Marine Debris and Plastics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plumbing Guidelines for ADA Accessibility

Plumbing Guidelines for ADA Accessibility Course No: M01-004 Credit: 1 PDH Steven Liescheidt, P.E., CCS, CCPR Continuing Education and Development, Inc. 9 Greyridge Farm Court Stony Point, NY 10980 P: (877) 322-5800 F: (877) 322-4774 [email protected] Appendix A to Part 1191 - Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) Accessibility Guidelines for Buildings and Facilities Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) Accessibility Guidelines for Buildings and Facilities U.S. Architectural and Transportation Barriers Compliance Board (Access Board) 1331 F Street, N.W., Suite 1000 Washington, D.C. 20004-1111 (202) 272-0080 (202) 272-0082 TTY (202) 272-0081 FAX 4.16 Water Closets. mm) that allows a person in a wheelchair to make 4.16.1 General. Accessible water closets shall a parallel approach to the unit (see Fig. 27(c) and comply with 4.16.2 through 4.16.6. (d)). This clear floor space shall comply with 4.2.4. EXCEPTION: Water closets used primarily by children ages 12 and younger shall be permitted 4.16 Water Closets. to comply with 4.16.7. Fig. 27 Drinking Fountains and Water Coolers 45 4.17 Toilet Stalls. 4.16.2 Clear Floor Space. Clear floor space for bar centerline. The grab bar behind the water water closets not in stalls shall comply with Fig. closet shall be 36 in (915 mm) minimum. 28. Clear floor space may be arranged to allow either a left-handed or right-handed approach. EXCEPTION: If administrative authorities require flush controls for flush valves to be located in a 4.16.3* Height. -

How to Clean and Care Your Stainless Steel Sink

How to Clean and Care Your Stainless Steel Sink Our Stainless Steel Sinks are made of the highest quality 304 series stainless steel. This elegant, heavy-duty, 16 or 18 gauge, non-porous material is hygienic, and extremely durable. Our satin- polished finish creates an enduring, easy-to-clean luster. Regardless of whether your sink is made of stainless steel, composite, porcelain, or enamel, the sink will require periodic cleaning to maintain the original finish. 3 Simple Steps in Caring for Your Sink Clean regularly with a mild detergent solution and/or clean water applied with a soft cloth or sponge. Rinse and towel dry after every use to prevent mineral deposits from building up on the surface of the sink. Deep clean once a week with an approved cleanser (be sure to rub in the direction of the finish lines) and a soft cloth or sponge rather than an occasional aggressive single cleaning. Cleaners should state approved or suitable for stainless steel. General Care and Cleaning After every use, rinse thoroughly, then wipe the sink dry with a clean soft cloth. Wiping is key; this will inhibit water spotting and mineral deposits in severe hard water conditions. Bar Keepers Friend, Flitz, Gordon's or Miracle Shine, (follow directions on product) are products available in hardware and grocery stores that can be used every day to protect, polish, and clean your sink. Water Quality Regular routine cleaning can usually prevent lime scale deposits from hard water. Do not allow excessive build up before treating. Soaking in a 25% vinegar solution can treat hard water spots. -

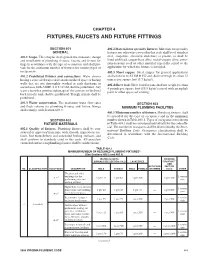

Chapter 4 Fixtures, Faucets and Fixture Fittings

Color profile: Generic CMYK printer profile Composite Default screen CHAPTER 4 FIXTURES, FAUCETS AND FIXTURE FITTINGS SECTION 401 402.2 Materials for specialty fixtures. Materials for specialty GENERAL fixtures not otherwise covered in this code shall be of stainless 401.1 Scope. This chapter shall govern the materials, design steel, soapstone, chemical stoneware or plastic, or shall be and installation of plumbing fixtures, faucets and fixture fit- lined with lead, copper-base alloy, nickel-copper alloy, corro- tings in accordance with the type of occupancy, and shall pro- sion-resistant steel or other material especially suited to the vide for the minimum number of fixtures for various types of application for which the fixture is intended. occupancies. 402.3 Sheet copper. Sheet copper for general applications 401.2 Prohibited fixtures and connections. Water closets shall conform to ASTM B 152 and shall not weigh less than 12 having a concealed trap seal or an unventilated space or having ounces per square foot (3.7 kg/m2). walls that are not thoroughly washed at each discharge in 402.4 Sheet lead. Sheet lead for pans shall not weigh less than accordance with ASME A112.19.2M shall be prohibited. Any 4 pounds per square foot (19.5 kg/m2) coated with an asphalt water closet that permits siphonage of the contents of the bowl paint or other approved coating. back into the tank shall be prohibited. Trough urinals shall be prohibited. 401.3 Water conservation. The maximum water flow rates SECTION 403 and flush volume for plumbing fixtures and fixture fittings MINIMUM PLUMBING FACILITIES shall comply with Section 604.4. -

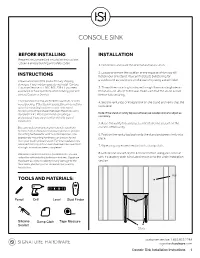

Console Sink

CONSOLE SINK BEFORE INSTALLING INSTALLATION Read entire Console Sink Installation Instructions. Observe all local building and safety codes. 1. Determine and mark the sink installation location. 2. Locate and mark the location of the studs to which you will INSTRUCTIONS fasten your sink stand. You can find studs by listening for Unpack and inspect the product for any shipping a solid sound as you knock on the wall or by using a stud finder. damages. If you find damages, do not install. Contact Customer Service at 1-866-855-2284. If you need 3. Thread the mounting hardware through the mounting holes in assistance or have questions while installing your sink, the stand and attach to the wall. Make sure that the stand is level contact Customer Service. before fully securing. Console sinks must be anchored to wall studs or solid 4. Set the vanity top or integral sink on the stand and verify that the wood blocking. If the studs in your bathroom do not line top is level. up to the mounting location for your sink, wood blocking should be installed between the studs using standard 2 x 4’s. We recommend consulting a Note: If the stand or vanity top are not level use wooden shims to adjust as necessary. professional if you are unfamiliar with this type of installation. 5. Raise the vanity top and place a dot of silicone sealant on the Because wall construction and materials vary from corners of the vanity. home to home, Signature Hardware does not provide mounting hardware for all of our console sinks. -

Granite Composite Sink Installation Instructions

GRANITE COMPOSITE SINK INSTALLATION INSTRUCTIONS CONTENTS Sink Installation Faucet Drilling 2 Drop-In Sink 3 Undermount Sink 4 Drain Installation 5 Materal Care and Maintenance 6 Granite Composite Sink Installation Instructions 1 FAUCET DRILLING BEFORE INSTALLING INSTALLATION Read entire installation instructions. The hole for the faucet can be drilled from either side of Observe all local building and safety codes. the drop-in sink, depending on your installation needs. Drill the faucet hole with a 35mm diamond drill bit at the appropriate location. INSTRUCTIONS Pre-marked hole locations are on the underside of the faucet For this installation it is assumed that the deck for guidance. However, faucet holes may be drilled counter-top has been cut to the dimensions wherever necessary. of the sink. We recommend consulting a professional if you are unfamiliar with this type of installation. Signature Hardware accepts no liability for any damages to the floor, walls, plumbing or for personal injury during installation. Unpack and inspect the product for any shipping damages. If you find damages, do not install. Contact Customer Service at 1-866-855-2284. If you need assistance or have questions while installing your sink, contact Customer Service. TOOLS AND MATERIALS: 35mm Diamond Drill Drill Bit Granite Composite Sink Installation Instructions 2 DROP-IN SINK BEFORE INSTALLING INSTALLATION Read entire installation instructions. 1. Lower the sink into the sink cutout on the counter to Observe all local building and safety codes. confirm the sink will fit properly. The perimeter of the sink rim should connect with the counter while the sink bowl should sit completely inside the counter. -

Tips for Installing Saniflo® Products

TIPS FOR INSTALLING SANIFLO ® PRODUCTS EXTENSION PIPE MINIMUM SIZE DISCHARGE PIPE The macerating pumps can All the pump units must have a minimum of three feet of be installed stand alone or the required size of discharge pipe before transitioning EASILY AND QUICKLY INSTALL A TOILET, BATHROOM OR LAUNDRY ROOM ANYWHERE IT’S NEEDED! behind the wall with the use of to a larger pipe size. This transition can only be an extension pipe (maximum implemented in the last horizontal pitched discharge SANIFLO ® MACERATING TOILET SYSTEMS length 18"). The bowl must line. This will allow the pump to operate for an 3 External Units be raised by ⁄8". Can only adequate period of time to ensure efficient waste ® be used with the Sanitop, Saniplus and Sanibest. reduction. SANITOP : used for toilet, sink SANIPLUS ®: used for toilet, sink, • Build a half bathroom for bathtub, shower PIPE SUPPORTS SOIL STACK CONNECTION residential applications Quiet Design • Build a complete bathroom for Quiet Design All sanitary pipe work must be supported in accordance The discharge pipe must be connected to the soil stack • Vertical pumping up to 12 ft. residential applications and 120 ft. horizontally with the pipe manufacturers recommendations to avoid by an appropriate and approved connection. • Vertical pumping up to 15 ft. and 150 ft. dipping which may cause the build up of residual waste • Designed to work with our rear discharge horizontally PIPE WORK MATERIAL toilet that only uses 1.6 gallons (6 liters) of water per flush and subsequent blockage. • Designed to work with our rear discharge toilet that only uses 1.6 All discharge pipe work should be made out of ridged gallons (6 liters) of water per flush BENDS copper or PVC/CPVC (schedule 40). -

ADA Design Guide Washrooms & Showers

ADA Design Guide Washrooms & Showers Accessories Faucets Showers Toilets Lavatories Interactive version available at bradleycorp.com/ADAguide.pdf Accessible Stall Design There are many dimensions to consider when designing an accessible bathroom stall. Distances should allow for common usage by people with a limited range of motion. A Dimension guidelines when dispensers protrude from the wall in toilet rooms and 36" max A toilet compartments. 915 mm Anything that a person might need to reach 24" min should be a maximum of 48" (1220 mm) off of 610 mm the finished floor. Toilet tissue needs to be easily within arm’s 12" min reach. The outlet of a tissue dispenser must 305 mm be between 24" (610 mm) minimum and 42" (1070 mm) maximum from the back wall, and per the ANSI standard, at least 24" min 48" max 18" above the finished floor. The ADA guide 610 mm 1220 mm defines “easily with arm’s reach” as being within 7-9" (180–230 mm) from the front of 42" max the bowl and at least 15" (380 mm) above 1070 mm the finished floor (48" (1220 mm) maximum). Door latches or other operable parts cannot 7"–9" 18" min 180–230 mm require tight grasping, pinching, or twisting of 455 mm the wrist. They must be operable with one hand, using less than five pounds of pressure. CL Dimensions for grab bars. B B 39"–41" Grab Bars need to be mounted lower for 990–1040 mm better leverage (33-36" (840–915 mm) high). 54" min 1370 mm 18" min Horizontal side wall grab bars need to be 12" max 455 mm 42" (1065 mm) minimum length. -

Buildings As a Global Carbon Sink

PERSPECTIVE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0462-4 Buildings as a global carbon sink Galina Churkina 1,2*, Alan Organschi3,4, Christopher P. O. Reyer 2, Andrew Ruff3, Kira Vinke2, Zhu Liu 5, Barbara K. Reck 1, T. E. Graedel 1 and Hans Joachim Schellnhuber2 The anticipated growth and urbanization of the global population over the next several decades will create a vast demand for the construction of new housing, commercial buildings and accompanying infrastructure. The production of cement, steel and other building materials associated with this wave of construction will become a major source of greenhouse gas emissions. Might it be possible to transform this potential threat to the global climate system into a powerful means to mitigate climate change? To answer this provocative question, we explore the potential of mid-rise urban buildings designed with engineered timber to provide long-term storage of carbon and to avoid the carbon-intensive production of mineral-based construction materials. uring the Carboniferous period, giant fern-like woody evolved. Furthermore, current rates of fossil fuels combustion have far plants grew in vast swamps spread across the Earth’s sur- exceeded carbon sequestration rates in forests creating the need for Dface. As successions of these plants grew and then toppled, national governments to submit reduction targets for CO2 emissions they accumulated as an increasingly dense mat of fallen plant mat- to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change ter. Some studies have suggested that this material resisted decay (UNFCCC) as part of their obligations under the Paris Agreement16. because microbes that would decompose dead wood were not yet However, even if all governments were to achieve their commitments, 1 present , while others have argued that a combination of climate anthropogenic CO2 emissions would exceed the carbon budget range and tectonics buried the dead wood and prevented its decomposi- associated with the agreement17. -

Installation Guide

Installation Guide Install your new sink with step-by-step instructions. Installation Guide Bath Sinks Drop-In 4 Undermount 6 Dual Flex 9 Vessel 10 Drains 12 Bathtubs Freestanding 16 Overflow and Waste Kit 18 Rough-In Kit 20 Kitchen + Bar Sinks Drop-In 24 Undermount 28 Farmhouse 30 Drains 36 Fireclay 40 Bath Sinks DIY Bath Sinks: Drop-In PRO Drop-In sinks are designed to be easy to install in a wide range of countertop to secure the sink countertop materials. Sinkology copper sinks make updating your in place. bathroom design effortless. 5. Use plumbers putty on the Important underside of the drain lip to Sinkology bathroom drop-in sinks do not use mounting hardware. Our seal the drain to the sink. See preferred mounting method requires expanding foam and 100% silicone diagram. to secure your copper sink into place. 6. Apply Sinkology antique brown or clear neutral cure 100% silicone around the rim of 1. Flip sink upside down and trace outside edge onto craft paper the sink to form a water tight seal. See our Complete Silicone or cardboard. Add a second line 1/2” inch inside the first line. Installation Kit (#SINSTALL-101) for Copper Sinks. Cut out the center of the template using the second line. 7. For regular maintenance simply wash with gentle soap 2. Place the template on the countertop and trace the template. and water. For extra protection against water spotting, use Cut the installation hole in the countertop. Sinkology Copper Armor care kit (#SARMOR-101) or high quality carnauba wax. -

Much Ado About the Kitchen Sink

Much Ado About the Kitchen Sink March 29, 2016 A couple of weeks ago, we published an article about a universal design for kitchen sink workstations developed with Ken Kelly using a sink from BLANCO, and I realized we have yet to provide an overview of the latest and greatest options for kitchen sinks. Not so long ago, the choices for sinks were slim, and nearly everyone was satisfied with porcelain, enameled iron or stainless steel drop-ins/top-mounts. Although the above styles still remain both common and popular, several new types and models of kitchen sinks have entered the market and are making decisions tough for consumers and commercial building owners. As our industry survey revealed last year, countertop fabricators hold a great deal of sway over their clients, so by understanding all of the options, you can stock kitchen sinks that both meet the needs of your clients and provides a solid profit margin for your business. Farmhouse Sinks One popular style of kitchen sinks that has come back into the spotlight like a blast from the past is the farmhouse sink with apron front. These large, deep, tub-like sinks originated in England more than 400 years ago. They were designed to hold large amounts of water, which often had to be hauled from miles away. Farmhouse sinks are often the focal point of a kitchen, so many clients like to make them special. Stainless steel and enameled cast iron are both materials that are common used for these sinks, but several new materials are now available, including fireclay, hammered metal, concrete composite and quartz/granite composite (as outlined above). -

Wholesale Undermount Sink Distribution

Wholesale Undermount Sink Distribution Sink Source 8823 Zealand Ave N Suite P Brooklyn Park, MN 55445 763-315-6617 [email protected] sinksource.com U U PC PC sinksource.com ® ® C 2021 PRODUCT CATALOG sinksource.com CONTENTS Stainless Steel Sinks 2 NEW! Granítis Granite Composite 8 Wholesale Undermount Sink Distribution Sink Collection As the Midwest’s leading undermount sink distributor, we take pride in offering high-quality kitchen and NEW! Neró Near Zero Radius 2 bathroom sinks and accessories. We are passionate about providing expert service and selection, and Sink Collection include professional guidance on all orders. Our reputation has been built on supplying quality products Porcelain Bathroom Vanity Sinks 10 at fair prices to partners in the construction industry. Double Bowl Kitchen Sinks 4 Sink Source carries an extensive variety of styles and finishes of sinks, including 304-series stainless steel sinks, luxurious granite composite sinks, and gorgeous porcelain vanity bowls. All of our products are Accessories and Supplies 12 UPC and cUPC designated, and come with a limited lifetime warranty. Single Bowl Kitchen Sinks 6 Our two new sink collections offer innovative and contemporary options to compliment any kitchen or space. Bar Sinks 7 Care and Maintenance 13 • Neró Near Zero Radius Collection – These rectangular stainless steel basins have straight side panels brought together by precisely angled, tight corner degrees that create simple, straight lines. • Granítis Granite Composite Collection – This German-made material is engineered for superior quality by using a mixture of ground granite stone and acrylic resin under high pressure. The resulting surface is nonporous, naturally hygienic, and resistant to heat, stains, scratches, and chips. -

Top Mount Single Bowl Sink Product Specifications

25” X 22” Top Mount Single Bowl Sink Product Specifications PRODUCT FEATURES • 23 Gauge • 300 Series Stainless Steel • Satin Finish • Sound Absorption Pads MATERIALS & SPECIFICATIONS Installation Type: Top Mount Material: 300 Series Stainless Steel Finish: Satin Gauge: 23 MLK25224 shown Sound Deadening: Bottom Only Pads Number of Bowls: 1 Sink Dimensions: 25” x 22” x 6-1/16” Bowl Dimensions: 21” x 15-3/4” x 5-7/8” Drain Size: 3-1/2” (89mm) Drain Location: Center Minimum Cabinet Size: 30” Part# 64090012 included for Mounting Hardware: countertops up to ¾” (19mm) thick Cutout Template #: Available on Mainline Collection.com This sink is compliant to ADA and ANSI/ICC A117.1 accessibility requirements when installed according to the To requirements outlined in these standards. Submit Part No. Description Sinks are listed by IAPMO® as meeting the applicable MLK25223 Three Hole requirements of the Uniform Plumbing Code®, International Plumbing Code®, and National Plumbing MLK25224 Four Hole Code of Canada. These sinks comply with ASMEA112.19.3/CSA B45.4 Warranty: See warranty information for more details. All dimensions listed are nominal. MAINLINE® reserves the right to make product and material changes at any time without notice. Contact your sales representative for more information or visit our website at mainlinecollection.com Revised 5/24/2019 25” X 22” Top Mount Single Bowl Sink Product Specifications DIMENSIONS Installation Profile: CUT OUT DIMENSIONS FOR TOP MOUNT INSTALLATION • 24-3/8” X 21-3/8” (619mm x 543mm) with 1-1/2” corner radius HOLE DRILLING CONFIGURATION • 1-1/2” (38mm) Diameter Faucet Holes • Faucet holes on 4” (102mm) centers Warranty: See warranty information for more details.