Migrant Mother, Exists in More Formats, Prints, and Places Than (Arguably) Any Other Photograph in the World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Student Companion To

A Student Companion To With the generous support of Jane Pauley and Garry Trudeau The Raymond Foundation Contents section 1: The Book and Its Context page 2 Who Was John Steinbeck? | Ellen MacKay page 3What Was the Dust Bowl? | Ellen MacKay page 6 Primary Sources Steinbeck Investigates the Migrant Laborer Camps Ellen MacKay: Dorothea Lange’s “Migrant Mother” and the Look of the Dust Bowl The Novel’s Reception The Wider Impact of The Grapes of Wrath page 10 What Makes The Grapes of Wrath Endure? Jonathan Elmer: Steinbeck’s Mythic Novel George Hutchinson: Hearing The Grapes of Wrath Christoph Irmscher: Teaching The Grapes of Wrath section 2: Sustainability, Bloomington, and the World of The Grapes of Wrath page 14 What Does Literature Have to Do with Sustainability? | Ellen MacKay page 15 Nature Writing Now: An Interview with Scott Russell Sanders An Excerpt from A Conservationist Manifesto | Scott Russell Sanders page 18 What Can Be Done?: Sustainablilty Then and Now Michael Hamburger Sara Pryor Matthew Auer Tom Evans page 22 Primary Access: The 1930s in Our Midst Ellen MacKay: Thomas Hart Benton, the Indiana Murals, and The Grapes of Wrath Nan Brewer: The Farm Security Administration Photographs: A Treasure of the IU Art Museum Christoph Irmscher: “The Toto Picture”: Writers on Sustainability at the Lilly Library section 3: The Theatrical Event of The Grapes of Wrath page 26 How Did The Grapes of Wrath Become a Play? | Ellen MacKay page 27 The Sound of The Grapes of Wrath: Ed Comentale: Woody Guthrie, Dust Bowl Ballads, and the Art and Science of Migratin’ Guthrie Tells Steinbeck’s Story: The Ballad of “The Joads” page 31 Another Look at the Joads’ Odyssey: Guthrie’s Illustrations. -

Picturing America at the KIA………………………………………………………………………………………3

at the Kalamazoo Institute of Arts 314 S. Park Street Kalamazoo, MI 49007 269/349-7775, www.kiarts.org 2 Table of Contents Information about Picturing America at the KIA………………………………………………………………………………………3 The Art John Singleton Copley, Mars, Venus and Vulcan: The Forge of Vulcan , 1754……………………….…………..………………4 Charles Willson Peale, The Reverend Joseph Pilmore , 1787……………………………………………………………………...5 John James Audubon, White Headed Eagle , 1828………………………………………………………………………..………...6 Hiram Powers, George Washington , 1838-1844……………………………………………………………………………………..7 Severin Roesen, Still Life with Fruit and Bird’s Nest , n.d………………………………………..…………………………………..8 Johann Mongels Culverhouse, Union Army Encampment , 1860…………………………………………………………………..9 William Gay Yorke, The Great Republic , 1861…………………………………………………………………..………………….10 Eastman Johnson, The Boy Lincoln , 1867………………………………………………………………………………….……….11 Robert Scott Duncanson, Heart of the Andes , 1871……………………………………………………………..………………...12 Albert Bierstadt, Mount Brewer from Kings River Canyon , 1872……………………………………………………..……..........13 Edmonia Lewis, Marriage of Hiawatha , 1872………………………………………………………………………….…………….14 Jasper Francis Cropsey, Autumn Sunset at Greenwood Lake, NY , 1876…………………………………………….…………15 Henry Ossawa Tanner, The Visitation , 1890-1900……………………………………………………..…………………………..16 Frederick William MacMonnies, Nathan Hale , 1890………………………………………………………………………………..17 William Merritt Chase, A Study in Pink (Mrs. Robert MacDougal), 1895………………………………………………..……….18 Alfred Stieglitz, The Steerage , 1907…………………………………………………………………………………………...........19 -

Iconic Images: the Stories They Tell

Curriculum Units by Fellows of the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute 2011 Volume I: Writing with Words and Images Iconic Images: The Stories They Tell Curriculum Unit 11.01.06 by Kristin M. Wetmore Introduction An important dilemma for me as an art history teacher is how to make the evidence that survives from the past an interesting subject of discussion and learning for my classroom. For the art historian, the evidence is the artwork and the documents that support it. My solution is to have students compare different approaches to a specific historical period because they will have the chance to read primary sources about each of the three images selected, discuss them, and then determine whether and how they reveal, criticize or correctly report the events that they depict. Students should be able to identify if the artist accurately represents an historical event and, if it is not accurately represented, what message the artist is trying to convey. Artists and historians interpret historical events. I would like my students to understand that this interpretation is a construction. Primary documents provide us with just one window to view history. Artwork is another window, but the students must be able to judge on their own the factual content of the work and the artist's intent. It is imperative that students understand this. Barber says in History beyond the Text that there is danger in confusing history as an actual narrative and "construction of the historians (or artist's) craft." 1 The Merriam Webster Dictionary defines iconic as "an emblem or a symbol." 2 The three images I have chosen to study are considered iconic images from the different time periods they represent. -

Harvest Histories: a Social History of Mexican Farm Workers in Canada Since 1974”

“Harvest Histories: A Social History of Mexican Farm Workers in Canada since 1974” by Naomi Alisa Calnitsky B.A. (Hons.), M.A. A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario ©2017 Naomi Calnitsky Abstract While concerns and debates about an increased presence of non-citizen guest workers in agriculture in Canada have only more recently begun to enter the public arena, this dissertation probes how migrant agricultural workers have occupied a longer and more complex place in Canadian history than most Canadians may approximate. It explores the historical precedents of seasonal farm labour in Canada through the lens of the interior or the personal on the one hand, through an oral history approach, and the external or the structural on the other, in dialogue with existing scholarship and through a critical assessment of the archive. Specifically, it considers the evolution of seasonal farm work in Manitoba and British Columbia, and traces the eventual rise of an “offshore” labour scheme as a dominant model for agriculture at a national scale. Taking 1974 as a point of departure for the study of circular farm labour migration between Mexico and Canada, the study revisits questions surrounding Canadian views of what constitutes the ideal or injurious migrant worker, to ask critical questions about how managed farm labour migration schemes evolved in Canadian history. In addition, the dissertation explores how Mexican farm workers’ migration to Canada since 1974 formed a part of a wider and extended world of Mexican migration, and seeks to record and celebrate Mexican contributions to modern Canadian agriculture in historical contexts involving diverse actors. -

Dorothea Lange, Her Migrant Mother, and the Nisei Internees | Quazen

Photographic Equality: Dorothea Lange, Her Migrant Mother, and The Nisei Internees | Quazen Quazen Home About Contact Advertise with us Photographic Equality: Dorothea Lange, Her Migrant Mother, and The Nisei Internees Submit an Article Published on October 8, 2009 by David J. Marcou in Biography Dorothea Lange’s images of poverty in Depression era America and of war-time Japanese-American internees are among the most iconic photographs of the twentieth century. David J. Marcou investigates the life and work of a photographer who recognized that human dignity lies at the heart of all great documentary photography. Photographic Equality: Dorothea Lange, Her Migrant Mother, and the Nisei Internees “The cars of the migrant people crawled out of the side roads onto the great cross-country highway, and they took the migrant way to the West. In the daylight they scuttled like bugs to the westward; and as the dark caught them, they clustered like bugs near to shelter and to water. And because they were lonely and perplexed, because they had all come from a place of sadness and worry and defeat, and because they were all going to a mysterious place, they huddled together; they talked together, they shared their lives, their food and the things they hoped for in the new country.” John Steinbeck, The Grapes of Wrath, 1939. Read more in Biography Big things often emerge from small « Machiavelli: Libya’s The Prince Colonel packages, and so it was with Dorothea Muammar Gaddafi » Margaretta Nutzhorn’s life. Dorothea was born into a Lutheran family in the Jewish neighborhood of Hoboken, New http://quazen.com/reference/biography/photographic-equality-dorothea-lange-her-migrant-mother-and-the-nisei-internees/ (1 of 31)10/9/2009 11:23:15 AM Photographic Equality: Dorothea Lange, Her Migrant Mother, and The Nisei Internees | Quazen Jersey, on May 25, 1895. -

Migrant Mother

HITTA HISTORIEN – Det korta 1900-talet DEL 4 Det korta 1900-talet – HITTA HISTORIEN Elevuppgift 4:7 Migrant Mother Grundboken s. 123 Samtidigt som den ekonomiska krisen slog hårt mot möjligheterna att försörja sig, drabbades de stora jordbruksslätterna i amerikanska Mellanvästern under 1930-talet av långvarig torka och sandstormar. I jakten på arbete rörde sig stora skaror av jordbruksarbetare därifrån västerut mot Kalifornien. De bodde i tillfälliga läger och plockade bomull, frukt och grönsaker. På myndigheternas uppdrag dokumenterades levnadsvillkoren i migrantarbetarlägren i Kalifornien, New Mexico och Arizona. Infor- mationen skulle användas som grund för att organisera statliga hjälpin- satser inom the New Deal. Bland annat tog fotografen Dorothea Lange ett stort antal bilder på människor som drabbats av jordbrukskrisen. Särskilt en av hennes bilder har blivit mycket uppmärksammad och gett ett ansikte åt den stora depressionen i USA. Bilden, som kommit att kallas Migrant Mother, förvaras nu i det amerikanska nationalbiblioteket, Library of Con- gress. Där är bilden med fotografens notering, ”Utblottade ärtplockare i Kalifornien; 32 år gammal mor till sju barn. Februari, 1936”, ett av de mest efterfrågade objekten. Dorothea Lange tog sammanlagt sex bilder på ”Migrant Mother”. Förutom till sin uppdragsgivare, regeringen i Washington, lämnade hon fotografier till två dagstidningar som publicerade bilderna och skrev om de svåra förhål- landena. Myndigheterna såg till att en hjälpsändning skickades till lägret. Det sägs även att bilderna -

FIFTY: the Stars, the States, and the Stories

FIFTY: The Stars, the States, and the Stories by Meredith Markow and David Sewell McCann Wisconsin: “Love Finds You” 66 Contents California: “Following Your Friends” 68 Minnesota: “This House” 70 Oregon: “We Will Vote” 72 How to Use Study Pages 3 Kansas: “The Rivalry” 74 Study Pages — Collection One 4 West Virginia: “Follow Your Own Noon” 76 Nevada: “The Telegram” 78 Pennsylvania: “Three Men and a Bell” 7 Nebraska: “Omaha Claim Club” 80 New Jersey: “Miss Barton’s Free School” 9 Colorado: “One Hundred and One Nights” 82 Georgia: “All in Translation” 11 Connecticut: “My Daughter Can” 13 Massachusetts: “The Power of Thanksgiving” 15 Study Pages — Collection Four 84 Maryland: “The Test Oath” 17 North Dakota: “Snow Dancing” 85 South Carolina: “Experiment in Freedom” 19 South Dakota: “Trying to Do Some Good” 87 New Hampshire: “A Meeting on the Green” 21 Montana: “The Marriage Bar” 89 Virginia: “Twigs and Trees” 23 Washington: “Follow the Sun” 92 New York: “All Have Our Part” 25 Idaho: “A Brave Day Indeed” 94 Rhode Island: “The Cohan Family Mirth Makers” 29 Wyoming: “The Golden Rule” 96 Utah: “Eyes of the Earth” 98 Study Pages — Collection Two 31 Oklahoma: “Migrant Mother” 100 New Mexico: “Running for the Rebellion” 102 Vermont: “Gift of the Dragon” 32 Arizona: “Finding Planet X” 104 Kentucky: “Electrification” 34 Alaska: “A Mountain to Conquer” 106 Tennessee: “One of Us” 36 Hawaii: “Queens” 108 Ohio: “The View from Above” 38 Louisiana: “Gumbo and the Petticoat Insurrection” 40 Indiana: “Geodes and Gnomes” 42 Mississippi: “Boll Weevil and the Blues” 44 Illinois: “Crossing the River” 46 Alabama: “It’s Rocket Science” 48 Maine: “From the Ashes” 50 Missouri: “Rainbow Bridge” 52 Arkansas: “Throwing Curve Balls” 54 Michigan: “The Gotham Hotel” 56 Study Pages — Collection Three 59 Florida: “Of Paradise and Peril” 60 Texas: “Natural Beauty” 62 Iowa: “Farmer’s Holiday” 64 FIFTY: The Stars, the States, and the Stories — Study Pages: Table of Contents | sparklestories.com 2 along with their children. -

Dorothea Lange Used Photography to Make an Ugly World Beautiful by Washington Post, Adapted by Newsela Staff on 04.15.20 Word Count 890 Level 830L

Dorothea Lange used photography to make an ugly world beautiful By Washington Post, adapted by Newsela staff on 04.15.20 Word Count 890 Level 830L Image 1. "Migratory Cotton Picker, Eloy, Arizona" (November 1940) by Dorothea Lange. Photo: The Museum of Modern Art, New York Dorothea Lange was an American photographer and photojournalist, best known for her work during the Great Depression. On October 29, 1929, the American stock market crashed. As a result, the economy collapsed. This period of time was called the Great Depression. It lasted until the early 1940s. Banks and businesses closed and more than 15 million Americans became unemployed. To make things worse, in the 1930s, the region known as the Great Plains in the United States, where much of the country's wheat was growing, experienced a drought. The region includes parts of Colorado, Kansas, Texas, Oklahoma and New Mexico. Thousands of people were forced to leave in search of work. The government agency, the Farm Security Administration, hired Lange in 1935 to document this region of the country at this time. An exhibition of Lange's work opened February 9 at the Museum of Modern Art, also called the MoMA, in New York City. The exhibit is titled, "Dorothea Lange: Words & Pictures." Lange's 1940 This article is available at 5 reading levels at https://newsela.com. photograph, titled "Migratory Cotton Picker," opens the exhibition. Poverty And Despair During Depression Lange's most famous photograph, "Migrant Mother," shows a woman who is tired, yet still beautiful. Her beauty is not often remarked on. -

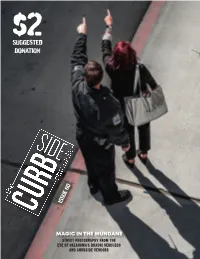

Suggested Donation

$2 SUGGESTED DONATION ISSUE 60 MAGIC IN THE MUNDANE STREET PHOTOGRAPHY FROM THE EYE OF OKLAHOMA’S BHADRI VERDUZCO AND CURBSIDE VENDORS Explore With NEW Arts District | Automobile Alley | Bricktown | City Center | Midtown SEE MORE OF OKLAHOMA CITY BY BIKE FAMILY FUN Myriad Gardens Platform Crystal Bridge, Mo’s Carousel, Children’s Garden & more! $1 to unlock Rides are just 12¢/minute. BIG EVENTS Century Center, Ballpark & Arena Platforms Cox Convention Center, Bricktown Ball Park & Chesepeake Arena Events! Dockless Lock to any DASH friendly bike rack. A NIGHT OUT Automobile Alley & Midtown Platforms Over 20 Bars & Breweries and 65 Restaurants on the Loops! Easy to access Use cash, BCycle app, or key fob. Get Your Ticket to Ride Today! Download Token Transit to get your streetcar Find and Unlock DASH with the App. pass right on your phone. Visit okcstreetcar.com to learn more.. Visit spokiesokc.com/downloads.html Explore With NEW A LETTER FROM THE EDITOR MARCH 2020 Arts District | Automobile Alley | Bricktown | City Center | Midtown >> Nathan Poppe discusses street photography, our reader survey and 4 Angelina Stancampiano shares her a Valentine’s Day flower campaign update passion for nature and how to visit a state park without acting like an animal 6 Then and Now illustrates how far Oklahoma has come and how much SEE MORE OF work needs to be done 9 Curbside vendors used disposable OKLAHOMA CITY BY BIKE cameras in a photo essay focusing on street photography 16 Oklahoma-based street photographer Bhadri Verduzco talks about finding magic in the mundane 22 Help spread the word about Curbside FAMILY FUN and the OKC Day Shelter with shareable Myriad Gardens Platform cut-out cards Crystal Bridge, Mo’s Carousel, Children’s Garden & more! 26 Nazarene Harris explores Dorothea Lange’s “Migrant Mother” and its connection to Oklahoma Curbside vendor Rose holds one of the many bouquets she created for the 2020 Valentine’s Day flower campaign. -

King Kong - It Remains the Subject of Movies and Stories Today

PICTURES BY DOROTHEA LANGE 0. PICTURES BY DOROTHEA LANGE - Story Preface 1. DESPERATE TIMES 2. STARVING PEOPLE 3. PICTURES BY DOROTHEA LANGE 4. THE EMPIRE STATE BUILDING 5. SKULL ISLAND AND DINOSAURS 6. DIGGING FOR DINOSAURS 7. SUE, THE T. REX 8. RAPTORS 9. DINOSAUR FOSSILS 10. GORILLAS This image of Dorothea Lange, cropped from a larger picture, depicts the Resettlement Administration's photographer as she appeared, on the job in California, during February of 1936. Online via the Library of Congress. In the early months of 1936, Florence Owens Thompson (a 32-year-old Oklahoman who had moved to California some years before) was in desperate straits. A widow, she was (at the time) the mother of six. Jim Hill (her companion and acting father to her children) was, among other things, a “peapicker” but was unable to provide for his family since the pea crop had failed. The Thompsons had just sold their tent to buy food. Years later, in 1960, Dorothea Lange described an encounter between the two women which led to Lange’s most famous Farm Administration photographs: I saw and approached the hungry and desperate mother, as if drawn by a magnet. I do not remember how I explained my presence or my camera to her, but I do remember she asked me no questions. I made five exposures, working closer and closer from the same direction. I did not ask her name or her history. She told me her age, that she was thirty-two. She said that they had been living on frozen vegetables from the surrounding fields, and birds that the children killed. -

Iconic Photographs, Unwitting Subjects: Roles of Photography in the Representation of Displaced Persons Within the 2015 European Refugee and Migrant “Crisis”

Iconic Photographs, Unwitting Subjects: Roles of Photography in the Representation of Displaced Persons within the 2015 European Refugee and Migrant “Crisis” Francesca Warley I would like to thank Dr Janna Houwen for her guidance during the writing of this thesis and extend my gratitude to Ish Doney Francesca Warley S2156792 Humanities department, Leiden University Masters in Media Studies, specialisation in Film and Photographic Studies Supervisor: Dr Janna Houwen 5 April 2019 Word count: 20,189 1 The man who finds his homeland sweet is still a tender beginner; he to whom every soil is as his native one is already strong; but he is perfect to whom the entire world is as foreign land Hugo of St. Victor While we live in a time when division is the norm when biases and beliefs seem static and immobile; when hard science is debatable; when journalism is devalued; when humanity is stripped from those in cells, centers and shelters; when it’s all just too much to organise in our head, art calls to the optimism within us and beckons us to breathe Ava DuVernay 2 Table of Contents Introduction 4 Chapter One. Iconic photography, mass media and the refugee as subject 13 1.1.1. From image to icon 13 1.1.2. Iconic photographs of the 20th Century 21 1.2.1. Theories on refugees and migration 28 1.2.2. The refugee as a visual subject 31 1.3.1. Case study: The circulation and appropriation of the Alan Kurdi images 34 1.3.2. Ai Weiwei’s appropriation 41 Chapter Two. -

Art and Social Justice

Art and Social Justice Artists have long used their work to inspire dialogue, of a group of works on the subject of American raise questions, and comment on injustices such independence. Robert Motherwell’s Elegy to the as racism, disenfranchisement, poverty, and war in Spanish Republic 100 uses abstraction to draw their communities and the world at large. The artists viewers’ attention to the tragedy of the Spanish Civil represented in these curriculum materials come from War. a variety of backgrounds and work in a wide range of media. Three are from or worked in Los Angeles. The exception in this group is Juan Patricio Morlete Some artworks, like Jacob Lawrence’s The 1920’s... Ruiz, a Spanish Mexican painter who produced casta The Migrants Arrive and Cast Their Ballots (1974) paintings, which codified the diferent racial mixes and Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother, Nipomo, and resulting social standings of the residents of California (1936), were created specifically to eighteenth century Mexico. Although we cannot know challenge injustice and raise critical consciousness. exactly what Morlete Ruiz had hoped to achieve with Others, like the casta (racial caste) paintings, have these works, it is clear that his goal was not racial come to this role with time and a change in context. equality. Yet when we encounter these paintings Regardless of their original purpose, these artworks now, on the walls of a museum whose staf and can generate conversations about race, civil rights, visitors come from a wide range of backgrounds war, poverty, and the purpose and definition of art. and ethnicities, they can become springboards for The works encourage active looking and critical social justice.