevard will provide entertaining concerts of music performed at the highest level of quality. For the community, The Community Band of Brevard will provide its services, schedule permitting, when requested to satisfy the needs of the entire or significant subsets of the community. The musical director of the Community Band of Brevard is Mr. Marion Scott, Director of Bands at Bre- vard Community College. Mr. Scott formed the Community Band of Brevard in 1985 to provide a per- formance outlet for adult musicians in the area. The Band’s membership, currently numbering about sixty, includes people of all ages representing many occupations. The Community Band of Brevard takes seriously its responsibility to provide entertaining concerts at the highest level of quality. That has always been our goal, but in June, 1992 the Band’s members formally committed to Philosophy, Purpose, and Vision statements which succinctly describe the operating princi- ples governing the Band's decisions and processes and which have produced a high quality ensemble. -

We're Still Here.Adults

Pax Amicus Castle Theatre is Alive and Well in Budd Lake “We’re Still Here” A Musical Theatre Celebration in the Garden For the Adults, their Partners, Mates and Friends Hosted by Stan Barber and Rich Boyer REBECCA BERES MATTHEW GANDOLFO MARIANNE KERR Star of “The King and I” and “Cabaret” Star of Rocky Horror Show” and “Sweeney Todd” Star of “Chicago” and “Peter Pan” JAN FINDLAY MARC DALIO ANTHONY ARDOLINO Star of “You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown” Star of “West Side Story” and “Miss Saigon” Star of “Rent” and “Paws Patrol” and “Man of La Mancha” DARLENE YANNETTA JACK MASSON MICHELE GOLDEN Star of “Sound of Music and “Chicago” Star of “Phantom of the Opera” Star of “Extremities” and “Romeo & Juliet” and “West Side Story” ANGELA MASI EMILY BOYER Star of “I Love you, You’re Perfect, Now Change” JOSH BOYER JOSH BOYER JOSH BOYER Star of “Mama Mia” and “Peter Pan” Star of “Matilda” and “Spamalot” RICHARD BOYER DANIEL De RIANCHO Star of “Young Frankenstein” and “Chess” NICK TOMASELLI Star of “Peter Pan” and “Falsettoland” Star of “The Lion King”” and “”Zorro” GRADY MORGAN AVA HOSONITZ Star of “”The Lion King” and “Cinderella” ALISON BANCROFT Star of “Annie” and “Wizard of Oz” ALISON BANCROFT ANGELINA STIGLIANO Star of “Legally Blonde” and “Hairspray” Star of “”The Lion King” and “Ghost Princess” For the safety and comfort of our Audience and Performers A MASK OR FACE COVER IS MANDATORY and PLEASE HONOR SOCIAL DISTANCING You are Welcome to Bring a Blanket, a Lawn Chair, a Picnic Basket Bring Your own Refreshments if you like. -

Temecula Theater Your Experiences, Your Memories

TEMECULA THEATER YOUR EXPERIENCES, YOUR MEMORIES 2019 - 2020 SEASON #ExperienceTemeculaTheater Reasons we all #LOVETemecula! The City of Temecula celebrates 30 years of incorporation on Sunday, SUBSCRIBE & SAVE December 1, 2019. Temecula’s commitment to providing world-class, affordable, and accessible cultural experiences is evidenced by 2019-2020 Season Package Pricing offers music, dance, and Temecula Theater’s 15th Season offering music, dance, and theater theater lovers the opportunity to experience extraordinary lovers extraordinary experiences at memorable live performances, so evenings at your favorite series performances at a significant close to home. savings. Buy Series Packages and receive the deepest discount or Create Your Own Series by selecting five or more shows to Love builds communities and we are grateful for all the love and get the Pick 5 rates. As a Season Subscriber, you will be set for support from our talented artists, generous volunteers, dedicated the Season without worrying about sold-out performances or staff, and loyal patrons. Temecula’s Theater is dedicated to waiting in line to purchase tickets. encouraging, inspiring, and developing the next generation of performers, producers, presenters, and patrons. BENEFITS The Old Town Temecula Community Theater has entertained • Best Value over 700,000 visitors since opening in 2005. Temecula Presents • Preferred Seating continues the tradition by curating various genres for all ages on • Advance Purchase multiple stages, reflecting the diversity of our growing community by • Prior Notices showcasing legendary heroes and rising stars. • Free Ticket Delivery Temecula’s Theater Foundation, Resident Companies, and community performance partners show love by providing traditional and GROUP SALES contemporary experiences through musical theater, chorus, dance, speakers, and all our @ The Merc Series’. -

Origins of Rock the Seventies

from the definitive, illustrated encyclopedia of rock the definitive, illustrated encyclopedia of rock Richard Buskin, Alan Clayson, Joe Cushley, Rusty Cutchin, Jason Draper, Hugh Fielder, Mike Gent, Drew Heatley, Michael Heatley, Jake Kennedy, Colin Salter, Ian Shirley, John Tobler General Editor: Michael Heatley • Foreword by Scotty Moore FLAME TREE PUBLISHING from the definitive, illustrated encyclopedia of rock FlameTreeRock.com offers a very wide This is a FLAME TREE digital book range of other resources for your interest and entertainment: Publisher and Creative Director: Nick Wells Project Editor: Sara Robson Commissioning Editor: Polly Prior 1. Extensive lists and links of artists , Designer: Mike Spender and Jake The sunshine 1960s were followed by the comparatively grey 1970s. organised by decade: Sixties, Picture Research: Gemma Walters Yet a number of stars of that drab decade started their Contents Seventies etc. Production: Kelly Fenlon, Chris Herbert and Claire Walker life in the 1960s. 2. Free ebooks with the story of other Special thanks to: Joe Cushley, Jason Draper, Jake Jackson, Karen Fitzpatrick, Rosanna Singler and Catherine Taylor In Britain, the chameleon-like David Bowie suffered several musical genres, such as David Bowie ........................................4–5 years of obscurity, Status Quo were psychedelic popsters yet to soul, R&B, disco, rap & Hip Hop. Based on the original publication in 2006 discover 12-bar blues, while Humble Pie was formed by The Eagles ..........................................6–7 -

2020|2021 Season

OUR ALL NEW 2020|2021 SEASON SHARE THIS BROCHURE WITH YOUR FRIENDS Click to Open THE BAND’S VISIT SEPTEMBER 8 – 13, 2020 1776 OCTOBER 6 – 11, 2020 Dear Theatregoer, HADESTOWN We are so excited to start this new decade with a thrilling JANUARY 19 – 24, 2021 lineup for our 2020-2021 Season. We have everything from the top musicals currently playing on Broadway, fresh THE CHER SHOW national tours, a special pre-Broadway engagement and MARCH 16 – 21, 2021 returning San Diego audience favorites, and for the first time in 10 years, we are adding a play to our exciting lineup. TOOTSIE MAY 11 – 16, 2021 The road from Broadway to San Diego is shorter than ever, and that has everything to do with the support of our PRETTY WOMAN: sponsors, starting with title sponsor, San Diego County THE MUSICAL Credit Union® for their generous and ongoing support, and JUNE 1 – 6, 2021 you, our audience, for the trust we strive to maintain with TO KILL A each and every presentation. MOCKINGBIRD JUNE 22 – 27, 2021 Whether you are returning for another season, just joined us for the first time, or still considering a Season Ticket Package, we can’t wait to welcome you to the theatre for another incredible season. My Best, Vanessa Davis, General Manager Broadway San Diego — A Nederlander Presentation OUR ALL NEW 2020|2021 THE BAND’S VISIT SEPTEMBER 8 – 13, 2020 Patrick Page 1776 and Amber Gray in OCTOBER 6 – 11, 2020 HADESTOWN. Photo by Matthew HADESTOWN Murphy. JANUARY 19 – 24, 2021 THE CHER SHOW MARCH 16 – 21, 2021 TOOTSIE MAY 11 – 16, 2021 PRETTY WOMAN: THE MUSICAL JUNE 1 – 6, 2021 TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD JUNE 22 – 27, 2021 EXTRA SEASONDISNEY’S EVENTS THE LION KING AUGUST 12 – 30, 2020 IRVING BERLIN’S WHITE CHRISTMAS NOVEMBER 24 – 29, 2020 LES MISÉRABLES MARCH 2 – 7, 2021 “Bring Him Home” - Nick Cartell as ‘Jean Valjean’ in the new national tour of LES MISÉRABLES. -

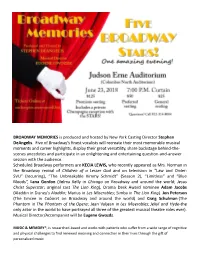

BROADWAY MEMORIES Is Produced and Hosted by New York Casting Director Stephen Deangelis

BROADWAY MEMORIES is produced and hosted by New York Casting Director Stephen DeAngelis. Five of Broadway’s finest vocalists will recreate their most memorable musical moments and career highlights, display their great versatility, share backstage behind-the- scenes anecdotes and participate in an enlightening and entertaining question-and-answer session with the audience. Scheduled Broadway performers are KECIA LEWIS, who recently appeared as Mrs. Norman in the Broadway revival of Children of a Lesser God and on television in “Law and Order: SVU” (recurring), “The Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt” (Season 2), “Limitless” and “Blue Bloods”, Lana Gordon (Velma Kelly in Chicago on Broadway and around the world; Jesus Christ Superstar; original cast The Lion King), Drama Desk Award nominee Adam Jacobs (Aladdin in Disney’s Aladdin; Marius in Les Miserables; Simba in The Lion King). Jon Peterson (The Emcee in Cabaret on Broadway and around the world) and Craig Schulman (The Phantom in The Phantom of the Opera; Jean Valjean in Les Miserables; Jekyl and Hyde-the only actor in the world to have portrayed all three of the greatest musical theatre roles ever). Musical Director/Accompanist will be Eugene Gwozdz. MUSIC & MEMORY®, is researched-based and works with patients who suffer from a wide range of cognitive and physical challenges to find renewed meaning and connection in their lives through the gift of personalized music. STEPHEN DeANGELIS (Producer/Host) has produced over 300 different Broadway concerts at venues in New York and across the United States featuring a multitude of Broadway stars including many Tony Award and Drama Desk Award winners and nominees, stars from hit television series and films whose roots are on stage and Broadway's fastest rising young performers. -

John, Sir Elton (B.1947) by Nathan G

John, Sir Elton (b.1947) by Nathan G. Tipton Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2002, glbtq, Inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com Sir Elton John on stage in 2008. Photograph by Elton John has, over five decades, achieved an amazingly successful track record in Richard Mushet. the music industry. He was not only the biggest-selling pop superstar of the 1970s, Image appears under the but, more surprisingly, he continues to retain popularity among his fans and respect Creative Commons from music critics. Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license. Elton John holds a music industry record for most consecutive singles placed in the Top 40, a string that began in 1970 and was broken only in 2000. Stephen Erlewine has noted that, although Elton John has endured temporary slumps in creativity and sales, he continues to craft contemporary pop standards that showcase his musical versatility. John's combination of melodic skills, dynamic charisma, and raucous performance style has made him a remarkably popular musical artist. Elton John was born Reginald Kenneth Dwight in Pinner, Middlesex, England on March 25, 1947. Dwight began playing piano at age four and, when he was eleven, won a scholarship to the Royal Academy of Music in London. After six years at school, he left in order to break into the music business. In 1961 he joined his first band, Bluesology, but left in 1966 because of creative differences with bandleader Long John Baldry. During this time Dwight had answered a Liberty Records advertisement for songwriters; and, though he failed the vocal audition, he was given a stack of lyrics written by Bernie Taupin, a young songwriter from Lincolnshire who had also answered the ad. -

Spamalot the Talent Behind the Show

Summer 2007 CAMP BROADWAY LLC CAMP BROADWAY ® NEW YORK SSttaaggeeNNOOTTEESS A FIELD GUIDE FOR TEACHERS Table of Contents Welcome from Dallas Summer Musicals . .3 Using the Field Guide . .4 A Brief History of the Broadway Musical . .5 Spamalot The Talent Behind the Show . .8 Spamalot: A Production History . .8 Spamalot: Synopsis . .9 Spamalot: Background Information . .10 Spamalot: Lesson Ideas . .12 The Broadway Guide to Theatergoing Etiquette . .14 The Dallas Summer Musicals School of Musical Theatre and Kids Club . .16 2 WelcomeDallas from Summer Musicals Summer 2007 Welcome to Dallas Summer Musicals! We’re so glad you could join us! Musical theater is a unique American creation. It’s also a joyful mixture of song and story, and, since 1945, Dallas Summer Musicals has brought the finest musicals to Dallas. Want to know what goes into making a musical? Just two simple ingredients: singing and acting (song and story). There’s just something about a song that makes a story mean more than just regular speech. It touches us in a different way. Whether a show uses classical music or rock, a musical uses music to tell its story, to suggest feelings, emotions, and attitudes. As long as it mixes song and story, musical theater can be about literally anything, and this season’s shows are great examples of the wide range of subjects. From the blockbuster musical Wicked to the sweeping epic of Camelot, each production reveals a different aspect of what makes musical theater so special. The story of Dallas Summer Musicals is a long and honored one, and by learning about and attending one of our shows, you are now part of that story too! Sincerely, Michael A.