TRANSCRIPT of INTERVIEW with EMMET LAVERY by Mae Mallory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mixed Folios

mixed folios 447 The Anthology Series – 581 Folk 489 Piano Chord Gold Editions 473 40 Sheet Music Songbooks 757 Ashley Publications Bestsellers 514 Piano Play-Along Series 510 Audition Song Series 444 Freddie the Frog 660 Pop/Rock 540 Beginning Piano Series 544 Gold Series 501 Pro Vocal® Series 448 The Best Ever Series 474 Grammy Awards 490 Reader’s Digest Piano 756 Big Band/Swing Songbooks 446 Recorder Fun! 453 The Big Books of Music 475 Great Songs Series 698 Rhythm & Blues/Soul 526 Blues 445 Halloween 491 Rock Band Camp 528 Blues Play-Along 446 Harmonica Fun! 701 Sacred, Christian & 385 Broadway Mixed Folios 547 I Can Play That! Inspirational 380 Broadway Vocal 586 International/ 534 Schirmer Performance Selections Multicultural Editions 383 Broadway Vocal Scores 477 It’s Easy to Play 569 Score & Sound Masterworks 457 Budget Books 598 Jazz 744 Seasons of Praise 569 CD Sheet Music 609 Jazz Piano Solos Series ® 745 Singalong & Novelty 460 Cheat Sheets 613 Jazz Play-Along Series 513 Sing in the Barbershop 432 Children’s Publications 623 Jewish Quartet 478 The Joy of Series 703 Christian Musician ® 512 Sing with the Choir 530 Classical Collections 521 Keyboard Play-Along Series 352 Songwriter Collections 548 Classical Play-Along 432 Kidsongs Sing-Alongs 746 Standards 541 Classics to Moderns 639 Latin 492 10 For $10 Sheet Music 542 Concert Performer 482 Legendary Series 493 The Ultimate Series 570 Country 483 The Library of… 495 The Ultimate Song 577 Country Music Pages Hall of Fame 643 Love & Wedding 496 Value Songbooks 579 Cowboy Songs -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough,m argins,substandard and improperalignm entcan adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI Universily Microfilms international A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800.'521-0600 Order Nimiber dS2S492 The American Playwrights Theatre: Creating a partnership between commercial and educational theatre as an alternative to Broadway in the 1960s and 1970s Fink, Lawrence Edward, Ph.D. -

Alec Wilder Archive

ALEC WILDER ARCHIVE RUTH T. WATANABE SPECIAL COLLECTIONS SIBLEY MUSIC LIBRARY EASTMAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC UNIVERSITY OF ROCHESTER A revision of the original finding aid, prepared by Colleen V. Fernandez Fall 2017 1 Marian McPartland and Alec Wilder outside Louis Ouzer’s Gibbs Street studio (1970s). Photograph by Louis Ouzer, from Marian McPartland Collection, Box 32, Folder 11, Sleeve 6. Alec Wilder in Duke University band room (undated). Photograph by Louis Ouzer, from Alec Wilder Archive, Series 7 (Photographs), Box 1, Sleeve 11. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Description of the Collection . 5 Description of Series . 8 INVENTORY Series 1: Music Manuscripts (MS) . 10 Sub-series 1: Large instrumental ensemble Sub-series 2: Vocal or instrumental solo with large ensemble Sub-series 3: Instrumental solos, with or without accompaniment Sub-series 4: Chamber music Sub-series 5: Vocal chamber--voice(s) as part of chamber ensemble Sub-series 6: Keyboard--two or more hands Sub-series 7: Vocal solo Sub-series 8: Vocal soloist ensemble with or without accompaniment Sub-series 9: Choral with or without soloists and accompaniment Sub-series 10: Stage works Sub-series 11: Films Scores Sub-series 12: Commercial music Sub-series 13: Sketches Series 2: Printed Music . 88 Series 3: Recordings . 95 Sub-series 1: Reel-to-reel Sub-series 2: NPR recordings Sub-series 3: Discs Sub-series 4: Cassettes Sub-series 5: Videos Sub-series 6: CD's Series 4: Correspondence . 137 Series 5: Personal Papers . 181 Sub-series 1: Poetry Sub-series 2: Prose Series 6: Ephemera . 233 Sub-series 1: Biographical material 3 Sub-series 2: Programs (performances of Wilder's works) Sub-series 3: Listserv documents Sub-series 4: Ancillary materials of various kinds Sub-series 5: Artifacts relating to Wilder’s life Series 7: Photographs . -

Performing Illness in the Late-Nineteenth-Century Theatre

STAGES OF SUFFERING: PERFORMING ILLNESS IN THE LATE-NINETEENTH-CENTURY THEATRE by Meredith Ann Conti Bachelor of Fine Arts, Denison University, 2001 Master of Arts, University of Pittsburgh, 2007 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2011 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Meredith Ann Conti It was defended on April 11, 2011 and approved by Attilio Favorini, PhD, Professor, Theatre Arts Kathleen George, PhD, Professor, Theatre Arts Michael Chemers, PhD, Associate Professor, Carnegie Mellon University, Drama Dissertation Advisor: Bruce McConachie, PhD, Professor, Theatre Arts ii Copyright © by Meredith Ann Conti 2011 iii STAGES OF SUFFERING: PERFORMING ILLNESS IN THE LATE-NINETEENTH-CENTURY THEATRE Meredith Ann Conti, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2011 Few life occurrences shaped individual and collective identities within Victorian society as critically as suffering (or witnessing a loved one suffering) from illness. Boasting both a material reality of pathologies, morbidities, and symptoms and a metaphorical life of stigmas, icons, and sentiments, the cultural construct of illness was an indisputable staple on the late-nineteenth- century stage. This dissertation analyzes popular performances of illness (both somatic and psychological) to determine how such embodiments confirmed or counteracted salient medical, cultural, and individualized expressions of illness. I also locate within general nineteenth-century acting practices an embodied lexicon of performed illness (comprised of readily identifiable physical and vocal signs) that traversed generic divides and aesthetic movements. Performances of contagious disease are evaluated using over sixty years of consumptive Camilles; William Gillette’s embodiment of the cocaine-injecting Sherlock Holmes and Richard Mansfield’s fiendishly grotesque transformations in the double role of Dr. -

News and Events

Volume 25 Number 1 topical Weill Spring 2007 A supplement to the Kurt Weill Newsletter news & news events LoveMusik Ignites Controversy As reported in the Los Angeles Times on 2 May 2007: “Following a pre- view of LoveMusik, Joel Grey approached the legendary director Harold Prince. ‘Hal, I love this show,’ said the actor who starred in Prince’s original Broadway production of Cabaret. ‘But what exactly is it?’” After its 3 May opening night, controversy raged among theater- goers regarding the intellectually challenging show. Apart from near- universal accolades for the stars, Michael Cerveris and Donna Murphy, critical opinion ran the gamut from raves to rotten eggs. “LoveMusik, the new musical portrait of Kurt Weill and Lotte Lenya, is moody, daring, and downright bewildering. Some will view it as stretching the boundaries of musical art form, while others will deem it an exasperating experiment. Regardless of where you fit into that broad continuum (for the record, I’m on the plus side), it is endlessly fascinating.” (Joe Dziemianowicz, Daily News) “Two luminous, life-infused portraits glow from within a dim, heavy frame at the Biltmore Theater. In relating the story of the emotion- ally tortured but highly functional relationship of its main characters, LoveMusik. strives to achieve chilly distance and cozy intimacy in the same breath. As a consequence the show seems to be fighting itself Brecht (David Pittu) with his women: Rachel Ulanet, Ann Morrison, and Judith Blazer every step of the way.” (Ben Brantley, New York Times) “Alfred Uhry had an eye-popping idea for a musical, which, it says, was ‘suggested by the letters of Kurt Weill and Lotte Lenya.’ Maybe. -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: STAGING THE

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: STAGING THE PEOPLE: REVISING AND REENVISIONING COMMUNITY IN THE FEDERAL THEATRE PROJECT Elizabeth Ann Osborne, Doctor of Philosophy, 2007 Directed By: Dr. Heather S. Nathans Department of Theatre The Federal Theatre Project (FTP, 1935-1939) stands alone as the only real attempt to create a national theatre in the United States. In the midst of one of the greatest economic and social disasters the country has experienced, and between two devastating wars, the FTP emerged from the ashes of adversity. One of the frequently lampooned Arts Projects created under the aegis of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal, the FTP lived for four short, turbulent, and exhilarating years. Under the leadership of National Director Hallie Flanagan, the FTP employed more than 13,000 unemployed theatre professionals, brought some much needed emotional support to an audience of more than 30 million, and fought to provide locally relevant theatre for the people of the United States. Yet, how does a national organization create locally relevant theatre in cities and towns throughout this diverse country? Each chapter addresses the same overarching question: How did the FTP develop a relationship with its surrounding communities, and what were the dynamics of that relationship? The regions all dealt with the question in a manner that was unique to their experiences, and which was dependent upon the political, social, cultural, and economic issues that made the communities themselves distinct. Recognizing these differences is vital in understanding both the FTP and the concept of a national theatre in America. This dissertation considers the perceived successes and failures of specific case studies in both urban and rural locations in four of the five major regions, the Midwest, South, East, and West. -

2017 Opera Insider (Pdf)

OPERA INSIDER A Look at the 2017 Festival CENTRAL CITY OPERA SEASON TWO Episodes available starting June 23, and dropped weekly through August 8, 2017 Featuring interviews with artists and others involved in Central City Opera’s 2017 Festival. Listen at your leisure after easily downloading the podcasts directly Hosted and Produced to your computer, tablet or phone by Emily Murdock from CentralCityOpera.org/podcast or from the iPhone Podcasts app or the Android Stitcher app. CentralCityOpera.org TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 Nina Odescalchi Kelly Family Matinee 3 Director’s Letter 4 Education & Community Engagement Programs COMPILED AND WRITTEN BY: Deborah Morrow, 7 Audience Etiquette Emily Murdock, Michael Dixon, Valerie Smith Designed by Melissa Rick 9 Words You Should Know EDUCATION AND COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT 12 Festival Schedule PERSONNEL: Director – Deborah Morrow 13 Festival Extras Associate Director and Podcast Host/Producer – Emily Murdock 14 CARMEN Podcast Intern – CL Morden Production Assistant – Kenny Martinez 24 COSÌ FAN TUTTE Resident Teaching Artist – Roger Ames 34 THE BURNING FIERY FURNACE General and Artistic Director – Pelham G. Pearce 42 GALLANTRY CentralCityOpera.org Central City Opera Box Office 303.292.6700 48 CABILDO CentralCityOpera.org 2017 Opera Insider 1 Nina Odescalchi Kelly Family Matinee of CARMEN Tuesday, August 1, 2017 | 2:30 pm CENTRAL CITY OPERA PRESENTS the family friendly matinee in the Central City Opera House, performed by members of the Bonfils-Stanton Foundation Artists Training Program. Pre-show activities and a post-show autograph signing session with the stars. Tickets now on sale. Order today! CentralCityOpera.org | 303.292.6700 WELCOME TO THE 2017 OPERA INSIDER. -

Opera at Columbia: a Shining Legacy

Opera at Columbia: A Shining Legacy Margaret Ross Griffel Introductory Note: Opera has always been central to my life. Listening to the Saturday afternoon broadcasts from the Metropolitan Opera was a ritual in my parents' home, and we talked about our visits to the Met (albeit in the "nosebleed" seats) for weeks afterward. My love for opera was further nourished by my years at New York City's High School of Music and Art, then some twenty blocks north of Columbia University, during which time Handel oratorios were semistaged at the school's major concerts and Aaron Copland's The Second Hurricane (1937) was revived at Carnegie Hall in a 1960 performance by M&A students conducted by Leonard Bernstein. In the 1960s, it was my good fortune to attend Barnard College and then do graduate studies in musicology at Columbia, where chances to hear contemporary as well as older operas abounded and opera compos ers such as Douglas Moore, Otto Luening, Henry Cowell, and Jack Beeson were members of the faculty. Sadly, such opportunities diminished in the following decades, breaking Columbia's tradition of being a major source for the creation and performance of operas, which had reached its height in the 1940s and 1950s-the heyday of the Columbia Opera Workshop. After a brief history of the Workshop, the present article examines what it was like to be an opera-loving student at Columbia in the mid -1960s when Current Musicology was launched. Surrounded by the prominent compos ers mentioned above and other former participants of the Workshop who still taught courses in the Department of Music, including Willard Rhodes and Howard Shanet, we students had the chance to hear new and rarely performed works on campus or at nearby music conservatories and opera houses. -

Something About Librettos

SOMETHING ABOUT LIBRETTOS By Douglas Moore OPERA NEWS Sept. 30th, 1961 There is a skit by William Saroyan called Opera Opera, a piece full of silliness and ridiculous repetitions. Many would agree that it is only a mild distortion of the real thing. Much as the American public likes opera, it has little respect for the libretto as a work of art or even as a theatrical piece. This is perhaps natural. Granted that there are a number of librettos of quality in the standard repertory, our audiences used to hear them either in a foreign language or in translation so inept as to destroy their effectiveness. The librettos written in English for the operas by American composers produced at the Metropolitan during the Gatti-Gasazza regime were, with one or two exceptions, pretentious and stuffy. At a time when the theater was in a fresh and lively state, they took as their models the dramatic ideas of nineteenth-century opera. Edward Johnson once remarked that American composers and their librettists approached their work with imaginations paralyzed by the glamor of the past. It never seemed to occur to them that there should be any relation to the living theater. What was right for Rossini and Verdi would be right for them. They forgot that the nineteenth-century composers were writing for the contemporary theater. Today the situation is much better. Skillful translators like the Martins, the Meads, Edward Dent, W.H. Auden and John Gutman have made a part of the standard repertory available in English. Although a large public seems to prefer opera in the original language, translated operas are making headway and audiences are discovering new satisfactions in the familiar repertory. -

Agitprop to Colbertisms

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2008 Entertainment News: Agitprop to Colbertisms Chanelle Renee Vigue Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/670 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Chanelle Renee Vigue 2008 All Rights Reserved ENTERTAINMENT NEWS: FROM AGITPROP TO COLBERTISMS A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts at Virginia Commonwealth University. by CHANELLE RENEE VIGUE BFA Theatre Education, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2006 Director: DR. NOREEN C. BARNES DIRECTOR OF GRADUATE STUDIES, DEPARTMENT OF THEATRE Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia May 2008 ii Acknowledgement I would like to thank my family for giving me every opportunity to succeed. I especially thank my father for instilling in me an uncompromising work ethic and dedication to those things in which I believe and my mother for giving me her determination. Without the loving support of Faye Vigue, John Elliott, and my entire Elliott family, Noreen C. Barnes, Marvin Sims, Aaron Anderson, Janet Rodgers and the -

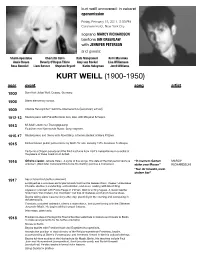

Kurt Weill Uncovered: in Cabaret Operamission

kurt weill uncovered: in cabaret operamission Friday, February 18, 2011, 8:00 PM Gershwin Hotel, New York City soprano MARCY RICHARDSON baritone IAN GREENLAW with JENNIFER PETERSON and guests: Sharin Apostolou Charlotte Cohn Kate Mangiameli Kerri Marcinko Annie Rosen Beverly O’Regan Thiele Amy van Roekel Lisa Williamson Ross Benoliel Liam Bonner Stephen Bryant Karim Sulayman Jorell Williams KURT WEILL (1900-1950) year event song artist 1900 Born Kurt Julian Weill, Dessau, Germany. 1906 Starts elementary school. 1909 Attends Herzogliche Friedrichs-Oberrealschule [secondary school]. 1912-13 Studies piano with Franz Brückner and, later, with Margaret Schapiro 1913 Mi Addir: Jüdischer Trauungsgesang. Es blühen zwei flammende Rosen. Song fragment. 1915-17 Studies piano and theory with Albert Bing, a former student of Hans Pfitzner. 1915 Earliest known public performance by Weill: Für uns, January 1915, Dessauer Feldkorps. Performs a Chopin prelude and the third nocturne from Liszt’s Liebesträume in a recital at the palace of Duke Friedrich of Anhalt. 1916 Ofrahs Lieder, Jehuda Halevi. A cycle of five songs. The date of the first performance is “In meinem Garten MARCY unknown. (Weill later considered this to be his starting point as a composer.) stehn zwei Rosen” RICHARDSON “Nur dir fürwahr, mein stolzer Aar” 1917 Das schöne Kind (author unknown) Employed as a volunteer accompanist and coach at the Dessau Court Theater. Undertakes intensive studies in conducting, orchestration, and score-reading with Albert Bing. Appears in concert with Emilie Feuge in Cöthen. Weill is writing fugues. A music teacher finds them “too modern, too chromatic” but free of mistakes and full of musical ideas. -

Introduction: the “People's Theatre”: Creating An

Notes INTRODUCTION: THE “PEOPLE’S THEATRE”: CREATING AN AUDIENCE OF MILLIONS 1. “200,000 New Words Credited to U.S.,” New York Times, November 10, 1936, 23. 2. Hallie Flanagan, Arena (New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1940), 134. 3. Charles H. Meredith, “America Sings,” Federal Theatre 1, no. 6 (1936): 12. 4. Mark Franko, The Work of Dance: Labor, Movement, and Identity in the 1930s (Middleton, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2002), 22–3. 5. For more on Hallie Flanagan, see Flanagan, Arena; Jane de Hart Mathews, The Federal Theatre, 1935–1939: Plays, Relief, and Politics (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1967); and Joanne Bentley, Hallie Flanagan: A Life in the American Theatre (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1988). 6. The Historical Records Survey would join the ranks of Federal One under the jurisdiction of the Federal Writers’ Project in November 1935; it became an independent member of Federal One in October 1936. William F. McDonald, Federal Relief Administration and the Arts (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1969), 214. 7. Flanagan, Arena, 23. 8. House Committee on Patents. Department of Science, Art and Literature: Hearings before the Committee on Patents. Transcript, 75th Congress, 3rd sess., 1938 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1938), 93. 9. Burgess Meredith first compared the cost of the FTP to the cost of building a battleship in December 1937 in Equity. At that time, FTP expenditures approximated 22 million dollars, or about one- half the price of a battleship. Flanagan, Arena, 434–6. 10. Quoted in John O’Connor and Lorraine Brown, Free, Adult, Uncensored: The Living History of the Federal Theatre Project (Washington, DC: New Republic Books, 1978), 2.