The Discourse and Reality of Faith-Based Development in San Carlos, Philippines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

December 7, 2008

Pahayagan ng Partido Komunista ng Pilipinas ANG Pinapatnubayan ng Marxismo-Leninismo-Maoismo English Edition Vol. XXXIX No. 23 December 7, 2008 www.philippinerevolution.net Editorial Unite to fight and defeat cha-cha! he Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) ly rushing Congress to pass various resolutions to ef- strongly condemns Arroyo's stepped-up cha-cha fect cha-cha in whatever form and planning on using T(charter change) offensive and calls on the en- the Supreme Court in 2009 once it is dominated by Ar- tire Filipino people to resist and defeat her attempts royo appointees to give their offensive a semblance of to perpetuate her rule. legality. Arroyo is now attempting all kinds of manipula- With the people's wrath against Arroyo and their tions and schemes to be able to hold on to power. As refusal for her to rule much longer written all over, she the end of her term in 2010 nears, she has now be- is determined to employ her military, police and oth- come all the more desperate to extend her stay in er security forces to crush the mass demonstrations Malacañang to avoid the people's verdict for the innu- and other protests expected to erupt against her cha- merable heinous crimes she has committed against cha. Arroyo is deathly afraid that these protests will the country and people. snowball into a mass uprising against her rule. Should The Arroyo family and its cohorts are now brazen- this not be enough, she has in reserve another impo- ly revving up their cha-cha offensive by distorting sition of "emergency rule" or outright martial law. -

Facts & Figures

The Capiz Times THE VOICE OF THE CAPICEÑO ENTERED AS SECOND-CLASS MAIL AT THE ROXAS CITY POST OFFICE ON FEB. 25, 1982 VOL. XXXI NO. 43 August 12–18, 2013 P15 IN CAPIZ Social Action Center mission serves 472 patients Roxas City—Some 472 patients from the St. Damien of Molokai Mission Station benefited from the various medical services during the Medical-Dental-Circumcision Mission and Bloodletting Activity led by the Social Action Center, Aug. 17 in Brgy. Maindang, Cuartero, Capiz. Of the total patients, 162 adults and 97 children availed themselves of medical checkup; 120, dental services; and 93 boys, free circumcision. The Mission Station was Red Cross and the Local likewise supportive of the Government Unit of Cuartero Bloodletting Activity of the through its Municipal Health Capiz Red Cross through its Office, The St. Damien of volunteer blood donors. The Molokai Mission Station patients were served through covers six neighboring volunteer doctors, dentists barangays in Cuartero and nurses from the Philippine including Agdahon, Mainit, Army, the Capiz Red Cross, Maindang, Balingasag, the Cuartero’s health unit and Sinabsaban and Lunayan. other volunteers. Rev. Mark Granflor, Medicines dispensed to SAC director, said it was no the beneficiaries came from less than the bishop of the donations of doctors, the 61st Archdiocese of Capiz, Most Infantry Battalion, drugstores, Rev. Jose Advincula, Jr. drug companies and various D.D., accompanied by Rev. individual donors collected Fr. Digno V. Jore, Jr. who by the Social Action Center dropped by during the event. (SAC). Granflor said the bishop SAC worked in wanted to surprise the group partnership with the 61st with his visit but it turned out WITHIN THE WALLS Infantry Battalion, Philippine that he was the one who got Members of the Sarayawan Dance Company of the Colegio de la Purisima Concepcion wow audiences with their Army headed by LTC. -

Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 2014

This event is dedicated to the Filipino People on the occasion of the five- day pastoral and state visit of Pope Francis here in the Philippines on October 23 to 27, 2014 part of 22- day Asian and Oceanian tour from October 22 to November 13, 2014. Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 ―Mercy and Compassion‖ a Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 2014 Contents About the project ............................................................................................... 2 About the Theme of the Apostolic Visit: ‗Mercy and Compassion‘.................................. 4 History of Jesus is Lord Church Worldwide.............................................................................. 6 Executive Branch of the Philippines ....................................................................... 15 Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ....................................................................... 15 Vice Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines .............................................................. 16 Speaker of the House of Representatives of the Philippines ............................................ 16 Presidents of the Senate of the Philippines .......................................................................... 17 Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the Philippines ...................................................... 17 Leaders of the Roman Catholic Church ................................................................ 18 Pope (Roman Catholic Bishop of Rome and Worldwide Leader of Roman -

Race and Ethnicity in the Era of the Philippine-American War, 1898-1914

Allegiance and Identity: Race and Ethnicity in the Era of the Philippine-American War, 1898-1914 by M. Carmella Cadusale Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the History Program YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY August, 2016 Allegiance and Identity: Race and Ethnicity in the Era of the Philippine-American War, 1898-1914 M. Carmella Cadusale I hereby release this thesis to the public. I understand that this thesis will be made available from the OhioLINK ETD Center and the Maag Library Circulation Desk for public access. I also authorize the University or other individuals to make copies of this thesis as needed for scholarly research. Signature: M. Carmella Cadusale, Student Date Approvals: Dr. L. Diane Barnes, Thesis Advisor Date Dr. David Simonelli, Committee Member Date Dr. Helene Sinnreich, Committee Member Date Dr. Salvatore A. Sanders, Dean of Graduate Studies Date ABSTRACT Filipino culture was founded through the amalgamation of many ethnic and cultural influences, such as centuries of Spanish colonization and the immigration of surrounding Asiatic groups as well as the long nineteenth century’s Race of Nations. However, the events of 1898 to 1914 brought a sense of national unity throughout the seven thousand islands that made the Philippine archipelago. The Philippine-American War followed by United States occupation, with the massive domestic support on the ideals of Manifest Destiny, introduced the notion of distinct racial ethnicities and cemented the birth of one national Philippine identity. The exploration on the Philippine American War and United States occupation resulted in distinguishing the three different analyses of identity each influenced by events from 1898 to 1914: 1) The identity of Filipinos through the eyes of U.S., an orientalist study of the “us” versus “them” heavily influenced by U.S. -

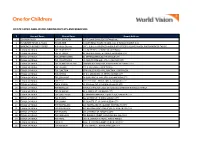

List of Ecpay Cash-In Or Loading Outlets and Branches

LIST OF ECPAY CASH-IN OR LOADING OUTLETS AND BRANCHES # Account Name Branch Name Branch Address 1 ECPAY-IBM PLAZA ECPAY- IBM PLAZA 11TH FLOOR IBM PLAZA EASTWOOD QC 2 TRAVELTIME TRAVEL & TOURS TRAVELTIME #812 EMERALD TOWER JP RIZAL COR. P.TUAZON PROJECT 4 QC 3 ABONIFACIO BUSINESS CENTER A Bonifacio Stopover LOT 1-BLK 61 A. BONIFACIO AVENUE AFP OFFICERS VILLAGE PHASE4, FORT BONIFACIO TAGUIG 4 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_HEAD OFFICE 170 SALCEDO ST. LEGASPI VILLAGE MAKATI 5 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_BF HOMES 43 PRESIDENTS AVE. BF HOMES, PARANAQUE CITY 6 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_BETTER LIVING 82 BETTERLIVING SUBD.PARANAQUE CITY 7 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_COUNTRYSIDE 19 COUNTRYSIDE AVE., STA. LUCIA PASIG CITY 8 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_GUADALUPE NUEVO TANHOCK BUILDING COR. EDSA GUADALUPE MAKATI CITY 9 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_HERRAN 111 P. GIL STREET, PACO MANILA 10 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_JUNCTION STAR VALLEY PLAZA MALL JUNCTION, CAINTA RIZAL 11 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_RETIRO 27 N.S. AMORANTO ST. RETIRO QUEZON CITY 12 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_SUMULONG 24 SUMULONG HI-WAY, STO. NINO MARIKINA CITY 13 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP 10TH 245- B 1TH AVE. BRGY.6 ZONE 6, CALOOCAN CITY 14 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP B. BARRIO 35 MALOLOS AVE, B. BARRIO CALOOCAN CITY 15 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP BUSTILLOS TIWALA SA PADALA L2522- 28 ROAD 216, EARNSHAW BUSTILLOS MANILA 16 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP CALOOCAN 43 A. MABINI ST. CALOOCAN CITY 17 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP CONCEPCION 19 BAYAN-BAYANAN AVE. CONCEPCION, MARIKINA CITY 18 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP JP RIZAL 529 OLYMPIA ST. JP RIZAL QUEZON CITY 19 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP LALOMA 67 CALAVITE ST. -

CBCP Monitor

CBCP JANUARY 25 - 27, 2021 - VOL 25, NO.Monitor 2 [email protected] PROTAGONIST OF TRUTH, PROMOTER OF PEACE Bishops offer church facilities Red-tagging incidents as vaccination hubs ‘worrisome’ — CBCP THE country’s Catholic bishops By Roy Lagarde on Jan. 28 said they are willing to transform church facilities into Covid-19 vaccination sites. THE spate of red- Archbishop Romulo Valles, tagging incidents in president of the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the Philippines, the country has been said the Church’s role is to serve described as ‘worrisome’ God and His people. by the Catholic Bishops’ And during this pandemic, he Conference of the said that helping in the vaccine Philippines. roll-out is an effective way they can do those things. Speaking in a virtual press “The bishops decided to offer, conference on Jan. 28, CBCP vice if needed, church facilities to be president Bishop Pablo Virgilio David vaccination centers or facilities of Kalookan said the recent red-tagging related to the vaccination involving activists and universities is a program,” Valles said in a virtual serious cause for concern. press conference after their two- “It is becoming worrisome. day online plenary assembly. Definitely,” David said. “I think The bishops acknowledged there is reason for people to be how daunting the vaccination afraid when that becomes a trend.” program can be so they wanted The prelate spoke to the media to help out. following their unprecedented online “We can offer our church plenary assembly, that saw over 80 facilities to help in this bishops discuss pressing issues and massive and complicated and the Church’s continuing response very challenging program of According to him, red-tagging vaccination,” Valles said. -

August 21, 2011

Pahayagan ng Partido Komunista ng Pilipinas ANG Pinapatnubayan ng Marxismo-Leninismo-Maoismo English Edition Vol XLII No. 16 August 21, 2011 www.philippinerevolution.net Editoryal Resist the US imperialist charter change scheme n collusion with the puppet officials of the away with national minimum wage standards. The Aquino government, US imperialism is now Herrerra Law also amended the Labor Code, Ivigorously pushing for the amendment of the paving the way for labor contractualization and 1987 Philippine constitution. In another case of additional restrictions on the right to strike. Cap- brazen US intervention in the country's internal italists made use of these laws to further depress affairs, the US is campaigning for the removal of wages and block workers from forming unions. For provisions in the constitution that prohibit for- the past 20 years, workers' wages have been vir- eign corporations from having majority control tually at a standstill, falling way behind the rap- over companies operating in the Philippines. id rise in the cost of living and condemning Fil- The Filipino people must strongly oppose ipino workers to ever worsening social condi- these US imperialist maneuvers as they further tions. Since then, the number of unions and trample on the Philippines' economic sovereignty unionized workers in the Philippines has dropped which has already taken a severe beating in the by almost 70%. last 25 years due to the policies of liberalization, Successive IMF-approved Medium Term Philip- deregulation, privatization and denationaliza- pine Development Plans (MTPDPs) were imple- tion. The amendments being pushed by the US mented by the Aquino, will complete the economic recolonization of the Ramos, Estrada and Arroyo Philippines and lead to ever deeper crisis. -

Demons, Saviours, and Narrativity in a Vernacular Literature1

ASIATIC, VOLUME 4, NUMBER 2, DECEMBER 2010 Demons, Saviours, and Narrativity in a Vernacular Literature1 Corazon D. Villareal2 University of the Philippines Diliman Abstract Narratives from and on Panay and Negros in the Western Visayas region of the Philippines are generally called the sugilanon. Its origins are usually traced to the Visayan epics; the sugilanon receded in the background with the dominance of religio-colonial literature in the Spanish period (1660‟s-1898) but re-emerged as didactic narratives with the publication of popular magazines in Visayan in the 1930‟s. Tracking its development could be a way of writing a literary history of the region. The last 25 years has been a particularly exciting time in its development. Young, schooled writers are now writing with the “instinctual” writers, in a variety of languages, Hiligaynon, Kiniray-a, Filipino and even English and experiments in craft are evident. The study focuses on sugilanon in this period, in particular the sub-genre utilising spirit- lore as part of its imaginative repertoire. It explores the creative transformations of spirit-lore both in theme and narrative method in the sugilanon. Moreover, it seeks to explain the persistence of demons, dungans and other spirits even among writers with supposedly post-modern sensibilities. This may be attributed to residuality or to metaphorical ways of seeing. But the paper argues that spirit-lore is very much tied up with notions of social agency and historical continuity. Such questions could illuminate some aspects of narrativity in the vernacular. Abstract in Malay Naratif dari dan tentang Panay dan Negro di rantau Selatan Visaya, Filipina secara amnya digelar sugilanon. -

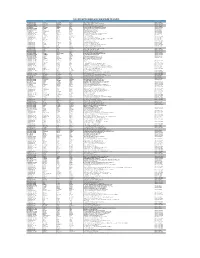

2019 Iiee Metro Manila Region Return to Sender

2019 IIEE METRO MANILA REGION RETURN TO SENDER STATUS firstName midName lastname EDITED ADDRESS chapterName RTS UNKNOWN ADDRESS ANSELMO FETALVERO ROSARIO Zone 2 Boulevard St. Brgy. May-Iba Teresa Metro East Chapter RTS UNKNOWN ADDRESS JULIUS CESAR AGUINALDO ABANCIO 133 MC GUINTO ST. MALASAGA, PINAGBUHATAN PASIG . Metro Central Chapter RTS UNKNOWN ADDRESS ALVIN JOHN CLEMENTE ABANO NARRA STA. ELENA IRIGA Metro Central Chapter RTS INSUFFICIENT ADDRESS Gerald Albelda Abantao NO.19 . BRGY. KRUS NA LIGAS. DILIMAN QUEZON CITY Metro East Chapter RTS NO RECEIVER JEAN MIGHTY DECIERDO ABAO HOLCIM PHILIPPINES INC. MATICTIC NORZAGARAY BULACAN Metro Central Chapter RTS INSUFFICIENT ADDRESS MICHAEL HUGO ABARCA avida towers centera edsa cor. reliance st. mandaluyong city Metro West Chapter RTS UNLOCATED ADDRESS Jeffrey Cabagoa ABAWAG 59 Gumamela Sta. Cruz Antipolo Rizal Metro East Chapter RTS NO RECEIVER Angelbert Marvin Dolinso ABELLA Road 12 Nagtinig San Juan Taytay Rizal Metro East Chapter RTS INSUFFICIENT ADDRESS AHERN SATENTES ABELLA NAGA-NAGA BRGY. 71 TACLOBAN Metro South Chapter RTS UNKNOWN ADDRESS JOSUE DANTE ABELLA JR. 12 CHIVES DRIVE ROBINSONS HOMES EAST SAN JOSE ANTIPOLO CITY Metro East Chapter RTS INSUFFICIENT ADDRESS ANDREW JULARBAL ABENOJA 601 ACACIA ESTATE TAGUIG CITY METRO MANILA Metro West Chapter RTS UNKNOWN ADDRESS LEONARDO MARQUEZ ABESAMIS, JR. POBLACION PENARANDA Metro Central Chapter RTS UNKNOWN ADDRESS ELONA VALDEZ ABETCHUELA 558 M. de Jesus St. San Roque Pasay City Metro South Chapter RTS UNLOCATED ADDRESS Franklin Mapa Abila LOT 3B ATIS ST ADMIRAL VILLAGE TALON TRES LAS PINAS CITY METRO MANILA Metro South Chapter RTS MOVED OUT Marie Sharon Segovia Abilay blk 10 lot 37 Alicante St. -

Negros Panaad Festival Dances: a Reflection of Negrenses' Cultural

Asia Pacific Journal of Multidisciplinary Research, Volume 8, No. 3, August 2020 _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Asia Pacific Journal of Negros Panaad Festival Dances: A Reflection Multidisciplinary Research of Negrenses’ Cultural Identity Vol. 8 No.3, 13-24 August 2020 Part III Randyll V. Villones P-ISSN 2350-7756 Philippine Normal University Visayas, Negros Occidental, Philippines E-ISSN 2350-8442 [email protected] www.apjmr.com ASEAN Citation Index Date Received: May 31, 2020; Date Revised: August 11, 2020 Abstract - Negrense cultural identity has been slowly eroded with the dynamics of virtual colonial cultural influences through social media. This sad state prompted the creation and organization of some cultural festival that will reawaken the cultural awareness and consciousness of every Negrense. This study aimed to analyze Negros Panaad festival dances to unearth the embedded cultural contexts which encapsulate the Negrenses’ Cultural Identity. The descriptive-narrative approach was employed to gather different dance characteristics, including historical background/context, movement description, costumes, accessories, props/dance implements, and music/rhythm. To examine the participants' understanding of the dance, its relation to everyday life activities, and worldview, the focused group discussion, and direct observation were conducted. Ten choreographers, ten dancers, five barangay officials, and five old-aged key informants, with a total of 30, served as participants of the study coming from different local government units joining the Panaad festival dances. Significant findings revealed that these dance characteristics manifested from festival dances were solid shreds of evidence of the different cultural contexts which rightfully mirrors the rootedness and the cultural undertone of Negrenses as a person in general. -

The Holy See

The Holy See POPE FRANCISANGELUSSaint Peter's Square Sunday, 25 October 2020[Multimedia] Dear Brothers and Sisters, Good morning! In today’s Gospel passage (cf. Mt 22:34-40), a doctor of the Law asks Jesus “which is the great commandment” (v. 36), that is, the principal commandment of all divine Law. Jesus simply answers: “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind” (v. 37). And he immediately adds: “And a second is like it, You shall love your neighbour as yourself” (v. 39). Jesus’ response once again takes up and joins two fundamental precepts, which God gave his people through Moses (cf. Dt 6:5; Lv 19:18). And thus he overcomes the snare that is laid for him in order “to test him” (Mt 22:35). His questioner, in fact, tries to draw him into the dispute among the experts of the Law regarding the hierarchy of the prescriptions. But Jesus establishes two essential principles for believers of all times; two essential principles of our life. The first is that moral and religious life cannot be reduced to an anxious and forced obedience. There are people who seek to fulfil the commandments in an anxious or forced manner, and Jesus helps us understand that moral and religious life cannot be reduced to anxious or forced obedience, but must have love as its precept. The second principle is that love must tend together and inseparably toward God and toward neighbour. This is one of the primary innovations of Jesus’ teachings, and it helps us understand that what is not expressed in love of neighbour is not true love of God; and, likewise, what is not drawn from one’s relationship with God is not true love of neighbour. -

Abp. Soc Calls Priests to Be 'Real Witnesses Amid Threats

CBCP APRIL 15 - 28, 2019, VOL 23, NO.Monitor 08 [email protected] PROTAGONIST OF TRUTH, PROMOTER OF PEACE Abp. Soc calls priests to be ‘real witnesses amid threats By Roy Lagarde PRIESTS are called to face “these dreary times of darkness” by being “real witnesses” amid “an angry disbelieving society,” a church official said on Holy Thursday. Those priests, said Archbishop Socrates Villegas of Lingayen- Dagupan, should also not be afraid to die or be killed for the Lord. “Brother priests, make friends with death. Let death not threaten you,” Villegas said in his Chrism Mass homily at the St. John the Evangelist Cathedral in Dagupan City. “The call to the priesthood is a call to die. It is clear. There is no priesthood without victimhood,” he said. To drive his point, the archbishop said that there’s nothing surprising with priests being threatened with death. In the first place, he said that priests should not have accepted ordination if they were afraid to die or be killed. “Death is not a threat. It is our destiny,” said Villegas, who is also a former president of the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the Philippines. Archbishop Socrates Villegas embraces a priest as he celebrates the Chrism Mass at the St. John the Evangelist Cathedral in Dagupan City April 18. COURTESY OF SABINS STUDIO Witnesses / A6 Pampanga’s old churches PH bishops condemn Sri Lanka attacks closed after earthquake CATHOLIC leaders in the Philippines joined the international community in condemning a series of blasts in Sri Lanka on Easter Sunday. Cardinal Luis Antonio Tagle on April 22 offered Mass at the Manila Cathedral on Monday for the victims of the bombings that killed almost 300 people.