Coastal Panicgrass (Panicum Amarum Elliot Var. Amarulum) Plant Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Improved Conservation Plant Materials Released by NRCS and Cooperators Through December 2014

Natural Resources Conservation Service Improved Conservation Plant Materials Released by Plant Materials Program NRCS and Cooperators through December 2014 Page intentionally left blank. Natural Resources Conservation Service Plant Materials Program Improved Conservation Plant Materials Released by NRCS and Cooperators Through December 2014 Norman A. Berg Plant Materials Center 8791 Beaver Dam Road Building 509, BARC-East Beltsville, Maryland 20705 U.S.A. Phone: (301) 504-8175 prepared by: Julie A. DePue Data Manager/Secretary [email protected] John M. Englert Plant Materials Program Leader [email protected] January 2015 Visit our Website: http://Plant-Materials.nrcs.usda.gov TABLE OF CONTENTS Topics Page Introduction ...........................................................................................................................................................1 Types of Plant Materials Releases ........................................................................................................................2 Sources of Plant Materials ....................................................................................................................................3 NRCS Conservation Plants Released in 2013 and 2014 .......................................................................................4 Complete Listing of Conservation Plants Released through December 2014 ......................................................6 Grasses ......................................................................................................................................................8 -

Heathland 700 the Park & Poor's Allotment Species List

The Park & Poor's Allotment Bioblitz 25th - 26th July 2015 Common Name Scientific Name [if known] Site recorded Fungus Xylaria polymorpha Dead Man's Fingers Both Amanita excelsa var. excelsa Grey Spotted Amanita Poor's Allotment Panaeolus sp. Poor's Allotment Phallus impudicus var. impudicus Stinkhorn The Park Mosses Sphagnum denticulatum Cow-horn Bog-moss Both Sphagnum fimbriatum Fringed Bog-moss The Park Sphagnum papillosum Papillose Bog-moss The Park Sphagnum squarrosum Spiky Bog-moss The Park Sphagnum palustre Blunt-leaved Bog-moss Poor's Allotment Atrichum undulatum Common Smoothcap Both Polytrichum commune Common Haircap The Park Polytrichum formosum Bank Haircap Both Polytrichum juniperinum Juniper Haircap The Park Tetraphis pellucida Pellucid Four-tooth Moss The Park Schistidium crassipilum Thickpoint Grimmia Poor's Allotment Fissidens taxifolius Common Pocket-moss The Park Ceratodon purpureus Redshank The Park Dicranoweisia cirrata Common Pincushion Both Dicranella heteromalla Silky Forklet-moss Both Dicranella varia Variable Forklet-moss The Park Dicranum scoparium Broom Fork-moss Both Campylopus flexuosus Rusty Swan-neck Moss Poor's Allotment Campylopus introflexus Heath Star Moss Both Campylopus pyriformis Dwarf Swan-neck Moss The Park Bryoerythrophyllum Red Beard-moss Poor's Allotment Barbula convoluta Lesser Bird's-claw Beard-moss The Park Didymodon fallax Fallacious Beard-moss The Park Didymodon insulanus Cylindric Beard-moss Poor's Allotment Zygodon conoideus Lesser Yoke-moss The Park Zygodon viridissimus Green Yoke-moss -

Jason Giessow Testimony

Raszka Shelley From: Gallagher Chuck Sent: Friday, March 27, 2015 9:50 AM To: Raszka Shelley Subject: FW: testimony on HB 2183 Attachments: Cal-IPCNews_Winter2015.pdf From: Jason Giessow [ mailto:[email protected] ] Sent: Friday, March 27, 2015 9:49 AM To: Gallagher Chuck Subject: testimony on HB 2183 Hi Chuck- I was the primary author on this Impact Assessment for CA. It is posted at this web site: http://www.cal-ipc.org/ip/research/arundo/index.php Basically- no one should be growing Arundo, it is destroying riverine systems in CA and Texas. There are entire conferences about how to control Arundo and tamarisk (the Deadly Duo). In the report is a CBA for coastal watersheds in CA and estimates $380 million dollars in damage . It destroys habitat- but also severely impacts flooding, fire, and water (the impact report has a chapter on each). That is why folks from both sides of the isle work on eradicating this plant. Planting it for commercial use is exceedingly dangerous, should be banned, or bonded at very high levels. CA has spent about $100 million dollars dealing with Arundo and its impacts (mostly state bond funds dealing with water: conservation, conveyance, and improvement). New state funding (Proposition 1) for water conservation and river conveyance will likely increase state funding for Arundo control to over $200 million dollars. Don’t let Oregon follow this trajectory. This recent article (attached- page 10) on the Salinas River Arundo program is one example of the impacts caused by Arundo, the complicated regulatory approval required to work on the issue, the high cost of the program, and most important- the farmers and landowners who pay the price for the impacts caused by Arundo (flooding, less water, fire, etc….). -

NJ Native Plants - USDA

NJ Native Plants - USDA Scientific Name Common Name N/I Family Category National Wetland Indicator Status Thermopsis villosa Aaron's rod N Fabaceae Dicot Rubus depavitus Aberdeen dewberry N Rosaceae Dicot Artemisia absinthium absinthium I Asteraceae Dicot Aplectrum hyemale Adam and Eve N Orchidaceae Monocot FAC-, FACW Yucca filamentosa Adam's needle N Agavaceae Monocot Gentianella quinquefolia agueweed N Gentianaceae Dicot FAC, FACW- Rhamnus alnifolia alderleaf buckthorn N Rhamnaceae Dicot FACU, OBL Medicago sativa alfalfa I Fabaceae Dicot Ranunculus cymbalaria alkali buttercup N Ranunculaceae Dicot OBL Rubus allegheniensis Allegheny blackberry N Rosaceae Dicot UPL, FACW Hieracium paniculatum Allegheny hawkweed N Asteraceae Dicot Mimulus ringens Allegheny monkeyflower N Scrophulariaceae Dicot OBL Ranunculus allegheniensis Allegheny Mountain buttercup N Ranunculaceae Dicot FACU, FAC Prunus alleghaniensis Allegheny plum N Rosaceae Dicot UPL, NI Amelanchier laevis Allegheny serviceberry N Rosaceae Dicot Hylotelephium telephioides Allegheny stonecrop N Crassulaceae Dicot Adlumia fungosa allegheny vine N Fumariaceae Dicot Centaurea transalpina alpine knapweed N Asteraceae Dicot Potamogeton alpinus alpine pondweed N Potamogetonaceae Monocot OBL Viola labradorica alpine violet N Violaceae Dicot FAC Trifolium hybridum alsike clover I Fabaceae Dicot FACU-, FAC Cornus alternifolia alternateleaf dogwood N Cornaceae Dicot Strophostyles helvola amberique-bean N Fabaceae Dicot Puccinellia americana American alkaligrass N Poaceae Monocot Heuchera americana -

Ammophila Poster

Genetic Structure of Natural and Restored Populations of Ammophila breviligulata By Eileen Sirkin, Susanne Masi, and Jeremie Fant. Ammophila breviligulata at Ammophila breviligulata from Chicago Botanic Garden, Glencoe IL, 60022 Illinois Beach State Park Michigan side of the lake Dune Restorations: Importance of Beachgrass Chicago Lakefront Collection Area Illinois Beach State Park Distribution of Clones in Illinois Beachgrass samples were collected at: American Beachgrass, Ammophila breviligulata, is one of the first Illinois Beach State Park (natural) A comparison of the distribution of individual clones showed that plants to colonize sandy shores beyond the water’s edge. It functions Kathy Osterman Beach (natural) many of the spontaneous beaches shared clones, suggesting that to create and stabilize the beach and dune system, because of its Montrose Beach (natural/augmented) these had spread throughout the region. The nursery stock was tolerance of unstable beachfront conditions and ability to spread South Shore Beach (restored) comprised of a single clone, which was also identified on two of the utilizing underground rhizomes. The importance of Beachgrass for Questions Rainbow Beach (natural) planted beaches, suggesting that this supplier might have been the creating and stabilizing dunes has been recognized since at least 1958 source of the planted material. This clone was also found in many (Olson, 1958). In our own Lake Michigan shoreline study area, This genetic analysis focused on answering of the spontaneous populations, suggesting it is of local origin Beachgrass has been introduced at several Chicago lakefront sites, as two questions. First, what is the natural (assuming it was not introduced by planting). South Shore, a well as in surrounding areas. -

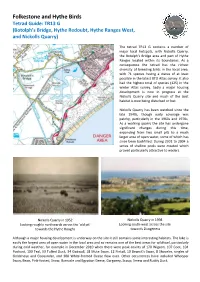

Botolph's Bridge, Hythe Redoubt, Hythe Ranges West And

Folkestone and Hythe Birds Tetrad Guide: TR13 G (Botolph’s Bridge, Hythe Redoubt, Hythe Ranges West, and Nickolls Quarry) The tetrad TR13 G contains a number of major local hotspots, with Nickolls Quarry, the Botolph’s Bridge area and part of Hythe Ranges located within its boundaries. As a consequence the tetrad has the richest diversity of breeding birds in the local area, with 71 species having a status of at least possible in the latest BTO Atlas survey. It also had the highest total of species (125) in the winter Atlas survey. Sadly a major housing development is now in progress at the Nickolls Quarry site and much of the best habitat is now being disturbed or lost. Nickolls Quarry has been watched since the late 1940s, though early coverage was patchy, particularly in the 1960s and 1970s. As a working quarry the site has undergone significant changes during this time, expanding from two small pits to a much larger area of open water, some of which has since been backfilled. During 2001 to 2004 a series of shallow pools were created which proved particularly attractive to waders. Nickolls Quarry in 1952 Nickolls Quarry in 1998 Looking roughly northwards across the 'old pit' Looking south-west across the site towards the Hythe Roughs towards Dungeness Although a major housing development is underway on the site it still contains some interesting habitats. The lake is easily the largest area of open water in the local area and so remains one of the best areas for wildfowl, particularly during cold weather, for example in December 2010 when there were peak counts of 170 Wigeon, 107 Coot, 104 Pochard, 100 Teal, 53 Tufted Duck, 34 Gadwall, 18 Mute Swan, 12 Pintail, 10 Bewick’s Swan, 8 Shoveler, singles of Goldeneye and Goosander, and 300 White-fronted Geese flew over. -

A Preliminary List of the Vascular Plants and Wildlife at the Village Of

A Floristic Evaluation of the Natural Plant Communities and Grounds Occurring at The Key West Botanical Garden, Stock Island, Monroe County, Florida Steven W. Woodmansee [email protected] January 20, 2006 Submitted by The Institute for Regional Conservation 22601 S.W. 152 Avenue, Miami, Florida 33170 George D. Gann, Executive Director Submitted to CarolAnn Sharkey Key West Botanical Garden 5210 College Road Key West, Florida 33040 and Kate Marks Heritage Preservation 1012 14th Street, NW, Suite 1200 Washington DC 20005 Introduction The Key West Botanical Garden (KWBG) is located at 5210 College Road on Stock Island, Monroe County, Florida. It is a 7.5 acre conservation area, owned by the City of Key West. The KWBG requested that The Institute for Regional Conservation (IRC) conduct a floristic evaluation of its natural areas and grounds and to provide recommendations. Study Design On August 9-10, 2005 an inventory of all vascular plants was conducted at the KWBG. All areas of the KWBG were visited, including the newly acquired property to the south. Special attention was paid toward the remnant natural habitats. A preliminary plant list was established. Plant taxonomy generally follows Wunderlin (1998) and Bailey et al. (1976). Results Five distinct habitats were recorded for the KWBG. Two of which are human altered and are artificial being classified as developed upland and modified wetland. In addition, three natural habitats are found at the KWBG. They are coastal berm (here termed buttonwood hammock), rockland hammock, and tidal swamp habitats. Developed and Modified Habitats Garden and Developed Upland Areas The developed upland portions include the maintained garden areas as well as the cleared parking areas, building edges, and paths. -

Long-Term Effects of Planted Ammophila Breviligulata on North Beach Dune

Long-term Effects of Planted Ammophila breviligulata on North Beach Dune by Jacob T. Swineford, Grant Hoekwater, Issac J. Jacques, Manny L. Schrotenboer, and Matt Wierenga FYRES: Dunes Research Report # 16 May 2015 Department of Geology, Geography and Environmental Studies Calvin College Grand Rapids, Michigan ABSTRACT Ammophila breviligulata is a beach grass commonly planted for dune management because of its burial tolerance and effectiveness in sand stabilization. The long term effect of planted beachgrass is not fully understood. This study investigated the vegetation health, distribution, and density of planted A. breviligulata in relation to the characteristics of a Lake Michigan coastal dune site. The study location is North Beach dune, which in 2004 was moving towards the only access road for many shoreline homes. To stabilize the dune, Ottawa County Park staff and volunteers have been planting A. breviligulata periodically over the past ten years. The investigation included comparing photographs from 2004 to 2014 and using GPS to map vegetated areas. The study area was divided into 9 sections and randomly-selected quadrats were used to measure plant health, maximum height, and density. Photographic comparisons show that the planted beach grass has spread across much of the windward slope of the dune. Grass near sand fences was taller and healthier than grasses in transition areas between bare sand and full vegetation. Areas with steeper slopes had generally taller, healthier plants than areas with gentle slopes. The results suggest that 5-10 years after being planted, A. breviligulata was moderately healthy and offering greater protection to the dune surface. 1 INTRODUCTION Ammophila breviligulata (American beach grass) is a commonly used beachgrass for management and stabilization purposes because of its tolerance for burial (Figure 1). -

Evaluating the Effects of Mechanical and Manual

EVALUATING THE EFFECTS OF MECHANICAL AND MANUAL REMOVAL OF Ammophila arenaria WITHIN COASTAL DUNES OF HUMBOLDT COUNTY ____________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Chico ____________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Biological Sciences ____________ by Ayla Joy Mills Spring 2015 EVALUATING THE EFFECTS OF MECHANICAL AND MANUAL REMOVAL OF Ammophila arenaria WITHIN COASTAL DUNES OF HUMBOLDT COUNTY A Thesis by Ayla Joy Mills Spring 2015 APPROVED BY THE DEAN OF GRADUATE STUDIES AND VICE PROVOST FOR RESEARCH: _________________________________ Eun K. Park, Ph.D. APPROVED BY THE GRADUATE ADVISORY COMMITTEE: ______________________________ _________________________________ Guy Q. King, Ph.D. Kristina Schierenbeck, Ph.D., Chair Graduate Coordinator _________________________________ Colleen Hatfield, Ph.D. ______________________________ _________________________________ Guy Q. King, Ph.D. Adrienne Edwards, Ph.D. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my advisor and committee chair Kristina Schierenbeck. She has given me great advice and assistance throughout the process. I would also like to thank my knowledgeable committee members Colleen Hatfield and Adrienne Edwards. A special thanks to Amber Transou and California State Park’s North Coast Redwood District for providing me with guidance, funding, equipment, and for making this project possible. I’d like to thank my wonderful husband Jason who helped me set up my plots and collect data, even when it was cold and raining. I couldn’t have done it without you. I would like to thank my Mom who helped me financially and emotionally make it through graduate school. I would also like to thank my best friend Krystal Godfrey for always being there to listen to me vent and also for helping collect data. -

Can the Riparian Invader, Arundo Donax, Benefit

DOI: 10.1111/wre.12036 Can the riparian invader, Arundo donax, benefit from clonal integration? L KUI*†, F LI*, G MOORE* & J WEST* *Department of Ecosystem Science and Management, Texas A & M University, College Station, TX, USA, and †College of Environmental Science and Forestry, State University of New York, Syracuse, NY, USA Received 30 April 2013 Revised version accepted 3 June 2013 Subject Editor: Francesco Tei, Perugia, Italy objective was to determine whether clonal integration Summary enhanced growth and survival of A. donax ramets. We Resource sharing through rhizomes of clonal plants compared growth-related responses in paired 1 m2 supplements locally available nutrients to enhance plots with severed and intact rhizomes. In the first recruitment and growth in resource-limited environ- 19 days, rhizome severing nearly doubled ramet ments. We investigated whether Arundo donax,an density, while by 77 days, the intact rhizomes pro- invasive clonal plant, can benefit from clonal integra- duced 67% taller stems with 49% greater diameter tion. Sharing resources between ramets can facilitate and showed higher survival rate after flooding. This resprouting from mowing, fire and herbicide treat- study provides initial evidence that physiological inte- ments, but it is unknown whether clonal integration gration could be an important mechanism in A. donax, contributes to A. donax invasion success. Our first which can enhance its competitive abilities, accelerate objective was to determine whether A. donax rhizomes rates of encroachment and strengthen its capability to transported water between ramets. Hydrogen isotopic– recolonise disturbed areas. Our results highlight an enriched water was applied on three 1 m diameter important consideration of clonal invasive species in areas, and rhizome and soil samples were collected weed management. -

Addendum to the Guide to the Natural Communities of the Delaware Estuary

ADDENDUM TO THE UIDE TO THE ATURAL OMMUNITIES G N C OF THE DELAWARE ESTUARY SEPTEMBER0 2009 Citation: Largay, E. and L. Sneddon. 2009. Addendum to the Guide to the Ecological Systems and Vegetation Communities of the Delaware Estuary. NatureServe. Arlington, Virginia. Partnership for the Delaware Estuary, Report #09-XX. 112 pp. PDE Report No. 09-XX Copyright © 2009 NatureServe COVER PHOTOS Top L: Overwash Dunes, photo from Delaware Natural Heritage Program Top R: Coastal Plain Muck Pondshore, photo by Kathleen Strakosch Walz, New Jersey Natural Heritage Program Bottom L: Dry Oak Hickory Forest, photo by Tony Davis, Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program Bottom R: Inland Dune and Ridge Forest/Woodland, Kathleen Strakosch Walz, New Jersey Natural Heritage Program ADDENDUM TO THE GUIDE TO THE NATURAL COMMUNITIES OF THE DELAWARE ESTUARY Ery Largay Lesley Sneddon September 2009 Acknowledgements: This work was made possible through funding from the Delaware Estuary Program (EPA 320 Funding). Kristin Snow and Mary Russo from NatureServe provided essential data management services to develop this report and report format. Robert Coxe and Bill McAvoy from the Delaware Natural Heritage Program, Kathleen Strakosch Walz from the New Jersey Natural Heritage Program, Tony Davis from the Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program, Linda Kelly and Karl Anderson, independent botanists, provided ecological expertise, energy and insight. Mark Anderson and Charles Ferree from The Nature Conservancy developed ecological systems maps to accompany this work. Danielle Kreeger, Laura Whalen, and Martha-Maxwell Doyle from the Partnership for the Delaware Estuary provided support and guidance throughout this project. We thank everyone who helped us with this effort. -

Acadian-Appalachian Alpine Tundra

Acadian-Appalachian Alpine Tundra Macrogroup: Alpine yourStateNatural Heritage Ecologist for more information about this habitat. This is modeledmap a distributiononbased current and is data nota substitute for field inventory. based Contact © Josh Royte (The Nature Conservancy, Maine) Description: A sparsely vegetated system near or above treeline in the Northern Appalachian Mountains, dominated by lichens, dwarf-shrubland, and sedges. At the highest elevations, the dominant plants are dwarf heaths such as alpine bilberry and cushion-plants such as diapensia. Bigelow’s sedge is characteristic. Wetland depressions, such as small alpine bogs and rare sloping fens, may be found within the surrounding upland matrix. In the lower subalpine zone, deciduous shrubs such as nannyberry provide cover in somewhat protected areas; dwarf heaths including crowberry, Labrador tea, sheep laurel, and lowbush blueberry, are typical. Nearer treeline, spruce and fir that State Distribution: ME, NH, NY, VT have become progressively more stunted as exposure increases may form nearly impenetrable krummholz. Total Habitat Acreage: 8,185 Ecological Setting and Natural Processes: Percent Conserved: 98.1% High winds, snow and ice, cloud-cover fog, and intense State State GAP 1&2 GAP 3 Unsecured summer sun exposure are common and control ecosystem State Habitat % Acreage (acres) (acres) (acres) dynamics. Found mostly above 4000' in the northern part of NH 51% 4,160 4,126 0 34 our region, alpine tundra may also occur in small patches on ME 44% 3,624 2,510 1,082 33 lower ridgelines and summits and at lower elevations near the Atlantic coast. NY 3% 285 194 0 91 VT 1% 115 115 0 0 Similar Habitat Types: Acadian-Appalachian Montane Spruce-Fir-Hardwood Forests typically occur downslope.