Videos on Tiktok and What They Tell Us About the Digital Self J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Consolidated National Subscription TV Share and Reach National Share and Reach Report

Consolidated National Subscription TV Share and Reach National Share and Reach Report - Subscription TV Homes only Week 28 2021 (04/07/2021 - 10/07/2021) 18:00 - 23:59 Total Individuals - Including Guests Channel Share Of Viewing Reach Weekly 000's % TOTAL PEOPLE ABC TV 5.3 1486 ABC Kids/ABC TV Plus 0.8 618 ABC ME 0.2 156 ABC NEWS 0.7 522 Seven + AFFILIATES 16.0 2619 7TWO + AFFILIATES 1.4 537 7mate + AFFILIATES 1.3 742 7flix + AFFILIATES 0.5 423 Nine + AFFILIATES* 19.0 2978 GO + AFFILIATES* 0.9 628 Gem + AFFILIATES* 1.8 859 9Life + AFFILIATES* 0.5 275 9Rush + AFFILIATES* 0.2 133 10 + AFFILIATES* 6.7 1840 10 Bold + AFFILIATES* 1.3 377 10 Peach + AFFILIATES* 1.1 556 10 Shake + AFFILIATES* 0.1 147 Sky News on WIN + AFFILIATES* 0.2 187 SBS 3.8 1176 SBS VICELAND 0.5 520 SBS Food 0.3 381 NITV 0.1 159 SBS World Movies 0.3 329 A&E 0.4 289 A&E+2 0.1 158 Animal Planet 0.3 214 BBC Earth 0.3 248 BBC First 0.3 263 beIN SPORTS 1 0.0 89 beIN SPORTS 2 0.0 51 beIN SPORTS 3 0.0 76 Boomerang 0.2 69 BoxSets 0.0 61 Cartoon Network 0.0 31 CBeebies 0.1 131 Club MTV 0.0 88 CMT 0.0 65 crime + investigation 0.7 277 Discovery Channel 1.1 605 Discovery Channel+2 0.2 226 Discovery Turbo 0.3 205 Discovery Turbo+2 0.1 141 DreamWorks 0.0 39 E! 0.2 212 E! +2 0.0 146 ESPN 0.1 225 ESPN2 0.1 159 FOX Arena 0.5 410 FOX Arena+2 0.1 113 FOX Classics 1.0 478 FOX Classics+2 0.2 213 Excludes Tasmania *Affiliation changes commenced July 1, 2021. -

Foxtel in 2016

Media Release: Thursday November 5, 2015 Foxtel in 2016 In 2016, Foxtel viewers will see the return of a huge range of their favourite Australian series, with the stellar line-up bolstered by a raft of new commissions and programming across drama, lifestyle, factual and entertainment. Foxtel Executive Director of Television Brian Walsh said: “We are proud to announce the re- commission of such an impressive line-up of our returning Australian series, which is a testament to our production partners, creative teams and on air talent. In 2016, our subscribers will see all of their favourite Australian shows return to Foxtel, as well as new series we are sure will become hits with our viewers. “Our growing commitment to producing exclusive home-made signature programming for our subscribers will continue in 2016, with more Australian original series than ever before. Our significant investment in acquisitions will also continue, giving Foxtel viewers the biggest array of overseas series available in Australia. “In 2016 we will make it even easier for our subscribers to enjoy Foxtel. Our on demand Foxtel Anytime offering will continue to be the driving force behind the most comprehensive nationwide streaming service available to all customers as part of their package. Over the next year, Foxtel will provide its subscribers with more than 16,000 hours of programming, available anytime.” “To complement our outstanding on demand offering, our Box Sets channel is designed for our binge- watching viewers who want to watch or record full series of their favourite shows from Australia and around the world. It’s the only channel of its kind in our market and content on Box Sets will also increase next year, giving our subscribers even more freedom to watch what they want, when they want.” “Foxtel also continues to be the best movies destination in Australia. -

OAKS MELBOURNE SOUTHBANK SUITES WELCOME TOUR DESK INTERCOM TELEVISION CHANNELS Welcome to Oaks Melbourne Southbank Suites

GUEST SERVICES DIRECTORY OAKS MELBOURNE SOUTHBANK SUITES WELCOME TOUR DESK INTERCOM TELEVISION CHANNELS Welcome to Oaks Melbourne Southbank Suites. Following, you Our team can assist you with booking tours and attractions around An intercom panel at the residence entry is connected to every room Local Free to Air channels are available on your television and will find information with respect to the building and surrounds. Melbourne. Please contact reception for recommendations. by their own in-room intercom. Outside visitors can contact guests are free of charge to view. For Free to Air channels, choose DTV If we have omitted any details, please feel free to approach our directly by simply keying in the room number followed by the bell Source/Input. friendly reception staff either in person or by dialing ‘9’ from your FAX / EMAIL / PRINTING button. To open external doors for visitors, press the door release key To access the Foxtel channels please use the Source/ Input button cordless in-room phone located beside our televisions. We trust The hotel fax number is 03 8548 4299 and the reception email is button followed by ( ) button on the intercom phone attached to the ° and choose HDMI 2. that your stay with us will be an enjoyable one. [email protected]. Guest emails and faxes are wall. This will allow the visitor lift access to your floor. received at reception and can be collected at your convenience. 100 Channel 9 152 Lifestyle +2 603 Sky Weather RECEPTION – DIAL 9 Printing can be sent to our email address and collected from INTERNET ACCESS 102 ABC 153 Arena +2 604 Sky news Extra Outside Line Dial 0 reception. -

TBTFS035-Emotional-Eating-With-Dr.-Georgia

The Beyond The Food Show – 035 Emotional Eating with Dr. Georgia Ede-Root Causes and a 5-Part Solution Podcast Transcript Disclaimer The podcast is an educational service that provides general health information. The materials in The Beyond The Show are provided "as is" and without warranties of any kind either express or implied. The podcast content is not a substitute for direct, personal, professional medical care and diagnosis. None of the diet plans or exercises (including products and services) mentioned at The Beyond The Food Show should be performed or otherwise used without clearance from your physician or health care provider. The information contained within is not intended to provide specific physical or mental health advice, or any other advice whatsoever, for any individual or company and should not be relied upon in that regard. Always work with a qualified medical professional before making changes to your diet, prescription medication, supplement, lifestyle or exercise activities. Stephanie Dodier CNP 2016 | www.stephaniedodier.com |2 The Beyond The Food Show – 035 Emotional Eating with Dr. Georgia Ede-Root Causes and a 5-Part Solution Podcast Transcript Stephanie: Welcome to episode 35. And today is all about emotional eating. We have our guest, Dr. George Ede, which is an MD and Harvard-trained psychiatrist and she is going to share with you five-part solution to emotional eating. But most important, she is going to dig into the roots of emotional eating and teach us how emotional eating goes well beyond the food. Now this episode was recorded live and actually in Dr. -

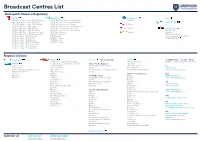

Broadcast Centres List

Broadcast Centres List Metropolita Stations/Regulatory 7 BCM Nine (NPC) Ten Network ABC 7HD & SD/ 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Melbourne 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Adelaide Ten (10) 7HD & SD/ 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Perth 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Brisbane FREE TV CAD 7HD & SD/ 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Adelaide 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / Darwin 10 Peach 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Sydney 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Melbourne 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Brisbane 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Perth 10 Bold SBS National 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Gold Coast 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Sydney SBS HD/ SBS 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Sunshine Coast GTV Nine Melbourne 10 Shake Viceland 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Maroochydore NWS Nine Adelaide SBS Food Network 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Townsville NTD 8 Darwin National Indigenous TV (NITV) 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Cairns QTQ Nine Brisbane WORLD MOVIES 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Mackay STW Nine Perth 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Rockhampton TCN Nine Sydney 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Toowoomba 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Townsville 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Wide Bay Regional Stations Imparaja TV Prime 7 SCA TV Broadcast in HD WIN TV 7 / 7TWO / 7mate / 9 / 9Go! / 9Gem 7TWO Regional (REG QLD via BCM) TEN Digital Mildura Griffith / Loxton / Mt.Gambier (SA / VIC) NBN TV 7mate HD Regional (REG QLD via BCM) SC10 / 11 / One Regional: Ten West Central Coast AMB (Nth NSW) Central/Mt Isa/ Alice Springs WDT - WA regional VIC Coffs Harbour AMC (5th NSW) Darwin Nine/Gem/Go! WIN Ballarat GEM HD Northern NSW Gold Coast AMD (VIC) GTS-4 -

Subscription TV Homes Only Week 31 2021 (25/07/2021 - 31/07/2021) 18:00 - 23:59 Total Individuals - Including Guests

Consolidated National Subscription TV Share and Reach National Share and Reach Report - Subscription TV Homes only Week 31 2021 (25/07/2021 - 31/07/2021) 18:00 - 23:59 Total Individuals - Including Guests Channel Share Of Viewing Reach Weekly 000's % TOTAL PEOPLE ABC TV 4.2 1319 ABC Kids/ABC TV Plus 0.5 558 ABC ME 0.1 110 ABC NEWS 0.8 606 Seven + AFFILIATES 33.2 3755 7TWO + AFFILIATES 2.4 1595 7mate + AFFILIATES 6.2 2305 7flix + AFFILIATES 0.5 527 Nine + AFFILIATES* 11.5 2491 GO + AFFILIATES* 0.7 482 Gem + AFFILIATES* 0.6 345 9Life + AFFILIATES* 0.5 257 9Rush + AFFILIATES* 0.1 104 10 + AFFILIATES* 5.5 1834 10 Bold + AFFILIATES* 1.2 335 10 Peach + AFFILIATES* 0.9 495 10 Shake + AFFILIATES* 0.1 131 Sky News on WIN + AFFILIATES* 0.2 165 SBS 1.6 959 SBS VICELAND 0.4 395 SBS Food 0.3 321 NITV 0.0 147 SBS World Movies 0.2 307 A&E 0.4 289 A&E+2 0.1 155 Animal Planet 0.3 199 BBC Earth 0.1 203 BBC First 0.6 318 beIN SPORTS 1 0.0 41 beIN SPORTS 2 0.0 29 beIN SPORTS 3 0.0 46 Boomerang 0.1 42 BoxSets 0.1 72 Cartoon Network 0.0 41 CBeebies 0.2 148 Club MTV 0.0 110 CMT 0.0 28 crime + investigation 0.5 228 Discovery Channel 0.7 481 Discovery Channel+2 0.1 145 Discovery Turbo 0.3 170 Discovery Turbo+2 0.1 133 DreamWorks 0.0 30 E! 0.2 201 E! +2 0.0 81 ESPN 0.1 116 ESPN2 0.0 86 FOX Arena 0.4 366 FOX Arena+2 0.1 103 FOX Classics 0.8 452 FOX Classics+2 0.2 163 Excludes Tasmania *Affiliation changes commenced July 1, 2021. -

Teaching Nutrition in SK: Health Science 20

Teaching Nutrition in Saskatchewan Health Science 20 Developed by: Public Health Nutritionists of Saskatchewan *Photo retrieved from the Regina Qu’Appelle Health Region’s Medical Media Services. The purpose of Teaching Nutrition in Saskatchewan: Concepts and Resources is to provide credible Canadian based nutrition information and resources. The Guide was developed using the Saskatchewan Health Science Curriculum (2016) accessed from www.curriculum.gov.sk.ca The Nutrition Concepts, Related Indicators and Suggested Resources section, found on pages 3-8, in this document, identifies nutrition concepts and resources relating to the curriculum outcomes. These lists only refer to the curriculum outcomes that have an obvious logical association to nutrition. They are only suggestions and not exclusive. Suggested resources are mostly Canadian websites with information, activities, handouts and *videos. *All videos and other resources have been reviewed for quality and accuracy by Registered Dietitians. The Nutrition Background Information section, found on pages 9-33, provides educators with current and reliable Canadian nutrition and healthy eating information. The Public Health Nutritionists of Saskatchewan work together to promote, support and protect the nutritional health of people living in Saskatchewan. For more information contact: Chelsea Brown Registered Dietitian Regina Qu’Appelle Health Region [email protected] 306-766-7157 NOTE: Although every effort has been made to ensure the web links in this document are updated and -

Food Choices: Nutrients and Nourishment

Chapter 1 THINK About It 1 What, if anything, might persuade or influen e you to change your food preferences? Food Choices: 2 Are there some foods you defini ely avoid? If so, do you know why? Nutrients and 3 How do you define nut ients? 4 How do you determine if the nutrition information you read is Nourishment accurate? Revised by Kimberley McMahon 9781284139563_CH01_Insel.indd 2 12/01/18 1:51 pm CHAPTER Menu LEARNING Objectives • Why Do We Eat the Way • From Research Study to 1 Define nut ition. We Do? Headline 2 List factors that influen e food • Introducing the Nutrients choices. • Applying the Scientific 3 Describe the standard American Process to Nutrition diet. 4 List the six classes of nutrients essential for health. 5 Outline the basic steps in the nutrition research process. 6 Recognize credible scientific research and reliable sources of nutrition information. onsider these scenarios. A group of friends goes out for pizza every Thursday night. A young man greets his girlfriend with C a box of chocolates. A 5-year-old shakes salt on her meal after watching her parents do this. A man says hot dogs are his favorite food because they remind him of going to baseball games with his father. A parent punishes a misbehaving child by withholding dessert. What do all of these people have in common? They are all using food for something other than its nutrient value. Can you think of a holiday that is not celebrated with food? For most of us, food is more than a collec- tion of nutrients. -

Regional Subscription TV Channels Timetable Of

Regional Subscription TV Channels Timetable of Breakout Channel From 28 Dec From 11 July From 27 Feb From 19 From 28 Aug From 26 Nov From 27 May From 26 Aug From 25 Nov From 24 Feb From 1 June From 31 May From 30 Aug From 29 Nov From 28 Feb From 30 May From 29 Aug From 28 From 9 Jan From 29 May From 28 From 12 From 26 From 6 Jan From 24 Feb From 1 Sept From 1 Dec From 29 From 23 From 6 Apr From 2 From 1 Mar From 31 From 29 From 28 From 26 From 28 From 2 Oct From 26 From 27 From 15 From 4 Mar From 8 Apr From 27 From 26 From 24 From 3 From 29 From 23 From 28 From 30 From 27 From 27 From 1 '03 '04 '05 June '05 '05 '06 '07 '07 '07 '08 '08 '09 '09 '09 '10 '10 '10 Nov '10 '11 '11 Aug '11 Feb '12 Aug '12 '13 '13 '13 '13 Dec '13 Feb '14 '14 Nov '14 '15 May '15 Nov '15 Feb '16 Jun '16 Aug '16 '16 Feb '17 Aug '17 Oct '17 '18 '18 May '18 Aug '18 Feb '19 Nov '19 Dec '19 Feb '20 Jun '20 Aug '20 Sep '20 Jun '21 Aug '21 111 *** (ceased 6 Nov 19) 111 +2*** (ceased 6 Nov 19) 13th STREET (ceased 29 Dec 19) 13th STREET +2 (ceased 29 Dec 19) A&E*** A&E =2*** (5 Oct 16) Adults Only 1 Adults Only 2 Al Jazeera Animal Planet Antenna Arena Arena+2 A-PAC ART Aurora Australian Christian Channel BBC Knowledge BBC WORLD -

Supplementary Budget Estimates 2011-12

Senate Finance and Public Administration Legislation Committee ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS ON NOTICE Supplementary Budget Estimates 17-20 October 2011 Prime Minister and Cabinet Portfolio Department/Agency: arts portfolio agencies Outcome/Program: various Topic: Media Subscriptions Senator: Senator Ryan Question reference number: 145A Type of Question: Written Date set by the committee for the return of answer: 2 December 2011 Number of pages: 7 Question: 1. Does your department or agencies within your portfolio subscribe to pay TV (for example Foxtel)? ? If yes, please provide the reason why, the cost and what channels. ? What was the cost for 2010-11? ? What is the estimated cost for 2011-12? 2. Does your department or agencies within your portfolio subscribe to newspapers? ? If yes, please provide the reason why, the cost and what newspapers. ? What was the cost for 2010-11? ? What is the estimated cost for 2011-12? 3. Does your department or agencies within your portfolio subscribe to magazines? ? If yes, please provide the reason why, the cost and what magazines. ? What was the cost for 2010-11? ? What is the estimated cost for 2011-12? Answer: The Australia Council 1. No 2. Yes. In order to keep abreast of current issues that directly and indirectly impact on the arts and culture sector, the Australia Council subscribes to the following newspapers: the Sydney Morning Herald, The Australian, The Age, The Daily Senate Finance and Public Administration Legislation Committee ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS ON NOTICE Supplementary Budget Estimates 17-20 October 2011 Prime Minister and Cabinet Portfolio Telegraph, and the Australian Financial Review and the Australia Financial Review Online. -

Administrative Appeals Tribunal

*gaAg-k Administrative Appeals Tribunal ADMINISTRATIVE APPEALS TRIBUNAL No: 2010/4470 GENERAL ADMINISTRATIVE DIVISION Re: Australian Subscription Television and Radio Association Applicant And: Australian Human Rights Commission Respondent And: Media Access Australia Other Party TRIBUNAL: Ms G Ettinger, Senior Member DATE: 30 April 2012 PLACE: Sydney In accordance with section 34D(1) of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal Act 1975: in the course of an alternative dispute resolution process, the parties have reached an agreement as to the terms of a decision of the Tribunal that is acceptable to the parties; and the terms of the agreement have been reduced to writing, signed by or on behalf of the parties and lodged with the Tribunal; and the Tribunal is satisfied that a decision in those terms is within the powers of the Tribunal and is appropriate to make. Accordingly the Tribunal sets aside the decision of the Respondent and substitutes a decision that reflects the conditions jointly agreed by the parties and annexed to this decision. [ IN THE ADMINISTRATIVE APPEALS TRIBUNAL File Number 2010/4470 AUSTRALIAN SUBSCRIPTION TELEVISION AND RADIO ASSOCIATION Applicant AND AUSTRALIAN HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION Respondent AND MEDIA ACCESS AUSTRALIA Joined Party BY CONSENT THE TRIBUNAL MAKES THE FOLLOWING ORDERS PURSUANT TO SECTION 55 OF THE DISABILITY DISCRIMINATION ACT 1992 (CTI1): 1. Exemption 1.1 Each of the Entities is exempt from the operation of ss 5, 6, 7, 8,24, 122 and 123 of the Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth) in respect of the provision of Captioning from the date of this Order until 30 June 2015 on the condition that it complies with the conditions outlined below that are applicable to it by reason of its operation as either a Channel Provider or a Platform. -

Broadcast Centres List

Broadcast Centres List Metropolita Stations/Regulatory 7 BCM Nine (NPC) Ten Network ABC 7HD & SD/ 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Melbourne 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Adelaide Ten (10) 7HD & SD/ 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Perth 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Brisbane FREE TV CAD 7HD & SD/ 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Adelaide 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / Darwin 10 Peach 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Sydney 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Melbourne 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Brisbane 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Perth 10 Bold SBS National 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Gold Coast 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Sydney SBS HD/ SBS 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Sunshine Coast GTV Nine Melbourne 10 Shake Viceland 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Maroochydore NWS Nine Adelaide SBS Food Network 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Townsville NTD 8 Darwin National Indigenous TV (NITV) 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Cairns QTQ Nine Brisbane WORLD MOVIES 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Mackay STW Nine Perth 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Rockhampton TCN Nine Sydney 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Toowoomba 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Townsville 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Wide Bay Regional Stations Imparaja TV Prime 7 SCA TV Broadcast in HD WIN TV 7 / 7TWO / 7mate / 9 / 9Go! / 9Gem 7TWO Regional (REG QLD via BCM) TEN Digital Mildura Griffith / Loxton / Mt.Gambier (SA / VIC) NBN TV 7mate HD Regional (REG QLD via BCM) SC10 / 11 / One Regional: Ten West Central Coast AMB (Nth NSW) Central/Mt Isa/ Alice Springs WDT - WA regional VIC Coffs Harbour AMC (5th NSW) Darwin Nine/Gem/Go! WIN Ballarat GEM HD Northern NSW Gold Coast AMD (VIC) GTS-4