The Minsk Peace: a Critical Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Best of Belarus and the Baltics in 11 Days

THE BEST OF BELARUS AND THE BaLTICS IN 11 DAYS ALL TOURS WITH GUARANTEED www.baltictours.com DEPARTURE! 1 TRAVEL SPECIALISTS Vilnius, Lithuania SINCE 1991 Baltic Tours has been among the ranks of the best for 27 years! Since 2007 Baltic Tours in collaboration with well experienced tourism partners have guaranteed departure tour services offering for over 30 tour programs and more than 300 guaranteed departures per year. Our team believes in the beauty of traveling, in the vibe of adventure and the pleasure of gastronomy. Traveling is a pure happiness - it has become our way of living! I have a degree in tourism management and I encourage our guests to explore the Northeastern region of Europe in its most attractive way. I’ve been working in tourism industry since 2013 and I’m assisting customers from 64 countries. Take a look at my personally selected tours and grab your best deal now! SERVICE STANDARDS MORE VALUE GUARANTEED ESCORTED TOURS QUALITY, SAFETY AND SECURITY SPECIAL FEATURES PRE- AND POST- STAYS www.baltictours.com 3 Kadriorg Park, Tallinn, Estonia JUNE-August, 2021 INCLUDING 11 days/10 nights THE BEST OF TALLINN ● ESTONIA 10 overnight stays at centrally located 4* GBE11: 03 Jun - 13 Jun, 2021 BELARUS AND hotels GBE15: 01 Jul - 11 Jul, 2021 10 x buffet breakfast GBE19: 29 Jul - 08 Aug, 2021 RIGA LATVIA Welcome meeting with champagne-cocktail GBE21: 12 Aug - 22 Aug, 2021 or juice THE BALTICS Personalised welcome package LITHUANIA Entrances to Peter and Paul Church in Vilnius, Rundale Palace and medieval Great Guild IN 11 DAYS VILNIUS Hall in Tallinn MINSK Service of bilingual English-German speaking tour leader on all tours BELARUS Service of 1st class buses or 1st class minivans throughout the itinerary Train tickets Minsk-Vilnius, 2nd class, OW Portage at hotels -Charlotte- National Library of Belarus, Minsk, Belarus “First of all, I would like to say a lot of good words for Rasa. -

Ukraine's Foreign Affairs

No. 2 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, JANUARY 12, 2003 5 2002: THE YEAR IN REVIEW came in a letter to the National Remembrance Institute, and Germany, while meeting in St. Petersburg, signed a Ukraine’s foreign affairs: addressed to a conference being held on the matter. statement of understanding and cooperation on the con- Poland and Ukraine also worked to continue to tinued use of Ukraine’s pipeline for transporting Russian strengthen economic ties in 2002. Poland’s recently natural gas to Germany. pluses and minuses elected Prime Minister Leszek Miller made his first visit The document envisaged European participation in a to Kyiv on February 4 to meet with his Ukrainian coun- multinational consortium that would guarantee the gas kraine’s foreign affairs this past year, like a terpart, Anatolii Kinakh, as well as with President supply. The signing came a day after Presidents Kuchma potluck dinner, consisted of good and bad Kuchma. Talks centered on the Odesa-Brody-Gdansk oil and Putin signed a separate declaration of strategic coop- moments. At the top of a very uneven year in for- pipeline. Prime Minister Miller expressed his full sup- eration in the natural gas sector, which would give eign relations was the Kolchuha affair, which increasing- port for the plan and Poland’s intention to find business Russia joint management and developmental influence ly overshadowed other developments as the year wore U partners to complete the pipeline’s Polish section over the Ukrainian tube in return for its agreement to on. However, even with accusations of President Leonid through to the Baltic seaport city of Gdansk. -

Keeping Gunpowder Dry Minsk Hosts the Council of Defence Ministers of the Commonwealth of Independent States

FOCUS The Minsk Times Thursday, June 13, 2013 3 Keeping gunpowder dry Minsk hosts the Council of Defence Ministers of the Commonwealth of Independent States By Dmitry Vasiliev Minsk is becoming ever more a centre for substantive discussions on integration. Following close on the heels of the Council of CIS Heads of Government and the Forum of Busi- nessmen, Minsk has hosted the CIS Council of Defence Ministers. The President met the heads of delegations before the Council began its work, noting, “We pay special im- portance to each event which helps strengthen the authority of our integra- tion association and further develop co-operation among state-partici- pants in all spheres.” Issues of defence and national security are, naturally, of great importance. The President added, “Bearing in mind today’s dif- ficult geopolitical situation worldwide, this area of integration is of particular importance for state stability and the sustainable development of the Com- monwealth.” Belarus supports the further all- round development of the Common- BELTA Prospective issues of co-operation discussed in Minsk at meeting of Council of CIS Defence Ministers wealth, strengthening its defence capa- bility and authority: a position shared any independence... We, Belarusians mark event in the development of close the military sphere is a component of sites in Russia and Kazakhstan and an by many heads of state considering and Russians, don’t have any secrets partnerships in the military sphere. integration, with priorities defined by international competition for the pro- integration. The President emphasised, from each other. If we don’t manage to Last year, the CIS Council of De- the concerns of friendly countries re- fessional military is planned: Warriors “Whether we like it or not, life forces achieve anything (Russia also has prob- fence Ministers — a high level inter- garding sudden complications in the of the Commonwealth. -

The Travel Guide

Travel 1. Arriving by airplane Minsk National Airport (MSQ) There are several Airlines that operate at Minsk National Airport, such as Belavia, Aeroflot, Airbaltic and Lufthansa. The airport is about 50 km from Minsk. An alternative low-budget connection to Minsk is to fly to Vilnius International Airport (VNO) and take the train from Vilnius to Minsk. Several low-cost airlines operate at Vilnius International Airport. The Vilnius International airport is about 200 km from Minsk and train are frequently operating between Minsk and Vilnius (see information below). Important! If you will choose this option you need to have a valid visa or a valid passport allowing to stay visa-free in Belarus. Information about visa process is in General information. Transport from the airport (MSQ) to the Minsk Central station (Minsk Tsentralnyi) Minsk Tsentralnyi is a bus stop near Minsk Central Train station (Babrujskaja 6). By bus: BUS № 300Э You can buy a ticket via the ticket machine at the airport, at the bus station by credit card, from a ticket agent at the bus stop or from bus driver by cash (BYN only). You can exchange money at the airport. The bus stop is located in front of Gate 5-6 (arrival hall). Journey time: 1 hour. Bus timetable: From National Airport Minsk (MSQ) to Minsk Central (Minsk Tsentralnyi) 4:50, 6:25, 7:20, 8:00, 9:00, 9:40, 10:20, 11:20, 12:00, 12:40, 13:20, 14:20, 15:00, 15:40, 16:20, 17:00, 17:40, 18:20, 19:00, 20:00, 20:40, 21:20, 22:05, 23:00, 00:05, 1:45, 3:15 By taxi: You can pay by credit card and order taxi online. -

Note N°57/20 Russia's Policy Towards Belarus During Alyaksandr

Note n°57/20 August 3, 2020 Milàn Czerny Graduated from the Department of War Studies, King’s College London Analyst – Le Grand Continent (GEG), Paris Russia’s policy towards Belarus during Alyaksandr Lukashenka’s fifth presidential term Introduction Belarus and Ukraine compose the core of the « Russian world » (Russkiy Mir), a geopolitical and ideologically constructed space centered around Moscow and based on common civilizational, historical, linguistic, and spiritual ties between the three countries1. Russia’s depiction of this space as a united whole has been deeply shattered since 2014 and the beginning of the war in Ukraine opposing Russian-backed rebels to Ukrainian forces. In this context, Belarus holds a significant symbolic and strategic value for Russia’s policy towards post-Soviet states. Indeed, because of the close historical and civilizational ties between Russia and Belarus, the Belarusian president, Alyaksandr Lukashenka, is a show-case ally necessary for Moscow’s status as a regional leader in the post-Soviet space2. Despite some tensions between Russia and Belarus in the 2000s, for instance around trade issues in 2009, a bargain was established between the two 1 Vladimir Putin has put forward the concept of « Russian world » during his second presidential term (2004-2008) with the support of the Russian Orthodox Church with a view to stressing the ties between Russia and its neighbors based on an essentialist representation of Russian language and culture. The concept serves to legitimize Russian foreign policy toward Ukraine and Belarus by relativizing the borders between the three state and stress Russia’s role as a « natural » leader in the region. -

List of Persons and Entities Under EU Restrictive Measures Over the Territorial Integrity of Ukraine

dhdsh PRESS Council of the European Union EN 1st December 2014 List of persons and entities under EU restrictive measures over the territorial integrity of Ukraine List of persons N. Name Identifying Reasons Date of information listing 1. Sergey Valeryevich d.o.b. 26.11.1972 Aksyonov was elected “Prime Minister of Crimea” in the Crimean Verkhovna Rada on 27 17.3.2014 Aksyonov February 2014 in the presence of pro-Russian gunmen. His “election” was decreed unconstitutional by Oleksandr Turchynov on 1 March. He actively lobbied for the “referendum” of 16 March 2014. 2. Vladimir Andreevich d.o.b. 19.03.1967 As speaker of the Supreme Council of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, Konstantinov 17.3.2014 Konstantinov played a relevant role in the decisions taken by the Verkhovna Rada concerning the “referendum” against territorial integrity of Ukraine and called on voters to cast votes in favour of Crimean Independence. 3. Rustam Ilmirovich d.o.b. 15.08.1976 As Deputy Chairman of the Council of Ministers of Crimea, Temirgaliev played a relevant role 17.3.2014 Temirgaliev in the decisions taken by the Verkhovna Rada concerning the “referendum” against territorial integrity of Ukraine. He lobbied actively for integration of Crimea into the Russian Federation. 4. Deniz Valentinovich d.o.b. 15.07.1974 Berezovskiy was appointed commander of the Ukrainian Navy on 1 March 2014 and swore an 17.3.2014 Berezovskiy oath to the Crimean armed force, thereby breaking his oath. The Prosecutor-General’s Office of Ukraine launched an investigation against him for high treason. -

THE BALTICS Oct 22 - Nov 4, 2015

Join Rabbi Stephanie Bernstein & Temple Rodef Shalom on a Jewish Heritage tour of THE BALTICS Oct 22 - Nov 4, 2015 This amazing tour includes... 3 nights at the Radisson Blue Hotel in Riga 2 nights at Park Inn Radisson in Kaunus 2 nights at the Kempinski Hotel in Vilnius 5 nights at the Renaissance Hotel in Minsk Breakfast daily Old Riga Shabbat dinner in Riga Shabbat dinner & farewell dinner in Minsk Arrival & departure transfers with main group Entrance fees & porterage per itinerary Touring in a deluxe air-conditioned vehicle Vilnius Expert English-speaking guide throughout MInsk On This Outstanding Journey, together we will… Explore the Jewish Heritage story and enrich our knowledge of Jewish History in Riga, Kaunus, Vilnius & Minsk. Experience all that the Baltics have to offer. Confront the stories of the past and celebrate the re-birth of the communities of today and tomorrow in the region. Complete attached registration or register online at: www.ayelet.com P 800-237-1517 • F 518-783-6003 www.ayelet.com/BernsteinOct2015.aspx 19 Aviation Rd., Albany, NY 12205 ® On our adventure together, we will... • Visit the important historical places of Riga’s Jewish community including the museum “Jews in Latvia” and places of commemoration of the holocaust of World War II, Bikernieki and Salaspils • Enjoy the splendors of the Dome Cathedral, the Castle of Riga & St. Peter’s Church • Tour Slobodka, a Jewish suburb of pre-war Kaunas and the site of the ghetto during WWII TOUR PRICING Full Discounted Price per person • See the home of Leah Goldberg -

17 February 2015 1 List of Individuals Subject to Eu

17 FEBRUARY 2015 1 LIST OF INDIVIDUALS SUBJECT TO EU SANCTIONS (ASSET FREEZE) BASED ON COUNCIL REGULATION 208/2014 AS AMENEDED BY REGULATIONS 381/2014 AND 138/2015 1.1 Regulation 208/2014, published 6 March 2014 1. Viktor Fedorovych Yanukovych, former President of Ukraine (6 March 2014) 2. Vitalii Yuriyovych Zakharchenko, former Minister of Internal Affairs (6 March 2014) 3. Viktor Pavlovych Pshonka, former Prosecutor General of Ukraine (6 March 2014) 4. Oleksandr Hryhorovych Yakymenko, former Head of Security Service of Ukraine (6 March 2014) 5. Andriy Volodymyrovych Portnov, former Adviser to the President of Ukraine (6 March 2014) 6. Olena Leonidivna Lukash, former Minister of Justice (6 March 2014) 7. Andrii Petrovych Kliuiev, former Head of Administration of President of Ukraine (6 March 2014) 8. Viktor Ivanovych Ratushniak, former Deputy Minister of Internal Affairs (6 March 2014) 9. Oleksandr Viktorovych Yanukovych, son of former President, businessman (6 March 2014) 10. Viktor Viktorovych Yanukovych, son of former President, Member of the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine (6 March 2014) 11. Artem Viktorovych Pshonka, son of former Prosecutor General, Deputy Head of the faction of Party of Regions in the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine (6 March 2014) 12. Serhii Petrovych Kliuiev, businessman, brother of Mr. Andrii K1iuiev (6 March 2014) 13. Mykola Yanovych Azarov, Prime Minister of Ukraine until January 2014 (6 March 2014) 14. Oleksii Mykolayovych Azarov, son of former Prime Minister Azarov (6 March 2014) 15. Serhiy Vitaliyovych Kurchenko, businessman (6 March 2014) 16. Dmytro Volodymyrovych Tabachnyk, former Minister of Education and Science (6 March 2014) 17. Raisa Vasylivna Bohatyriova, former Minister of Health (6 March 2014) 18. -

Colliers CEE Report

EX DING BORDERS OFFICE MARKET IN 15 CEE COUNTRIES October 2019 OFFICE MARKET IN 15 CEE COUNTRIES INTRODUCTION CONTENTS 2 Welcome to our publication about the office sector in Central and Eastern Europe. The report presents the situation in the office markets in 15 CEE countries (Albania, Belarus, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czechia, Estonia, INTRODUCTION Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia and Ukraine). In the study, we focused on key market indicators such as total office stock, take-up and leasing conditions, vacancy levels, space under construction and a forecast for the upcoming years. The presentation of the office market in each country is also enriched with a short commentary, an interesting fact from the market and photos of modern office projects. 4-5 The report has been divided into 3 parts: • A map presenting 15 CEE countries with key economic data; ECONOMIC DATA • The comparative part, where on aggregated charts we present H1 2019 office market data for 15 CEE countries; • Presentation of the office market in each country. In recent years, the CEE region has been characterized by dynamic development, which goes hand in hand with the growth of modern office projects. We forecast that by 2021 the total office stock in the 2 6-7 15 CEE countries will exceed 30 million m . More and more office buildings can boast of prestigious certificates, modern technological and environmental solutions or an innovatively designed space. OFFICE MARKET We believe that thanks to this publication the potential of the 15 CEE countries will be rediscovered IN 15 CEE COUNTRIES IN H1 2019 and will be further developed. -

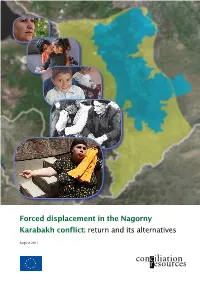

Forced Displacement in the Nagorny Karabakh Conflict: Return and Its Alternatives

Forced displacement in the Nagorny Karabakh conflict: return and its alternatives August 2011 conciliation resources Place-names in the Nagorny Karabakh conflict are contested. Place-names within Nagorny Karabakh itself have been contested throughout the conflict. Place-names in the adjacent occupied territories have become increasingly contested over time in some, but not all (and not official), Armenian sources. Contributors have used their preferred terms without editorial restrictions. Variant spellings of the same name (e.g., Nagorny Karabakh vs Nagorno-Karabakh, Sumgait vs Sumqayit) have also been used in this publication according to authors’ preferences. Terminology used in the contributors’ biographies reflects their choices, not those of Conciliation Resources or the European Union. For the map at the end of the publication, Conciliation Resources has used the place-names current in 1988; where appropriate, alternative names are given in brackets in the text at first usage. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of Conciliation Resources or the European Union. Altered street sign in Shusha (known as Shushi to Armenians). Source: bbcrussian.com Contents Executive summary and introduction to the Karabakh Contact Group 5 The Contact Group papers 1 Return and its alternatives: international law, norms and practices, and dilemmas of ethnocratic power, implementation, justice and development 7 Gerard Toal 2 Return and its alternatives: perspectives -

Religion and Denominations in the Republic of Belarus

November 2011 Religion and denominations in the Republic of Belarus Multi-confessional structure of the Belarusian society has been forming over more than a thousand year history of the nation; it became an important factor that had a great influence on the formation of culture, mentality and state traditions of the present-day Belarus. The experience of our state, where more than 25 different denominations and religious movements organically coexist, is unique. The Orthodox Church has been of great 58.9 per cent of Belarusians consider importance on the Belarusian lands themselves believers. 82 per cent of since the adoption of Christianity in them are Orthodox, 12 per cent are the 10th century and today still attracts Roman Catholic and 6 per cent are a significant number of representatives of other believers. Four 58,9 % denominations. centuries later the of Belarusians are Catholic Church believers. 82 % of them are In the 16th came to the orthodox, 12 % are catholics, century the Grand Duchy E u r o p e a n of Lithuania that 6% represent other Reformation was created on the denominations resulted in the basis of the Belarusian arrival of Protestant territory. Since that time Catholicism movements, among which Lutheran made a great contribution to the and Calvinist ideas became widespread culture of Belarus and its history. on the territory of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Even earlier, at the end of Protestant religious organizations the 14th -15th centuries, Muslims and are represented by 1005 religious Jews settled in Belarus. A large number communities, 21 associations, of religious denominations appeared 22 missions and 5 religious during the 20th century. -

Macrofungi of Nakhchivan (Azerbaijan) Autonomous Republic

Turk J Bot 36 (2012) 761-768 © TÜBİTAK Research Article doi:10.3906/bot-1101-43 Macrofungi of Nakhchivan (Azerbaijan) Autonomous Republic Hamide SEYİDOVA1, Elşad HÜSEYİN2,* 1 Institute of Bioresources, Nakhchivan Section of the National Academy of Sciences of Azerbaijan, AZ 7000, Babek st. 10, Nakhchivan - AZERBAIJAN 2 Department of Biology, Arts and Sciences Faculty, Ahi Evran University, Kırşehir - TURKEY Received: 27.01.2011 ● Accepted: 16.04.2012 Abstract: In this article, an attempt has been made to establish the species composition of the macrofungi of Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic of Azerbaijan. A total of 73 species of macromycetes were registered, 2 belonging to the division Ascomycota and 71 to the division Basidiomycota. The trophic structure for the fungal species is as follows: 22 lignicolous and 51 terricolous. Fifty-three species were added to the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic mycobiota; 8 species of them were added to the mycobiota of Azerbaijan as new records. Key words: Macrofungi, new record, Nakhchivan, Azerbaijan Introduction °C in January and 41-43 °C in July-August. Relative Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic (AR) is a part of humidity varies in different parts of the republic. In the Azerbaijan Republic. It is located in the south- the city of Nakhchivan it is 74%-76% in December- western part of the Lesser Caucasus Mountains. The February and 39%-40% in July-August. In the middle total length of the republic’s border is 398 km. The mountain zone it is 69%-78% and 52%-55% in region covers 5363 km2 and borders Armenia (221 December-February and July-August, respectively, km) to the east and north, Iran (179 km) to the south which is similar to the foothills of the Lesser Caucasus.