A Great Architect

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phoenix Area Homes Include the Circular David Wright House (1952), 5212 East Exeter Blvd., Designed for His Son in North Phoenix (1950), and the H.C

CITY REPORT (Iraq) Opera House (never built), serves as a distinguished gateway to the Tempe campus of Arizona State University. Its president at the time, Grady Gammage, was a good friend of the architect. Wright’s First Christian Church (designed in 1948/built posthumously by the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation in 1973), 6750 N. Seventh Ave., incorporates desert masonry, as in Taliesin West, and features distinctive spires. Wright’s ten distinguished Phoenix area homes include the circular David Wright House (1952), 5212 East Exeter Blvd., designed for his son in north Phoenix (1950), and the H.C. Price House (1954), 7211 N. Tatum Blvd., with its graceful combination of concrete block, steel and copper in a foothills setting. Wright’s approach continued through his pupils, such as Albert Chase McArthur, who is generally credited with the design of the spectacular Arizona Biltmore Hotel (1928), 24th St. and Missouri Ave. Wright’s influence on the building is clear in both massing and details, including the distinctive concrete Biltmore Blocks, cast onsite to an Emry Kopta design. The hotel was Foundation. Photo by Lara Corcoran, courtesy Frank Lloyd Wright restored after a fire in 1973, and additions were built in 1975 and 1979. Blaine Drake was another student who, with Alden Dow, designed the original Phoenix Art Museum, Theater and Library Complex and East Wing (1959, 1965), 1625 N. Central Ave. (Tod Williams and Billie Tsien Architects, New York, designed additions in 1996 and 2006.) Drake also designed the first addition to the Heard Museum (1929), 22 E. Monte Vista Rd., a PHOENIX: UP FROM THE DESERT Spanish Colonial Revival by H.H. -

Reciprocal Sites Membership Program

2015–2016 Frank Lloyd Wright National Reciprocal Sites Membership Program The Frank Lloyd Wright National Reciprocal Sites Program includes 30 historic sites across the United States. FLWR on your membership card indicates that you enjoy the National Reciprocal sites benefit. Benefits vary from site to site. Please check websites listed in this brochure for detailed information on each site. ALABAMA ARIZONA CALIFORNIA FLORIDA 1 Rosenbaum House 2 Taliesin West 3 Hollyhock House 4 Florida Southern College 601 RIVERVIEW DRIVE 12621 N. FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT BLVD BARNSDALL PARK 750 FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT WAY FLORENCE, AL 35630 SCOTTSDALE, AZ 85261-4430 4800 HOLLYWOOD BLVD LAKELAND, FL 33801 256.718.5050 480.860.2700 LOS ANGELES, CA 90027 863.680.4597 ROSENBAUMHOUSE.COM FRANKLLOYDWRIGHT.ORG 323.644.6269 FLSOUTHERN.EDU/FLW WRIGHTINALABAMA.COM FOR UP-TO-DATE INFORMATION BARNSDALL.ORG FOR UP-TO-DATE INFORMATION FOR UP-TO-DATE INFORMATION TOUR HOURS: 9AM–4PM FOR UP-TO-DATE INFORMATION TOUR HOURS: TOUR HOURS: BOOKSHOP HOURS: 8:30AM–6PM TOUR HOURS: THURS–SUN, 11AM–4PM OPEN ALL YEAR, EXCEPT OPEN ALL YEAR, EXCEPT TOUR TICKETS AVAILABLE AT THE THANKSGIVING, CHRISTMAS AND NEW Experience firsthand Frank Lloyd MAJOR HOLIDAYS. HOLLYHOCK HOUSE VISITOR’S CENTER YEAR’S DAY. 10AM–4PM Wright’s brilliant ability to integrate TUES–SAT, 10AM–4PM IN BARNSDALL PARK. VISITOR CENTER & GIFT SHOP HOURS: SUN, 1PM–4PM indoor and outdoor spaces at Taliesin Hollyhock House is Wright’s first 9:30AM–4:30PM West—Wright’s winter home, school The Rosenbaum House is the only Los Angeles project. Built between and studio from 1937-1959, located Discover the largest collection of Frank Lloyd Wright-designed 1919 and 1923, it represents his on 600 acres of dramatic desert. -

The 20Th-Century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright National Locator Unity Temple, Oak Park, Illinois

The 20th-Century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright National Locator Unity Temple, Oak Park, Illinois 87.800° W 87.795° W 87.790° W Erie St N Grove Ave Grove N 41.8902° N, 87.7947° W Ontario St 41.8901° N, 87.7992° W E E 41.890° N 41.890° N Austin Garden Park Scoville Park N Euclid Ave Euclid N N Linden Ave Linden N Forest Ave Forest N Oak Park Ave Park Oak N N Kenilworth Ave Kenilworth N Lake St Unity Temple ! 41.888° N 41.888° N E 41.8878° N, 87.7995° W E North Blvd 41.8874° N, 87.7946° W South Blvd 41.886° N 41.886° N Home Ave Home S Grove Ave Grove S S Euclid Ave Euclid S S Clinton Ave Clinton S S Wesley Ave Wesley S S Oak Park Ave Park Oak S S Kenilworth Ave Kenilworth S 87.800° W 87.795° W Pleasant St 87.790° W Nominated National Historic Projection: Lambert Conformal Conic 1:4,500 Green Space/Park Datum: North American Datum 1983 Property Landmark Production Date: October 2015 0 100 Meters ! Gould Center, Department of Geography ¹ Buffer Zone Center Point Buildings The Pennsylvania State University Frederick C. Robie House, Chicago, Illinois Frederick C. Robie House, Chicago, Illinois 87.600° W 87.598° W 87.596° W Ave Kimbark S 87.594° W 87.592° W S Woodlawn Ave Woodlawn S E 57th St 41.791° N 41.791° N S Kimbark Ave Kimbark S 41.7904° N, 87.5972° W E41.7904 N, 87.5957° W S Ellis Ave Ellis S E S Kenwood Avenue Kenwood S Frederick C. -

Jenkin Lloyd Jones Jr

Jenkin Lloyd Jones Jr. Through the headlines of the Tulsa Tribune the Jones family has been a part of local and national history. Chapter 01 – 1:15 Introduction Announcer: The grandfather of Jenkin Lloyd Jones Jr., Richard Lloyd Jones, bought the Tulsa Democrat from Sand Springs founder Charles Page, and turned it into the Tribune. The Tulsa Tribune was an afternoon newspaper and consistently republican; it never endorsed a democrat for U.S. president and did not endorse a democrat for governor until 1958. Jenkin Lloyd Jones Sr. was editor of the Tribune from 1941 to 1988, and publisher until 1991. Jenkin Jones brother Richard Lloyd Jones was the Tribune’s president. Jones Airport in Tulsa is named for Richard Lloyd Jones Jr. Other Jones family members served in various capacities on the paper, including Jenkin’s son, Jenkin Lloyd Jones Jr., who was the last publisher and editor of the paper which closed September 30, 1992. Like other large city evening newspapers, its readership had declined, causing financial losses. Jenk Jones spent thirty-two years at the Tulsa Tribune in jobs ranging from reporter to editor and publisher. He is a member of the Oklahoma Journalism Hall of Fame and the Universtiy of Tulsa Hall of Fame. And now Jenk Jones tells the story of his family and the Tulsa Tribune on Voices of Oklahoma, preserving our state’s history, one voice at a time. Chapter 02 – 12:05 Jones Family John Erling: My name is John Erling and today’s date is February 25, 2011. Jenk, state your full name, please, your date of birth, and your present age. -

One Man's Quest to Photograph Every Frank Lloyd Wright Structure Ever Built

One Man's Quest to Photograph Every Frank Lloyd Wright Structure Ever Built architecturaldigest.com /story/frank-lloyd-wright-photographer-andrew-pielage Chris Malloy There are 532 Frank Lloyd Wright structures standing in the world. Phoenix-based photographer Andrew Pielage is on a mission to shoot every one of them. The 39-year-old is the unofficial photographer of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. So far, he has shot about 50 Wright structures. His quest to shoot Wright’s oeuvre began in 2011, when he first toured Taliesin West, Wright’s former winter home and studio outside Phoenix. Photography wasn’t allowed on that tour. But later a friend connected Pielage with the folks at Taliesin West, and for them Pielage shot the sprawling stone-and-wood compound. The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation loved his work, and he became its unofficial photographer. Since then, Pielage has shot Wright’s Hollyhock House (Los Angeles), Unity Temple (Illinois), Taliesin (Wisconsin), and Fallingwater (Pennsylvania), where he did a three-week residence. “When you have that much time to shoot a property, you get to know the ins and outs,” he says. What impressed him was how, against the grain of the bright shots one typically sees of the house, Fallingwater, on cloudy days, “turns gray so that the building’s personality changes with the environment.” The spirit of Wright’s organic style, of structures inspired by and seamlessly integrated into the natural world, whether desert or city or forest, has challenged Pielage. How can one properly capture this architectural titan’s work? Pielage has developed tricks. -

Stained Glass Window Designs of Frank Lloyd Wright Pdf, Epub, Ebook

STAINED GLASS WINDOW DESIGNS OF FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Dennis Casey | 32 pages | 21 Mar 1997 | Dover Publications Inc. | 9780486295169 | English | New York, United States Stained Glass Window Designs of Frank Lloyd Wright PDF Book They are similar to the windows of the Dana house, incorporating similar motifs and the same materials. Taliesin is like a brow because it sets on the side of a hill. You might like to try orange muntins in a plain white kitchen, for instance. In , he redrew the plans, changing the stucco exterior to concrete. The house sat on an acre estate and also included a studio and architecture school. About one hundred of Frank Lloyd Wright's buildings have been destroyed for various reasons. Without the casement sash, Wright probably would not have developed the complex and intriguing ornamental patterns found in his windows. Wright gave no specific titles to them. The Larkin Building was modern for its time, with conveniences like air conditioning. Rogers for his daughter and her husband, Frank Wright Thomas. Although Victorian in inspiration, it is a stepping stone to the Prairie window, to which Wright was able to leap directly in in his Studio office and reception room, which he added to his home in that year. Taliesin West is a school for architecture, but it also served as Wright's winter home until his death in The Storer House is another example of Wright using ancient Mayan influences. Striking Minimalism Classic black and white might not seem all that adventurous, but it brings a timeless sense of style to any home window design. -

Full List of Book Discussion Kits – September 2016

Full List of Book Discussion Kits – September 2016 1776 by David McCullough -(Large Print) Esteemed historian David McCullough details the 12 months of 1776 and shows how outnumbered and supposedly inferior men managed to fight off the world's greatest army. Abraham: A Journey to the Heart of Three Faiths by Bruce Feiler - In this timely and uplifting journey, the bestselling author of Walking the Bible searches for the man at the heart of the world's three monotheistic religions -- and today's deadliest conflicts. Abundance: a novel of Marie Antoinette by Sena Jeter Naslund - Marie Antoinette lived a brief--but astounding--life. She rebelled against the formality and rigid protocol of the court; an outsider who became the target of a revolution that ultimately decided her fate. After This by Alice McDermott - This novel of a middle-class American family, in the middle decades of the twentieth century, captures the social, political, and spiritual upheavals of their changing world. Ahab's Wife, or the Star-Gazer by Sena Jeter Naslund - Inspired by a brief passage in Melville's Moby-Dick, this tale of 19th century America explores the strong-willed woman who loved Captain Ahab. Aindreas the Messenger: Louisville, Ky, 1855 by Gerald McDaniel - Aindreas is a young Irish-Catholic boy living in gaudy, grubby Louisville in 1855, a city where being Irish, Catholic, German or black usually means trouble. The Alchemist by Paulo Coelho - A fable about undauntingly following one's dreams, listening to one's heart, and reading life's omens features dialogue between a boy and an unnamed being. -

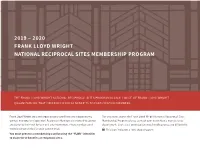

2019 – 2020 Frank Lloyd Wright National Reciprocal Sites Membership Program

2019 – 2020 FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT NATIONAL RECIPROCAL SITES MEMBERSHIP PROGRAM THE FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT NATIONAL RECIPROCAL SITES PROGRAM IS AN ALLIANCE OF FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT ORGANIZATIONS THAT OFFER RECIPROCAL BENEFITS TO PARTICIPATING MEMBERS. Frank Lloyd Wright sites and organizations listed here are independently For questions about the Frank Lloyd Wright National Reciprocal Sites owned, managed and operated. Reciprocal Members are advised to contact Membership Program please contact your institution’s membership sites prior to their visit for tour and site information. Phone numbers and department. Each site / organization may handle processing differently. websites are provided for your convenience. This icon indicates a 10% shop discount. You must present a membership card bearing the “FLWR” identifier to claim these benefits at reciprocal sites. 2019 – 2020 MEMBER BENEFITS ARIZONA THE ROOKERY 209 S LaSalle St Chicago, IL 60604 TALIESIN WEST lwright.org 312.994.4000 12345 N Taliesin Dr Scottsdale, AZ 85259 Beneits: Two complimentary tours franklloydwright.org 888.516.0811 Beneits: Two complimentary admissions to the 90-minute Insights tours. INDIANA Reservations recommended. THE JOHN AND CATHERINE CHRISTIAN HOUSE-SAMARA CALIFORNIA 1301 Woodland Ave West Lafayette, IN 47906 samara-house.org 765.409.5522 HOLLYHOCK HOUSE Beneits: One complimentary tour 4800 Hollywood Blvd Los Angeles, CA 90026 barnsdall.org IOWA Beneits: Two complimentary self-guided tours MARIN COUNTY CIVIC CENTER THE HISTORIC PARK INN HOTEL (CITY NATIONAL BANK AND 3501 -

Authors on Architecture 1

SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL January/February HISTORIANS/ SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA CHAPTER NEWS 2019 Authors on Architecture 1 President’s Letter 2 2018 Year in Review 3 SAH/SCC Publications for Sale 5 IN THIS ISSUE DLTA Revival Tour 6 Authors on Architecture: Smith on Wright SAH/SCC Lecture & Book Signing, Santa Monica Sunday, March 17, 2019, 2-4PM Join SAH/SCC as we explore a fascinating aspect of the legacy of Frank Lloyd Wright. Author Kathryn Smith will deliver a lecture on her latest book, Wright on Exhibit (Princeton University Press, 2017), at Santa Monica Public Library (Moore Ruble Yudell, 2006). More than 100 exhibitions of Frank Lloyd Wright’s work were mounted between 1894 and his death in 1959. Wright organized the majority of these exhibitions himself and viewed them as crucial to his self-presentation, as he did his extensive writings. He used them to promote his designs, appeal to new viewers, and persuade his detractors. Wright on Exhibit presents the first history of this neglected aspect of the architect’s influential career. Drawing extensively from Wright’s unpublished correspondence, Smith challenges the preconceived notion of Wright as a self-promoter who displayed his work in search of money, clients, and fame. She shows how he was an artist-architect projecting an avant-garde program, an innovator who expanded the palette of installation design “Sixty Years of Living Architecture” at the Guggenheim Museum in 1953. as technology evolved, and a social activist driven to revolutionize Photo: Pedro E. Guerrero society through design. Wright on Exhibit features color renderings, photos, and plans, as well as a checklist of exhibitions and an illustrated catalog of extant and lost models made under Wright’s supervision. -

Loving Frank

Loving Frank by John Burnham Schwartz Based on the novel by Nancy Horan Escape Artists Draft of: 10/13/09 Lionsgate Entertainment OVER A BLACK SCREEN: THE SOUND OF HAMMERING. EXT. NEW YORK, GUGGENHEIM MUSEUM - DAY (1958) A long, still WIDE SHOT of the museum’s facade: a temple of sculptural perfection. A checker CAB rolls down Fifth Avenue. Then a 1957 CADILLAC, followed by a late 1950’s New York City BUS. TWO MEN in fedoras and suits stroll through frame, stopping briefly to stare up at the building. We PRESS FORWARD into the space where the men just were, closer to the building, CLOSER, passing through the walls... INT. GUGGENHEIM, ATRIUM - CONTINUOUS Inside. WORKMEN and islands of SCAFFOLDING punctuate the vast open atrium. Ethereal light pours down from the huge skylight above. The building is still unfinished. SUPER: 1958. The HAMMERING continues, louder now, mixed with other sounds of CONSTRUCTION. One by one, the workmen stop hammering, doff their caps and stand at respectful attention. FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT, 91 and still arrogantly handsome, dressed in a black broad-brimmed hat and dark suit, stands in the center of the atrium, surveying the space and light. Pleased, but not satisfied. Seeing something that we are not seeing. He nods perfunctorily at the workmen and begins to walk slowly up the long, spiralling RAMP. The workmen stare after him -- the greatest architect of their time -- then return to work. INT. GUGGENHEIM, RAMP - CONTINUOUS Alone, slowly, Frank ascends the ramp. Looking critically at things -- the quality of plasterwork, cavities in the walls and ceilings where lights will be -- but also, the higher he goes, the more he seems to be entering another state of mind, a place of his own. -

Frank Lloyd Wright Chicago to New York

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT CHICAGO TO NEW YORK 5-night optional extension to Los Angeles & Taliesin West OCTOBER 22 – NOVEMBER 5, 2017 TOUR LEADER: STUART BARRIE FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT Overview CHICAGO TO NEW YORK Follow the journey of Frank Lloyd Wright from his original Prairie House Tour dates: October 22 – November 5, 2017 designs to the magnificent Fallingwater and Guggenheim Museum while at the same time enjoying the wealth of art, architecture and history in Tour leader: Stuart Barrie some of America’s most famous cities. We begin with four nights in Chicago, the ‘second city’ of the United Tour Price: $11,790 per person, twin share States, where Wright developed his Prairie style of architecture. It brims with fine buildings, art galleries and exuberant public sculpture. We then Single Supplement: $2,710 for sole use of travel north to Wisconsin to see some of Wright’s most famous works as double room well as Taliesin, his beloved estate. Our next stop is Buffalo, near Niagara Falls, to visit the Darwin Martin complex of houses. Travelling to Booking deposit: $500 per person Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, we take a day trip to America’s most famous house, Fallingwater. The tour concludes with four days in New York, home Recommended airline: Qantas or United to an extraordinary range of cultural sites and experiences. We take architectural walking tours, visit major galleries and attend a Broadway Maximum places: 20 show. The tour ends with Wright’s Guggenheim Museum on Fifth Avenue. Itinerary: Chicago (4 nights), Madison (2 Accommodation is in comfortable four and five star hotels throughout, with nights), Buffalo (2 nights), Pittsburgh (2 nights), breakfast daily, and several special meals at carefully chosen restaurants New York (4 nights) are included. -

Eight Frank Lloyd Wright Sites Inscribed on UNESCO World Heritage List

Eight Frank Lloyd Wright Sites Inscribed on UNESCO World Heritage List franklloydwright.org/eight-frank-lloyd-wright-sites-inscribed-on-unesco-world-heritage-list July 6, 2019 Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation | Jul 7, 2019 The inscription of a collection of eight Frank Lloyd Wright-designed buildings marks the first modern architecture designation on the UNESCO World Heritage List in the United States. After more than 15 years of extensive, collaborative efforts, eight of Frank Lloyd Wright’s major works have officially been inscribed to the UNESCO World Heritage List by the World Heritage Committee. The Wright sites that have been inscribed include Unity Temple, the Frederick C. Robie House, Taliesin, Hollyhock House, Fallingwater, the Herbert and Katherine Jacobs House, Taliesin West, and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. The collection of buildings, formally known in the nomination as The 20th-Century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright, span 50 years of Wright’s influential career, and mark the first modern architecture designation in the United States on the World Heritage List. Of the 1,092* World Heritage sites around the world, the group of Wright sites will now join an existing list of 23* sites in the United States. Be a part of history—join us in celebrating this special inscription with a gift to support the preservation of our two UNESCO World Heritage sites, Taliesin and Taliesin West. 1/4 The nomination was a coordinated effort led by The Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy, an international organization dedicated to the preservation of all of Wright’s remaining built works, with each of the nominated sites as well as independent scholars, generous subsidies and donations, countless hours donated by staff and volunteers, and the guidance of the National Park Service.