1 Relfections on the Demography of the Jewish

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VISTA ROMA ROMA La Cupola Di San Pietro, in Lontananza, Troneggia Sul Tevere Illuminato

VISTA ROMA ROMA La cupola di San Pietro, in lontananza, troneggia sul Tevere illuminato. Sulle sponde fermento e bancarelle: da giugno ad agosto la manifestazione “Lungo il Tevere...Roma” anima l’estate capitolina. Fascino immortale Cambiamenti e trasformazioni hanno accompagnato alcuni quartieri di Roma. Monti, Trastevere, Pigneto e Centocelle, in tempi e modi diversi, portano avanti la loro rinascita: sociale, gastronomica e culturale DI VIOLA PARENTELLI 40 _ LUGLIO 2019 ITALOTRENO.IT ITALOTRENO.IT LUGLIO 2019 _ 41 VISTA ROMA A destra, un pittoresco scorcio di Monti e sullo sfondo la Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore. Fafiuché, vineria nascosta tra i vicoli del rione, è una tappa obbligata per sorseggiare un calice di vino. isomogenea, caotica, imperfetta. Impo- “zona abitata sotto la città” ne richiama nente nella sua maestosità storica, fami- la struttura: che si scenda dalla Salita liare nei dettagli visibili solo agli sguardi dei Borgia o da Via dei Serpenti, tutte le più attenti. Con Roma ci vuole pazienza, scale portano qui. Tolti gli abiti di luogo e ci vuole empatia. Roma accoglie, ma malfamato che era in origine, da qualche solo chi sa leggerne le infinite anime po- decennio è una delle mete più apprezzate trà sentirsi davvero a casa. Per ammirar- per il suo fascino un po’ rétro. Dopo una ne la bellezza, le terrazze sono luoghi pri- visita al mercatino vintage a pochi passi vilegiati. Il Roof 7 Terrace di Le Méridien dall’uscita della metro B, camminare su Visconti, a Prati, gode di questa fortuna. quegli infiniti sanpietrini diventa quasi D Un salotto con vista dove appagare il pa- piacevole. -

The Spirit of Rome, by Vernon Lee 1

The Spirit of Rome, by Vernon Lee 1 The Spirit of Rome, by Vernon Lee The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Spirit of Rome, by Vernon Lee This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: The Spirit of Rome Author: Vernon Lee Release Date: January 22, 2009 [EBook #27873] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 The Spirit of Rome, by Vernon Lee 2 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE SPIRIT OF ROME *** Produced by Delphine Lettau & the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries. THE SPIRIT OF ROME BY VERNON LEE. CONTENTS. Explanatory and Apologetic I. First Return to Rome II. A Pontifical Mass at the Sixtine Chapel III. Second Return to Rome IV. Ara Coeli V. Villa Cæsia VI. The Pantheon VII. By the Cemetery SPRING 1895. I. Villa Livia II. Colonna Gallery III. San Saba IV. S. Paolo Fuori V. Pineta Torlonia SPRING 1897. I. Return at Midnight II. Villa Madama III. From Valmontone to Olevano IV. From Olevano to Subiaco V. Acqua Marcia VI. The Sacra Speco VII. The Valley of the Anio VIII. Vicovaro IX. Tor Pignattara X. Villa Adriana XI. S. Lorenzo Fuori XII. On the Alban Hills XIII. Maundy Thursday XIV. Good Friday XV. -

Itinerary (As of April 9, 2013)

The Undiscovered Coast of Italy Puglia and Basilicata: A Travel Adventure for Alumni & Friends of Duquesne University May 30 – June 9, 2013 Itinerary (As of April 9, 2013) Thursday, May30 Depart USA for Rome, Italy!! Travel from your home city overnight to arrive the next morning in Rome, the Eternal City. Friday, May 31 Rome After an early morning arrival in Rome, our flights arriving at Leonardo DaVinci (“Fiumicino”) airport will be met just outside Baggage Claim by our trip leader, Dr. Jean Anne Hattler, and by Michael Wright, Director of Duquesne University’s Italian Campus program. We’ll be transferred via motorcoach to our hotel for the next two nights, Hotel 21 (www.twentyonerome.com), located near the Piazza del Popolo in central Rome, approximately mid-way between the Vatican Museums and the Spanish Steps. We’ll leave our bags at the hotel and take a special topical walking tour through Piazza del Popolo, the Via del Corso, and the Spanish Steps while we wait for the rooms to be ready for check-in. This evening, we’ll enjoy a welcome dinner at Ristorante Gusto. Independent Lunch. Overnight in Rome at Hotel 21. (D) Saturday, June 1 Rome This morning you’ll have the opportunity to explore a special moment in Roman history: the early Christian era from when Christianity was either illegal and underground to when it emerged in the early 4th century as the official religion of the Roman Empire. We’ll start at the Catacombs of St. Priscilla, known as the “Queen of the Catacombs” for the large number of martyrs who are buried in this complex, with Latinist and Church historian, Gregory DiPippo. -

Rome in a Pocket

FEBA ANNUAL CONVENTION 2019 TOWARDS THE NEXT DECADE. TOGHETHER ROME IN A POCKET 15-18 MAY 2019 1 When in Rome, do as Romans do The best way to visit, understand and admire the eternal city is certainly with…a pair of good shoes. Whoever crosses the old consular road of the ancient Appia, known as “Queen Viarum” notices immediately tourists in single file, walking the edge of the street on the little sidewalk. Along the way we reach the Catacombs of San Callisto and San Sebastiano, where, still today, the stones and the intricate underground tunnels, (explored for only 20 km), retain a charm of mystery and spirituality. We are in the heart of Rome, yet we find ourselves immersed in a vast archaeological park hidden by cultivated fields while, in the distance, we can see long lines of buildings. A few meters from the entrance of the Catacombs of S. Sebastiano, an almost anonymous iron gate leads to the Via Ardeatina where, a few minutes away, we find the mausoleum of the “Fosse Ardeatine”. It is the place dedicated to the 335 victims killed by the Nazi-fascist regime in March 1944, as an act of retaliation for the attack on Via Rasella by partisan groups that caused the death of German soldiers. 2 COLOSSEUM Tourists know the most symbolic In 523 A.D., the Colosseum ends place to visit and cannot fail to its active existence and begins see the Flavian amphitheater, a long period of decadence known as Colosseum due to the and abandonment to become a giant statue of Nero that stood quarry of building materials. -

Title: from Iconoclasm to Museum: Mussolini's Villa in Rome As A

Title: From Iconoclasm to Museum: Mussolini’s Villa in Rome as a Dictatorial Heritage Site Author: Flaminia Bartolini How to cite this article: Bartolini, Flaminia. 2018. “From Iconoclasm to Museum: Mussolini’s Villa in Rome as a Dictatorial Heritage Site.” Martor 23: 163-173. Published by: Editura MARTOR (MARTOR Publishing House), Muzeul Ţăranului Român (The Museum of the Romanian Peasant) URL: http://martor.muzeultaranuluiroman.ro/archive/martor-23-2018/ Martor (The Museum of the Romanian Peasant Anthropology Journal) is a peer-reviewed academic journal established in 1996, with a focus on cultural and visual anthropology, ethnology, museum studies and the dialogue among these disciplines. Martor Journal is published by the Museum of the Romanian Peasant. Interdisciplinary and international in scope, it provides a rich content at the highest academic and editorial standards for academic and non-academic readership. Any use aside from these purposes and without mentioning the source of the article(s) is prohibited and will be considered an infringement of copyright. Martor (Revue d’Anthropologie du Musée du Paysan Roumain) est un journal académique en système peer-review fondé en 1996, qui se concentre sur l’anthropologie visuelle et culturelle, l’ethnologie, la muséologie et sur le dialogue entre ces disciplines. La revue Martor est publiée par le Musée du Paysan Roumain. Son aspiration est de généraliser l’accès vers un riche contenu au plus haut niveau du point de vue académique et éditorial pour des objectifs scientifiques, éducatifs et informationnels. Toute utilisation au-delà de ces buts et sans mentionner la source des articles est interdite et sera considérée une violation des droits de l’auteur. -

Solo Alfabetiere Impaginato

ROMA A-Z alfabeti della città SABATO 06 OTTOBRE E COME ECLETTISMO Musei di Villa Torlonia Intorno all’Eclettismo laboratorio e visita didattica per adulti Ore 16:00 A cura di A.L.I.C.E., 06/99701857-cellulare 335/5822433 oppure [email protected] E COME EGITTO Museo di Scultura Antica Giovanni Barracco La Collezione Egizia visita didattica e laboratorio di scrittura geroglifica per famiglie Ore 11.00 A cura di Arx, 337/373414 - 338/3424820 E COME ECLETTISMO Il quartiere Coppedè visita didattica Ore 10:30 A cura di Bell’Italia 88, 06/39728186 oppure [email protected] DOMENICA 07 OTTOBRE E COME ECLETTISMO Musei di Villa Torlonia Intorno all’Eclettismo laboratorio e visita didattica per adulti Ore 10:30 A cura di A.L.I.C.E., 06/99701857-cellulare 335/5822433 oppure [email protected] E COME EGITTO Museo di Scultura Antica Giovanni Barracco La Collezione Egizia visita didattica e laboratorio di scrittura geroglifica per famiglie Ore 10:00 A cura di Arx, 337/373414 - 338/3424820 SABATO 27 OTTOBRE C COME COSTANTINO Musei Capitolini I ritratti imperiali visita didattica Ore 16:30 A cura di Pierrecicodess, 06/39967800 C COME COSTANTINO Museo della Civiltà Romana L’età di Costantino attraverso le opere del Museo della Civiltà Romana visita didattica Ore 10:00 A cura di Arx, 337/373414 - 338/3424820 C COME COSTANTINO I luoghi della battaglia: Ponte Milvio - la vittoria visita didattica con passeggiata fino al nuovo Ponte della Musica Ore 10:30 A cura di Bell’Italia 88, 06/39728186 oppure [email protected] C COME COSTANTINO Eurisace, Elena, Costantino, San Giovanni: pagani e cristiani lungo le Mura Aureliane visita didattica al tratto di Mura tra Porta Asinaria e la Chiesa di S. -

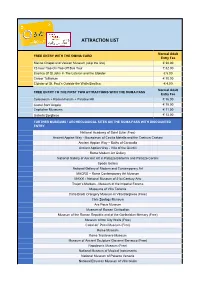

Attraction List

ATTRACTION LIST Normal Adult FREE ENTRY WITH THE OMNIA CARD Entry Fee Sistine Chapel and Vatican Museum (skip the line) € 30.00 72-hour Hop-On Hop-Off Bus Tour € 32.00 Basilica Of St.John In The Lateran and the Cloister € 5.00 Carcer Tullianum € 10.00 Cloister of St. Paul’s Outside the Walls Basilica € 4.00 Normal Adult FREE ENTRY TO THE FIRST TWO ATTRACTIONS WITH THE ROMA PASS Entry Fee Colosseum + Roman Forum + Palatine Hill € 16.00 Castel Sant’Angelo € 15.00 Capitoline Museums € 11.50 Galleria Borghese € 13.00 FURTHER MUSEUMS / ARCHEOLOGICAL SITES ON THE ROMA PASS WITH DISCOUNTED ENTRY National Academy of Saint Luke (Free) Ancient Appian Way - Mausoleum of Cecilia Metella and the Castrum Caetani Ancient Appian Way – Baths of Caracalla Ancient Appian Way - Villa of the Quintili Rome Modern Art Gallery National Gallery of Ancient Art in Palazzo Barberini and Palazzo Corsini Spada Gallery National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art MACRO – Rome Contemporary Art Museum MAXXI - National Museum of 21st Century Arts Trajan’s Markets - Museum of the Imperial Forums Museums of Villa Torlonia Carlo Bilotti Orangery Museum in Villa Borghese (Free) Civic Zoology Museum Ara Pacis Museum Museum of Roman Civilization Museum of the Roman Republic and of the Garibaldian Memory (Free) Museum of the City Walls (Free) Casal de’ Pazzi Museum (Free) Rome Museum Rome Trastevere Museum Museum of Ancient Sculpture Giovanni Barracco (Free) Napoleonic Museum (Free) National Museum of Musical Instruments National Museum of Palazzo Venezia National Etruscan -

Lazio (Latium) Is a Region of Traditions, Culture and Flavours

Lazio (Latium) is a Region of traditions, culture and flavours. A land that knows how to delight the visitor at any time of the year, thanks to its kaleidoscope of landscape and stunning scenery, ranging from the sea to the mountains, united by a common de- nominator: beauty. The beauty you will find, beside the Eternal City, in Tuscia, Sabina, Aniene and Tiber Valley and along the Ro- man Hills, without forgetting the Prenestine and Lepini mountains, the Ciociaria and the Riviera of Ulysses and Aeneas coasts with the Pontine islands. The main City is, obvi- ously Rome, the Eternal City, with its 28 hundred years, so reach of history and cul- ture, but, before the rise of Rome as a mili- tary and cultural power, the Region was already called Latium by its inhabitants. Starting from the north west there are three distinct mountain ranges, the Volsini, the Cimini and the Sabatini, whose volcanic origin can be evinced by the presence of large lakes, like Bolsena, Vico and Bracciano lake, and, the Alban Hills, with the lakes of Albano and Nemi, sharing the same volcanic origins. A treasure chest concealing a profu- sion of art and culture, genuine local prod- ucts, delicious foods and wine and countless marvels. Rome the Eternal City, erected upon seven hills on April 21st 753 BC (the date is sym- bolic) according to the myth by Romulus (story of Romulus and Remus, twins who were suckled by a she-wolf as infants in the 8th century BC. ) After the legendary foundation by Romulus,[23] Rome was ruled for a period of 244 years by a monarchical system, ini- tially with sovereigns of Latin and Sabine origin, later by Etruscan kings. -

Villa Torlonia

VILLA TORLONIA UNA STUPENDA VILLA NEOCLASSICA, RINATA A NUOVA VITA NEGLI ULTIMI ANNI INFORMAZIONI PRATICHE La villa è aperta, come tutte le ville romane, dall'alba al tramonto, i musei della villa sono aperti tutti i giorni tranne il lunedì dalle ore 9 alle ore 19. Il costo del biglietto di ingresso è di € 6,50, ridotto di € 4,50. Il biglietto è gratuito per i ragazzi al di sotto dei 18 anni e per le persone maggiori di 65. La prenotazione è obbligatoria per i gruppi (12-30 persone), costo della prenotazione è di € 25. La villa si può raggiungere con la metro B scendendo alla fermata Policlinico e procedendo per 600 metri su viale Regina Margherita, piazza Galeno, via Bartolomeo Eustachio, quindi entrando nella villa dall'entrata laterale di via Lazzaro Spallanzani. Oppure dalla stazione Termini con il filobus 90 o il bus 36. PREMESSA Villa Torlonia si trova lungo la via Nomentana n. 70, nel quartiere Nomentano che fa parte del III Municipio del Comune di Roma. La villa fu voluta dal banchiere Giovanni Torlonia (1756-1829) che acquistò nel 1797 una tenuta agricola dai Colonna. Il complesso neoclassico fu iniziato da Giuseppe Valadier1 nel 1802. Alla morte di Giovanni il figlio Alessandro (1800 -1880, questi, tra l’altro, realizzò il prosciugamento del lago del Fucino in Abruzzo) continuò i lavori dandone incarico a Giovanni Battista Caretti2 dal 1832. Alessandro volle i due obelischi che si trovano davanti e dietro il Casino Nobile, in onore dei genitori. Ad Alessandro subentrò il nipote Giovanni (Alessandro ebbe due figlie, una andò in sposa ad un Borghese che prese anche il nome Torlonia per continuare la casata) che fece trasformare la capanna svizzera in Casina delle Civette. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Must Do Specials St. Peter's Church Vatican Museums Colonna Palace and Doria Pamphilj 14- 24 | | 42 - 49 | Ancient Rome Tour | City Tour | Rome by Villa Medici | Cornelia Costanza's Secret Night Tour | Catacombs Tour | Apartments | The Catacombs of San Angels and Demons | Underground Rome | Pancrazio | Boat Sightseeing to Ancient The Borghese Gallery | Heart of Rome Ostia | Secret Rome | Oratorio del Gonfalone and Villa Farnesina Special Vatican Tours Experiences Vatican Under the Stars Vatican Relax Art Evening Food and Wine Tasting | 25 - 35 | | 50 - 58 and Breakfast | Vatican Gardens | Morning Food Tour | Pizza Baking and Early Morning Vatican Tour | Vatican Secret Pasta Cooking | Jogging Tour | Cooking Experience with an Italian Family | Rooms | The Niccolina Chapel | Vatican Cooking Experience with an Italian Museums + Necropolis of the Via Triumphalis Family, plus your Tour Guide | Pizza and | Exclusive Vatican | Semi Exclusive Vatican Gelato Class | Veggie Food Tour in Rione Monti Outside Rome Rome on Wheels 36 - 41 Castelli Romani | Ancient Ostia | Tivoli | 59 - 64 Vintage Vespa Tour | Rome Golf Cart Tour Etruscan Highlights of Cerveteri | Etruscan | Rome By Vintage Fiat 500 | Rome Bike Highlights of Tarquinia Tour | Rome Segway Tour Thematic Tours Group Activities In the Footsteps of Michelangelo Rome in 65 - 83 | 94 - 98 Aperitif at Villa Farnesina | Group The Movies | In the Footsteps of Caravaggio | Scavenger Hunt | Ancient Aperitif at the In theFootsteps of Bernini | In the Footsteps Houses on the Celio Hill | Aperitif at Villa of St. Paul | In the Footsteps of J. Caesar | Medici Roman Christian Mosaics | Jubilee Basilica | Industrial innovation and archeology | XX Century Rome | Contemporary Art in Rome | Palazzo Spada and Villa Farnesina | The EUR Quarter | The Art of Local Craftmanship | A Semi-Private Tours Progressive Dining Experience | dive into Roman History | The Great Beauty 99 - 103 | Jewish Rome | Romance in Rome Colosseum and Ancient Rome | Vatican Museums and St. -

THE VILLAS Roma Ti Aspetta PIEGHEVOLI Definitiviinglese4antmodif Layout125/10/1019.29Pagina8 and History Greenery Oases of Discovering

PIEGHEVOLI DEFINITIVI INGLESE 4 ant MODIF_Layout 1 25/10/10 19.29 Pagina 7 Call number Marvellous villas (note that a villa is a resi- Addresses dence immersed in its own grounds, so that 060608 1 Pincio. Metro: line A, Flaminio stop. or visit the villa may refer to the house or to the 2 Casa del Cinema. Largo Marcello Mastroianni, 1. www.turismoroma.it Tel. +39 06 423601; www.casadelcinema.it. Metro: line grounds), rich in history and fascination: a A, Flaminio stop and then any bus going into Villa For tourist information, Borghese, or the Spagna or Barberini stop and bus 116. cultural events and entertainment offered in Rome refreshing walk amid the greenery of nature 3 Villa Borghese. Entrances at Via Aldrovandi, Via [Roma tiaspetta and the whiteness of the splendid marble Raimondi, Via Pinciana, Piazzale San Paolo del Brasile, LIST OF T.I.P. (Tourism Information Points) Piazzale Flaminio e Piazzale Cervantes. Open from dawn work. A complex union of art, architecture to dusk. Buses: 116 (inside the Villa); 88, 95, 490, 495 and • G.B. Pastine Ciampino 49 (which run also inside the Villa); 910, 52, 53, 628, 926, International Arrivals – Baggage Collection Area (9.00 - 18.30) and nature, that of the “green city”, which in 223 and 217. Trams: 19, 3 and 2. Metro: line A, Flaminio • Fiumicino or Spagna stop. Railway station: Rome-Viterbo, Piazzale International Airport "Leonardo Da Vinci"- Arrivals Rome goes hand in hand with the “city of Flaminio stop. International - Terminal T - 3 (9.00 - 18.30) 4 Globe Theatre. -

Rome-English

STIG ALBECK TRAVEL TO ROME DOWNLOAD FREE TRAVEL GUIDES AT BOOKBOON.COM NO REGISTRATION NEEDED Download free books at BookBooN.com 2 Rome © 2010 Stig Albeck & Ventus Publishing ApS All rights and copyright relating to the content of this book are the property of Ventus Publishing ApS, and/or its suppliers. Content from ths book, may not be reproduced in any shape or form without prior written permission from Ventus Publishing ApS. Quoting this book is allowed when clear references are made, in relation to reviews are allowed. ISBN 978-87-7061-439-9 2nd edition Pictures and illustrations in this book are reproduced according to agreement with the following copyright owners Stig Albeck & Rome. The stated prices and opening hours are indicative and may have be subject to change after this book was published. Download free books at BookBooN.com 3 Rome CHAPTER Download free books at BookBooN.com 4 Rome Travelling to Rome Travelling to Rome www.romaturismo.com www.comune.roma.it www.enit.it Rome is the Eternal City, to which tourists will come back again and again to make new discoveries. As the centre of the Roman Empire, Rome's history is second to none, and everywhere around the 7 hills of Rome this becomes apparent. All roads lead to Rome; and just as well, because going there once is not enough. The Romans, the climate, the history and the gastronomy make for a lovely southern atmosphere to be remembered forever. The buildings of antique Rome, the Colosseum and Forum Romanum being the most well known, are unique, but later periods have also left behind some worthwhile attractions.