Raven Steals The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Broadcasting Decision CRTC 2005-393

Broadcasting Decision CRTC 2005-393 Ottawa, 11 August 2005 The Haliburton Broadcasting Group Inc. North Bay, Ontario Application 2004-0418-7 Public Hearing in the National Capital Region 16 May 2005 English-language FM radio station in North Bay The Commission approves an application by The Haliburton Broadcasting Group Inc. for a broadcasting licence to operate an English-language FM radio station in North Bay, Ontario. Introduction 1. In Call for applications for broadcasting licences to carry on radio programming undertakings to serve North Bay, Ontario, Broadcasting Public Notice CRTC 2004-69, 15 September 2004, the Commission announced that it had received an application for a broadcasting licence to provide a commercial radio service to North Bay, Ontario. Consistent with the procedures generally followed by the Commission in such cases, it called for applications from other parties wishing to obtain a broadcasting licence to serve the North Bay radio market. Subsequently, in Broadcasting Notice of Public Hearing CRTC 2005-3, 17 March 2005, the Commission announced that it would consider two applications, one by The Haliburton Broadcasting Group Inc. (Haliburton) and the other by Eternacom Inc. (Eternacom), for new English-language commercial radio stations to serve North Bay at a public hearing held in the National Capital Region commencing 16 May 2005. The application 2. Haliburton requested a broadcasting licence to operate a new English-language FM commercial radio programming undertaking in North Bay at 106.3 MHz (channel 292B1) with an effective radiated power (ERP) of 10,000 watts. Interventions 3. The Commission received many interventions in support of this application, and an intervention in opposition by Muskoka-Parry Sound Broadcasting Limited (MPS), the licensee of CFBK-FM Huntsville, Ontario. -

Stations Monitored

Stations Monitored 10/01/2019 Format Call Letters Market Station Name Adult Contemporary WHBC-FM AKRON, OH MIX 94.1 Adult Contemporary WKDD-FM AKRON, OH 98.1 WKDD Adult Contemporary WRVE-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 99.5 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WYJB-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY B95.5 Adult Contemporary KDRF-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 103.3 eD FM Adult Contemporary KMGA-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 99.5 MAGIC FM Adult Contemporary KPEK-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 100.3 THE PEAK Adult Contemporary WLEV-FM ALLENTOWN-BETHLEHEM, PA 100.7 WLEV Adult Contemporary KMVN-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MOViN 105.7 Adult Contemporary KMXS-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MIX 103.1 Adult Contemporary WOXL-FS ASHEVILLE, NC MIX 96.5 Adult Contemporary WSB-FM ATLANTA, GA B98.5 Adult Contemporary WSTR-FM ATLANTA, GA STAR 94.1 Adult Contemporary WFPG-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ LITE ROCK 96.9 Adult Contemporary WSJO-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ SOJO 104.9 Adult Contemporary KAMX-FM AUSTIN, TX MIX 94.7 Adult Contemporary KBPA-FM AUSTIN, TX 103.5 BOB FM Adult Contemporary KKMJ-FM AUSTIN, TX MAJIC 95.5 Adult Contemporary WLIF-FM BALTIMORE, MD TODAY'S 101.9 Adult Contemporary WQSR-FM BALTIMORE, MD 102.7 JACK FM Adult Contemporary WWMX-FM BALTIMORE, MD MIX 106.5 Adult Contemporary KRVE-FM BATON ROUGE, LA 96.1 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WMJY-FS BILOXI-GULFPORT-PASCAGOULA, MS MAGIC 93.7 Adult Contemporary WMJJ-FM BIRMINGHAM, AL MAGIC 96 Adult Contemporary KCIX-FM BOISE, ID MIX 106 Adult Contemporary KXLT-FM BOISE, ID LITE 107.9 Adult Contemporary WMJX-FM BOSTON, MA MAGIC 106.7 Adult Contemporary WWBX-FM -

P>20 January 2020 Filed Online Via Gckey

20 January 2020 Filed online via GCKey Claude Doucet Secretary General CRTC Ottawa, ON K1A 0N2 Dear Secretary General, Re: Part 1 licence renewal applications submitted by Rogers Media Inc.: 2019-0901-1, 2019-0913-6, 2019-0923-5, 2019-0903-7, 2019-0915-2, 2019-0926-9, 2019-0906-1, 2019-0919-4, 2019-0927-7, 2019-0907-9, 2019-0920-2, 2019-0929-3, 2019-0910-3, 2019-0936-8, 2019-0935-0, 2019-0911-0 1 The Forum for Research and Policy in Communications (FRPC) is a non-profit and non- partisan organization established to undertake research and policy analysis about electronic communications, including broadcasting. 2 We are writing with respect to the Part I radio licence renewal applications submitted in early December 2019 by Rogers Media Inc.; our intervention is attached. 3 Should the CRTC decide to hold a public hearing with respect to these applications the Forum requests the opportunity to appear. Sincerely yours, Monica. L. Auer, M.A., LL.M. Executive Director Forum for Research and Policy in Communications (FRPC) Ottawa, Ontario cc.: Susan Wheeler, [email protected]; [email protected] Vice-President Regulatory, Media Rogers Media Inc. Part 1 applications to renew radio licences Intervention(20 January 2020) Contents Contents Executive summary 1 I. Introduction 1 A. Current requirements for commercial radio stations in Canada 1 1. The Broadcasting Act 1 2. Regulations that apply to broadcasting applications 3 3. Commercial radio policy 5 B. Evidentiary gap by CRTC in this licence renewal process 7 II. Rogers and its applications 8 III. -

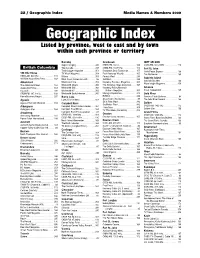

Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by Province, West to East and by Town Within Each Province Or Territory

22 / Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by province, west to east and by town within each province or territory Burnaby Cranbrook fORT nELSON Super Camping . 345 CHDR-FM, 102.9 . 109 CKRX-FM, 102.3 MHz. 113 British Columbia Tow Canada. 349 CHBZ-FM, 104.7mHz. 112 Fort St. John Truck Logger magazine . 351 Cranbrook Daily Townsman. 155 North Peace Express . 168 100 Mile House TV Week Magazine . 354 East Kootenay Weekly . 165 The Northerner . 169 CKBX-AM, 840 kHz . 111 Waters . 358 Forests West. 289 Gabriola Island 100 Mile House Free Press . 169 West Coast Cablevision Ltd.. 86 GolfWest . 293 Gabriola Sounder . 166 WestCoast Line . 359 Kootenay Business Magazine . 305 Abbotsford WaveLength Magazine . 359 The Abbotsford News. 164 Westworld Alberta . 360 The Kootenay News Advertiser. 167 Abbotsford Times . 164 Westworld (BC) . 360 Kootenay Rocky Mountain Gibsons Cascade . 235 Westworld BC . 360 Visitor’s Magazine . 305 Coast Independent . 165 CFSR-FM, 107.1 mHz . 108 Westworld Saskatchewan. 360 Mining & Exploration . 313 Gold River Home Business Report . 297 Burns Lake RVWest . 338 Conuma Cable Systems . 84 Agassiz Lakes District News. 167 Shaw Cable (Cranbrook) . 85 The Gold River Record . 166 Agassiz/Harrison Observer . 164 Ski & Ride West . 342 Golden Campbell River SnoRiders West . 342 Aldergrove Campbell River Courier-Islander . 164 CKGR-AM, 1400 kHz . 112 Transitions . 350 Golden Star . 166 Aldergrove Star. 164 Campbell River Mirror . 164 TV This Week (Cranbrook) . 352 Armstrong Campbell River TV Association . 83 Grand Forks CFWB-AM, 1490 kHz . 109 Creston CKGF-AM, 1340 kHz. 112 Armstrong Advertiser . 164 Creston Valley Advance. -

530 CIAO BRAMPTON on ETHNIC AM 530 N43 35 20 W079 52 54 09-Feb

frequency callsign city format identification slogan latitude longitude last change in listing kHz d m s d m s (yy-mmm) 530 CIAO BRAMPTON ON ETHNIC AM 530 N43 35 20 W079 52 54 09-Feb 540 CBKO COAL HARBOUR BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N50 36 4 W127 34 23 09-May 540 CBXQ # UCLUELET BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 56 44 W125 33 7 16-Oct 540 CBYW WELLS BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N53 6 25 W121 32 46 09-May 540 CBT GRAND FALLS NL VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 57 3 W055 37 34 00-Jul 540 CBMM # SENNETERRE QC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 22 42 W077 13 28 18-Feb 540 CBK REGINA SK VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N51 40 48 W105 26 49 00-Jul 540 WASG DAPHNE AL BLK GSPL/RELIGION N30 44 44 W088 5 40 17-Sep 540 KRXA CARMEL VALLEY CA SPANISH RELIGION EL SEMBRADOR RADIO N36 39 36 W121 32 29 14-Aug 540 KVIP REDDING CA RELIGION SRN VERY INSPIRING N40 37 25 W122 16 49 09-Dec 540 WFLF PINE HILLS FL TALK FOX NEWSRADIO 93.1 N28 22 52 W081 47 31 18-Oct 540 WDAK COLUMBUS GA NEWS/TALK FOX NEWSRADIO 540 N32 25 58 W084 57 2 13-Dec 540 KWMT FORT DODGE IA C&W FOX TRUE COUNTRY N42 29 45 W094 12 27 13-Dec 540 KMLB MONROE LA NEWS/TALK/SPORTS ABC NEWSTALK 105.7&540 N32 32 36 W092 10 45 19-Jan 540 WGOP POCOMOKE CITY MD EZL/OLDIES N38 3 11 W075 34 11 18-Oct 540 WXYG SAUK RAPIDS MN CLASSIC ROCK THE GOAT N45 36 18 W094 8 21 17-May 540 KNMX LAS VEGAS NM SPANISH VARIETY NBC K NEW MEXICO N35 34 25 W105 10 17 13-Nov 540 WBWD ISLIP NY SOUTH ASIAN BOLLY 540 N40 45 4 W073 12 52 18-Dec 540 WRGC SYLVA NC VARIETY NBC THE RIVER N35 23 35 W083 11 38 18-Jun 540 WETC # WENDELL-ZEBULON NC RELIGION EWTN DEVINE MERCY R. -

Ownership Charts Reflect the Transactions Approved by the Commission and Are Based on Information Supplied by Licensees

ROGERS Radio, TV, Network & Satellite-to-Cable #27b Ownership – Broadcasting - CRTC 2021-03-29 UPDATE Administrative Decision – 2017-04-28 – approved a 2 step transaction involving 8384886 Canada Inc. (8384886) and resulting in 1) change in ownership of 8384886 through the transfer of all of its shares from Newcap Inc. to its wholly owned subsidiary, 8384860 Canada Inc. and; 2) change in ownership and effective control of 8384886 through the transfer of all of its issued and outstanding shares to Rogers Media Inc. (2017-0260-6 & 2017-0275-4) CRTC 2017-251 – approved a change in ownership and effective control of Tillsonburg Broadcasting Company Limited through the transfer to Rogers Media Inc. of all of the issued and outstanding shares in the share capital of Lamers Holdings Inc. Amalgamation – 2018-01-01 – de Rogers Media Inc., Tillsonburg Broadcasting Company Limited, 8384886 Canada Inc. and 10538850 Canada Inc. (formerly Lamers Holdings Inc.), to continue as Rogers Media Inc. CRTC 2018-227 – approved the acquision by Rogers Media Inc. of the assets of CJCY-FM Medicine Hat from Clear Sky Radio Inc. Update – 2020-05-28 – minor change. CRTC 2020-389 – approved the acquisition by Akash Broadcasting Inc. of the assets of CKER-FM Edmonton from Rogers Media Inc. Note: The transaction closed on 1 January 2021. SEE ALSO 27, 27A and 27C NOTICE The CRTC ownership charts reflect the transactions approved by the Commission and are based on information supplied by licensees. The CRTC does not assume any responsibility for discrepancies between its charts and data from outside sources or for errors or omissions which they may contain. -

Federation of Ontario Naturalists Radio

RADIO AS A VEHICLE FOR INFORMED ENVIRONMENTAL COMMENTARY - A FEASIBILITY STUDY A project proposal submitted by the Canadian Environmental Law Research Foundation and Federation of Ontario Naturalists April, 1984 CIELAP Shelf: Canadian Environmental Law Research Foundation; Federation of Ontario Naturalists Radio as a Vehicle for Informed Environmental Commentary - A Feasibility Study RN 27318 RADIO AS A VEHICLE FOR INFORMED ENVIRONMENTAL COMMENTARY A FEASIBILITY STUDY TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. The need for informed commentary 1 2. Why radio' 3 3. Study objectives 4 4. The study 5 5. Workplan 8 6. Timeline 9 7. Budget 10 8. The study team 11 9. The Canadian Environmental Law Research Foundation 35 10. The Federation of Ontario Naturalists 37 11. Appendices A) CJRT - FM Open College 48 B) The pilot programs 53 C) List of stations to be approached 57 D) Questionnaire 73 E) Letters of support 76 - 1 - THE NEED FOR INFORMED COMMENTARY The Canadian Environmental Law Research Foundation and Federation of Ontario Naturalists are pleased to submit this proposal for a study of the feasibility of producing a regular weekly radio program which would provide Ontario listeners with informed and relevant discussion of current environmental issues. Environmental problems continue to worsen - toxic chemicals increasingly threaten drinking water sources, acid rain is killing more and more northern lakes, while environmental contamination in the home and work place is a source of growing concern. Public reaction in the face of these mounting problems can be characterized by two words - concern and confusion. Public opinion polls show that Canadians believe strongly in the need for environmental protection. -

Get Maximum Exposure to the Largest Number of Professionals in The

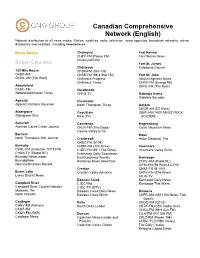

Canadian Comprehensive Network (English) National distribution to all news media. Dailies, weeklies, radio, television, news agencies, broadcast networks, online databases and websites, including newswire.ca. News Media Chetwynd Fort Nelson CHET-FM [Peace FM] Fort Nelson News Chetwynd Echo British Columbia Fort St. James Chilliwack Caledonia Courier 100 Mile House CFSR-FM (Star FM) CKBX-AM CKSR-FM (98.3 Star FM) Fort St. John CKWL-AM [The Wolf] Chilliwack Progress Alaska Highway News Chilliwack Times CHRX-FM (Energy 98) Abbotsford CKNL-FM (The Bear) CKQC-FM Clearbrook Abbotsford/Mission Times CFEG-TV Gabriola Island Gabriola Sounder Agassiz Clearwater Agassiz Harrison Observer North Thompson Times Golden CKGR-AM [EZ Rock] Aldergrove Coquitlam CKIR-AM [1400 AM EZ ROCK Aldergrove Star Now, The GOLDEN] Ashcroft Courtenay Hagensborg Ashcroft Cache Creek Journal CKLR-FM (The Eagle) Coast Mountain News Comox Valley Echo Barriere Hope North Thompson Star Journal Cranbrook Hope Standard, The CHBZ-FM (B104) Burnaby CHDR-FM (The Drive) Invermere CFML-FM (Evolution 107.9 FM) CJDR-FM (99.1 The Drive) Invermere Valley Echo CHAN-TV (Global BC) Cranbrook Daily Townsman Burnaby NewsLeader East Kootenay Weekly Kamloops BurnabyNow Kootenay News Advertiser CHNL-AM (Radio NL) New Westminster Record CIFM-FM (98 Point 3 CIFM) Creston CKBZ-FM (B-100) Burns Lake Creston Valley Advance CKRV-FM (The River) Lakes District News CFJC-TV Dawson Creek Kamloops Daily News Campbell River CJDC-AM Kamloops This Week Campbell River Courier-Islander CJDC-TV (NTV) Midweek, -

Stations Monitored

Stations Monitored Call Letters Market Station Name Format WAPS-FM AKRON, OH 91.3 THE SUMMIT Triple A WHBC-FM AKRON, OH MIX 94.1 Adult Contemporary WKDD-FM AKRON, OH 98.1 WKDD Adult Contemporary WRQK-FM AKRON, OH ROCK 106.9 Mainstream Rock WONE-FM AKRON, OH 97.5 WONE THE HOME OF ROCK & ROLL Classic Rock WQMX-FM AKRON, OH FM 94.9 WQMX Country WDJQ-FM AKRON, OH Q 92 Top Forty WRVE-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 99.5 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WYJB-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY B95.5 Adult Contemporary WPYX-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY PYX 106 Classic Rock WGNA-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY COUNTRY 107.7 FM WGNA Country WKLI-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 100.9 THE CAT Country WEQX-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 102.7 FM EQX Alternative WAJZ-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY JAMZ 96.3 Top Forty WFLY-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY FLY 92.3 Top Forty WKKF-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY KISS 102.3 Top Forty KDRF-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 103.3 eD FM Adult Contemporary KMGA-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 99.5 MAGIC FM Adult Contemporary KPEK-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 100.3 THE PEAK Adult Contemporary KZRR-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM KZRR 94 ROCK Mainstream Rock KUNM-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM COMMUNITY RADIO 89.9 College Radio KIOT-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM COYOTE 102.5 Classic Rock KBQI-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM BIG I 107.9 Country KRST-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 92.3 NASH FM Country KTEG-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 104.1 THE EDGE Alternative KOAZ-AM ALBUQUERQUE, NM THE OASIS Smooth Jazz KLVO-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 97.7 LA INVASORA Latin KDLW-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM ZETA 106.3 Latin KKSS-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM KISS 97.3 FM -

2011 Radio PSA Nat'l Stn List.R3 Copy

RADIO PSA DISTRIBUTION April 2012 Ontario-Only (Eng Fre) Staon Vernacular Lang Type Format City Prov Owner,Firm Phone Number CHLK-FM Lake 88.1 E FM Music; News; Pop Music Perth ONT (Perkin) Brian & Norm Wright +1 (613) 264-8811 CFWC-FM E FM Music; News; ChrisPan Music BranQord ONT 1486781 ONT Limited +1 (519) 759-2339 CKAV-FM Aboriginal Voices Radio E FM Music; News Toronto ONT Aboriginal Voices Radio Inc. +1 (416) 703-1287 CJRN-AM CJRN E AM Music; News Niagara Falls ONT AM 710 Radio Inc. (905) 356.6710 Ext.231 CJAI-FM Amherst Island Public Radio E FM Music; News Stella ONT Amherst Island Public Radio +1 (613) 384-8282 CHAM-AM 820 CHAM E AM Country, Folk, Bluegrass; Music; News; Sports Hamilton ONT Astral Media +1 (905) 574-1150 Ext. 421 CKLH-FM 102.9 K-Lite FM E FM Music; News CKOC-AM Oldies 1150 AM Music; News; Oldies CIQM-FM 97-5 London's EZ Rock E FM Music; News; Pop Music CJBK-AM News Talk 1290 CJBK E AM News; Sports London ONT Astral Media +1 (519) 686-6397 CKSL-AM Funny 1410 E AM Music; News; Oldies CJBX-FM News Talk 1290 CJBK E FM Country, Folk, Bluegrass; London ONT Astral Media +1 (519) 691-2403 Music; News CJOT-FM Boom 99.7 E FM Music; News; Rock Music Oawa ONT Astral Media +1 (613) 225-1069 Ext. 271 CKQB-FM 106-9 The Bear E FM Music; News; Rock Music Oawa ONT Astral Media +1 (613) 225-1069 CHVR-FM Star 96 E FM Country, Folk, Bluegrass; Pembroke ONT Astral Media +1 (613) 735-9670 Ext. -

Findings Regarding Market Capacity and the Appropriateness of Issuing a Call for Radio Applications to Serve North Bay

Broadcasting Decision CRTC 2019-200 PDF version Reference: 2018-380 Ottawa, 6 June 2019 Public record: 1011-NOC2018-0380 Findings regarding market capacity and the appropriateness of issuing a call for radio applications to serve North Bay The Commission finds that the market of North Bay, Ontario, can sustain an additional radio station at this time. Given that no other party besides Vista Radio Ltd. (Vista) expressed interest in serving this market, the Commission considers that it is not necessary to publish a call for applications. Accordingly, the Commission will publish the application filed by Vista for a broadcasting licence to operate a new commercial FM radio station in this market as part of the non-appearing phase of an upcoming public hearing. Introduction 1. In Broadcasting Notice of Consultation 2018-380, the Commission announced that it had received an application by Vista Radio Ltd. (Vista) for a broadcasting licence to operate a commercial radio station to serve North Bay, Ontario. 2. The city of North Bay is located in northeastern Ontario approximately 120 kilometres east of Sudbury. The North Bay radio market is currently served by four English-language commercial radio stations: CHUR-FM, CKFX-FM and CKAT, operated by Rogers Media Inc. (Rogers), as well as CFXN-FM, operated by Vista. The market is also served by the commercial specialty (Christian music) radio station CJTK-FM-1 (Harvest Ministries Sudbury), as well as a transmitter that rebroadcasts the programming of CBCS-FM Sudbury (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation). 3. In accordance with Broadcasting Regulatory Policy 2014-554 (the Policy), the Commission called for comments on the capacity of the North Bay market to support a new station and the appropriateness of issuing a call for applications for new stations in this market. -

Inside This Issue

News ● Serving DX’ers since 1933 Volume 78, No. 30 ● September 19, 2011 ● (ISSN 0737-1639) Inside this issue . 2 … AM Switch 20 … Geomagnetic Indices 32 … Confirmed Dxer 8 … Domestic DX Digest West 21 … DX Toolbox 33 … Index to Volume 78 14 … Domestic DX Digest East 23 … Musings of the Members 34 … NRC Contests 17 … International DX Digest 24 … Pro Sports Networks 35 … Convention 2011 Omaha 2011: Come join us for the joint VOL. 79 DX NEWS PUBLISHING SCHEDULE NRC/WTFDA Convention in Omaha from No In By Date No In By Date October 13 to 16. All the details are on page 35 – 1 Sept. 23 Oct. 3 16 Jan. 13 Jan. 23 but remember that the registration deadline is 2 Sept. 30 Oct. 10 17 Jan. 20 Jan. 30 October 1. This year’s convention will be 3 Oct. 7 Oct. 17 18 Jan. 27 Feb. 6 dedicated to the late Bruce Elving. 4 Oct. 14 Oct. 24 19 Feb. 3 Feb. 13 NRC AM Radio Log 32nd Edition: It’s out, 5 Oct. 21 Oct. 31 20 Feb. 10 Feb. 20 and looking great as usual. If you haven’t 6 Oct. 28 Nov. 7 21 Feb. 17 Feb. 27 ordered yours yet, do it today – no serious MW 7 Nov. 4 Nov. 14 22 Feb. 24 Mar. 5 DXer can be without it. Details below. 8 Nov. 11 Nov. 21 23 Mar. 2 Mar. 12 From the Publisher: We recently learned that 9 Nov. 18 Nov. 28 24 Mar. 16 Mar. 26 NRC member Jerry Keedy of Pine Bluff AR 10 Nov.