Nietzsche on Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nietzsche and Aestheticism

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 1992 Nietzsche and Aestheticism Brian Leiter Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Brian Leiter, "Nietzsche and Aestheticism," 30 Journal of the History of Philosophy 275 (1992). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Notes and Discussions Nietzsche and Aestheticism 1o Alexander Nehamas's Nietzsche: L~fe as Literature' has enjoyed an enthusiastic reception since its publication in 1985 . Reviewed in a wide array of scholarly journals and even in the popular press, the book has won praise nearly everywhere and has already earned for Nehamas--at least in the intellectual community at large--the reputation as the preeminent American Nietzsche scholar. At least two features of the book may help explain this phenomenon. First, Nehamas's Nietzsche is an imaginative synthesis of several important currents in recent Nietzsche commentary, reflecting the influence of writers like Jacques Der- rida, Sarah Kofman, Paul De Man, and Richard Rorty. These authors figure, often by name, throughout Nehamas's book; and it is perhaps Nehamas's most important achievement to have offered a reading of Nietzsche that incorporates the insights of these writers while surpassing them all in the philosophical ingenuity with which this style of interpreting Nietzsche is developed. The high profile that many of these thinkers now enjoy on the intellectual landscape accounts in part for the reception accorded the "Nietzsche" they so deeply influenced. -

Nietzsche and Psychedelics – Peter Sjöstedt-H –

Antichrist Psychonaut: Nietzsche and Psychedelics – Peter Sjöstedt-H – ‘… And close your eyes with holy dread, For he on honey-dew hath fed, And drunk the milk of Paradise.’ So ends the famous fragment of Kubla Khan by the Romantic poet, Samuel Taylor Coleridge. He tells us that the poem was an immediate transcription of an opium-induced dream he experienced in 1797. As is known, the Romantic poets and their kin were inspired by the use of psychoactive substances such as opium, the old world’s common pain reliever. Pain elimination is its negative advantage, but its positive attribute lies in the psychedelic (‘mind- revealing’)1 state it can engender – a state described no better than by the original English opium eater himself, Thomas De Quincey: O just and righteous opium! … thou bildest upon the bosom of darkness, out of the fantastic imagery of the brain, cities and temples, beyond the art of Phidias and Praxiteles – beyond the splendours of Babylon and Hekatómpylos; and, “from the anarchy of dreaming sleep,” callest into sunny light the faces of long-buried beauties … thou hast the keys of Paradise, O just, subtle, and mighty opium!2 Two decades following the publication of these words the First Opium War commences (1839) in which China is martially punished for trying to hinder the British trade of opium to the Chinese people. Though opium, derived from the innocent garden poppy Papavar somniferum, may cradle the keys to Paradise it also clutches the keys to Perdition: its addictive thus potentially ruinous nature is commonly known. Today, partly for these reasons, opiates are mostly illegal without license – stringently so in their most potent forms of morphine and heroin. -

Philosophy and Critical Theory

STANFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS PHILOSOPHY AND CRITICAL THEORY 20% DISCOUNT ON ALL TITLES 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS The Complete Works of Friedrich Nietzsche .......... 2-3 Political Philosophy ................ 3-5 Ethics and Moral Philosophy ..................................5-6 Phenomenology and Critical Theory ..........................6-8 Meridian: Crossing Aesthetics ...................................8-9 Cultural Memory in the Present .................................9-11 Now in Paperback ....................... 11 Examination Copy Policy ........ 11 The Case of Wagner / Unpublished Fragments ORDERING Twilight of the Idols / from the Period of Human, Use code S21PHIL to receive a 20% discount on all ISBNs The Antichrist / Ecce Homo All Too Human I (Winter listed in this catalog. / Dionysus Dithyrambs / 1874/75–Winter 1877/78) Visit sup.org to order online. Visit Nietzsche Contra Wagner Volume 12 sup.org/help/orderingbyphone/ Volume 9 Friedrich Nietzsche for information on phone Translated, with an Afterword, orders. Books not yet published Friedrich Nietzsche Edited by Alan D. Schrift, by Gary Handwerk or temporarily out of stock will be Translated by Adrian Del Caro, Carol charged to your credit card when This volume presents the first English Diethe, Duncan Large, George H. they become available and are in Leiner, Paul S. Loeb, Alan D. Schrift, translations of Nietzsche’s unpublished the process of being shipped. David F. Tinsley, and Mirko Wittwar notebooks from the years in which he developed the mixed aphoristic- The year 1888 marked the last year EXAMINATION COPY POLICY essayistic mode that continued across of Friedrich Nietzsche’s intellectual the rest of his career. These notebooks Examination copies of select titles career and the culmination of his comprise a range of materials, includ- are available on sup.org. -

BY PLATO• ARISTOTLE • .AND AQUINAS I

i / REF1,l!;CTit.>NS ON ECONOMIC PROBLEMS / BY PLATO• ARISTOTLE • .AND AQUINAS ii ~FLECTIONS ON ECONO:MIC PROBLEMS 1 BY PLA'I'O, ARISTOTLE, JJJD AQUINAS, By EUGENE LAIDIBEL ,,SWEARINGEN Bachelor of Science Oklahoma Agricultural and Mechanical Collage Stillwater, Oklahoma 1941 Submitted to the Depertmeut of Economics Oklahoma Agricultural and Mechanical College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE 1948 iii f.. 'I. I ···· i·: ,\ H.: :. :· ··: ! • • ~ ' , ~ • • !·:.· : i_ ·, 1r 1i1. cr~~rJ3t L l: i{ ,\ I~ Y , '•T •)() 1 0 ,1 8 API-'HOV~D BY: .J ,.· 1.., J l.;"t .. ---- -··- - ·- ______.,.. I 7 -.. JI J ~ L / \ l v·~~ u ' ~) (;_,LA { 7 {- ' r ~ (\.7 __\ _. ...A'_ ..;f_ ../-_" ...._!)_.... ..." ___ ......._ ·;...;;; ··-----/ 1--.,i-----' ~-.._.._ :_..(__,,---- ....... Member of the Report Committee 1..j lj:,;7 (\ - . "'·- -· _ .,. ·--'--C. r, .~-}, .~- Q_ · -~ Q.- 1Head of the Department . · ~ Dean of the Graduate School 502 04 0 .~ -,. iv . r l Preface The purpose and plan of this report are set out in the Introduction. Here, I only wish to express my gratitude to Professor Russell H. Baugh who has helped me greatly in the preparation of this report by discussing the various subjects as they were in the process of being prepared. I am very much indebted to Dr. Harold D. Hantz for his commentaries on the report and for the inspiration which his classes in Philosophy have furnished me as I attempted to correlate some of the material found in these two fields, Ecor!.Omics and Philosophy. I should like also to acknowledge that I owe my first introduction into the relationships of Economics and Philosophy to Dean Raymond Thomas, and his com~ents on this report have been of great value. -

Modernism 1 Modernism

Modernism 1 Modernism Modernism, in its broadest definition, is modern thought, character, or practice. More specifically, the term describes the modernist movement, its set of cultural tendencies and array of associated cultural movements, originally arising from wide-scale and far-reaching changes to Western society in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Modernism was a revolt against the conservative values of realism.[2] [3] [4] Arguably the most paradigmatic motive of modernism is the rejection of tradition and its reprise, incorporation, rewriting, recapitulation, revision and parody in new forms.[5] [6] [7] Modernism rejected the lingering certainty of Enlightenment thinking and also rejected the existence of a compassionate, all-powerful Creator God.[8] [9] In general, the term modernism encompasses the activities and output of those who felt the "traditional" forms of art, architecture, literature, religious faith, social organization and daily life were becoming outdated in the new economic, social, and political conditions of an Hans Hofmann, "The Gate", 1959–1960, emerging fully industrialized world. The poet Ezra Pound's 1934 collection: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. injunction to "Make it new!" was paradigmatic of the movement's Hofmann was renowned not only as an artist but approach towards the obsolete. Another paradigmatic exhortation was also as a teacher of art, and a modernist theorist articulated by philosopher and composer Theodor Adorno, who, in the both in his native Germany and later in the U.S. During the 1930s in New York and California he 1940s, challenged conventional surface coherence and appearance of introduced modernism and modernist theories to [10] harmony typical of the rationality of Enlightenment thinking. -

Outline of a Sociological Theory of Art Perception∗

From: Pierre Bordieu The Field of Cultural Production: Essays on Art and Literature ©1984, Columbia University Press Part III: The Pure Gaze: Essays on Art, Chapter 8 Outline of a Sociological Theory of Art Perception∗ PIERRE BOURDIEU 1 Any art perception involves a conscious or unconscious deciphering operation. 1.1 An act of deciphering unrecognized as such, immediate and adequate ‘comprehension’, is possible and effective only in the special case in which the cultural code which makes the act of deciphering possible is immediately and completely mastered by the observer (in the form of cultivated ability or inclination) and merges with the cultural code which has rendered the work perceived possible. Erwin Panofsky observes that in Rogier van der Weyden’s painting The Three Magi we immediately perceive the representation of an apparition’ that of a child in whom we recognize ‘the Infant Jesus’. How do we know that this is an apparition? The halo of golden rays surrounding the child would not in itself be sufficient proof, because it is also found in representations of the nativity in which the Infant Jesus is ‘real’. We come to this conclusion because the child is hovering in mid-air without visible support, and we do so although the representation would scarcely have been different had the child been sitting on a pillow (as in the case of the model which Rogier van der Weyden probably used). But one can think of hundreds of pictures in which human beings, animals or inanimate objects appear to be hovering in mid-air, contrary to the law of gravity, yet without giving the impression of being apparitions. -

Chapter 12. the Avant-Garde in the Late 20Th Century 1

Chapter 12. The Avant-Garde in the Late 20th Century 1 The Avant-Garde in the Late 20th Century: Modernism becomes Postmodernism A college student walks across campus in 1960. She has just left her room in the sorority house and is on her way to the art building. She is dressed for class, in carefully coordinated clothes that were all purchased from the same company: a crisp white shirt embroidered with her initials, a cardigan sweater in Kelly green wool, and a pleated skirt, also Kelly green, that reaches right to her knees. On her feet, she wears brown loafers and white socks. She carries a neatly packed bag, filled with freshly washed clothes: pants and a big work shirt for her painting class this morning; and shorts, a T-shirt and tennis shoes for her gym class later in the day. She’s walking rather rapidly, because she’s dying for a cigarette and knows that proper sorority girls don’t ever smoke unless they have a roof over their heads. She can’t wait to get into her painting class and light up. Following all the rules of the sorority is sometimes a drag, but it’s a lot better than living in the dormitory, where girls have ten o’clock curfews on weekdays and have to be in by midnight on weekends. (Of course, the guys don’t have curfews, but that’s just the way it is.) Anyway, it’s well known that most of the girls in her sorority marry well, and she can’t imagine anything she’d rather do after college. -

Philosophy of Science -----Paulk

PHILOSOPHY OF SCIENCE -----PAULK. FEYERABEND----- However, it has also a quite decisive role in building the new science and in defending new theories against their well-entrenched predecessors. For example, this philosophy plays a most important part in the arguments about the Copernican system, in the development of optics, and in the Philosophy ofScience: A Subject with construction of a new and non-Aristotelian dynamics. Almost every work of Galileo is a mixture of philosophical, mathematical, and physical prin~ a Great Past ciples which collaborate intimately without giving the impression of in coherence. This is the heroic time of the scientific philosophy. The new philosophy is not content just to mirror a science that develops independ ently of it; nor is it so distant as to deal just with alternative philosophies. It plays an essential role in building up the new science that was to replace 1. While it should be possible, in a free society, to introduce, to ex the earlier doctrines.1 pound, to make propaganda for any subject, however absurd and however 3. Now it is interesting to see how this active and critical philosophy is immoral, to publish books and articles, to give lectures on any topic, it gradually replaced by a more conservative creed, how the new creed gener must also be possible to examine what is being expounded by reference, ates technical problems of its own which are in no way related to specific not to the internal standards of the subject (which may be but the method scientific problems (Hurne), and how there arises a special subject that according to which a particular madness is being pursued), but to stan codifies science without acting back on it (Kant). -

Dialectical Materialism and Subject: Monism and Dialectic

経済学論纂(中央大学)第57巻第 3 ・ 4 合併号(2017年 3 月) 243 Dialectical Materialism and Subject: Monism and Dialectic Hideki Shibata Introduction Chapter 1 Critique of Tadashi Kato Chapter 2 Sartre’s Theory of Subject Chapter 3 Language and Subject: the Social Origin of Transcendental Beings Conclusion Introduction I have translated three of Tadashi Kato’s articles (Kato 2014; Kato 2015; Kato 2016). In these articles, Kato seizes Marx’s monistic argument, but divides dialectics into the dialectic of cognition and the dialectic of objects, and finally turns to the dualism of cognition and the objective world because of Engels’ influence. Hegel’s dialectic was born as the identity of substance and subject (substance is subject) in its birthplace, the Phenomenology of Spirit, but this means the identity of being and cogni- tion.1) It does not mean that there are two kinds of dialectic. To overcome the dualism that remained after Kant was one of the principle themes of German Idealist Philosophy, and Marx also inherited this critically important issue. Marx’s monism, however, does not mean that “we must understand man as a being who produces himself and his world” (Landgrebe 1966, p. 10). Marx’s monism does not character- ize the world as the product of the constitutive operations of the human subject. Sartre un- derstood Marx’s real intention, and developed it in his articles (Cf. Omote 2014). In the con- clusion of Transcendence of the Ego, Sartre writes, “a working hypothesis as fruitful as historical materialism,” and follows it with a criticism of Engels’ materialism, which “never This paper owes much to the thoughtful and helpful comments and advices of the editor of Editage(by Cactus Communications). -

MF-Romanticism .Pdf

Europe and America, 1800 to 1870 1 Napoleonic Europe 1800-1815 2 3 Goals • Discuss Romanticism as an artistic style. Name some of its frequently occurring subject matter as well as its stylistic qualities. • Compare and contrast Neoclassicism and Romanticism. • Examine reasons for the broad range of subject matter, from portraits and landscape to mythology and history. • Discuss initial reaction by artists and the public to the new art medium known as photography 4 30.1 From Neoclassicism to Romanticism • Understand the philosophical and stylistic differences between Neoclassicism and Romanticism. • Examine the growing interest in the exotic, the erotic, the landscape, and fictional narrative as subject matter. • Understand the mixture of classical form and Romantic themes, and the debates about the nature of art in the 19th century. • Identify artists and architects of the period and their works. 5 Neoclassicism in Napoleonic France • Understand reasons why Neoclassicism remained the preferred style during the Napoleonic period • Recall Neoclassical artists of the Napoleonic period and how they served the Empire 6 Figure 30-2 JACQUES-LOUIS DAVID, Coronation of Napoleon, 1805–1808. Oil on canvas, 20’ 4 1/2” x 32’ 1 3/4”. Louvre, Paris. 7 Figure 29-23 JACQUES-LOUIS DAVID, Oath of the Horatii, 1784. Oil on canvas, approx. 10’ 10” x 13’ 11”. Louvre, Paris. 8 Figure 30-3 PIERRE VIGNON, La Madeleine, Paris, France, 1807–1842. 9 Figure 30-4 ANTONIO CANOVA, Pauline Borghese as Venus, 1808. Marble, 6’ 7” long. Galleria Borghese, Rome. 10 Foreshadowing Romanticism • Notice how David’s students retained Neoclassical features in their paintings • Realize that some of David’s students began to include subject matter and stylistic features that foreshadowed Romanticism 11 Figure 30-5 ANTOINE-JEAN GROS, Napoleon at the Pesthouse at Jaffa, 1804. -

Aristotle's Subject Matter Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment Of

Aristotle’s Subject Matter Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University Keren Wilson Shatalov, MLitt Graduate Program in Philosophy The Ohio State University 2019 Dissertation Committee: Allan Silverman, Adviser Tamar Rudavsky Lisa Downing ii Copyright by Keren Wilson Shatalov 2019 iii Abstract In my dissertation I examine Aristotle’s concept of matter by highlighting the tools from his Organon which he uses to introduce matter in his Physics. I make use of logical concepts Aristotle develops in his work on explanation in Posterior Analytics, especially his concept of subject or ὑποκείμενον, to argue that matter, for Aristotle, must be understood not as a distinct ontological category but as a term of art denoting a part of an explanation in natural philosophy. By presenting an analysis of Aristotle’s concept of ὑποκείμενον from his logical works, I show how Aristotle uses it to spell out just what explanatory role matter plays, and what this means for what it is to be matter. I argue that when Aristotle uses the term “ὑποκείμενον” to name a principle of change in Physics A, he is employing the logical concept which he had made use of and developed in his logical works, contra prominent readings which argue instead that the term in Physics is a distinct technical term, homonymous with the logical term. Further, I offer a new reading of the concept of ὑποκείμενον in the logical works. On my reading, a genuine ὑποκείμενον is something which, just by being what it is or ὅπερ x τι, is what is presupposed by something else, y, and which grounds and partially explains the presence of that y. -

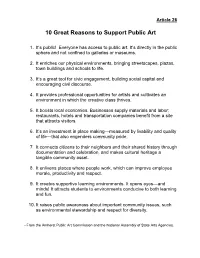

10 Great Reasons to Support Public Art

Article 26 10 Great Reasons to Support Public Art 1. It’s public! Everyone has access to public art. It’s directly in the public sphere and not confined to galleries or museums. 2. It enriches our physical environments, bringing streetscapes, plazas, town buildings and schools to life. 3. It’s a great tool for civic engagement, building social capital and encouraging civil discourse. 4. It provides professional opportunities for artists and cultivates an environment in which the creative class thrives. 5. It boosts local economies. Businesses supply materials and labor; restaurants, hotels and transportation companies benefit from a site that attracts visitors. 6. It’s an investment in place making—measured by livability and quality of life—that also engenders community pride. 7. It connects citizens to their neighbors and their shared history through documentation and celebration, and makes cultural heritage a tangible community asset. 8. It enlivens places where people work, which can improve employee morale, productivity and respect. 9. It creates supportive learning environments. It opens eyes—and minds! It attracts students to environments conducive to both learning and fun. 10. It raises public awareness about important community issues, such as environmental stewardship and respect for diversity. --From the Amherst Public Art Commission and the National Assembly of State Arts Agencies. The Amherst Public Art Commission Why Public Art for Amherst? Public art adds enormous value to the cultural, aesthetic and economic vitality of a community. It is now a well-accepted principle of urban design that public art contributes to a community’s identity, fosters community pride and a sense of belonging, and enhances the quality of life for its residents and visitors.