A Movement Moves . . . Is There a Women's Movement in England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Host's Master Artist List for Game 1

Host's Master Artist List for Game 1 You can play the list in the order shown here, or any order you prefer. Tick the boxes as you play the songs. Louis Armstrong Kate Nash Sonny & Cher Matt Cardle Animals Cliff Richard Manfred Mann Craid David Petula Clark Ray Charles Roy Orbison HearSay Kings Of Leon Ne-Yo Jamelia Shayne Ward Holly Valance Georgie Fame Bobby Darin Paul Weller Vengaboys Scouting For Girls Cilla Black Avicii Beach Boys Spencer Davis Group Blue Plan B Kelly Clarkson Britney Spears Queen Basshunter Black Eyed Peas Bobby Vee Freda Payne Doobie Brothers Gerry & The Pacemakers Marmalade Doris Day JLS Evanescence Katy Perry Christina Aguilera Ronetts Anastacia Liberty X James Morrison Jeff Beck Snoop Dogg Chubby Checker Copyright QOD Page 1/28 Host's Master Artist List for Game 2 You can play the list in the order shown here, or any order you prefer. Tick the boxes as you play the songs. Smokey Robinson Lovin' Spoonfull Troggs Ben Heanow Dion Warwick Avons James Brown Snow Patrol Little Richard Diana Ross Ronetts Tom Jones Dean Martin Gladys Knight Estelle Kid Rock Evanescence Mamas & The Papas Fats Domino Lulu Anastacia Good Charlotte Craid David Coral Ne-Yo Emili Sande Mumford & Son Lenny Kravitz Fatboy Slim Justin Timberlake Lily Allen Doris Day Spencer Davis Group Who Stevie Wonder Queen KT Tunstall Scissor Sisters Buddy Holly Nickelback Shayne Ward Kinks Brenda Lee Andy Williams Holly Valance Temptations Searchers Britney Spears Shirley Bassey The Fray Copyright QOD Page 2/28 Host's Master Artist List for Game 3 You can play the list in the order shown here, or any order you prefer. -

Young Feminist Activists in Present-Day China: a New Feminist Generation?

China Perspectives 2018/3 | 2018 Twenty Years After: Hong Kong's Changes and Challenges under China's Rule Young Feminist Activists in Present-Day China: A New Feminist Generation? Qi Wang Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/8165 ISSN: 1996-4617 Publisher Centre d'étude français sur la Chine contemporaine Printed version Date of publication: 1 September 2018 Number of pages: 59-68 ISSN: 2070-3449 Electronic reference Qi Wang, « Young Feminist Activists in Present-Day China: A New Feminist Generation? », China Perspectives [Online], 2018/3 | 2018, Online since 01 September 2019, connection on 28 October 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/8165 © All rights reserved Articles China perspectives Young Feminist Activists in Present-Day China A New Feminist Generation? QI WANG ABSTRACT: This article studies post-2000 Chinese feminist activism from a generational perspective. It operationalises three notions of gene- ration—generation as an age cohort, generation as a historical cohort, and “political generation”—to shed light on the question of generation and generational change in post-socialist Chinese feminism. The study shows how the younger generation of women have come to the forefront of feminist protest in China and how the historical conditions they live in have shaped their feminist outlook. In parallel, it examines how a “po- litical generation” emerges when feminists of different ages are drawn together by a shared political awakening and collaborate across age. KEYWORDS: -

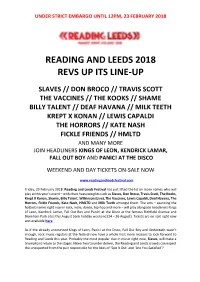

Reading and Leeds 2018 Revs up Its Line-Up

UNDER STRICT EMBARGO UNTIL 12PM, 23 FEBRUARY 2018 READING AND LEEDS 2018 REVS UP ITS LINE-UP SLAVES // DON BROCO // TRAVIS SCOTT THE VACCINES // THE KOOKS // SHAME BILLY TALENT // DEAF HAVANA // MILK TEETH KREPT X KONAN // LEWIS CAPALDI THE HORRORS // KATE NASH FICKLE FRIENDS // HMLTD AND MANY MORE JOIN HEADLINERS KINGS OF LEON, KENDRICK LAMAR, FALL OUT BOY AND PANIC! AT THE DISCO WEEKEND AND DAY TICKETS ON-SALE NOW www.readingandleedsfestival.com Friday, 23 February 2018: Reading and Leeds Festival has just lifted the lid on more names who will play at this year’s event – with chart heavyweights such as Slaves, Don Broco, Travis Scott, The Kooks, Krept X Konan, Shame, Billy Talent, Wilkinson (Live), The Vaccines, Lewis Capaldi, Deaf Havana, The Horrors, Fickle Friends, Kate Nash, HMLTD and Milk Teeth amongst them. The acts – spanning the hottest names right now in rock, indie, dance, hip-hop and more – will play alongside headliners Kings of Leon, Kendrick Lamar, Fall Out Boy and Panic! at the Disco at the famous Richfield Avenue and Bramham Park sites this August bank holiday weekend (24 – 26 August). Tickets are on-sale right now and available here. As if the already announced Kings of Leon, Panic! at the Disco, Fall Out Boy and Underøath wasn’t enough, rock music regulars at the festival now have a whole host more reasons to look forward to Reading and Leeds this year. Probably the most popular duo in music right now, Slaves, will make a triumphant return to the stages. Never two to under deliver, the Reading and Leeds crowds can expect the unexpected from the pair responsible for the likes of ‘Spit It Out’ and ‘Are You Satisfied’? UNDER STRICT EMBARGO UNTIL 12PM, 23 FEBRUARY 2018 With another top 10 album, ‘Technology’, under their belt, Don Broco will be joining the fray this year. -

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. May 21, 2018 to Sun. May 27, 2018 Monday

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. May 21, 2018 to Sun. May 27, 2018 Monday May 21, 2018 5:00 PM ET / 2:00 PM PT 8:00 AM ET / 5:00 AM PT Steve Winwood Nashville A smooth delivery, high-spirited melodies, and a velvet voice are what Steve Winwood brings When You’re Tired Of Breaking Other Hearts - Rayna tries to set the record straight about her to this fiery performance. Winwood performs classic hits like “Why Can’t We Live Together”, failed marriage during an appearance on Katie Couric’s talk show; Maddie tells a lie that leads to “Back in the High Life” and “Dear Mr. Fantasy”, then he wows the audience as his voice smolders dangerous consequences; Deacon is drawn to a pretty veterinarian. through “Can’t Find My Way Home”. 9:00 AM ET / 6:00 AM PT 6:00 PM ET / 3:00 PM PT The Big Interview Foreigner Phil Collins - Legendary singer-songwriter Phil Collins sits down with Dan Rather to talk about Since the beginning, guitarist Mick Jones has led Foreigner through decades of hit after hit. his anticipated return to the music scene, his record breaking success and a possible future In this intimate concert, listen to fan favorites like “Double Vision”, “Hot Blooded” and “Head partnership with Adele. Games”. 10:00 AM ET / 7:00 AM PT 7:00 PM ET / 4:00 PM PT Presents Phil Collins - Going Back Fleetwood Mac, Live In Boston, Part One Filmed in the intimate surroundings of New York’s famous Roseland Ballroom, this is a real Mick, John, Lindsey, and Stevie unite for a passionate evening playing their biggest hits. -

Nash, Kate. 2018. Film That Brings Human Rights to Life. Public Culture, 30(3), Pp

Nash, Kate. 2018. Film That Brings Human Rights to Life. Public Culture, 30(3), pp. 393-412. ISSN 0899-2363 [Article] https://research.gold.ac.uk/id/eprint/20620/ The version presented here may differ from the published, performed or presented work. Please go to the persistent GRO record above for more information. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Goldsmiths, University of London via the following email address: [email protected]. The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. For more information, please contact the GRO team: [email protected] To be published in Public Culture Film that brings human rights to life (1) Kate Nash In this article I explore what feature-length films of the kind that are shown in human rights film festivals contribute to human rights culture. Analysing films that feature victims (including, in some detail, Sonita) and perpetrators (notably The Act of Killing), I argue that a viewer is called on to identify with the protagonist who drives forward a narrative of self- responsibilisation – regardless of any commitment s/he may make then to either organised political action or to ethical deconstruction of a film’s narrative. It is principally through work on the self to become a subject of human rights that human rights films are contributing to human rights culture – in advance of a global community of citizens and institutions that might regularly and routinely secure human rights for all. The aim of this article is to explore how the narratives of feature length films shown in human rights film festivals are contributing to human rights culture. -

(You Gotta) Fight for Your Right (To Party!) 3 AM ± Matchbox Twenty. 99 Red Ballons ± Nena

(You Gotta) Fight For Your Right (To Party!) 3 AM ± Matchbox Twenty. 99 Red Ballons ± Nena. Against All Odds ± Phil Collins. Alive and kicking- Simple minds. Almost ± Bowling for soup. Alright ± Supergrass. Always ± Bon Jovi. Ampersand ± Amanda palmer. Angel ± Aerosmith Angel ± Shaggy Asleep ± The Smiths. Bell of Belfast City ± Kristy MacColl. Bitch ± Meredith Brooks. Blue Suede Shoes ± Elvis Presely. Bohemian Rhapsody ± Queen. Born In The USA ± Bruce Springstein. Born to Run ± Bruce Springsteen. Boys Will Be Boys ± The Ordinary Boys. Breath Me ± Sia Brown Eyed Girl ± Van Morrison. Brown Eyes ± Lady Gaga. Chasing Cars ± snow patrol. Chasing pavements ± Adele. Choices ± The Hoosiers. Come on Eileen ± Dexy¶s midnight runners. Crazy ± Aerosmith Crazy ± Gnarles Barkley. Creep ± Radiohead. Cupid ± Sam Cooke. Don¶t Stand So Close to Me ± The Police. Don¶t Speak ± No Doubt. Dr Jones ± Aqua. Dragula ± Rob Zombie. Dreaming of You ± The Coral. Dreams ± The Cranberries. Ever Fallen In Love? ± Buzzcocks Everybody Hurts ± R.E.M. Everybody¶s Fool ± Evanescence. Everywhere I go ± Hollywood undead. Evolution ± Korn. FACK ± Eminem. Faith ± George Micheal. Feathers ± Coheed And Cambria. Firefly ± Breaking Benjamin. Fix Up, Look Sharp ± Dizzie Rascal. Flux ± Bloc Party. Fuck Forever ± Babyshambles. Get on Up ± James Brown. Girl Anachronism ± The Dresden Dolls. Girl You¶ll Be a Woman Soon ± Urge Overkill Go Your Own Way ± Fleetwood Mac. Golden Skans ± Klaxons. Grounds For Divorce ± Elbow. Happy ending ± MIKA. Heartbeats ± Jose Gonzalez. Heartbreak Hotel ± Elvis Presely. Hollywood ± Marina and the diamonds. I don¶t love you ± My Chemical Romance. I Fought The Law ± The Clash. I Got Love ± The King Blues. I miss you ± Blink 182. -

Colorado Law Scholarly Commons Neofeminism

University of Colorado Law School Colorado Law Scholarly Commons Articles Colorado Law Faculty Scholarship 2013 Neofeminism Aya Gruber University of Colorado Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.law.colorado.edu/articles Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Family Law Commons, Jurisprudence Commons, Law and Gender Commons, and the Law and Race Commons Citation Information Aya Gruber, Neofeminism, 50 HOUS. L. REV. 1325 (2013), available at https://scholar.law.colorado.edu/ articles/439. Copyright Statement Copyright protected. Use of materials from this collection beyond the exceptions provided for in the Fair Use and Educational Use clauses of the U.S. Copyright Law may violate federal law. Permission to publish or reproduce is required. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Colorado Law Faculty Scholarship at Colorado Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of Colorado Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. +(,121/,1( Citation: 50 Hous. L. Rev. 1325 2012-2013 Provided by: William A. Wise Law Library Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline Mon May 1 11:29:39 2017 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: Copyright Information ARTICLE NEOFEMINISM Aya Gruber* ABSTRACT Today it is prosaic to say that "feminism is dead." Far from being moribund, feminist legal theory is breaking from its somewhat dogmatic past and forging ahead with new vigor. -

Everyday Feminism in the Digital Era: Gender, the Fourth Wave, and Social Media Affordances

EVERYDAY FEMINISM IN THE DIGITAL ERA: GENDER, THE FOURTH WAVE, AND SOCIAL MEDIA AFFORDANCES A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Urszula M. Pruchniewska May 2019 Examining Committee Members: Carolyn Kitch, Advisory Chair, Media and Communication Fabienne Darling-Wolf, Media and Communication Adrienne Shaw, Media and Communication Rebecca Alpert, Religion ABSTRACT The last decade has seen a pronounced increase in feminist activism and sentiment in the public sphere, which scholars, activists, and journalists have dubbed the “fourth wave” of feminism. A key feature of the fourth wave is the use of digital technologies and the internet for feminist activism and discussion. This dissertation aims to broadly understand what is “new” about fourth wave feminism and specifically to understand how social media intersect with everyday feminist practices in the digital era. This project is made up of three case studies –Bumble the “feminist” dating app, private Facebook groups for women professionals, and the #MeToo movement on Twitter— and uses an affordance theory lens, examining the possibilities for (and constraints of) use embedded in the materiality of each digital platform. Through in-depth interviews and focus groups with users, alongside a structural discourse analysis of each platform, the findings show how social media are used strategically as tools for feminist purposes during mundane online activities such as dating and connecting with colleagues. Overall, this research highlights the feminist potential of everyday social media use, while considering the limits of digital technologies for everyday feminism. This work also reasserts the continued need for feminist activism in the fourth wave, by showing that the material realities of gender inequality persist, often obscured by an illusion of empowerment. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

PRESSEMITTEILUNG 27.03.2017 Kate Nash Kommt Im August Auf

FKP Scorpio Konzertproduktionen GmbH Große Elbstr. 277 a ∙ 22767 Hamburg Tel. (040) 853 88 888 ∙ www.fkpscorpio.com PRESSEMITTEILUNG 27.03.2017 Kate Nash kommt im August auf „Made Of Bricks“-Jubiläumstour Wenn das kein Grund zum Feiern ist: Vor zehn Jahren kam ein Album heraus, das die Musikszene in Großbritannien nachhaltig veränderte: Durch „Made Of Bricks“, die platinveredelte Debütplatte von Kate Nash, war klar geworden, dass sich junge Frauen ihren Platz in der Gesellschaft (und in der Musikindustrie) ganz anders behaupten wollen. Eine neue Art von Feminismus hielt Einzug. Gleichzeitig war Nash auch eines der ersten so genannten Internetphänomene. Durch ihre auf Myspace veröffentlichten Lieder wie „Caroline’s A Victim“ wurde sie rasend schnell bekannt - und „Foundations“, die erste Single aus dem Album, ging komplett durch die Decke. Weil ihre Fans schon alle Türen einrannten, musste „Made Of Bricks“ sogar fünf Wochen vor dem geplanten Termin veröffentlicht werden. „Ich fühle mich wie eine Außenseiterin, die sich gerade irgendwo reingeschlichen hat“, sagte die junge Frau damals. Inzwischen ist es zwar noch immer nicht Standard, aber doch sehr viel selbstverständlicher geworden, dass Frauen ihre Songs selbst schreiben, ihre Instrumente selbst spielen, die Kontrolle über ihre Musik weitgehend in ihren eigenen Händen halten. Ganz schön stark für eine 20-Jährige, die im Anschluss nicht nur aus dem Stand den Brit-Award als British Female Solo Artist und etliche weitere Auszeichnungen abräumte, sondern auch weiterhin sehr erfolgreich Musik macht. Darüber hinaus engagiert sie sich sozial: Sie rief gemeinsam mit Billy Bragg, Blur, Radiohead und anderen Künstlern die Featured Artists Coalition ins Leben, die sich für die Rechte von Musikern im digitalen Zeitalter einsetzt. -

Feminism 2.0 Tammy Bruce

FEMINISM 2.0 TAMMY BRUCE I want to talk to you about a new feminism for the 21st century. There are three pillars to this new feminism: Dignity. The word “no.” And men. That’s right, men. But before I expound on these three ideas, you need to know something about me. I was very involved in the feminist movement, including being on the board of directors of the National Organization for Women. For this I feel much pride and some guilt. Pride because feminism has pushed forward some very important and needed changes; and guilt because it has also done a lot of damage. My work now is to reverse that damage. So in that spirit, let’s talk about the first pillar of this new feminism: dignity. Dignity is at the core of what feminism should always be about. Dignity means that a woman should be able to freely choose her own path in life. That’s what feminism once held. But does it still? Ask almost any female college student today what she aspires to be and she’ll list any number of career choices. The one she won’t list is wife and mother. In fact any time someone has the temerity to suggest that a woman might want to look for a husband while in college, as a very successful Princeton grad recently did in a letter to the school’s newspaper, feminists go nuts. A new feminism will value and respect all responsible choices. And while we’re talking about dignity, I can’t think of anything less dignified for women than the feminist belief that in the sexual arena, women are like, and therefore ought to act like, men.