Balkan As a Metaphor in the Film Composition of Goran Bregovic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 4: (1960 – 1980) Branches of Čoček

Gundula Gruen Gundula Gruen MA Ethnomusicology MUM120: Ethnomusicology Major Project August 2018 Title: UNDERSTANDING ČOČEK – AN HISTORICAL, MUSICAL AND SOCIOLOGICAL EXPLORATION Module Tutor: Dr Laudan Nooshin Student Name: Gundula Gruen Student No: 160033648 Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MA in Ethnomusicology Total word count: 20,866 (including headings, excluding footnotes and references) TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ......................................................................................................................................... 7 Foreword: ...................................................................................................................................... 8 Acknowledgements: .................................................................................................................. 8 Definitions and Spellings .......................................................................................................... 8 Introduction: ................................................................................................................................ 11 Chapter 1: The Origins of Čoček ................................................................................................ 15 The History of Köçek in Ottoman Times ................................................................................ 16 Speculation on Older Roots of Čoček ..................................................................................... 18 Chapter 2: Čalgija -

VOLUME 1 • NUMBER 1 • 2018 Aims and Scope

VOLUME 1 • NUMBER 1 • 2018 Aims and Scope Critical Romani Studies is an international, interdisciplinary, peer-reviewed journal, providing a forum for activist-scholars to critically examine racial oppressions, different forms of exclusion, inequalities, and human rights abuses Editors of Roma. Without compromising academic standards of evidence collection and analysis, the Journal seeks to create a platform to critically engage with Maria Bogdan academic knowledge production, and generate critical academic and policy Central European University knowledge targeting – amongst others – scholars, activists, and policy-makers. Jekatyerina Dunajeva Pázmány Péter Catholic University Scholarly expertise is a tool, rather than the end, for critical analysis of social phenomena affecting Roma, contributing to the fight for social justice. The Journal Tímea Junghaus especially welcomes the cross-fertilization of Romani studies with the fields of European Roma Institute for Arts and Culture critical race studies, gender and sexuality studies, critical policy studies, diaspora studies, colonial studies, postcolonial studies, and studies of decolonization. Angéla Kóczé Central European University The Journal actively solicits papers from critically-minded young Romani Iulius Rostas (editor-in-chief) scholars who have historically experienced significant barriers in engaging Central European University with academic knowledge production. The Journal considers only previously unpublished manuscripts which present original, high-quality research. The Márton Rövid (managing editor) Journal is committed to the principle of open access, so articles are available free Central European University of charge. All published articles undergo rigorous peer review, based on initial Marek Szilvasi (review editor) editorial screening and refereeing by at least two anonymous scholars. The Journal Open Society Foundations provides a modest but fair remuneration for authors, editors, and reviewers. -

BULGARIA 2020 RODOPI MOUNTAINS CYCLE TOUR Semi-Guided - 8 Days/7 Nights

BULGARIA 2020 RODOPI MOUNTAINS CYCLE TOUR Semi-Guided - 8 Days/7 Nights The Rodopi Mountains are located in the oldest part of the Balkans with some of the loveliest coniferous forests in the country. The landscape is gentle and rolling, with gorges intermingling with river basins and valleys. Here one can also find 70% of the world minerals, as well as some 600 caves. Flora and fauna contain species that have become extinct in other European countries. Locals live a traditional way of life: wooden carts pulled by horses, donkeys or cows; nomadic gypsies picking mushrooms and berries in the woods; local Muslim inhabitants growing tobacco and potatoes; and herds of sheep and goats descending the mountain at day’s end. You will cycle through villages with typical Rodopean architecture where speech, songs and customs of the local people create the special identity of the region. You have the chance to visit Bachkovo Monastery, the second largest in Bulgaria; see the Miraculous bridges, two unique natural rock bridges about 40 m. high; Velingrad – the largest Bulgarian spa resort famous for its healing hot mineral water. ITINERARY Day 1. Arrive at Sofia or Plovdiv Airport and transfer to your hotel in Sofia. Day 2. Sofia– Belmeken Dam – Velingrad spa town Transfer to the cycling start a few kilometers before the village of Sestrimo. Cycle up to the Belmeken dam (2000 m) through old coniferous woods. In the afternoon the road passes the Iundola's mountain meadows before descending to the spa town of Velingrad, where you stay overnight in a hotel with mineral water swimming pool. -

Journal of Writing and Writing Courses

TEXT creative TEXT Journal of writing and writing courses ISSN: 1327-9556 | https://www.textjournal.com.au/ TEXT creative Contents page Poetry Richard James Allen, Click here to allow this poem to access your location Gayelene Carbis, Oranges Edward Caruso, Potsherds Becky Cherriman, Christina Tissues a Script (or what my Otter app misheard) Abigail Fisher, A un poema acerca del agua Carolyn Gerrish, Aperture Lauren Rae, Hemispheric March Script Cailean McBride, Be Near Me (after In Memoriam) Prose Julia Prendergast, Mothwebs, spinners, orange Patrick West, Pauline Laura Grace Simpkins, Vanilla Phillip Edmonds, Giving it away Rosanna Licari, Fiona and the fish Georgia Rose Phillips, On the Obfuscations of Language Diane Stubbings, From Variation for three voices on a letter to nature Ariel Riveros, Planetary Nephology Calendar App Dean Kerrison, 2 stories Lachie Rhodes, The Silver Locket Tara East, Story Monster Ned Brooks, This is Not a Film TEXT Vol 24 No 2 October 2020 www.textjournal.com.au General editor: Nigel Krauth. Creative works editor: Anthony Lawrence TEXT poetry Richard James Allen Click here to allow this poem to access your location TEXT Journal of writing and writing courses ISSN: 1327-9556 | https://www.textjournal.com.au/ TEXT poetry Richard James Allen Click here to allow this poem to access your location I couldn’t lasso it but I drew a line from there to here and swung between [Michigan] and the moon. Richard James Allen is an Australian born poet. His latest book is The short story of you and I (UWAP, 2019). His writing has appeared widely in journals, anthologies, and online over many years. -

Annex REPORT for 2019 UNDER the “HEALTH CARE” PRIORITY of the NATIONAL ROMA INTEGRATION STRATEGY of the REPUBLIC of BULGAR

Annex REPORT FOR 2019 UNDER THE “HEALTH CARE” PRIORITY of the NATIONAL ROMA INTEGRATION STRATEGY OF THE REPUBLIC OF BULGARIA 2012 - 2020 Operational objective: A national monitoring progress report has been prepared for implementation of Measure 1.1.2. “Performing obstetric and gynaecological examinations with mobile offices in settlements with compact Roma population”. During the period 01.07—20.11.2019, a total of 2,261 prophylactic medical examinations were carried out with the four mobile gynaecological offices to uninsured persons of Roma origin and to persons with difficult access to medical facilities, as 951 women were diagnosed with diseases. The implementation of the activity for each Regional Health Inspectorate is in accordance with an order of the Minister of Health to carry out not less than 500 examinations with each mobile gynaecological office. Financial resources of BGN 12,500 were allocated for each mobile unit, totalling BGN 50,000 for the four units. During the reporting period, the mobile gynecological offices were divided into four areas: Varna (the city of Varna, the village of Kamenar, the town of Ignatievo, the village of Staro Oryahovo, the village of Sindel, the village of Dubravino, the town of Provadia, the town of Devnya, the town of Suvorovo, the village of Chernevo, the town of Valchi Dol); Silistra (Tutrakan Municipality– the town of Tutrakan, the village of Tsar Samuel, the village of Nova Cherna, the village of Staro Selo, the village of Belitsa, the village of Preslavtsi, the village of Tarnovtsi, -

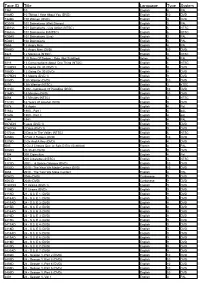

Tape ID Title Language Type System

Tape ID Title Language Type System 1361 10 English 4 PAL 1089D 10 Things I Hate About You (DVD) English 10 DVD 7326D 100 Women (DVD) English 9 DVD KD019 101 Dalmatians (Walt Disney) English 3 PAL 0361sn 101 Dalmatians - Live Action (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 0362sn 101 Dalmatians II (NTSC) English 6 NTSC KD040 101 Dalmations (Live) English 3 PAL KD041 102 Dalmatians English 3 PAL 0665 12 Angry Men English 4 PAL 0044D 12 Angry Men (DVD) English 10 DVD 6826 12 Monkeys (NTSC) English 3 NTSC i031 120 Days Of Sodom - Salo (Not Subtitled) Italian 4 PAL 6016 13 Conversations About One Thing (NTSC) English 1 NTSC 0189DN 13 Going On 30 (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 7080D 13 Going On 30 (DVD) English 9 DVD 0179DN 13 Moons (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 3050D 13th Warrior (DVD) English 10 DVD 6291 13th Warrior (NTSC) English 3 nTSC 5172D 1492 - Conquest Of Paradise (DVD) English 10 DVD 3165D 15 Minutes (DVD) English 10 DVD 6568 15 Minutes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 7122D 16 Years Of Alcohol (DVD) English 9 DVD 1078 18 Again English 4 Pal 5163a 1900 - Part I English 4 pAL 5163b 1900 - Part II English 4 pAL 1244 1941 English 4 PAL 0072DN 1Love (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0141DN 2 Days (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0172sn 2 Days In The Valley (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 3256D 2 Fast 2 Furious (DVD) English 10 DVD 5276D 2 Gs And A Key (DVD) English 4 DVD f085 2 Ou 3 Choses Que Je Sais D Elle (Subtitled) French 4 PAL X059D 20 30 40 (DVD) English 9 DVD 1304 200 Cigarettes English 4 Pal 6474 200 Cigarettes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 3172D 2001 - A Space Odyssey (DVD) English 10 DVD 3032D 2010 - The Year -

Lunatics I 08 **** **** **** **** **** ********* ********* the LUNATICS NEWLETTER ©

Lunatics I 08 **** **** **** **** **** ********* ********* THE LUNATICS NEWLETTER © THE LUNATICS NEWSLETTER, Year I, N° 8, 10/09/2003 SUMMARY. Available in this number: 1) THE DARK SIDE OF THE MOON Yugoslavia special 2LP 2) THE DARK SIDE OF THE MOON Yugoslavia 2LP special radio promo 3) THE DARK SIDE OF THE MOON U.S.A. RTI testpressing 4) The swiss Silva company ~·~·~·~·~·~·~·~·~·~·~·~·~·~·~·~·~·~·~·~·~·~·~·~·~·~·~ 1) THE DARK SIDE OF THE MOON Yugoslavia special 2LP. (by Stefano Tarquini) special rare pressing by The Quadraphonic SQ System, from Yugoslavia, contains 2 LPs with different labels. Company: EMI-HARVEST-JUGOTON Catalog number: LQEMI 73009 Frontcover: standard black cover with prism, title inside two round stickers (attached in the upper left and printed in the bottom right), blue Jugoton logo in the bottom left, and the "Quadraphonic SQ System" logo in the bottom right. Backcover: standard, with the catalog number "LQEMI-73009" in the upper right (blue letters), in the bottom right shows a mark. Spine: none text. Inside: standard, blue text, in the half left shows the Harvest logo, the text "EMI Records Ltd." "HAYES MIDDLESEX ENGLAND", the "QUADRAPHONIC SQ SYSTEM" logo, in the bottom right shows the Jugoton logo and the text "PODUZECE ZA IZRADU GRAMOFONSKIH PLOCA ZAGREB - DUBRAVA MADE IN YUGOSLAVIA". Inner: clear. Labels details. A) First record. the first LP shows a classic black label with blue prism, text is on silver letters, on the right shows the catalog number "LQEMI-73009" and below the additional number "(Q4SHVL 804)" -

1 En Petkovic

Scientific paper Creation and Analysis of the Yugoslav Rock Song Lyrics Corpus from 1967 to 20031 UDC 811.163.41’322 DOI 10.18485/infotheca.2019.19.1.1 Ljudmila Petkovi´c ABSTRACT: The paper analyses the pro- [email protected] cess of creation and processing of the Yu- University of Belgrade goslav rock song lyrics corpus from 1967 to Belgrade, Serbia 2003, from the theoretical and practical per- spective. The data have been obtained and XML-annotated using the Python program- ming language and the libraries lyricsmas- ter/yattag. The corpus has been preprocessed and basic statistical data have been gener- ated by the XSL transformation. The diacritic restoration has been carried out in the Slovo Majstor and LeXimir tools (the latter appli- cation has also been used for generating the frequency analysis). The extraction of socio- cultural topics has been performed using the Unitex software, whereas the prevailing top- ics have been visualised with the TreeCloud software. KEYWORDS: corpus linguistics, Yugoslav rock and roll, web scraping, natural language processing, text mining. PAPER SUBMITTED: 15 April 2019 PAPER ACCEPTED: 19 June 2019 1 This paper originates from the author’s Master’s thesis “Creation and Analysis of the Yugoslav Rock Song Lyrics Corpus from 1945 to 2003”, which was defended at the University of Belgrade on March 18, 2019. The thesis was conducted under the supervision of the Prof. Dr Ranka Stankovi´c,who contributed to the topic’s formulation, with the remark that the year of 1945 was replaced by the year of 1967 in this paper. -

Prädikate 1993-2002

Filmprädikate (1993 - 2002) 1993 BESONDERS WERTVOLL 1993-01-18 WIEDERSEHEN IN HOWARDS END 1993-02-10 GESTOHLENE KINDER 1993-02-15 EHEMÄNNER UND EHEFRAUEN 1993-02-15 EIN GANZ NORMALER HELD 1993-03-24 EHEMÄNNER UND EHEFRAUEN 1993-03-24 EIN GANZ NORMALER HELD 1993-05-13 FALLING DOWN - EIN GANZ NORMALER TAG 1993-06-02 DIE REISE - DAS ABENTEUER, JUNG ZU SEIN 1993-07-07 BENNY & JOON 1993-07-26 THE PIANO 1993-07-29 BENNY & JOON 1993-08-17 VIEL LÄRM UM NICHTS 1993-09-29 FIORILE 1993-10-29 ZEIT DER UNSCHULD 1993-11-03 DREI FARBEN BLAU 1993-11-16 DAS PIANO 1993-11-25 ZEIT DER UNSCHULD 1993-12-21 SHORT CUTS WERTVOLL 1993-01-11 GLENGARRY GLEN ROSS 1993-01-11 STALINGRAD 1993-01-19 DER REPORTER 1993-01-27 VERHÄNGNIS 1993-02-05 SOMMERSBY 1993-02-08 DER DUFT DER FRAUEN 1993-02-08 WATERLAND 1993-02-11 GLENGARRY GLEN ROSS 1993-03-08 ORLANDO 1993-03-10 VERZAUBERTER APRIL 1993-03-11 LORENZOS ÖL 1993-03-11 DER DUFT DER FRAUEN 1993-03-26 SOMMERSBY 1993-04-21 AUS DER MITTE ENTSPINGT EIN FLUSS 1993-04-28 LORENZOS ÖL 1993-05-13 DER REPORTER 1993-07-05 BITTERSÜSSE SCHOKOLADE 1993-07-14 DAVE - BESSER ALS DAS ORIGINAL ERLAUBT 1993-07-26 BORN YESTERDAY - BLONDINEN KÜSST MAN NICHT 1993-07-26 DIE KRISE 1993-08-17 IN WEITER FERNE, SO NAH! 1993-08-17 SCHLAFLOS IN SEATTLE 1993-09-22 INDIEN 1993-09-29 DAS GEISTERHAUS 1993-09-30 KINDERSPIELE PDF created with pdfFactory trial version www.pdffactory.com 1993-10-05 SCHLAFLOS IN SEATTLE 1993-10-13 JUSTIZ 1993-11-03 DER MANN OHNE GESICHT 1993-11-18 PASSION FISH SEHENSWERT 1993-01-11 BRAM STOKER'S DRACULA 1993-01-14 SNEAKERS -

Les Américains Et Les Autres André Roy

Document généré le 2 oct. 2021 04:49 24 images Les américains et les autres André Roy Numéro 66, avril–mai 1993 URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/22745ac Aller au sommaire du numéro Éditeur(s) 24/30 I/S ISSN 0707-9389 (imprimé) 1923-5097 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Roy, A. (1993). Les américains et les autres. 24 images, (66), 50–51. Tous droits réservés © 24 images inc., 1993 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. https://www.erudit.org/fr/ 43e festival de Berlin sélection officielle, qui a croulé sous l'académisme, avec Le té légraphiste, du Norvégien Erik Gustavson et Chagrin damour, du Suédois Nils Malmros, pour donner deux exemples extrêmes. LES AMÉRICAINS ET LES AUTRES On a surtout eu comme impres sion que les cinéastes avaient par André Roy envie de présenter un travail propre, convenu, sans aucune audace. Les deux films qui ont eu conjointement l'Ours d'or le n n'a cessé, au fil des ans, Vito, Love Field, de Jonathan quentée et les cinéastes ont pro prouvent amplement. O d'accuser le Festival de Kaplan, Malcolm X, de Spike testé contre cette ghettoïsation La noce, du Taïwanais Ang Berlin, surtout avec sa compé Lee, Toys, de Barry Levinson et de leur cinéma. -

American Foreign Policy, the Recording Industry, and Punk Rock in the Cold War

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University History Dissertations Department of History Spring 5-10-2017 Music for the International Masses: American Foreign Policy, The Recording Industry, and Punk Rock in the Cold War Mindy Clegg Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_diss Recommended Citation Clegg, Mindy, "Music for the International Masses: American Foreign Policy, The Recording Industry, and Punk Rock in the Cold War." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2017. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_diss/58 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MUSIC FOR THE INTERNATIONAL MASSES: AMERICAN FOREIGN POLICY, THE RECORDING INDUSTRY, AND PUNK ROCK IN THE COLD WAR by MINDY CLEGG Under the Direction of ALEX SAYF CUMMINGS, PhD ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the connections between US foreign policy initiatives, the global expansion of the American recording industry, and the rise of punk in the 1970s and 1980s. The material support of the US government contributed to the globalization of the recording industry and functioned as a facet American-style consumerism. As American culture spread, so did questions about the Cold War and consumerism. As young people began to question the Cold War order they still consumed American mass culture as a way of rebelling against the establishment. But corporations complicit in the Cold War produced this mass culture. Punks embraced cultural rebellion like hippies. -

Repertoar La LUNA Band-A Naziv Izvodjac STRANE PESME Chain of Fools Aretha Franklin the Girl from Ipanema Astrud Gilberto Stand by Me Ben E

Repertoar La LUNA band-a naziv Izvodjac STRANE PESME Chain of Fools Aretha Franklin The Girl from Ipanema Astrud Gilberto Stand by Me Ben E. King Summertime Billie Holiday,Ella Fitzgerald,Sarah Vaughan White Wedding Billy Idol Knockin' on heaven's Door Bob Dylan No Woman No Cry Bob Marley Let's Stick Together Bryan Ferry Chan Chan Buena Vista Social Club El Cuarto de Tula Buena Vista Social Club Veinte Anos Buena Vista Social Club Hasta siempre Comandante Che Guevara Carlos Puebla Dove l'amore Cher I Still Haven't Found What I'm Looking For Coco Freeman feat. U2 Just A Gigolo David Lee Roth Money For Nothing Dire Straits Long Train Running Doobie Brothers Gimme Hope Jo'Anna Eddy Grant Non, je ne regrette rien Edith Piaf Blue Spanish Eyes Elvis Presley Blue Suede Shoes Elvis Presley Suspicious Minds Elvis Presley Viva Las Vegas Elvis Presley Love Me Tender Elvis Presley Besame mucho Emilio Tuero Please release Me Engelbert Humperdinck Change The World Eric Clapton Layla Eric Clapton Tears In Heaven Eric Clapton Wonderful Tonight Eric Clapton Malaika Fadhili Williams Easy Faith no More All of Me Frank Sinatra New York, New York Frank Sinatra Can't Take My Eyes Off You Frankie Valli Careless Whisper George Michael Nathalie Gilbert Becaud Baila me Gipsy Kings Bamboleo Gipsy Kings Repertoar La LUNA band-a naziv Izvodjac Trista Pena Gipsy Kings I will survive Gloria Gaynor Libertango Grace Jones I Feel Good James Brown Por Que Te Vas Javier Alvarez Autumn Leaves/Les feuilles mortes Jo Elizabeth Stafford;Yves Montand Unchain my Heart Joe Cocker