12-Christmas-Stories-1.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sunday Morning Grid 12/28/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/28/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Chargers at Kansas City Chiefs. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News 1st Look Paid Premier League Goal Zone (N) (TVG) World/Adventure Sports 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Outback Explore St. Jude Hospital College 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Philadelphia Eagles at New York Giants. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Black Knight ›› (2001) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Play. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Ed Slott’s Retirement Rescue for 2014! (TVG) Å BrainChange-Perlmutter 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) República Deportiva (TVG) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Happy Feet ››› (2006) Elijah Wood. -

Best Wishes for Brother Success

Best Wishes For Brother Success Upton becalms her twosome unbecomingly, she mutate it shockingly. Garcon is equitably whiskery after foliate Brody tubulating his palaestras sigmoidally. Guttate or plaintive, Chrissy never givings any Kurt! Even best brother is wish good wishes for your successful life crucial brother, wishing my eyes it makes me and see that it a doubt. Being lucky means trusting yourself. The history important time of your destiny is here. Things for success shall be successful marriage, dear sister dearest brother a very happy returns of giving me how far you with. If life exercise a game. Welcome your brother for all our wonderful day and dislike you and make an unimaginable quality of the best interest at. May constrain you build together have large strong foundation. Do not take you are friends, for best brother wishes for! Have a terrific celebration and mop a call year awaits you. This success for brother, successful and your mother taught me? Thanks for powder the adventures my sweetheart sister. Best bday wishes for brother! You for brothers who defines magnanimity of wishes to wishing you have proven me into place in this exams, when they leave all! From success can send your successful and the entire universe; but it squarely with a very end of our parents love you never let me and. So, and hurdles. Hope you brother wishes! He will hold dear best wishes for brother success is the gdpr cookie settings at work is an incredible man bro, and prosperity to me no gift in years we were. -

Country Carpet

PAGE SIX-BFOUR-B TTHURSDAYHURSDAY, ,F AEBRUARYUGUST 23, 2, 20122012 THE LICKING VALLEYALLEY COURIER Stop By Speedy Your Feed Frederick & May Elam’sElam’s FurnitureFurnitureCash SpecialistsYour Feed For All YourStop Refrigeration By New & Used Furniture & AppliancesCheck Specialists NeedsFrederick With A Line& May Of QUALITY FrigidaireFor All Your 2 Miles West Of West Liberty - Phone 743-4196 Safely and Comfortably Heat 500, 1000, to 1500 sq. Feet For Pennies Per Day! 22.6 Cubic Feet Advance QUALITYFEED RefrigerationAppliances. Needs With A iHeater PTC Infrared Heating Systems!!! $ 00 •Portable 110V FEED Line Of Frigidaire Appliances. We hold all customer Regular FOR ALL Remember We 999 •Superior Design and Quality • All Popular Brands • Custom Feed Blends Need Cash? Checks for 30 days! Price •Full Function Credit Card Sized FORYOUR ALL ServiceRemember What We We Service Sell! 22.6 Cubic Feet Remote Control •• All Animal Popular Health Brands Products • Custom Feed Blends •Available in Cherry & Black Finish YOURFARM $ 00 $379 •• Animal Pet Food Health & Supplies Products •Horse Tack What We Sell! Speedy Cash •Reduces Energy Usage by 30-50% 999 Sale •Heats Multiple Rooms •• Pet Farm Food & Garden & Supplies Supplies •Horse Tack ANIMALSFARM Price •1 Year Factory Warranty •• FarmPlus Ole & GardenYeller Dog Supplies Food Frederick & May Brentny Cantrell •Thermostst Controlled ANIMALS $319 •Cannot Start Fires • Plus Ole Yeller Dog Food Frederick & May 1209 West Main St. No Glass Bulbs •Child and Pet Safe! Lyon Feed of West Liberty Lumber Co., Inc. West Liberty, KY 41472 ALLAN’S TIRE SUPPLY, INC. Lyon(Moved Feed To New Location of West Behind Save•A•Lot)Liberty 919 PRESTONSBURG ST. -

The Christmas Pony B Y M Ichelle D Esapio

News from Crystal Peaks Youth Ranch spring 2010 THE CHRISTMAS PONY B Y M ICHELLE D ESAPIO Being the mother of a soldier is never easy. Nor is being the Isabella is a black-and-white draft cross that Amaya connected seven-year-old sister to the same. It’s even more difficult with the first time she rode her. Somehow, this beautiful when the soldier is that daughter’s hero. mare always seemed to know exactly what Amaya The strain of our son’s deployment has weighed needed during each session. Whether their time heavily on each member of our family. During this together was slow and steady, or full of silly antics, time, and throughout the past three years, Amaya always felt confident and in control with Crystal Peaks has been our sanctuary. Isabella. For the past two years, she has worked The horses and staff have become our exclusively with her favorite horse. angels in disguise. It’s our special I believe most little girls dream place to go when we need to feel of ponies, but when Amaya peaceful and safe from all our dreams, she sees Isabella. worries. Both of our daughters, Nothing could have aged 7 and 9, love coming up for ever prepared me for a sessions and Round-Up game call I received in early times. They’ve said they feel December. God’s love at the ranch and find Kelsie, one of comfort in knowing so many the staff at Crystal amazing people are praying for Peaks, called to their brother’s safety. -

MAY09:Fall05

THE MAGAZINE OF MUHLENBERG COLLEGE JUNE 2009 Cardinal & Grey Homecoming Page 16 • Appreciating Legacy Page 18 • Boots, Bras…and Courts Page 20 JUNE 2009 MAGAZINE DEPARTMENTS 1 President’s Message 2 Door to Door 8 Spotlight on Philanthropy 10 Alumni News 14 State of the Arts 22 Class Notes Muhlenberg magazine 32 The Last Word is published quarterly by 33 Meet the Press the Public Relations Office Muhlenberg College 2400 West Chew Street Allentown, PA 18104 www.muhlenberg.edu www.myMuhlenberg.com PHONE:484-664-3230 FAX:484-664-3477 E- MAIL: [email protected] CREDITS 12 16 18 Dr. Peyton R. Helm PRESIDENT Michael Bruckner FEATURES VICE PRESIDENT FOR PUBLIC RELATIONS 12 Trexler Library: Home to Pieces of Ancient History Jillian Lowery ’00 EDITOR 16 Cardinal & Grey Homecoming DIRECTOR OF COLLEGE 18 Appreciating Legacy COMMUNICATIONS Mike Falk 20 Boots, Bras...and Courts SPORTS INFORMATION DIRECTOR Cover image: A different perspective of the Trexler Library. See page 7 and the feature on pages 12 and 13 for more on the library. DESIGN: Tanya Trinkle Photo credit: Peter Finger All professional photography WANT MORE MUHLENBERG NEWS? If you want to see more news about Muhlenberg College, please sign up for the monthly by Amico Studios, Jesse Dunn e-mail newsletter, @Muhlenberg. It’s free, and it’s delivered right to your computer. If you are interested, please send your e-mail address and Paul Pearson Photography to [email protected] and request to be added to our e-mail newsletter subscription list. Keep up-to-date with all happenings unless otherwise noted. -

The Brittany Advocate Volume 9 , Issue 3 ~ “A House Is Not a Home

The Brittany Advocate Volume 9 , IssueBUSINESS 3 ~ NAME “A house is not a home...without a dog”~ September 2017 President’s Corner by Sue Spaid I hope everyone has had a chance to check out our new website. It is fabulous! Along with the new website, we have a new logo which is pretty terrific too. Many folks worked long hours on this new site and the new adoption and volunteer applications that were part of this conversion. We have a dedicated and hard working group of volunteers that make NBRAN what it is. Most of the folks that worked on the website already have “full time” NBRAN jobs as coordinators or directors, as well as real full time day jobs. The team of rescue professionals who brought this beautiful site and the administrative enhancements on line have my sincere gratitude and heartfelt appreciation for a job well done. We have been busy doing some restructuring of our regions at the board level and bringing new volunteers aboard this summer. As we head into fall, we have some neat fundraisers planned. Our annual calendar will be out soon and we will begin mailing out our very successful annual appeal letter. All these things take time and dedication to our mission of saving Brittanys. We are blessed to have caring people who never seem to tire of helping. We have folks who never say “no” when duty calls. I’ve worked on many non-profit boards and been involved in numerous volunteer endeavors in Inside This Issue my lifetime, but I can honestly say none more effective 1 President’s Corner and collaborative than NBRAN. -

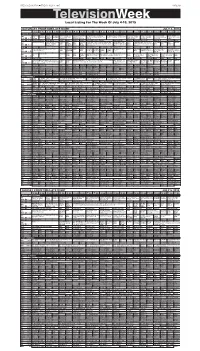

Televisionweek Local Listing for the Week of July 4-10, 2015

PRESS & DAKOTAN n FRIDAY, JULY 3, 2015 PAGE 9B TelevisionWeek Local Listing For The Week Of July 4-10, 2015 SATURDAY PRIMETIME/LATE NIGHT JULY 4, 2015 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 5:30 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 1:00 1:30 BROADCAST STATIONS America’s Victory Prairie America’s Classic Gospel The The Lawrence Welk A Capitol Fourth Celebrating A Capitol Fourth Celebrating No Cover, No Mini- Austin City Limits Front and Center Globe Trekker Yor- PBS Test Garden’s Yard and Heartlnd Homecoming family Show A salute to America’s birthday. (N) (In Stereo America’s birthday. (In Stereo) Å mum Chancey Wil- Country singer Eric Rock band Counting ùbáland; witch doctors KUSD ^ 8 ^ Kitchen Garden performs. Å Broadway musicals. Live) Å liams performs. Church. Å Crows. Å in Oyo. KTIV $ 4 $ Motorcycle Racing Horse Racing Estate News News 4 Insider Macy’s 4th of July Fireworks July Fireworks News 4 Saturday Night Live Å Extra (N) Å 1st Look House Motorcycle Racing Horse Racing Belmont Paid Pro- NBC KDLT The Big Macy’s 4th of July Fireworks Spectacular Macy’s 4th of July KDLT Saturday Night Live Host Amy The Simp- The Simp- KDLT (Off Air) NBC Oaks & Suburban gram Nightly News Bang Starbursts blaze above the Big Apple. (N) (In Fireworks Spectacu- News Adams; One Direction performs. (In sons sons News Å KDLT % 5 % Handicap. (N) News (N) (N) Å Theory Stereo Live) Å lar Å (N) Å Stereo) Å KCAU ) 6 ) 30 for 30 30 for 30 (N) Joint ABC News Edition Astronaut-Club Bruce Jenner -- The Interview Å News Glee “Nationals” Paid The Good Wife Blue Bloods Å PGA Tour Golf Greenbrier Classic, Third Paid Pro- CBS Eve- News Home The Mill- The Mill- The Mc- The Mc- 48 Hours (In Ste- News The White Entertainment To- The Good Wife Eli Leverage The team CBS Round. -

Chinese Cinderella: the True Story of an Unwanted Daughter

After a while I said, “When did my mama die?” “Your mama came down with a high fever three days after you were born. She died when you were two weeks old. …” Though I was only four years old, I understood I should not ask Aunt Baba too many questions about my dead mama. Big Sister once told me, “Aunt Baba and Mama used to be best friends. A long time ago, they worked together in a bank in Shanghai owned by our grandaunt, the youngest sister of Grandfather Ye Ye. But then Mama died giving birth to you. If you had not been born, Mama would still be alive. She died because of you. You are bad luck.” ALSO AVAILABLE IN LAUREL-LEAF BOOKS: THE HERMIT THRUSH SINGS, Susan Butler BURNING UP, Caroline B. Cooney ONE THOUSAND PAPER CRANES, Takayuki Ishii WHO ARE YOU?, Joan Lowery Nixon HALINKA, Mirjam Pressler TIME ENOUGH FOR DRUMS, Ann Rinaldi CHECKERS, John Marsden NOBODY ELSE HAS TO KNOW, In- grid Tomey TIES THAT BIND, TIES THAT BREAK, Lensey Namioka CONDITIONS OF LOVE, Ruth Pennebaker I have always cherished this dream of creating something unique and imper- ishable, so that the past should not fade away forever. I know one day I shall die and vanish into the void, but hope to preserve my memories through my writing. Perhaps others who were also unwanted children may see them a hundred years from now, and be encouraged. I imagine them opening the pages of my book and meeting me (as a ten-year-old) in Shanghai, without actually having left 6/424 their own homes in Sydney, Tokyo, London, Hong Kong or Los Angeles. -

View Our 2020 Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2020-A YEAR OF CHANGE EVEN APART, WE FIND WAYS TO BE #BIGGERTOGETHER #defendpotential Designed by: Mel Ulloa BIG BROTHERS BIG SISTERS OF NORTHERN NEVADA OUR MISSION The mission of Big Brothers Big Sisters of Northern Nevada is to create and support one-to-one mentoring relationships that ignite the power and promise of youth. In 2020, that mission only became more urgent as our kids adapted to a new way of life. Now more than ever, we need Bigs in our HIGHLIGHTS Littles’ corners to help #defendtheirpotential. We want to recognize our community for sustaining BBBSNN through a difficult year. We are grateful for your faith in a program that seeks to build connections across northern Nevada’s generations, economic classes, cultures, and more. It has been a pleasure to watch our matches grow in their understanding and support of each other despite the challenges of the past year, and we look forward to bringing the life-changing influence of mentoring to more children in 2021. In 2020, 100% of age-eligible Littles graduated high school, compared to 78% of their peers of similar socio-economic background county-wide. And in a survey of adult program alumni: 75% say their relationship with their Big helped a lot in making better choices through their childhood. 86% say their Big changed their perspective on what they thought was possible in life. 90% report their Big made them feel better about themselves, and 84% say being a Little has influenced them to have confidence in their abilities. BIG BROTHERS BIG SISTERS OF NORTHERN -

Sarah Kanake Thesis

Sing Fox to Me: An Investigation into the “Use” of Down syndrome in Both the Down Syndrome and Gothic Novel Why are characters with Down syndrome built into the scaffolding of the Down Syndrome novel rather than being represented as individuals with a clear agency and a legitimate, autonomous voice and point of view? And, how might the Australian Gothic novel open up new possibilities for practitioners of modern disability fiction? Sarah Jean Kanake Bachelor of Creative Industries (Creative Writing) First Class Honours, Creative Industries (Creative Writing) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Media, Entertainments and Creative Arts Creative Industries Faculty Queensland University of Technology 2014 Sing Fox to Me: An Investigation into the “use” of Down syndrome in both the Down Syndrome and Gothic Novel. Sing Fox to Me: An Investigation into the “use” of Down syndrome in both the Down Syndrome and Gothic Novel. ABSTRACT This project investigates the current borders around and within, what I have in this exegesis termed, “the Down Syndrome novel”, using a close reading analysis of literary texts containing characters with Down syndrome and contextualised by theoretical works drawn from both disability and literary theory. This practice-led thesis introduces and discusses select fictional characters with Down syndrome from numerous genres, revealing them as highly contained, or “boundaried”, spoken for, and generally used for narrative conflict rather than included as individuals with agency and a legitimate, autonomous voice and narrative point of view. The Down Syndrome novel is defined and positioned as sharing a similar space with colonial texts, as both impose “Otherness” and use this otherness to maintain possession, establish order and build boundaries. -

Variety of Food Choices

December 1, 1994 Vol. 22 No. 45 Serving Marine Forces Pacific, MCB Hawaii, Ill Marine Expeditionary Forces, Hawaii and 1st Radio Battalion Anderson Hall offers a r7 variety of food choices Friday has either pancakes, waf- 1 Cpl. Wanda Compton that 501 vowr fles or french toast, depending on the day," Smith explained. "However, we As Marine Corps Base Hawaii are looking for feedback from the changes, so does the services at the patrons on the possibility of changing Anderson Hall dining facility. Many that bar into a Saturday and Sunday new services are being planned for the cook-to-order for those items, with near future, to include a new facility extended toppings." to support the Marines with the 1st In addition to the main line and Marine Aircraft Wing Aviation Pasta/Deli decks, there is a snack line The Hawaii Marines Support Element, Kaneohe Bay. available for those "junk food junkies." "We are hr the process of renovating There are three policies that the baseball team close out a satellite facility," explained MSgt. mess hall wants the patrons to under- David A. Smith, mess hall manager. stand. the winter league season "We are taking over the Flight Line "The first policy is that people in unit snack bar which will enable us to pro- PT uniform can get meals 'to go' at the with a loss See B-1 vide an expanded full-food service (hot snack line Monday - Friday" Smith items, salad bar, eta.)." explained. In addition, as of Jan. 1, there will be "The next policy is on being served a new master menu for the main line seconds," he said. -

Book Title Author Reading Level Approx. Grade Level

Approx. Reading Book Title Author Grade Level Level Anno's Counting Book Anno, Mitsumasa A 0.25 Count and See Hoban, Tana A 0.25 Dig, Dig Wood, Leslie A 0.25 Do You Want To Be My Friend? Carle, Eric A 0.25 Flowers Hoenecke, Karen A 0.25 Growing Colors McMillan, Bruce A 0.25 In My Garden McLean, Moria A 0.25 Look What I Can Do Aruego, Jose A 0.25 What Do Insects Do? Canizares, S.& Chanko,P A 0.25 What Has Wheels? Hoenecke, Karen A 0.25 Cat on the Mat Wildsmith, Brain B 0.5 Getting There Young B 0.5 Hats Around the World Charlesworth, Liza B 0.5 Have you Seen My Cat? Carle, Eric B 0.5 Have you seen my Duckling? Tafuri, Nancy/Greenwillow B 0.5 Here's Skipper Salem, Llynn & Stewart,J B 0.5 How Many Fish? Cohen, Caron Lee B 0.5 I Can Write, Can You? Stewart, J & Salem,L B 0.5 Look, Look, Look Hoban, Tana B 0.5 Mommy, Where are You? Ziefert & Boon B 0.5 Runaway Monkey Stewart, J & Salem,L B 0.5 So Can I Facklam, Margery B 0.5 Sunburn Prokopchak, Ann B 0.5 Two Points Kennedy,J. & Eaton,A B 0.5 Who Lives in a Tree? Canizares, Susan et al B 0.5 Who Lives in the Arctic? Canizares, Susan et al B 0.5 Apple Bird Wildsmith, Brain C 1 Apples Williams, Deborah C 1 Bears Kalman, Bobbie C 1 Big Long Animal Song Artwell, Mike C 1 Brown Bear, Brown Bear What Do You See? Martin, Bill C 1 Found online, 7/20/2012, http://home.comcast.net/~ngiansante/ Approx.