Exercise and Progressive Supranuclear Palsy: the Need for Explicit Exercise Reporting Susan C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gait Training to Improve Functional Mobility in A

GAIT TRAINING TO IMPROVE FUNCTIONAL MOBILITY IN A CHILD WITH CEREBRAL PALSY A Doctoral Project A Comprehensive Case Analysis Presented to the faculty of the Department of Physical Therapy California State University, Sacramento Submitted-in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHYSICAL THERAPY by Bhumisha Patel SUMMER 2016 ©2016 Bhumisha Patel ALL RIGHTS RESERVED 11 GAIT TRAINING TO IMPROVE FUNCTIONAL MOBILITY IN A CHILD WITH CEREBRAL PALSY A Doctoral Project by Bhumisha Patel _____, Second Reader Katrin Mattern-Baxter, PT, DPT, PCS ------, Third Reader Clare Lewis, PT, PsyD, MPH, MTC i ?2-/ulv Date Ill Student: Bhumisha Patel I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and that this project is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for the project. -------' Department Chair PT, EdD Department of Physical Therapy lV Abstract of GAIT TRAINING TO IMPROVE FUNCTIONAL MOBILITY IN A CHILD WITH CEREBRAL PALSY by Bhumisha Patel A patient with c~rebral palsy was seen for physical therapy treatment for 12 sessions from 3110/15 to 5/08/15. Treatment was provided by a student physical therapist under the supervision of a licensed physical therapist. The patient was evaluated at the initial encounter with the Peabody Developmental Motor Scales to measure gross and fine motor delays, the Six Minute Walk Test to measure gait endurance, the Gross Motor Function Measure-66 to measure and predict the gross motor development, and the 10 Meter Walk Test to measure the gait velocity. Following the evaluation a plan of care was established. -

What Every Social Worker Physical Therapist Occupational

What Every Social Worker Physical Therapist Occupational Therapist Speech-Language Pathologist Should Know About Progressive Supranuclear Palsy (PSP) Corticobasal Degeneration (CBD) Multiple System Atrophy (MSA) A Comprehensive Guide to Signs, Symptoms, and Management Strategies DISEASE SUMMARIES at a glance Progressive Supranuclear Palsy (PSP) • Rare neurodegenerative disease, the most common parkinsonian disorder after Parkinson’s disease (PD) • Originally described in 1964 as Steele-Richardson-Olszewski syndrome • Often mistakenly diagnosed as PD due to the similar early symptoms • Symptoms include early postural instability, supranuclear gaze palsy (paralysis of voluntary vertical gaze with preserved reflexive eye movements), and levodopa-nonresponsive parkinsonism • Onset of symptoms is typically symmetric • Pathologically classified as a tauopathy (abnormal accumulation in the brain of the protein tau) • Five to seven cases per 100,000 people • Slightly more common in men • Average age of onset is 60–65 years, but can occur as early as age 40 • Life expectancy is five to seven years following symptom onset • No cure or effective medication management Signs and Symptoms • Early onset gait and balance problems • Clumsy, slow, or shuffling gait 2 • Lack of coordination • Slowed or absent balance reactions and postural instability • Frequent falls (primarily backward) • Slowed movements • Rigidity (generally axial) • Vertical gaze palsy • Loss of downward gaze is usually first • Abnormal eyelid control • Decreased blinking with “staring” -

Management of Balance and Gait in Older Individuals with Parkinson's Disease Ryan P

Washington University School of Medicine Digital Commons@Becker Physical Therapy Faculty Publications Program in Physical Therapy 2011 Management of balance and gait in older individuals with Parkinson's disease Ryan P. Duncan Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis Abigail L. Leddy Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis Gammon M. Earhart Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/pt_facpubs Recommended Citation Duncan, Ryan P.; Leddy, Abigail L.; and Earhart, Gammon M., "Management of balance and gait in older individuals with Parkinson's disease" (2011). Physical Therapy Faculty Publications. Paper 32. http://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/pt_facpubs/32 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Program in Physical Therapy at Digital Commons@Becker. It has been accepted for inclusion in Physical Therapy Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Becker. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Management of Balance and Gait in Older Individuals with Parkinson Disease 2 Duncan R.P.1, Leddy A.L.1, Earhart G.M.1,2,3 3 1Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine, Program in Physical Therapy 4 2Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine, Department of Anatomy & Neurobiology 5 3Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine, Department of Neurology 6 7 Corresponding Author: 8 Gammon M. Earhart, PhD, PT 9 Washington University School of Medicine 10 Program in Physical Therapy 11 Campus Box 8502 12 4444 Forest Park Blvd. 13 St. Louis, MO 63108 14 314-286-1425 15 Email: [email protected] 16 17 Summary 18 Difficulties with walking and balance are common among people with Parkinson disease 19 (PD). -

WALK the WALK: High-Intensity Gait Training in Stroke Rehabilitation

Photo provided by Mary Free Bed Rehabilitation Hospital - a collaborative research partner THE INSTITUTE FOR KNOWLEDGE TRANSLATION IN REHABILITATION WALK THE WALK: High-Intensity Gait Training in Stroke Rehabilitation 2019 DATES: Mentoring (optional): 8 p.m. Nov. 18, Dec. 9 and Jan. 20 Online Training: Sept. 9–23 Community of Practice Meeting (optional, access for one year): In-Person Training: Sept. 28–29 9 p.m. First Monday of the month Mary Free Bed Professional Building Institute for Knowledge Translation Meijer Conference Center 275 Medical Drive #243 350 Lafayette Ave. SE Carmel, IN 46082 Grand Rapids, MI 49503 www.knowledgetranslation.org 317.660.1185; [email protected] ABOUT THE INSTITUTE FOR • Online course on high-intensity gait training (5.0 CEUs) KNOWLEDGE TRANSLATION • In-person training on the gait-training program and knowledge translation concepts (1.5 days) Research indicates that traditional methods of providing education, such as in-person and online continuing • High-Intensity Variable Gait Training knowledge tools (i.e. cheat sheets) education courses, may improve knowledge and skill, but they do very little to change the care provided in clinical • Three post-course online group mentoring sessions (three one-hour sessions) practice. The Institute for Knowledge Translation provides an innovative and evidence-based solution to maximize the • Access to the program faculty for six months for KT impact of education and quality-improvement efforts. The support iKT offers a variety of evidence-based knowledge translation • Participation in an online community of practice for one programs, from comprehensive educational packages to help year, which will offer implementation support from peers and experts. -

Analysis and Equipment Selection Sally Mallory, PT, ATP, CPST [email protected] Course Outline

Gait Analysis and Equipment Selection Sally Mallory, PT, ATP, CPST [email protected] Course Outline Importance of independent mobility Factors impacting functional mobility Analysis of gait cycle Phases of gait Shank & thigh kinematics Considerations for equipment selection BWSTT treadmill training vs ground training Ambulation equipment types Gait analysis with instrumentation & case study 3 During Ambulation • The whole body is active • Bones, joints and muscles, nerves, senses, heart and lungs work together and movements are coordinated. • To be able to walk, head and trunk control together with balance and active use of arms and legs are needed. 4 Importance of Independent Mobility • Increases level of engagement in educational and recreational activities • Promotes problem solving skills • Enhances quality of interactive behavior with other children, adults • Increases exploration of environment • Promotes cognitive, perceptual and visual spatial skills by learning to navigate around obstacles, avoid stairs or other drop offs • Promotes healthy functioning of physiological systems (heart, lungs, GI, bladder, bones) • Increases self confidence • Reduces learned helplessness 5 Importance of Early Mobility • Immobility associated with “Learned Helplessness” • Established by 4 years of age in children without functional mobility (Butler, 1991; Safford & Arbitman, 1975, Lewis & Goldberg ,1969) • Decreased curiosity & initiative • Poor academic achievement • Poor social interaction skills (Kohn,1 977) • Passive, dependent behavior -

UNIVERSITY of FLORIDA Center for Movement DISORDERS

UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA center for movement disorders and neurorestoration A world leader in Tyler’s Hope Center for a Dystonia Cure, and an NIH- designated headquarters of the nationwide Clinical movement disorders Research Consortium for Spinocerebellar Ataxias. and neurorestoration Comprehensive Care Center The University of Florida Center for Movement Disorders 5000+ patients seen and actively followed and Neurorestoration is founded on the philosophy that integrated, interdisciplinary care is the most effective Other Dxs approach for patients with movement disorders. The 1,396 PD 1,692 Center, therefore, delivers motor, cognitive and behavioral diagnoses and treatments in one centralized location. Care Ataxia 48 is coordinated and provided by leading specialists for a Tics 102 Chorea 69 159 431 myriad of advanced medical and surgical services. Psychogenic 267 ET Atypical 300 509 Parkinsonism Built on the expertise of University of Florida faculty and Parkinsonism Dystonia researchers from 14 different specialty and subspecialty areas, the Center has earned a reputation for excellence The patients we treat that makes it an international destination for patient care, Patients come to the Center from every corner of the globe research and teaching in the field of movement disorders and they are referred by physicians who recognize that and neurorestoration. At UF, patients have access to the movement disorders are more than neurological problems latest clinical/translational research studies, as well as the and that the challenges they present are more than medical. opportunity to contribute to future research. Since its At the Center, we care for all aspects of the patient’s creation less than a decade ago, the Center has treated disease through the use of coordinated interdisciplinary more than 5,000 patients, the majority of whom continue care, including: to be followed by multiple specialties, creating one of the • Parkinson’s Disease largest databases on movement disorder treatments • Tremor disorders (essential tremor, outflow tremor, available anywhere. -

Hypoxic-Ischemic Brain Injury: Movement Disorders and Clinical Implications

Hypoxic-Ischemic Brain Injury: Movement Disorders and Clinical Implications By: Carolyn Tassini, PT, DPT, CBIS, NCS Supervisor, Rehabilitation Services March 27, 2019 Disclosures • Carolyn Tassini, PT, DPT, CBIS, NCS – Nothing to disclose • Additional credit for this presentation goes to Kimberly Miczak, PT, NCS Following this session: • Participants will appreciate mechanisms underlying motor, cognitive and visual impairments following hypoxic-ischemic brain injury. • Participants will utilize current evidence from movement disorder literature in developing treatment plan for individuals following hypoxic- ischemic brain injury. • Participants will recognize the importance of transdisciplinary team in maximizing treatment and outcomes for individuals recovering from hypoxic- ischemic brain injury. Introduction • What is a hypoxic or anoxic brain injury? ◦ Hypoxic-Ischemic brain injury • Common Causes • Cardiorespiratory arrest • Respiratory failure • Drug overdose • Carbon monoxide poisoning • Drowning/strangulation • Primary vs secondary injury Image from: neurolove.tumblr.com Background Info • No national data available on the prevalence of HI- BI • Peak frequency in males aged 60-years (r/t cardiac) and females in their late 20’s r/t suicide and parasuicide/self-harm attempts (Fitzgerald 2010) • Can range from mild to severe • HI-BI vs TBI rehab course: • slower progress • poorer outcome • more likely to DC to residential facility vs home (Fitzgerald 2010) Mechanism of Injury • Cardiorespiratory- hypoxia with ischemia ◦ Reperfusion -

Gait Training: Overground, Treadmill and Early Intervention | Rifton Webinar | References

Gait Training: Overground, Treadmill and Early Intervention A sampling of related articles published in peer-reviewed journals. Note: Research references on robotic-assisted gait training are not included here. Topics Overground • Adult Rehab • Comparison to Treadmill (Adult and Pediatric) • Pediatric • Postural Strength/Function/Activity Treadmill • Cerebral Palsy • Spinal Cord Injury • Stroke • Systematic Reviews Early intervention • Cerebral Palsy • Down Syndrome • Implications for development Overground Adult Rehab Fox EJ, Tester NJ, Butera KA, Howland DR, Spiess MR, Castro-Chapman PL, Behrman AL. (2017) Retraining walking adaptability following incomplete spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord Ser Cases. Dec 14;3:17091. Free Full Text https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5803746/ Hamonet J, Daviet J, Bordes J, Cugy E, Dalmay F, Salle Chu Limoges J. (2011) Comparative study on post-effect after Gait Trainer and after over-ground training in gait symmetry in stroke patients. Annals of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine. 54(Suppl 1):e235. Free Full Text https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S187706571100412X Download PDF McCain K, Shearin S. (2017) A Clinical Framework for Functional Recovery in a Person With Chronic Traumatic Brain Injury: A Case Study. J Neurol Phys Ther. 41(3):173-181 Abstract https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=28628551 Peurala SH, Tarkka IM, Pitkanen K, Sivenius J (2005) The effectiveness of body weight-supported gait training and floor walking in patients with chronic stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 86(8):1557-64. Free Full Text http://www.archives-pmr.org/article/S0003-9993(05)00210-8/fulltext States RA, Salem Y, Pappas E. -

Neurology Section POSTER Presentations

Abstracts Neurology Section POSTER Presentations Found 155 Abstracts TITLE: The reliability and validity of the ‘Sway Sled’®: a new clinical measure of stability limits. AUTHORS/INSTITUTIONS: L.K. Allison, R. Shoaf, M. van der Linde, Physical Therapy, East Carolina Univ, Greenville, NC| ABSTRACT BODY: Purpose/Hypothesis : Decreased stability limits are a major risk factor for falls in older adults. Computerized forceplate testing (LOS) is the gold standard stability limits test, but is costly. The Multi-Directional Functional Reach (MDFR) test costs less, but may not be a valid measure. The new Sway Sled® (SS) is an inexpensive, easy clinical measure of stability limits that may offer better measures than the MDFR. The purpose(s) of this study are to test the reliability and validity of the Sway Sled® in young and older healthy adults, and compare these to the MDFR. Number of Subjects : Subjects were healthy young (N=22; 12 F, mean age = 24.9 yrs, +7) and older adults (N=9; 2 F, mean age= 77.1 yrs, +26). Materials/Methods : The SS is a lightweight, low-friction device placed on parallel bars with a height adjustable bar at the ASIS. Subjects slide the SS by weight-shifting. The distance between start and stop positions is measured. Subjects performed the SS first, then the LOS and MDFR in random order. For each group, maximum volitional sway excursion (ME) scores in all trials (3) in each direction (4; anterior, posterior, left, right) for each test (3) were compared using a RM-ANOVA (p=0.05) with post-hoc Paired t-tests (p=0.0167). -

Effect of Automated Locomotor Training on Gait in Children with Cerebral Palsy: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

World Journal of Sport Sciences 14(2): 34-41, 2019 ISSN 2078-4724 © IDOSI Publications, 2019 DOI: 10.5829/idosi.wjss.2019.34.41 Effect of Automated Locomotor Training on Gait in Children with Cerebral Palsy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Sally E. Morsy, Elham E. Salem and Eman I. Elhadidy Department of Physical Therapy for Pediatrics, Faculty of Physical Therapy, Cairo University, Egypt Abstract: Objective: to investigate and summarize the most updated evidence on the effectiveness of automated locomotor training on gait and other gait-related functions in children with cerebral palsy (CP). Data sources: PubMed, Cochrane Library, Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro), EBSCO, Ovid and Google Scholar were searched from inception till July 2019. Study selection: The selected studies were randomized controlled trials for children with CP received robotic assisted gait training (RAGT) as an intervention while reporting outcome measures relating to gait. Data extraction: The information was extracted from the selected articles using the descriptive-analytical method. Two authors independently screened articles, extracted data and assessed the methodological quality using PEDro scale, with any confliction resolved by the third author. Results: Out of 968 papers screened, 7 studies with 172 participants met the inclusion criteria. The quality of studies ranged from 4 to 7 out of 10 on PEDro score. Included studies reported some positive benefits for RAGT with children with CP, specifically by increasing walking speed and endurance and improving gross motor functions, However a meta-analysis did not confirm these findings. Conclusion: Meta-analysis revealed a non-significant difference between the experimental groups and control groups for change in gait speed, dimension E and D of gross motor function measure (GMFM). -

Background and Aims Gait Impairment

Background and aims Gait impairment and consecutively reduced mobility are typical features of idiopathic Parkinson´s disease (PD) and atypical parkinsonian disorders (APDs). However, these features develop earlier and are more pronounced in APDs such as Parkinson variant multiple system atrophy (MSA-P) [1]. The emergence of gait disorders with instability, freezing and falls represents a major motor milestone in the natural history of parkinsonian syndromes indicating a transition to sustained disability and reduced quality of life. Impaired physical activity and sedentary behavior are associated with reduced walking bouts and increased time spent in sitting or lying posture [2], resulting in disabling consequences for daily life activities and therefore creating a vicious cycle, which is linked to higher mortality rate also in normal elderly people [3]. On the contrary, increased activity levels can sustain independence, delay onset of decline and lower fall risk [4, 5]. A special characteristic of MSA patients is their resistance to dopaminergic therapy. Also in PD patients that typically benefit from dopaminergic treatment, in advanced stages, where gait impairment is increasing, dopaminergic intervention becomes less effective. Importantly, for gait impairment in PD non-pharmacological interventions are more and more recognized as complementary treatment options [6]. Up to now, many exercise-based interventions are available for PD, ranging from community exercises like dancing and tai chi to complex computer-based training options and the scientific evidence for their efficacy is growing [6-8]. For instance, Cusso et al. described the positive impact of physical activity on motor as well as non-motor symptoms[8] and there is strong evidence that freezing of gait can be effectively overcome using cueing strategies[9]. -

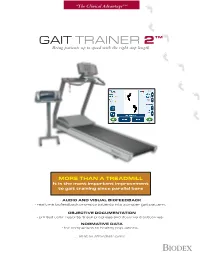

The Biodex Gait Trainer 2 Compares Step Length, Step Speed and Or -3 to -12% Grade Step Symmetry to Age and Gender-Based Normative Data

“The Clinical Advantage” ™ GAIT TRAINER 2™ Bring patients up to speed with the right step length MORE THAN A TREADMILL It is the most important improvement to gait training since parallel bars • AUDIO AND VISUAL BIOFEEDBACK - real time biofeedback prompts patients into a proper gait pattern. • OBJECTIVE DOCUMENTATION - printed color reports track progress and document outcomes. • NORMATIVE DATA - for comparison to healthy populations. ... all at an affordable price. BIODEX MORE THAN JUST A TREADMILL It is the most important improvement to gait training since the parallel bars. ™ Touch-Screen Display easy GAIT TRAINER 2 to see, easy to use, high-resolution color touch-screen LCD display Bring patients up to speed with the right step length provides instant biofeedback with audio-visual prompts to the patient FEATURES Heart Rate Monitoring using telemetry or contact • Audio and Visual Biofeedback feature to accommodate - real time biofeedback prompts patients into a proper gait pattern unweighing harnesses • Objective Documentation - printed color reports track progress and document outcomes - ideal for insurance reimbursement Sturdy Functional • Normative Data Support Bar - for comparison to healthy populations • High Resolution Color Touch-Screen LCD Display - easy to see and use • Patient Data Storage - maintains records to track progress and issue reports for up to 500 patients • Data Export – serial interface allows download of patient data to computer for archiving, reporting or export as a CSV file • Footfall Data Export - a versatile