Understanding Seon in Go Eun's 108 Poems in What (Mwonya 뭐냐)?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analytical Study of the Way of the Practice of Truc Lam Zen School in Vietnam

AN ANALYTICAL STUDY OF THE WAY OF THE PRACTICE OF TRUC LAM ZEN SCHOOL IN VIETNAM Bhikkhuni Bui Thi Thu Thuy (TN. Huệ Từ) A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Buddhist Studies) Graduate School Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University C.E. 2017 ii An Analytical Study of The Way of The Practice of Truc Lam Zen School in Vietnam Bhikkhuni Bui Thi Thu Thuy (TN. Huệ Từ) A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Buddhist Studies) Graduate School Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University C.E. 2017 (Copyright of Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University) iii iv Thesis Title : An Analytical Study of the Way of The Practice of Truc Lam Zen School in Vietnam Researcher : Bhikkhuni Bui Thi Thu Thuy Degree : Master of Arts (Buddhist Studies) Thesis Supervisory Committee : Phramaha Somphong Khunakaro, Dr., Pāli IX, B.A. (Educational Administration), M.A. (Philosophy), Ph.D. (Philosophy) : Asst. Prof. Dr. Sanu Mahatthanadull, B.A. (Advertising), M.A. (Buddhist Studies), Ph.D. (Buddhist Studies) Date of Graduation: March 10, 2018 Abstract This thesis is qualitative research with three objectives: l) to study the origin and development of the Way of the Practice of TLZS, 2) to analyze the content of the way of practice of TLZS and 3) to study the influences of the way of the practice of TLZS in Vietnam. The research methodology used is primarily documentary; data were collected from Vietnamese Zen texts; Taisho Tipiṭaka sources. The need for the current study is significant and provides a comprehensive, emphasize the meaning and value of the way of practice TLZS in the history of Vietnam. -

Thich Nhat Hanh the Keys to the Kingdom of God Jewish Roots

Summer 2006 A Journal of the Art of Mindful Living Issue 42 $7/£5 Thich Nhat Hanh The Keys to the Kingdom of God Jewish Roots The Better Way to Live Alone in the Jungle A Mindfulness Retreat for Scientists in the Field of Consciousness A Convergence of Science and Meditation August 19–26, 2006 Science studies the brain from your family to a seven-day mindfulness In the beautiful setting of Plum outside, but do we know what happens retreat to learn about our minds using Village, we will enjoy the powerful when we look inside to experience Buddhist teachings and recent scientific energy of one hundred lay and mo- our own minds? Ancient Buddhist findings. nastic Dharma teachers, and enjoy the wisdom has been found to correspond brotherhood and sisterhood of living in During the retreat participants very closely with recent scientific dis- community. Lectures will be in English are invited to enjoy talks by and pose coveries on the nature of reality. Dis- and will be simultaneously translated questions to Zen Master Thich Nhat coveries in science can help Buddhist into French and Vietnamese. Hanh. Although priority will be given meditators, and Buddhist teachings on to neuroscientists and those who work consciousness can help science. Zen in the scientific fields of the brain, the Master Thich Nhat Hanh and the monks mind, and consciousness, everyone is and nuns of Plum Village invite you and welcome to attend. For further information and to register for these retreats: Upper Hamlet Office, Plum Village, Le Pey, 24240 Thenac, France Tel: (+33) 553 584858, Fax: (+33) 553 584917 E-mail: [email protected] www.plumvillage.org Dear Readers, Hué, Vietnam, March 2005: I am sitting in the rooftop restaurant of our lovely hotel overlooking the Perfume River, enjoying the decadent breakfast buffet. -

Buddhist Bibio

Recommended Books Revised March 30, 2013 The books listed below represent a small selection of some of the key texts in each category. The name(s) provided below each title designate either the primary author, editor, or translator. Introductions Buddhism: A Very Short Introduction Damien Keown Taking the Path of Zen !!!!!!!! Robert Aitken Everyday Zen !!!!!!!!! Charlotte Joko Beck Start Where You Are !!!!!!!! Pema Chodron The Eight Gates of Zen !!!!!!!! John Daido Loori Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind !!!!!!! Shunryu Suzuki Buddhism Without Beliefs: A Contemporary Guide to Awakening ! Stephen Batchelor The Heart of the Buddha's Teaching: Transforming Suffering into Peace, Joy, and Liberation!!!!!!!!! Thich Nhat Hanh Buddhism For Beginners !!!!!!! Thubten Chodron The Buddha and His Teachings !!!!!! Sherab Chödzin Kohn and Samuel Bercholz The Spirit of the Buddha !!!!!!! Martine Batchelor 1 Meditation and Zen Practice Mindfulness in Plain English ! ! ! ! Bhante Henepola Gunaratana The Four Foundations of Mindfulness in Plain English !!! Bhante Henepola Gunaratana Change Your Mind: A Practical Guide to Buddhist Meditation ! Paramananda Making Space: Creating a Home Meditation Practice !!!! Thich Nhat Hanh The Heart of Buddhist Meditation !!!!!! Thera Nyanaponika Meditation for Beginners !!!!!!! Jack Kornfield Being Nobody, Going Nowhere: Meditations on the Buddhist Path !! Ayya Khema The Miracle of Mindfulness: An Introduction to the Practice of Meditation Thich Nhat Hanh Zen Meditation in Plain English !!!!!!! John Daishin Buksbazen and Peter -

Contents Transcriptions Romanization Zen 1 Chinese Chán Sanskrit Name 1.1 Periodisation Sanskrit Dhyāna 1.2 Origins and Taoist Influences (C

7/11/2014 Zen - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Zen From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Zen is a school of Mahayana Buddhism[note 1] that Zen developed in China during the 6th century as Chán. From China, Zen spread south to Vietnam, northeast to Korea and Chinese name east to Japan.[2] Simplified Chinese 禅 Traditional Chinese 禪 The word Zen is derived from the Japanese pronunciation of the Middle Chinese word 禪 (dʑjen) (pinyin: Chán), which in Transcriptions turn is derived from the Sanskrit word dhyāna,[3] which can Mandarin be approximately translated as "absorption" or "meditative Hanyu Pinyin Chán state".[4] Cantonese Zen emphasizes insight into Buddha-nature and the personal Jyutping Sim4 expression of this insight in daily life, especially for the benefit Middle Chinese [5][6] of others. As such, it de-emphasizes mere knowledge of Middle Chinese dʑjen sutras and doctrine[7][8] and favors direct understanding Vietnamese name through zazen and interaction with an accomplished Vietnamese Thiền teacher.[9] Korean name The teachings of Zen include various sources of Mahāyāna Hangul 선 thought, especially Yogācāra, the Tathāgatagarbha Sutras and Huayan, with their emphasis on Buddha-nature, totality, Hanja 禪 and the Bodhisattva-ideal.[10][11] The Prajñāpāramitā Transcriptions literature[12] and, to a lesser extent, Madhyamaka have also Revised Romanization Seon been influential. Japanese name Kanji 禅 Contents Transcriptions Romanization Zen 1 Chinese Chán Sanskrit name 1.1 Periodisation Sanskrit dhyāna 1.2 Origins and Taoist influences (c. 200- 500) 1.3 Legendary or Proto-Chán - Six Patriarchs (c. 500-600) 1.4 Early Chán - Tang Dynasty (c. -

Groundwork Buddhist Studies Reader

...thus we have heard... (may be reproduced free forever) Buddhist Studies Reader Published by: Groundwork Education www.layinggroundwork.org Compiled & Edited by Jeff Wagner Second Edition, May 2018 This work is comprised of articles and excerpts from numerous sources. Groundwork and the editors do not own the material, claim copyright or rights to this material, unless written by one of the editors. This work is distributed as a compilation of educational materials for the sole use as non-commercial educational material for educators. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. You are free to edit and share this work in non-commercial ways. Any published derivative works must credit the original creator and maintain this same Creative Commons license. Please notify us of any derivative works or edits. "53 Wearing the broad-brimmed hat of the west, symbolic of the forces that guard the Buddhist Studies Reader wilderness, which is the Natural State of the Dharma and the true path of man on Earth: Published by Groundwork Education, compiled & edited by Jeff Wagner all true paths lead through mountains-- The Practice of Mindfulness by Thích Nhất Hạnh ..................................................1 With a halo of smoke and flame behind, the forest fires of the kali-yuga, fires caused by Like a Leaf, We Have Many Stems by Thích Nhất Hạnh ........................................4 the stupidity of those who think things can be gained and lost whereas in truth all is Mindfulness -

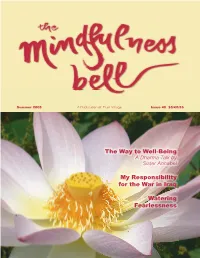

The Way to Well-Being My Responsibility for the War in Iraq

Summer 2008 A Publication of Plum Village Issue 48 $8/%8/£6 The Way to Well-Being A Dharma Talk by Sister Annabel My Responsibility for the War in Iraq Watering Fearlessness ISSUE NO. 48 - SUMMER 2008 Dharma Talk 4 Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh Talks about Tibet 6 The Way to Well-Being By Sister Annabel, True Virtue War’s Aftermath 12 A War Is Never Over Healing and Transformation By Trish Thompson 29 The First Precept 14 Question By Julie Hungiville LeMay By Paul Davis 30 The Leaves of One Tree 15 Spanning a Bridge By Le Thu Thuy By Sister Dang Nghiem 32 On Love and Being Gay 18 “First Time in Vietnam?” By Laurie Arron By Brian McNaught 34 Blue Sky Practice By Susan Hadler Heart to Heart 35 The Fifth Mindfulness Training By Evelyn van de Veen, Scott Morris, and Paul Baranowski Children’s Wisdom 37 Paint a Portrait of Me By Brooke Mitchell 38 The Helping Hand By Brother Phap Dung 40 Bell of Mindfulness By Terry Cortes-Vega 20 My Responsibility for the War in Iraq Sangha News By Bruce Campbell 41 Thay Rewrites the Five Contemplations; New Dharma Teachers Ordained at Plum Village; 20 The Light at the Q&A about Blue Cliff Tip of the Candle By Claude Anshin Thomas Book Reviews Gift of Non-Fear 44 World As Lover, World As Self By Joanna Macy 23 Getting Better, not Bitter The Dharma in Tanzania 44 Buddha Mind, Buddha Body By Thich Nhat Hanh By Karen Brody 25 Watering Fearlessness By David C. -

Reading Maxine Hong Kingston's the Fifth Book of Peace

UC Santa Barbara Journal of Transnational American Studies Title Life, Writing, and Peace: Reading Maxine Hong Kingston's The Fifth Book of Peace Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/68t2k01g Journal Journal of Transnational American Studies, 1(1) Author Shan, Te-Hsing Publication Date 2009-02-16 DOI 10.5070/T811006948 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Life, Writing, and Peace: Reading Maxine Hong Kingston’s The Fifth Book of Peace TE‐HSING SHAN I. A Weird and Intriguing Text “If a woman is going to write a Book of Peace, it is given her to know devastation”— thus begins Maxine Hong Kingston’s The Fifth Book of Peace (2003).1 Unlike her former award‐winning and critically acclaimed works—The Woman Warrior (1976), China Men (1980), and Tripmaster Monkey: His Fake Book (1989)—the reception of her latest book has been cool, to say the least. As of November 2008, there were only three entries on The Fifth Book of Peace in the MLA International Bibliography, in sharp contrast to the numbers on The Woman Warrior (273 entries), China Men (90 entries), and Tripmaster Monkey (63 entries). These three entries include an eight‐page book essay published in China, a twelve‐page journal article on Kingston’s three works published in Turkey, and a U.S. dissertation on three Asian American female writers. In addition, there are very few reviews in newspapers and journals. This is indeed a phenomenon unthinkable for a writer who has been hailed as one of the most frequently taught writers living in the U.S. -

A Psychological Analysis of Physical and Mental Pain in Buddhism Ashin

A Psychological Analysis of Physical and Mental Pain in Buddhism Ashin Sumanacara1 Mahidol University, Thailand. Pain is a natural part of life and all of us. Ordinary people are inflicted with physical or mental pain. In this paper, firstly we will analyse the concept of physical and mental pain according to the Pali Nikāyas. Next we will discuss the causes of physical and mental pain, and investigate the unwholesome roots: greed (lobha), hatred (dosa) and delusion (moha), and their negative roles in causing physical and mental pain. Then we will highlight the Buddhist path to overcoming physical and mental pain. Finally we will discuss mindfulness and the therapeutic relationship. Mindfulness, as it is understood and applied in Buddhism, is a richer theory than thus far understood and applied in Western psychotherapy. Within Buddhism the development of mindfulness must be understood to be interrelated with the maturity of morality (sīla), concentration (samādhi) and wisdom (paññā). A Word about Buddhism Buddhism, a spiritual movement, arose from the prevalent intellectual, political and cultural milieu of Indian society in the 6th century BCE and has been an influential cultural force in Asia for more than 2550 years. In recent decades, it has gained acceptance in the West, largely due to its solution of mental pain of human beings through mindfulness meditation. The core teachings of the Buddha are contained in the Four Noble Truths, which are as follows: (1) Dukkha: life is characterized by pain; (2) Samudaya: the cause of pain which is craving (taṇhā); (3) Nirodha: pain can be ended by the cessation of craving; and (4) Magga: there is a way to achieve the cessation of pain, which is the Noble Eightfold Path (ariya-aṭṭhangika-magga). -

Thich Nhat Hanh

INNER+OUTER WORLDS practice PATH OF PEACE Why I’m a Student of Thich Nhat Hanh I know of no spiritual teacher or person who more fully embodies peace and compassionate understanding than Thich Nhat Hanh, or Thay, as he is lovingly known by his students. “ALL RELIGIONS and spiritual traditions,” William they are right they are willing to kill or be killed for their James famously wrote, “begin with the cry ‘Help!’” Like ideals, Thay realizes that the only true path to peace is to find and grow peace within each of us, to cultivate compas- so many, I began my spiritual quest in earnest when I sion and understanding, and to understand how we all are began to heal consciously from an instance of violence interconnected. in my early childhood and the pain and confusion Many of Thay’s most moving teachings come in the form around it. Why, I wanted—I needed—to know, did bad of poems. In his poem “Call Me by My True Name,” written things happen, not only on the personal level, but all in 1978, he remembers with sorrow the many Vietnamese around us in the world? The world is full of injustice who died trying to escape their country on boats—in a situa- tion not dissimilar from that of many Syrian refugees today. and destruction: how are we to understand our present In this poem, Thay explores entering into the experiences moment and transform it? I needed a larger frame. of many different beings: I am, he writes, “a bud on a spring I had read the Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh’s work branch,” a “frog swimming happily,” a “child in Uganda all before, and I knew to go back to his writing and teachings. -

An Embracing Thought: Contemporary Sōtō Interpretations of Hishiryō

This is the Accepted Manuscript for a research published by Taylor & Francis in Contemporary Buddhism: An Interdisciplinary journal vol.17, no. 1, on April 5th 2016. The final edition is available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14639947.2016.1164948 . See also: http://www.tandfonline.com/toc/rcbh20/current#.Vv6u_npO8pc An Embracing Thought: Contemporary Sōtō Interpretations of Hishiryō Eitan Bolokan School of Philosophy, Tel-Aviv University. The term hishiryō (非思 nonthinking), is found in many of Dgen Zenji's 道 元禅師 (1200-53) writings and sermons, mostly in the context of the practice of sitting known as zazen (坐禅 sitting Zen) or more specifically as shikantaza (只管打坐 just sitting).i In recent decades, thanks to the growing number of available English translations of Dgen's works, the term has been translated in various ways. Wadell and Abe (1973, 123), Kim (2007, 80), and Bielefeldt (1988, 189) used the translation 'nonthinking'. Kasulis (1989, 72), on the other hand, rendered it 'without thinking', while Leighton and Okumura (2004, 327) and Tanahashi and Levitt (2011, 301) opted for 'beyond thinking'. In this article I use either 'nonthinking' or simply the original, hishiryō. The term hishiryō is not one of Dgen's own expressions but can be found in various texts throughout Zen history which predate Dgen: Lotus Sutra (法華経 Ch. Fahua jing), Sutra of Manjusri Speaking of the Inconceivable State of Buddhahood (文殊師利所不思議境界経 Ch. Wenshu Shi li Suo Shuo Bu Siyi Fo Jingjie Jing), the treatise Faith in Mind (信心銘 Ch. Xinxin ming), and the Buddha-Realm-Sutra ( 境界経 Ch. Fo Jingjie Jing) (Harada 1985, 26). -

European Buddhist Traditions Laurence Cox, National University

European Buddhist Traditions Laurence Cox, National University of Ireland Maynooth Abstract: This chapter covers those Buddhist traditions which are largely based in Europe, noting some of the specificities of this history as against the North American with which it is sometimes conflated. While the reception history of Buddhism in Europe stretches back to Alexander, Buddhist organization in Europe begins in the later nineteenth century, with the partial exception of indigenous Buddhisms in the Russian Empire. The chapter discusses Asian- oriented Buddhisms with a strong European base; European neo-traditionalisms founded by charismatic individuals; explicitly new beginnings; and the broader world of “fuzzy religion” with Buddhist components, including New Age, “night-stand Buddhists”, Christian creolizations, secular mindfulness and engaged Buddhism. In general terms European Buddhist traditions reproduce the wider decline of religious institutionalization and boundary formation that shapes much of European religion generally. Keywords: Buddhism, Buddhist modernism, creolization, Europe, immigration, meditation, night-stand Buddhists, Western Buddhism In 1908, the London investigative weekly Truth hosted a debate between two Burmese- ordained European bhikkhus (monks), U Dhammaloka (Laurence Carroll?) and Ananda Metteyya (Allan Bennett). Objecting to newspaper reports presenting the latter, recently arrived in Britain, as the first bhikkhu in Europe, Dhammaloka argued on July 8th that Ananda Metteyya had not been properly ordained, citing the Upasampada-Kammavacana to show that ordinands must state their freedom from various diseases, including asthma (which Bennett suffered from). Ananda Metteyya replied on July 15th with a discussion of the Burmese Kammavacana and the Mahavagga and stated that he had believed himself cured at the time of ordination. -

Engaged Buddhism

Buddhism Buddhism and Social Action: Engaged Buddhism Buddhism and Social Action: Engaged Buddhism Summary: Pioneered by the Vietnamese monk Thich Nhat Hanh in the 1970s, “Engaged Buddhism” brings a Buddhist perspective to the ongoing struggle for social and environmental justice in America. Some observers may associate Buddhism, and especially Buddhist meditation, with turning inward away from the world. However, many argue that the Buddhist tradition, with its emphasis on seeing clearly into the nature of suffering and, thus, cultivating compassion, has a strong impetus for active involvement in the world’s struggles. This activist stream of Buddhism came to be called “Engaged Buddhism”— Buddhism energetically engaged with social concerns. Among the first to speak of Engaged Buddhism in the United States was the Vietnamese monk Thich Nhat Hanh. Hanh came to the United States during the Vietnam War to explain the meaning of Buddhist-led protests and demonstrations against the American-supported Saigon government and to offer a peace proposal. In 1978, the Buddhist Peace Fellowship, inspired by the work of Thich Nhat Hanh, was formed to extend the network of Buddhist peace workers to include people from all Buddhist streams. Today, the network is both national and international and aims to address issues of peace, the environment, and social justice from the standpoint of Buddhist practice as a way of peace. In the United States, the Buddhist Peace Fellowship has involved Buddhists in anti-nuclear campaigns, prison reform, and saving ancient forests. The American development of Engaged Buddhism has a multitude of examples and expressions. Many Buddhist-inspired and led programs are at the forefront of hospice care for the dying.