The Arab Spring's Four Seasons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Geneva Conventions (Amendment) Act 2003

THE GENEVA CONVENTIONS (AMENDMENT) ACT 2003 Act No. 2 of 2003 I assent KARL AUGUSTE OFFMANN President of the Republic 7th May 2003 ___________ ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS Section 1. Short title 2. Interpretation 3. Section 2 of principal Act amended 4. Section 3 of principal Act amended 5. Section 5 of principal Act amended 6. Section 6 of principal Act amended 7. Section 8 of principal Act amended 8. Section 9 of principal Act repealed and replaced Date In Force: ________ An Act To amend the Geneva Conventions Act ENACTED by the Parliament of Mauritius, as follows – 1. Short title This Act may be cited as the Geneva Conventions (Amendment) Act 2003. 2. Interpretation In this Act - "principal Act" means the Geneva Conventions Act. 3. Section 2 of principal Act amended Section 2 of the principal Act is amended – (a) by inserting in their appropriate alphabetical places, the following definitions - "Court" does not include a court-martial or other military court; "Protocol I” means the Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts (Protocol I), done at Geneva on 10 June 1977; "Protocol II" means the Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Protection of victims of Non-International Armed Conflicts (Protocol II), done at Geneva on 10 June 1977; "Protocols" means Protocol I and Protocol II; (b) in the definitions of "protected internee" and "protecting power", by adding immediately after the words "Fourth Convention", the words "or Protocol I"; (c) in the definition of "protected prisoner of war", by adding immediately after the words "Third Convention", the words "or a person who is protected as a prisoner of war under Protocol I". -

State of Anarchy Rebellion and Abuses Against Civilians

September 2007 Volume 19, No. 14(A) State of Anarchy Rebellion and Abuses against Civilians Executive Summary.................................................................................................. 1 The APRD Rebellion............................................................................................ 6 The UFDR Rebellion............................................................................................ 6 Abuses by FACA and GP Forces........................................................................... 6 Rebel Abuses....................................................................................................10 The Need for Protection..................................................................................... 12 The Need for Accountability .............................................................................. 12 Glossary.................................................................................................................18 Maps of Central African Republic ...........................................................................20 Recommendations .................................................................................................22 To the Government of the Central African Republic ............................................22 To the APRD, UFDR and other rebel factions.......................................................22 To the Government of Chad...............................................................................22 To the United Nations Security -

Geneva Conventions

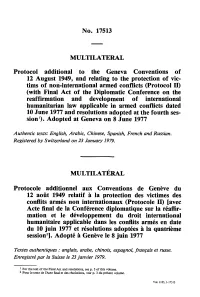

No. 17513 MULTILATERAL Protocol additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the protection of vic tims of non-international armed conflicts (Protocol II) (with Final Act of the Diplomatic Conference on the reaffirmation and development of international humanitarian law applicable in armed conflicts dated 10 June 1977 and resolutions adopted at the fourth ses sion1)- Adopted at Geneva on 8 June 1977 Authentic texts: English, Arabic, Chinese, Spanish, French and Russian. Registered by Switzerland on 23 January 1979. MULTILATERAL Protocole additionnel aux Conventions de Genève du 12 août 1949 relatif à la protection des victimes des conflits armés non internationaux (Protocole II) [avec Acte final de la Conférence diplomatique sur la réaffir mation et le développement du droit international humanitaire applicable dans les conflits armés en date du 10 juin 1977 et résolutions adoptées à la quatrième session2]. Adopté à Genève le 8 juin 1977 Textes authentiques : anglais, arabe, chinois, espagnol, fran ais et russe. Enregistr par la Suisse le 23 janvier 1979. 1 For the text of the Final Act and resolutions, see p. 3 of this volume. 2 Pour le texte de l'Acte final et des résolutions, voir p. 3 du présent volume. Vol. 1125,1-I7513 610 United Nations — Treaty Series • Nations Unies — Recueil des Traités 1979 PROTOCOL ADDITIONAL1 TO THE GENEVA CONVENTIONS OF 12 AUGUST 1949,2 AND RELATING TO THE PROTECTION OF VICTIMS OF NON-INTERNATIONAL ARMED CONFLICTS (PROTOCOL II) CONTENTS Preamble Part I. Scope of this Protocol Article 14. Protection of objects indispensable Article 1 . Material field of application to the survival of the civilian population Article 2. -

The UK's Relations with Saudi Arabia and Bahrain

House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee The UK’s relations with Saudi Arabia and Bahrain Fifth Report of Session 2013–14 Volume II Additional written evidence Ordered by the House of Commons to be published 12 November 2013 Published on 22 November 2013 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited The Foreign Affairs Committee The Foreign Affairs Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and its associated agencies. Current membership Rt Hon Richard Ottaway (Conservative, Croydon South) (Chair) Mr John Baron (Conservative, Basildon and Billericay) Rt Hon Sir Menzies Campbell (Liberal Democrat, North East Fife) Rt Hon Ann Clwyd (Labour, Cynon Valley) Mike Gapes (Labour/Co-op, Ilford South) Mark Hendrick (Labour/Co-op, Preston) Sandra Osborne (Ayr, Carrick and Cumnock) Andrew Rosindell (Conservative, Romford) Mr Frank Roy (Labour, Motherwell and Wishaw) Rt Hon Sir John Stanley (Conservative, Tonbridge and Malling) Rory Stewart (Conservative, Penrith and The Border) The following Members were also members of the Committee during the parliament: Rt Hon Bob Ainsworth (Labour, Coventry North East) Emma Reynolds (Labour, Wolverhampton North East) Mr Dave Watts (Labour, St Helens North) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the internet via www.parliament.uk. Publication The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. All publications of the Committee (including news items) are on the internet at www.parliament.uk/facom. -

Accession of the Republic of Seychelles to the Geneva Conventions and to the Protocols

As Head of the ICRC Legal Division and later Director of the Department of Principles and Law, he was entrusted with the task of organizing the International Red Cross Conferences which have been held regularly since 1948. He played an important part in the Diplomatic Conference on the Reaffirmation and Development of International Humanitarian Law, from 1974 to 1977, and in the work of the International Institute of Humanitarian Law in San Remo. On several occasions, he contributed articles to the Inter- national Review of the Red Cross. After retiring from the ICRC, he accepted the mandate entrusted to him by the Secretary-General of the United Nations to chair the Commission on the Tracing of Missing Persons in Cyprus. All who had the privilege of working with him will remember him as a man of exceptional intelligence, high-minded, always friendly and smiling, endowed with the ability of always finding the right word to put even the most reserved people at ease and with the skill of finding the turns of phrase which eventually won everyone's approval. The ICRC is fully aware of its debt to this faithful servant of the Red Cross and has conveyed its deepest sympathy to his family. Accession of the Republic of Seychelles to the Geneva Conventions and to the Protocols The Republic of Seychelles deposited with the Swiss Government, on 8 November 1984, its instruments of accession to the four Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949 and to the Additional Protocols I and II adopted on 8 June 1977. These treaties will enter into force for the Republic of Seychelles on 8 May 1985. -

United Arab Emirates 2013 Human Rights Report

UNITED ARAB EMIRATES 2013 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The United Arab Emirates (UAE) is a federation of seven semiautonomous emirates with a resident population of approximately 9.2 million, of whom an estimated 11.5 percent are citizens. The rulers of the seven emirates constitute the Federal Supreme Council, the country’s highest legislative and executive body. The council selects a president and a vice president from its membership, and the president appoints the prime minister and cabinet. In 2009 the council selected Sheikh Khalifa bin Zayed al- Nahyan, ruler of Abu Dhabi Emirate, to a second five-year term as president. The emirates are under patriarchal rule with political allegiance defined by loyalty to tribal leaders, leaders of the individual emirates, and leaders of the federation. There are limited democratically elected institutions, but no political parties. A limited appointed electorate participates in periodic elections for the Federal National Council (FNC), a consultative body that can examine, review, and recommend changes to legislation, consisting of 40 representatives allocated proportionally to each emirate based on population. In 2011 the appointed electorate of approximately 129,000 citizens elected 20 FNC members, and the rulers of the individual emirates appointed the other 20. Citizens can express their concerns directly to their leaders through traditional consultative mechanisms such as the open majlis (forum). Topics of legislation can also emerge through discussions and debates in the FNC. While authorities maintained effective control over the security forces, there were some media reports of human rights abuses by police. The three most significant human rights problems were citizens’ inability to change their government; limitations on citizens’ civil liberties (including the freedoms of speech, press, assembly, association, and internet use); and arbitrary arrests, incommunicado detentions, and lengthy pretrial detentions. -

In Colonial Bahrain: Beyond the Sunni / Shia Divide

THREATS TO BRITISH “PROTECTIONISM” IN COLONIAL BAHRAIN: BEYOND THE SUNNI / SHIA DIVIDE A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Arab Studies By Sarah E. A. Kaiksow, M.St. Washington, D.C. April 24, 2009 I would like to thank Dr. Judith Tucker and Dr. Sara Scalenghe for inspiration and encouragement. ii Copyright 2009 by Sarah E. A. Kaiksow All Rights Reserved iii TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction 1 Research Focus 2 Periodization 7 Archives 9 II. Background 12 The al-Khalifa and the British 12 Economy & Society of an island thoroughfare 17 Trade, pearls, date gardens, fish, and fresh water springs 17 Baharna, Huwala, Persians, Najdis, Thattia Bhattias, and Jews 20 III. Threats on the Ground: Saud-Wahabis in the Nineteenth Century 24 Uncertain allies (1830-1831) 24 First interventions (1850-1850) 26 Saud-Wahabis, Persia, and the Ottomans (1860-1862) 29 Distinctive registers 33 A new role for Britain (circa 1920) 34 The case for internal “reform” (1920-1923) 36 The “Najdi” crisis (April, 1923) 44 Debating the threats (May, 1923) 48 Forced succession (May 26, 1923) 50 Pearling industry and reforms (1915-1923) 52 Resistance to colonial reform (June – September, 1923) 55 Dawasir Exodus (October, 1923) 59 Consolidating the state (1926-1930) 61 IV. Persia and State Consolidation in the Twentieth Century 64 V. Conclusion 66 Bibliography 75 iv I. Introduction In the early months of 1923, the Under Secretary -

Model Legislation on Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict”

PERMANENT COUNCIL OEA/Ser.G CP/doc.4847/13 17 March 2013 Original: Spanish NOTE FROM THE CHAIR OF THE INTER-AMERICAN JURIDICAL COMMITTEE TO THE CHAIR OF THE PERMANENT COUNCIL TRANSMITTING THE REPORT ON “MODEL LEGISLATION ON PROTECTION OF CULTURAL PROPERTY IN THE EVENT OF ARMED CONFLICT” COMISSÃO JURÍDICA INTERAMERICANA COMITÉ JURÍDICO INTERAMERICANO INTER‐AMERICAN JURIDICAL COMMITTEE COMITÉ JURIDIQUE INTERAMÉRICAIN ORGANIZATION OF AMERICAN STATES Av. Marechal Floriano, 196 ‐ 3o andar ‐ Palácio Itamaraty – Centro Rio de Janeiro, RJ ‐ 20080‐002 ‐ Brasil Tel.: (55‐21) 2206‐9903; Fax (55‐21) 2203‐2090 e‐mail: [email protected] Rio de Janeiro, March 8, 2013 Excellency: On behalf of the Inter-American Juridical Committee I am pleased to forward to the Permanent Council of the Organization of American States, through your good offices, the report on “Model Legislation on protection of cultural property in the event of armed conflict,” adopted by the Inter- American Juridical Committee at its session in March 2013 pursuant to a General Assembly mandate requesting the Committee to “propose model laws to support the efforts made by member states to fulfill obligations under international humanitarian law treaties, with an emphasis on protection of cultural property in the event of armed conflict.” Accept, Excellency, the renewed assurances of my highest consideration. João Clemente Baena Soares Chair Inter-American Juridical Committee To His Excellency Ambassador Arturo Vallarino Permanent Representative of Panama to the Organization of American States Chair of the Permanent Council 82nd REGULAR SESSION OEA/Ser.Q March 11 – 15, 2013 CJI/doc.403/12 rev.5 Rio de Janeiro, Brazil March 15, 2013 Original: Spanish MODEL LEGISLATION ON PROTECTION OF CULTURAL PROPERTY IN THE EVENT OF ARMED CONFLICT (Presented by Dr. -

Gulf States Accused of Co-Ordinated Crackdown on Dissent | World

Gulf states accused of co-ordinated crackdown on dissent UAE's refusal to grant entry to an LSE academic and two Bahraini journalists may stem from security deal agreed last year Ian Black, Middle East editor guardian.co.uk, Tuesday 26 February 2013 17.16 GMT Saudi Arabia led a GCC intervention force in the suppression of protests in Bahrain in March 2011, with a UAE contingent also taking part. Photograph: AFP/Getty Images Nervous Gulf states appear to be co-ordinating a crackdown on critics in the media and academic world as well as on political activists who challenge the status quo and protest about human rights abuses. Two leading Bahraini journalists were blocked from entering the United Arab Emirates on Monday for unspecified reasons, just days after the UAE refused entry to Kristian Ulrichsen, of the London School of Economics, who was scheduled to speak about Bahrain at a conference on the Arab spring, which has unsettled all the region's conservative monarchies. Mansour al-Jamri, editor of the Bahraini newspaper al-Wasat, was refused entry at Dubai international airport along with his wife, Reem Khalifa, an Associated Press correspondent. Jamri had been due to attend a conference on newspapers but believes the ban stems from a security deal agreed by the six Gulf Co-operation Council (GCC) members last year. "The ban clearly has nothing to do with the conference," he told the Guardian . "But we were told it was a decision from the top." The contents of the pact remain secret but it includes a shared database. -

Weaponizing Tear Gas: Bahrain’S Unprecedented Use of Toxic Chemical Agents Against Civilians

Physicians for Human Rights Weaponizing Tear Gas: Bahrain’s Unprecedented Use of Toxic Chemical Agents Against Civilians August 2012 physiciansforhumanrights.org About Physicians for Human Rights Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) uses medicine and science to investigate and expose human rights violations. We work to prevent rights abuses by seeking justice and holding offenders accountable. Since 1986, PHR has conducted investigations in more than 40 countries, including on: 1987 — Use of toxic chemical agents in South Korea 1988 — Iraq’s use of chemical weapons against Kurds 1988 — Use of toxic chemical agents in West Bank and the Gaza Strip 1989 — Use of chemical warfare agents in Soviet Georgia 1996 — Exhumation of mass graves in the Balkans 1996 — Critical forensic evidence of genocide in Rwanda 1999 — Drafting the UN-endorsed guidelines for documentation of torture 2004 — Documentation of the genocide in Darfur 2008 — US complicity of torture in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Guantánamo Bay 2010 — Human experimentation by CIA medical personnel on prisoners in violation of the Nuremberg Code 2011 — Violations of medical neutrality in times of armed conflict and civil unrest during the Arab Spring ... 2 Arrow Street | Suite 301 1156 15th Street, NW | Suite 1001 Cambridge, MA 02138 USA Washington, DC 20005 USA +1 617 301 4200 +1 202 728 5335 physiciansforhumanrights.org ©2012, Physicians for Human Rights. All rights reserved. ISBN: 1-879707-68-3 Library of Congress Control Number: 2012945532 Cover photo: Bahraini anti-riot police fire tear gas grenades at peaceful and unarmed civilians protesters, including a Shi’a cleric, in June 2012. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QxauI5hdjqk. -

ICRC Statement -- Status of the Protocols Additional

United Nations General Assembly 73rd Session Sixth Committee General debate on the Status of the Protocols additional to the Geneva Conventions of 1949 and relating to the protection of victims of armed conflicts [Agenda item 83, to be considered in October 2018] Statement by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) October 2018 Mr / Madam Chair, On the occasion of the 40th anniversary of the Additional Protocols of 1977, the ICRC took several steps to promote the universalization and implementation of these instruments. Its initiatives included the publication of a policy paper on the impact and practical relevance of the Additional Protocols, raising the question of accession in its dialogue with States, and highlighting the relevance of these instruments through national and regional events. Among other steps taken, the ICRC wrote to States not yet party to the Additional Protocols encouraging them to adhere to these instruments. We reiterate our call to States that have not yet done so, to ratify the Additional Protocols and other key instruments of IHL. At the time of writing, 174 States are party to Additional Protocol I and 168 States are party to Additional Protocol II. Since our last intervention, Burkina Faso and Madagascar became States number 73 and 74 to ratify Additional Protocol III. In April 2018, Palestine made a declaration pursuant to Article 90 of Additional Protocol I making it the 77th State to accept the competence of the International Humanitarian Fact-Finding Commission. We welcome the fact that the number of States party to this and other key instruments of IHL has continued to grow. -

Marking the 40Th Anniversary of the Additional Protocols to The

Title: Marking the 40th anniversary of the Additional Protocols to the Geneva Conventions: The impact and practical relevance of the Additional Protocols – a focus on urban warfare and humanitarian relief and access Organizers: ICRC Co-sponsors: Argentina, France, Senegal Time and Date: Thursday 22 June 2017 13:15 to 14:45 Room XXII, Palais des Nations, Geneva This is one of the side-events to be convened during the ECOSOC Humanitarian Affairs Segment, in keeping with this year’s theme: Restoring Humanity and Leaving No One Behind: Working together to reduce people's humanitarian need, risk and vulnerability. Background and objectives On 8 June 1977, States parties to the Geneva Conventions adopted Additional Protocols I and II - a landmark in the development of international humanitarian law (IHL). The Protocols codified basic principles and rules of IHL. They also developed new rules to reflect the changing face of modern conflicts. After the Second World War, non-international armed conflicts far outnumbered international armed conflicts, and civilians were left largely beyond the protection of the 1949 Geneva Conventions.1 There was also a proliferation of asymmetric conflicts, with guerrilla fighters adopting unconventional tactics as they faced well-organized and well- equipped armies. The Cold War arms race and the development of new weapons technologies brought new realities to the battlefield, such as aerial weapons and rockets. They allowed strikes to take place virtually anywhere and were subject to few specific regulations. Given these experiences and the changing face of modern armed conflicts, the existing principles of IHL needed to be reaffirmed and clarified, and essential rules on the conduct of hostilities needed to be codified and developed further.