Religion, Modernity, and the Nation: Postscripts of Malabar Migration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pathanamthitta

Census of India 2011 KERALA PART XII-A SERIES-33 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PATHANAMTHITTA VILLAGE AND TOWN DIRECTORY DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS KERALA 2 CENSUS OF INDIA 2011 KERALA SERIES-33 PART XII-A DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK Village and Town Directory PATHANAMTHITTA Directorate of Census Operations, Kerala 3 MOTIF Sabarimala Sree Dharma Sastha Temple A well known pilgrim centre of Kerala, Sabarimala lies in this district at a distance of 191 km. from Thiruvananthapuram and 210 km. away from Cochin. The holy shrine dedicated to Lord Ayyappa is situated 914 metres above sea level amidst dense forests in the rugged terrains of the Western Ghats. Lord Ayyappa is looked upon as the guardian of mountains and there are several shrines dedicated to him all along the Western Ghats. The festivals here are the Mandala Pooja, Makara Vilakku (December/January) and Vishu Kani (April). The temple is also open for pooja on the first 5 days of every Malayalam month. The vehicles go only up to Pampa and the temple, which is situated 5 km away from Pampa, can be reached only by trekking. During the festival period there are frequent buses to this place from Kochi, Thiruvananthapuram and Kottayam. 4 CONTENTS Pages 1. Foreword 7 2. Preface 9 3. Acknowledgements 11 4. History and scope of the District Census Handbook 13 5. Brief history of the district 15 6. Analytical Note 17 Village and Town Directory 105 Brief Note on Village and Town Directory 7. Section I - Village Directory (a) List of Villages merged in towns and outgrowths at 2011 Census (b) -

From Little Tradition to Great Tradition: Canonising Aithihyamala NIVEA THOMAS K S

From Little Tradition to Great Tradition: Canonising Aithihyamala NIVEA THOMAS K S. ARULMOZI Abstract In an attempt to reinvent the tradition of Kerala in the light of colonial modernity, Kottarathil Sankunni collected and transcribed the lores and legends of Kerala in his work Aithihyamala in 1909. When the legends were textualised, Sankunni attributed certain literary values to the narratives to legitimise the genre. As it was a folk appropriation by a scholarly elite like Sankunni who had received English education during the colonial period, the legends moved from folk tradition to classical tradition. In their transition from Little Tradition to Great Tradition, the legends underwent huge transformation in terms of form, content, language, context and narrative style. The text became fixed, stable and structured and was eventually subjected to a canon. However, when one perceives Aithihyamala (1909) as the ‘authentic’ and the ‘final’ version of the legends in Kerala, one is neglecting and silencing the multiple oral versions and folk tradition that had been existing since the pre-literate period. The current study attempts to trace the transformation undergone by the text when it moved towards the direction of a literary canon. Keywords: Legends Transcription, Great Tradition, Little Tradition, Literary Canon. Introduction Aithihyamala, a collection of lores and legends of Kerala was compiled by Kottarathil Sankunni in Bhashaposhini magazine in the beginning of the twentieth century. In his preface to DOI: 10.46623/tt/2020.14.1.ar4 Translation Today, Volume 14, Issue 1 Nivea Thomas K & S. Arulmozi Aithihyamala (1909) which comprises 126 legends, Sankunni (2017: 89) states that the text had been harshly criticised by an anonymous writer on the grounds of its casual nature. -

Cultural Heritage of Kerala - 9788126419036 - D.C

A. Sreedhara Menon - 2008 - Cultural Heritage of Kerala - 9788126419036 - D.C. Books, 2008 Cultural Heritage of Kerala Kerala History and its Makers Kerala district gazetteers, Volume 1 Kerala District Gazetteers: Alleppey Kerala District Gazetteers: Malappuram Punnapr̲a VayalÄr̲uṃ, KÄ“raḷacaritr̲avuṃ Find Deals & PDF download Cultural Heritage of Kerala. by A. Sreedhara Menon Book Views: 0. Author. A. Sreedhara Menon. Publisher. Date of release. 0000-00-00. Pages. A. Sreedhara Menon depicts a broad picture of the life and culture of the people of Kerala. It is a study of the evolution of Kerala culture in the general background of Indian culture. This book covers all fields of life and activity in Kerala- religious, artistic, social, economic, and political, and stresses the theme of integrative and assimilative tradition of Kerala culture. Sreedhara Menon was an eminent historian and former Head of the Department of History, University of Kerala. Read more.. Error in review? Submit review. Find & Download Book â” Cultural Heritage of Kerala. KERALA. : The cultural heritage of any country is seen best exposed in its architectural monuments. The ways in which the buildings are designed, constructed and decorated speak not only the technical and artistic capabilities of the craftsmen, but also of the aspirations and visions of the perceptors, for whom the construction is only a medium for thematic expression. Pre-historic Vestiges The locational feature of Kerala has influenced the social development and indirectly the style of construction. In the ancient times the sea and the Ghats formed unpenetrable barriers helping the evolution of an isolated culture of Proto Dravidians, contemporary to the Harappan civilization. -

National Innovation Challenge

ATAL INNOVATION MISSION | NITI AAYOG AIC - IIIT KOTTAYAM An incubation centre of the Indian Institute of Information Technology Kottayam A I C - I I I T K O T T A Y A M NATIONAL INNOVATION CHALLENGE Come with an idea and return as a startup R E G I S T R A T I O N S T A R T E D F R O M 5 T H J U L Y Register now and don't miss out on this life-changing event! Registered firms, Colleges, Schools can participate. NO GUTS NO GLORY WHAT WE OFFER TOP THREE finalists will receive a spot in the incubation centre with a pre-seed/ ignition fund in phases. Qualified EIGHT finalists will receive a spot in incubation centre and will be accommodated as self-financed entities. Selected finalists will receive a direct feedback from an experienced panel, and will get a support to advance their startups. All participants will receive an official certificate of participation from the AIC-IIIT-K. Free pass to registered firms to attend the seminars and workshops conducted by AIC. All participant schools/colleges will be enrolled as a nodal centre of AIC-IIIT-K with out an additional fee. HIT THE JACKPOT PAY AND REGISTER 1. Make the payment For School/Colleges - Rs. 15000/- For Registered firms - Rs. 2500/- Payment can be done using SBI Collect or a fund transfer to Account Name: AIC-IIITKottayamFoundation Account Number: 37794141455 Bank Name: State Bank of India, Valavoor, Pala, Kottayam District, Kerala. IFSC: SBIN0070539 2. Register for the competition by click / scan on the below link. -

Iiitk Fdp Dec 7-11{2}

A bout the Departments A bout the Institute Dept. of CSE and ECE offers 4 year B.Tech Indian Institute of Information Technology, and BTech (Hons) program with Kottayam at Valavoor, Pala, Kerala is one specialized courses covering all major among the IIITs that have been established research domains of Computer Science as "Institution of National Importance" by Engineering and Electronics and MHRD Govt. of India under the ambit of IIIT Communication Engineering. Dept. of CSE PPP act 2017. IIIT Kottayam campus is DEPARTMENT OF ECE & CSE also offers MTech in AI & Data Science for situated at Valavoor, Pala, Kottayam- a working professionals. PhD programs are picturous location, spread over in 53 acres of offered in ECE, CSE and Mathematics. land - allotted by Govt. of Kerala in the Patrons southern part of the Country commonly Prof. (Dr.) Rajiv Dharaskar referred to as God's Own Country. B.Tech Director, IIIT Kottayam. students are admitted against the Dr. M. Radhakrishnan JoSAA/CSAB counselling against the JEE main rank list. Registrar, IIIT Kottayam. Internet of Things: Prof. (Dr.) P. Mohanan Address Indian Institute of Information Technology Hardware, Software and Prof.In-Charge (Academics) Kottayam, Valavoor P O.. Applications IIIT Kottayam. Pala,, Kottayam- 686635, Kerala 5-Day Faculty Development Contact details Visit us at www.iiitkottayam.ac.in FDP Coordinator Programme (Online) Dr. Kala S 7-11 DECEMBER 2020 Assistant Professor, SPONSORED BY Indian Institute of Information Technology Kottayam Contact: 0482 2202167 Email: [email protected] Logistics: Mr. Deshaboina Yashwanth BTech- CSE,, IIIT Kottayam Contact: +91 9390221814 About the FDP Resource Persons Selection The five-day Faculty Development The selected participants will be intimated Programme on “Internet of Things: Hardware, 1. -

Analysing Lee's Hypotheses of Migration in the Context of Malabar

International Journal of Research in Geography (IJRG) Volume 4, Issue 1, 2018, PP 1-8 ISSN 2454-8685 (Online) http://dx.doi.org/10.20431/2454-8685.0401001 www.arcjournals.org Analysing Lee’s Hypotheses of Migration in the Context of Malabar Migration: A Case Study of Taliparamba Block, Kannur District Surabhi Rani 1 Dept.of Geography, Kannur University Payyanur Campus, Edat. P.O ,Payyanur, Kannur, Kerala Abstract: Human Migration is considered as one of the important demographic process which has manifold effect on the society as well as to the individuals, apart from the other population dynamics of fertility and mortality. Several approaches dealing with migration has evolved the concepts related to the push and pull factors causing migration. Malabar Migration is a historical phenomenon of internal migration, in which massive exodus took place in the vast jungles of Malabar concentrating with similar socio-cultural-economic group of people. Various factors related to social, cultural, demographical and economical aspects initiated the migration from erstwhile Travancore to erstwhile Malabar district. The present preliminary study tries to focus over such factors associated with Malabar Migration in Taliparamba block of Kannur district (Kerala).This study is based on the primary survey of the study area and further supplemented with other secondary materials. Keywords: migration, push and pull factors, Travancore, Malabar 1. INTRODUCTION Human migration is one of the few truly interdisciplinary fields of research of social processes which has widespread consequences for both, individuals and the society. It is a sort of geographical or spatial mobility of people with change in their place of residence and socio-cultural environment. -

Masculinity and the Structuring of the Public Domain in Kerala: a History of the Contemporary

MASCULINITY AND THE STRUCTURING OF THE PUBLIC DOMAIN IN KERALA: A HISTORY OF THE CONTEMPORARY Ph. D. Thesis submitted to MANIPAL ACADEMY OF HIGHER EDUCATION (MAHE – Deemed University) RATHEESH RADHAKRISHNAN CENTRE FOR THE STUDY OF CULTURE AND SOCIETY (Affiliated to MAHE- Deemed University) BANGALORE- 560011 JULY 2006 To my parents KM Rajalakshmy and M Radhakrishnan For the spirit of reason and freedom I was introduced to… This work is dedicated…. The object was to learn to what extent the effort to think one’s own history can free thought from what it silently thinks, so enable it to think differently. Michel Foucault. 1985/1990. The Use of Pleasure: The History of Sexuality Vol. II, trans. Robert Hurley. New York: Vintage: 9. … in order to problematise our inherited categories and perspectives on gender meanings, might not men’s experiences of gender – in relation to themselves, their bodies, to socially constructed representations, and to others (men and women) – be a potentially subversive way to begin? […]. Of course the risks are very high, namely, of being misunderstood both by the common sense of the dominant order and by a politically correct feminism. But, then, welcome to the margins! Mary E. John. 2002. “Responses”. From the Margins (February 2002): 247. The peacock has his plumes The cock his comb The lion his mane And the man his moustache. Tell me O Evolution! Is masculinity Only clothes and ornaments That in time becomes the body? PN Gopikrishnan. 2003. “Parayu Parinaamame!” (Tell me O Evolution!). Reprinted in Madiyanmarude Manifesto (Manifesto of the Lazy, 2006). Thrissur: Current Books: 78. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Kottayam District from 17.05.2020To23.05.2020

Accused Persons arrested in Kottayam district from 17.05.2020to23.05.2020 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Cr. No. 646/20 ERUMANGALATH H, U/S MINI CIVIL 18.05.20 KOTTAYAM 1 PHILIP JOSEPH JOSEPH 62 KUMARANALLOOR 2336,269,188 SREEJITH T BAILED STATION 12:02 Hrs WEST PS PO, KOTTAYAM IPC & 4(2)(a) OF KEPDO Cr. No. 646/20 BHAGAVATHY U/S MUHAMMED PARAMBIL H, MINI CIVIL 18.05.20 KOTTAYAM 2 ABDUL KHADER 52 2336,269,188 SREEJITH T BAILED BASHEER KARAPPUZHA PO, STATION 12:02 Hrs WEST PS IPC & 4(2)(a) KOTTAYAM OF KEPDO Cr. No. 646/20 KALAALAYAM H, U/S UNNIKRISHNA MINI CIVIL 18.05.20 KOTTAYAM 3 BHASKARAN 58 PADINJAREMURY 2336,269,188 SREEJITH T BAILED N STATION 12:02 Hrs WEST PS BHAGOM, VAIKOM IPC & 4(2)(a) OF KEPDO Cr. No. 646/20 VILLATHARA H, U/S MINI CIVIL 18.05.20 KOTTAYAM 4 SASI GOPALAKRISHNAN 44 NAGAMBADOM, 2336,269,188 SREEJITH T BAILED STATION 12:02 Hrs WEST PS KOTTAYAM IPC & 4(2)(a) OF KEPDO Cr. No. 646/20 KOMALAPURAM H, U/S AVARMMA, MINI CIVIL 18.05.20 KOTTAYAM 5 SAJEEVAN RAKHAVAN NAIR 50 2336,269,188 SREEJITH T BAILED PERUMBADAVU, STATION 12:02 Hrs WEST PS IPC & 4(2)(a) KOTTAYAM OF KEPDO Cr. -

Marxist Praxis: Communist Experience in Kerala: 1957-2011

MARXIST PRAXIS: COMMUNIST EXPERIENCE IN KERALA: 1957-2011 E.K. SANTHA DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SIKKIM UNIVERSITY GANGTOK-737102 November 2016 To my Amma & Achan... ACKNOWLEDGEMENT At the outset, let me express my deep gratitude to Dr. Vijay Kumar Thangellapali for his guidance and supervision of my thesis. I acknowledge the help rendered by the staff of various libraries- Archives on Contemporary History, Jawaharlal Nehru University, C. Achutha Menon Study and Research Centre, Appan Thampuran Smaraka Vayanasala, AKG Centre for Research and Studies, and C Unniraja Smaraka Library. I express my gratitude to the staff at The Hindu archives and Vibha in particular for her immense help. I express my gratitude to people – belong to various shades of the Left - who shared their experience that gave me a lot of insights. I also acknowledge my long association with my teachers at Sree Kerala Varma College, Thrissur and my friends there. I express my gratitude to my friends, Deep, Granthana, Kachyo, Manu, Noorbanu, Rajworshi and Samten for sharing their thoughts and for being with me in difficult times. I specially thank Ugen for his kindness and he was always there to help; and Biplove for taking the trouble of going through the draft intensely and giving valuable comments. I thank my friends in the M.A. History (batch 2015-17) and MPhil/PhD scholars at the History Department, S.U for the fun we had together, notwithstanding the generation gap. I express my deep gratitude to my mother P.B. -

File Download

Success doesn’t come to you, you go to it. Table of Contents Introduction Life at IIITK Director’s Message 04 Demographics 09 Dean’s Message 05 Education and 10 Curriculum Registrar’s Message 06 About IIITK 07 Recruitment Reasons to recruit 14 Reach Us 18 International Relations 15 Contact Us 19 Past Recruiters 16 Internships 17 03 IIIT Kottayam has demonstrated rapid progress in its four years of existence. Having managed to set up a permanent campus despite the terrible weather conditions and the back to back floods, is testament to the resilience of our faculty. One among the other innovations is a fully functioning student run mess committee which manages to serve 300 students 3 meals a day along with snacks . With pride it can be said that not a single day has the mess committee failed to deliver what it promised. Moving higher on Maslow's hierarchy of needs, our students' need for intellectual stimulation is readily satisfied by a dynamically changing syllabus sensitive to the developments of the industry. We wish to instill the temperament of research in our students and thus have architected a syllabus focusing on emerging fields in data science Dr. Rajiv V. Dharaskar and artificial intelligence. To give our students an understanding of how management of DIRECTOR funds and people takes place in the real world we have also decided to introduce single IIIT KOTTAYAM credit business courses into our syllabus. The combination of the two disciplines gives our students an all rounded perspective of the industry's challenges and prepares them to take on any situation head- on. -

Library Stock.Pdf

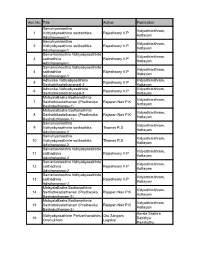

Acc.No. Title Author Publication Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 1 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 2 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 3 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 4 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Adhunika Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 5 Rajeshwary V.P Saithathikadisthanangal-2 Kottayam Adhunika Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 6 Rajeshwary V.P Saithathikadisthanangal-2 Kottayam MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Vidyarthimithram, 7 Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika Rajapan Nair P.K Kottayam Bashabothanam-1) MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Vidyarthimithram, 8 Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika Rajapan Nair P.K Kottayam Bashabothanam-1) Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 9 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Thomas R.S Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 10 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Thomas R.S Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 11 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 12 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 13 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Vidyarthimithram, 14 Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika Rajapan Nair P.K Kottayam Bashabothanam-2) MalayalaBasha -

Kollam Port : an Emporium of Chinese Trade

ADVANCE RESEARCH JOURNAL OF SOCIAL SCIENCE A REVIEW Volume 9 | Issue 2 | December, 2018 | 254-257 ISSN–0976–56111 DOI: 10.15740/HAS/ARJSS/9.2/254-257 Kollam Port : An emporium of Chinese trade H. Adabiya Department of History, Iqbal College, Peringammala, Thiruvananthapuram (Kerala) India Email: adabiyaiqbal@gmail. com ARTICLE INFO : ABSTRACT Received : 21.10.2018 Kerala had maintained active trade relations across the sea with many countries of the Accepted : 26.11.2018 Eastern and Western world. Kollam or Quilon was a major trading centre on the coast of Kerala from the remote past and has a long drawing attraction worldwide. The present paper seeks to analyze the role and importance of Kollam port in the trade KEY WORDS : relation with China. It is an old sea port town on the Arabian coast had a sustained Maritime relations, Emporium, commercial reputation from the days of Phoenicians and the Romans. It is believed Chinese trade, Commercial hub that Chinese were the first foreign power who maintains direct trade relation with Kollam. It was the first port where the Chinese ships could come through the Eastern Sea. Kollam had benefitted largely from the Chinese trade, the chief articles of export from Kollam were Brazil wood or sapang, spices, coconut and areca nut. All these HOW TO CITE THIS ARTICLE : goods had great demand in China and the Chinese brought to Kerala coast goods like Adabiya, H. (2018). Kollam port : An emporium of Chinese trade. Adv. Res. J. silk, porcelain, copper, quick silver, tin, lead etc. Chinese net and ceramics of China Soc.