Organizational Conflict: Strategy, Leadership, Resolution Framework, and Managerial Implications Ashford Chea Stillman College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Workplace Conflict and How Businesses Can Harness It to Thrive

JULY 2008 JULY WORKPLACE CONFLICT AND HOW BUSINESSES CAN Maximizing People Performance HARNESS IT TO THRIVE United States Asia Pacific CPP, Inc. CPP Asia Pacific (CPP-AP) 369 Royal Parade Fl 7 Corporate Headquarters P.O. Box 810 1055 Joaquin Rd Fl 2 Parkville, Victoria 3052 Mountain View, CA , 94043 Tel: 650.969.8901 Australia Fax: 650.969.8608 Tel: 61.3.9342.1300 REPORT HUMAN CAPITAL Website: www.cpp.com Email: [email protected] DC Office Beijing 1660 L St NW Suite 601 Tel: 86.10.6463.0800 Washington DC 20036 Email: [email protected] Tel: 202.887.8420 Fax: 202.8878433 Hong Kong Website: www.cpp.com Tel: 852.2817.6807 Email: [email protected] Research Division 4801 Highway 61 Suite 206 India White Bear Lake, MN 55110 Tel: 91.44.4201.9547 Email: [email protected] Customer Service Product orders, inquiries, and support Malaysia Toll free: 800.624.1765 Tel: 65.6333.8481 CPP GLOBAL Tel: 650.969.8901 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Shanghai Professional Services Tel: 86.21.5386.5508 Consulting services and inquiries Email: [email protected] Toll free: 800.624.1765 Tel: 650.969.8901 Singapore Website: www.cpp.com/contactps Tel: 65.6333.8481 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Mexico CPP, Inc Toll free: 800.624.1765 ext 296 Email: [email protected] Maximizing People Performance WORKPLACE CONFLICT AND HOW BUSINESSES CAN HARNESS IT TO THRIVE by Jeff Hayes, CEO, CPP, Inc. FOREWORD OPP® is one of Europe’s leading business psychology firms. -

Constructively Managing Conflicts in Organizations

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/261181240 Constructively Managing Conflicts in Organizations Article · March 2014 DOI: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091306 CITATIONS READS 20 745 3 authors, including: Dean Tjosvold Nancy Chen Yi-Feng Lingnan University Lingnan University 263 PUBLICATIONS 6,132 CITATIONS 22 PUBLICATIONS 473 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Available from: Dean Tjosvold Retrieved on: 15 April 2016 Constructively Managing Conflicts in Organizations Dean Tjosvold, Alfred S.H. Wong, and Nancy Yi Feng Chen Department of Management, Lingnan University, Hong Kong; email: [email protected] Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2014. Keywords 1:545–68 negotiations, teamwork, constructive conflict, open-minded, The Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior is online at mutual benefit, cooperation orgpsych.annualreviews.org Abstract This article’s doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091306 Researchers have used various concepts to understand the conditions Copyright © 2014 by Annual Reviews. and dynamics by which conflict can be managed constructively. This All rights reserved review proposes that the variety of terms obscures consistent findings by ${individualUser.displayName} on 03/30/14. For personal use only. that open-minded discussions in which protagonists freely express their own views, listen and understand opposing ones, and then in- tegrate them promote constructive conflict. Studies from several tra- ditions also suggest that mutual benefit relationships are critical Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 2014.1:545-568. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org antecedents for open-minded discussion. This integration of research findings identifies the skills and relationships that can help managers and employees deal with their increasingly complex conflicts. -

Organizational Conflicts Perceived by Marketing Executives

EJBO Electronic Journal of Business Ethics and Organization Studies Vol. 10, No. 1 (2005) Organizational Conflicts Perceived by Marketing Executives By: Ana Akemi Ikeda Introduction and Stringfellow (1998) and Song, Xie [email protected] and Dyer (2000) analyze conflict man- Tânia Modesto Veludo-de-Oliveira The potential for conflict exists in agement comparing Japan, Hong Kong, [email protected] every organization. Despite that, little United States and Great Britain during Marcos Cortez Campomar thought is given to organizational behav- new products launching, as well as the in- [email protected] ior analysis, especially in marketing. This tegration of marketing with Research and complex phenomenon brings implica- Development (R&D) and Production. tions to social life and its understanding Jung’s (2003) research, in turn, analyzes Abstract offers insights into a more effective organ- the effects of the culture of an organiza- This article discusses the conflict izational management. The organization tion in conflict resolution in marketing. is a rich arena for the study of conflicts Apparently, what is more emphasized in phenomenon and examines some because there are highly dependent situ- marketing literature is conflicts between strategies to overcome it. Concepts ations that involve authority, hierarchical distribution channels as shown in the are discussed and employed for the power and groups (Tjosvold, 1998). works of Mallen (1963), Assael (1968), development of an exploratory field Conflicts can be discussed in a Rosson and Ford (1980), Lederhaus survey carried out with Brazilian number of different aspects. Some pre- (1984), Eliashberg and Michie (1984), marketing executives. Results show vious works refer to the human aspect Gaski (1984), Hunt, Ray and Wood of conflict, stressing that conflict doesn’t (1985), Brown, Lusch and Smith (1984) that conflicts are more felt in the exist with lack of emotion (Bodtker and and Dant and Schul (1992). -

Unpacking the Meaning of Conflict in Organizational Conflict Research

Unpacking the Meaning of Conflict in Organizational Conflict Research Mikkelsen, Elisabeth Naima; Clegg, Steward Document Version Accepted author manuscript Published in: Negotiation and Conflict Management Research DOI: 10.1111/ncmr.12127 Publication date: 2018 License Unspecified Citation for published version (APA): Mikkelsen, E. N., & Clegg, S. (2018). Unpacking the Meaning of Conflict in Organizational Conflict Research. Negotiation and Conflict Management Research, 11(3), 185-203. https://doi.org/10.1111/ncmr.12127 Link to publication in CBS Research Portal General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us ([email protected]) providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 29. Sep. 2021 Unpacking the Meaning of Conflict in Organizational Conflict Research Elisabeth Naima Mikkelsen and Steward Clegg Journal article (Accepted manuscript*) Please cite this article as: Mikkelsen, E. N., & Clegg, S. (2018). Unpacking the Meaning of Conflict in Organizational Conflict Research. Negotiation and Conflict Management Research, 11(3), 185-203. https://doi.org/10.1111/ncmr.12127 This is the peer reviewed version of the article, which has been published in final form at DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/ncmr.12127 This article may be used for non-commercial purposes in accordance with Wiley Terms and Conditions for Self-Archiving * This version of the article has been accepted for publication and undergone full peer review but has not been through the copyediting, typesetting, pagination and proofreading process, which may lead to differences between this version and the publisher’s final version AKA Version of Record. -

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Relationship Between Organizational Culture and Conflict Management Styles of Managers and Experts

1056 Advances in Environmental Biology, 6(3): 1056-1062, 2012 ISSN 1995-0756 This is a refereed journal and all articles are professionally screened and reviewed ORIGINAL ARTICLE Relationship Between Organizational Culture And Conflict Management Styles Of Managers And Experts Shaghayegh Kiani Mehr Department of physical Education, Ayatollah Amoli Branch, Islamic Azad University, Amol, Iran Shaghayegh Kiani Mehr: Relationship Between Organizational Culture And Conflict Management Styles Of Managers And Experts ABSTRACT Today cultural clashes in any international project organization have led to an increased emphasis on preparedness on potential conflicts residing in cross-cultural collaboration. Cultural differences often result in varying degrees of conflict and require careful consideration. So the Objective of this research is the relationship between organizational culture and conflict management styles. The method of this study is descriptive – correlational. The statistical population consisted the staffs of physical education departments of Mazandaran province in Iran, including 151 that replied two questionnaires of OCAQ (Marshal Sashkin) and OCCI (Putnam & Wilson). The reliabilities of the questionnaires were estimated with Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. Organizational culture is 0.76 and conflict management styles are 0.87. Pearson statistical methods were used, there are not relationship between organizational culture with four of Conflict management styles (Collaboration, Compromise, Avoidance, Accommodation), only there is an inverse relationship between organizational culture with domination style of conflict management. Key words: Organizational culture, conflict management, styles, managers, experts. Introduction misunderstanding lie in information acquisition and comprehension would surely sour the chance of Today’s trend of globalization brings up many making wise decisions. In consequence, conventional chances of working together with people from organizational designs that focus on “exception different places of the world. -

Interpersonal Conflict: a Substantial Factor to Organizational Failure

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences May 2013, Vol. 3, No. 5 ISSN: 2222-6990 Interpersonal Conflict: A Substantial Factor to Organizational Failure Malikeh Beheshtifar Management Department, Rafsanjan Branch, Islamic AZAD University, Iran Elham Zare Management Department, Rafsanjan Branch, Islamic AZAD University, Iran Abstract Interpersonal conflict is conflict that occurs between two or more individuals that work together in groups or teams. This is a conflict that occurs between two or more individuals. Many individual differences lead to interpersonal conflict, including personalities, culture, attitudes, values, perceptions, and the other differences. Conflict arises due to a variety of factors. Individual differences in goals, expectations, values, proposed courses of action, and suggestions about how to best handle a situation are unavoidable. Moreover, identifying the factors which cause conflict in any organization is considered the main stage in the process of conflict management. The management of interpersonal conflict involves changes in the attitudes, behavior, and organization structure, so that the organizational members can work with each other effectively for attaining their individual and/or joint goals. The management of interpersonal conflict essentially involves teaching organizational members the styles of handling interpersonal conflict to deal with different situations effectively and setting up appropriate mechanisms so that unresolved issues are dealt with properly. The researcher recommends other scholars to identify the other factors of organizational conflict, such as identifying a list of factors causing intrapersonal conflict. Keywords: conflict, interpersonal conflict, sources of conflict Introduction The conflict comprises a series of human affective states such as: anxiety, hostility, resistance, open aggression, as well as the types of opposition and antagonistic interaction, including competition. -

Conflict Management and Organizational Performance: a Case Study of Askari Bank Ltd

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Institute for Science, Technology and Education (IISTE): E-Journals Research Journal of Finance and Accounting www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1697 (Paper) ISSN 2222-2847 (Online) Vol.6, No.11, 2015 Conflict Management and Organizational Performance: A Case Study of Askari Bank Ltd. Abdul Ghafoor Awan Dean, Faculty of Management and Social Sciences, Institute of Southern Punjab, Pakistan [email protected] Sehar Saeed MS Research Scholar Department of Business Administration, Institute of Southern Punjab, Pakistan [email protected] Abstract In a society where people with a diverse interests, views, and values coexist, differences between such individuals and groups are to be expected. The objective of this research study is to look at conflict situations and its causes, as well as possible solution of improve working environment in an Organization. Our study shows that Conflict stems from incompatibility of goals and interest and if it continued it will destroy the Organization. Conflict affects the Organization in several ways such as decreased employee satisfaction, insubordination, decreased productivity, economic loss, fragmentation, and poor performance. A formal questionnaire was constructed and survey method was used to collect data from a target group of respondents. Descriptive analytical techniques such as frequency, percentage, mean, standard deviation & variance and factor analysis were applied to analyze and interpret the data. Ratio Analysis is used to analyze Askari Bank’s performance. The major findings are that Education does not have any effect on the opinion of respondents on Conflict Management Strategies. -

Western ERP Roll-Out in China: Insights from Two Case Studies and Preliminary Guidelines

Western ERP Roll-out in China: Insights from Two Case Studies and Preliminary Guidelines Paola Cocca a, Filippo Marciano b, Elena Stefana c and Maurizio Pedersoli Department of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering, University of Brescia, Via Branze 38, Brescia, Italy Keywords: Enterprise Resource Planning, Multisite ERP Implementation, China, Chinese Culture, Case Study, Roll-out, Western ERP. Abstract: China is one of the countries with the highest failure rate of implementation of foreign – western - ERP systems. Western companies encounter difficulties in their roll-out projects in China mainly for cultural issues. Based on the insights from two case studies, this paper aims to provide a preliminary analysis of the main criticalities of western ERP roll-outs in China and suggest guidelines to increase their success rate. 1 INTRODUCTION Having become one of the greatest economy in the world, China and its market are of great interest for An Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) system is western enterprises, that often decide to establish defined as “a set of business applications or modules, there a subsidiary or to make a joint venture with a which links various business units of an organisation Chinese company. These enterprises adopt ERP such as financial, accounting, manufacturing and systems of western vendors and thus may encounter human resources, into a tightly integrated single difficulties in their roll-out projects in China. A roll- system with a common platform for flow of out is an expansion of the domain of the ERP from a information across the entire business” (Beheshti, company (or a group of companies) to a subsidiary 2006). -

A Course Material on ENTERPRISE RESOURCE PLANNING by Mr.S

BA 7301 ENTERPRISE RESOURCE PLANNING A Course Material on ENTERPRISE RESOURCE PLANNING By Mr.S.ARUNKUMAR ASSISTANT PROFESSOR DEPARTMENT OF MANAGEMENT SCIENCE SASURIE COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING VIJAYAMANGALAM – 638 056 1 SCE DEPARTMENT OF MANAGEMENT SCIENCE BA 7301 ENTERPRISE RESOURCE PLANNING QUALITY CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the e-course material Subject Code : BA7301 Subject : ENTERPRISE RESOURCE PLANNING Class : II MBA being prepared by me and it meets the knowledge requirement of the university curriculum. Signature of the Author Name : S.Arunkumar Designation: Assistant Professor This is to certify that the course material being prepared by Mr.S.ARUNKUMAR is of adequate quality. se has referred more than five books amount them minimum one is from abroad author. Signature of HD Name : S.ARUNKUMAR SEAL : 2 SCE DEPARTMENT OF MANAGEMENT SCIENCE BA 7301 ENTERPRISE RESOURCE PLANNING CONTENTS CHAPTER TOPICS PAGE NO INTRODUCTION 1.1 Overview of enterprise systems 1.1.1 Introduction 1.1.2 What is ERP 1.1.3 Why ERP 1.1.4 Need for Enterprise Resource Planning 1.1.5 Definition of ERP 6-25 I 1.2 Evolution of Enterprise Resource Planning 1.2.1 Pre material requirement planning (MRP stage) 1.2.2 Material requirement planning 1.2.3 MRP- II 1.2.4 ERP 1.2.5 Extended ERP 1.2.6 ERP Planning –II 1.2.7 ERP-A manufacturing perspective 1.3 Risks and benefits – 1.3.1 Risk implementation 1.4 Fundamental technology of ERP 1.5 Issues to be consider in planning design and implementation of cross functional integrated ERP systems ERP SOLUTIONS AND FUNCTIONAL MODULES 2.1 Overview of ERP software solutions 2.2 Small, medium and large enterprise vendor solutions, 2.3 Business process Reengineering 2.4 Business process Management 2.4.1 Steps of BPM II 2.5 Functional Modules. -

Identifying Organizational Conflict of Interest: the Information Gap

A Publication of the Defense Acquisition University http://www.dau.mil Keywords: Organizational Conflict of Interest (OCI), Organizational Structure, Central Contractor Registration, Transparency Act Identifying Organizational Conflict of Interest: The Information Gap M. A. Thomas As the volume of government contracting increases, so does the importance of monitoring government contrac- tors to guard against Organizational Conflict of Interest (OCI). For contracting officers to identify OCIs, they must be able to identify the relevant business interests of a contractor’s affiliates. This information may be private or not easily obtained. Using newly released data to develop preliminary visualizations of contractor orga- nizational structures shows the organizational structure of many contractors to be complex and multinational. The complexity and the lack of easily available public information make it very unlikely that contracting officers could identify OCIs without substantial improvements in government data collection. 265 Defense ARJ, July 2012, Vol. 19 No. 3 : 265–282 image designed by Diane Fleischer » A Publication of the Defense Acquisition University http://www.dau.mil As government has come to rely more heavily on contractors for goods, services, and advice, it needs to ensure that procurement remains competitive and that contractor performance is not compromised by outside interests. Organizational Conflict of Interest (OCI) refers to conflicts that arise because of conflicting incentives of contractors due to their own activities -

Managing Conflict

7 Managing Conflict onflicts of various types are a natural part of the team process. CAlthough we often view conflict as negative, there are benefits to con- flict if it is managed appropriately. People handle conflict in their teams in a variety of ways, depending on the importance of their desire to maintain good social relations and develop high-quality solutions. Teams can use a variety of approaches for managing conflicts. Developing a healthy solution to a conflict requires open communication, respect for the other side, and a creative search for mutually satisfying alternatives. Learning Objectives 1. Why is the lack of conflict a sign of a problem in a team? 2. What are the healthy and unhealthy sources of conflict? 3. When is conflict good for a team? When is it bad for a team? 4. How does the impact of conflict vary depending on the type of team? 5. What are the different approaches to conflict resolution? 6. Which approach to conflict resolution is best? Why? 7. What can teams do to prepare for conflicts? 8. How can a mediator help facilitate management of a team conflict? 9. What should a team do to create an integrative solution to a conflict? 125 126 Issues Teams Face 7.1 Conflict Is Normal Conflict is the process by which people or groups perceive that others have taken some action that has a negative effect on their interest. Conflict is a normal part of a team’s life. Unfortunately, people have misconceptions about conflict that interfere with how they deal with it. -

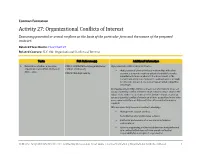

Activity 27: Organizational Conflicts of Interest Examining Potential Or Actual Conflicts on the Basis of the Particular Facts and the Nature of the Proposed Contract

Contract Formation Activity 27: Organizational Conflicts of Interest Examining potential or actual conflicts on the basis of the particular facts and the nature of the proposed contract. Related Flow Charts: Flow Chart 27 Related Courses: CLC 132: Organizational Conflicts of Interest Tasks FAR Reference(s) Additional Information 1. Determine whether a possible FAR 2.101 Definitions [organizational Organizational conflict of interest means— organizational conflict of interest conflict of interest]. that because of other activities or relationships with other (OCI) exists. FAR 9.502 Applicability. persons, a person is unable or potentially unable to render impartial assistance or advice to the Government, or the person's objectivity in performing the contract work is or might be otherwise impaired, or a person has an unfair competitive advantage. An organizational conflict of interest may result when factors create an actual or potential conflict of interest on an instant contract, or when the nature of the work to be performed on the instant contract creates an actual or potential conflict of interest on a future acquisition. In the latter case, some restrictions on future activities of the contractor may be required. OCIs are more likely to occur in contracts involving— Management support services; Consultant or other professional services; Contractor performance of or assistance in technical evaluations; or Systems engineering and technical direction work performed by a contractor that does not have overall contractual responsibility for development or production. FEDERAL ACQUISITION INSTITUTE | Contracting Professionals Smart Guide | Contract Formation | Organizational Conflicts of Interest 1 Tasks FAR Reference(s) Additional Information Each individual contracting situation should be examined on the basis of its particular facts and the nature of the proposed contract.