News Census Helps Palestinians in Jerusalem Numbers Game

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rapport Des Chefs De Mission Diplomatiques De L'union

Rapport des Chefs de Mission Diplomatiques de l’Union Européenne sur Jérusalem 2017 Note de synthèse Les Chefs de Mission à Jérusalem et à Ramallah soumettent par le présent document au Comité Politique et de Sécurité le rapport sur Jérusalem pour 2017 (annexe 1) et une série de recommandations pour discussion pour renforcer la politique de l’Union Européenne sur Jérusalem Est (Annexe 2). L’annexe 3 contient des faits supplémentaires et des chiffres sur Jérusalem. Les développements intervenus en 2017 ont encore accéléré les difficultés de la solution « des deux Etats » en l’absence de processus de paix significatif. Les tendances précédentes, observées et décrites par les Chefs de Mission Diplomatiques depuis plusieurs années, se sont empirées. La mise à l’écart des Palestiniens de la vie ordinaire, politique, économique et sociale de la ville sont largement inchangées. Le développement d’un nombre record de plans de colonisation s’est poursuivi, y compris dans des zones identifiées par l’Union Européenne et ses Etats membres comme clés pour une solution « des deux Etats ». En même temps, les démolitions de logements palestiniens se sont poursuivies, et plusieurs familles palestiniennes ont été expulsées de leurs logements au bénéfice de colons. Les tensions autour du Dôme du Rocher / Mont du Temple continuent. Au cours de cette année, plusieurs projets de lois à la Knesset ont poursuivi leur avancée législative, qui, s’ils étaient adoptés, apporteraient des changements unilatéraux au statut et aux frontières de Jérusalem, en violation du droit international. En fin d’année, les Etats Unis ont annoncé leur reconnaissance de Jérusalem comme capitale d’Israël. -

The Next Jerusalem

The Next Introduction1 Jerusalem: Since the beginning of the Israeli-Palestinian Potential Futures conflict, the city of Jerusalem has been the subject of a number of transformations that of the Urban Fabric have radically changed its urban structure. Francesco Chiodelli Both the Israelis and the Palestinians have implemented different spatial measures in pursuit of their disparate political aims. However, it is the Israeli authorities who have played the key role in the process of the “political transformation” of the Holy City’s urban fabric, with the occupied territories of East Jerusalem, in particular, being the object of Israeli spatial action. Their aim has been the prevention of any possible attempt to re-divide the city.2 In fact, the military conquest in 1967 was not by itself sufficient to assure Israel that it had full and permanent The wall at Abu Dis. Source: Photo by Federica control of the “unified” city – actually, the Cozzio (2012) international community never recognized [ 50 ] The Next Jerusalem: Potential Futures of the Urban Fabric the 1967 Israeli annexation of the Palestinian territories, and the Palestinians never ceased claiming East Jerusalem as the capital of a future Palestinian state. So, since June 1967, after the overtly military phase of the conflict, Israeli authorities have implemented an “urban consolidation phase,” with the aim of making the military conquests irreversible precisely by modifying the urban space. Over the years, while there have been no substantial advances in terms of diplomatic agreements between the Israelis and the Palestinians about the status of Jerusalem, the spatial configuration of the city has changed constantly and quite unilaterally. -

![Arij Daily Report] June 2019](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2464/arij-daily-report-june-2019-52464.webp)

Arij Daily Report] June 2019

[ARIJ DAILY REPORT] JUNE 2019 Israeli Violations' Activities in the oPt 27 June 2019 The daily report highlights the violations behind Israeli home demolitions and demolition threats The Violations are based on in the occupied Palestinian territory, the reports provided by field workers confiscation and razing of lands, the uprooting and\or news sources. and destruction of fruit trees, the expansion of The text is not quoted directly settlements and erection of outposts, the brutality from the sources but is edited for of the Israeli Occupation Army, the Israeli settlers clarity. violence against Palestinian civilians and properties, the erection of checkpoints, the The daily report does not construction of the Israeli segregation wall and necessarily reflect ARIJ’s opinion. the issuance of military orders for the various Israeli purposes. This DAILY REPORT is prepared as part of the project entitled Advocating for a Sustainable and Viable Resolution of Israeli-Palestinian Conflict which is financially supported by the EU. However, the content of this presentation is the sole responsibility of ARIJ & LRC and does not necessarily reflect those of the donors. 1 [ARIJ DAILY REPORT] JUNE 2019 Brutality of the Israeli Occupation Army • The Israeli Occupation Army (IOA) invaded Beit Ummar town, north of the southern West Bank city of Hebron, and searched many homes. (IMEMC 27 June 2019) Israeli Arrests • Several armored Israeli military jeeps invaded Jenin city, Jenin refugee camp and Sielet al-Harithiyya town, in northern West Bank, searched and ransacked many homes, and detained four Palestinians, in addition to wounding many others during ensuing protests. The IOA detained Jihad Tawalba, Ahmad Mohammad Shaqfa and a former political prisoner, identified as Abdullah al-Hosary, from their homes in Jenin refugee camp. -

Marah Al-Bakri (Website of 48Arab)

November 2, 2015 Initial Findings of the Profile of Palestinian Terrorists Who Carried Out Attacks in Israel in the Current Wave of Terrorism (Updated to October 25, 2015) The contagious effect of stabbing attacks: a notice posted to the Palestinian social networks, some of them affiliated with Hamas, reading "If you don't stand up for Jerusalem, who will?" It features recent postings written by terrorist operatives Muhannad Shafiq and Fadi Aloun, who were killed carrying out stabbing attacks in Jerusalem and became role models for terrorists who followed in their footsteps. Overview 1. The wave of Palestinian violence and terrorism currently plaguing Israel began during the most recent Jewish High Holidays. In retrospect, the ITIC has concluded it began with the stones thrown at the vehicle of Alexander Levlowitz near the Armon Hanatziv neighborhood of Jerusalem on September 14, 2015. Initially the wave of violence and terrorism focused on the Temple Mount and east Jerusalem and later spread throughout Jerusalem and to other sites inside Israel and various hotspots in Judea and Samaria (especially the region around Hebron). So far 12 1 Israelis and more than 70 Palestinians have been killed. 1 According to a spokesman of the Palestinian ministry of health so far 61 Palestinians have been killed (Voice of Palestine Radio, October 26, 2015). According to the written Palestinian media 71 Palestinians 179-15 2 2. The current wave of violence and terrorism is part of the overall "popular resistance" strategy adopted by the Palestinian Authority (PA) and Fatah at the Sixth Fatah Conference in August 2009.2 It is manifested by rising and falling levels of popular terrorism. -

Sur Bahir & Umm Tuba Town Profile

Sur Bahir & Umm Tuba Town Profile Prepared by The Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem Funded by Spanish Cooperation 2012 Palestinian Localities Study Jerusalem Governorate Acknowledgments ARIJ hereby expresses its deep gratitude to the Spanish agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID) for their funding of this project. ARIJ is grateful to the Palestinian officials in the ministries, municipalities, joint services councils, village committees and councils, and the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) for their assistance and cooperation with the project team members during the data collection process. ARIJ also thanks all the staff who worked throughout the past couple of years towards the accomplishment of this work. 1 Palestinian Localities Study Jerusalem Governorate Background This report is part of a series of booklets, which contain compiled information about each city, village, and town in the Jerusalem Governorate. These booklets came as a result of a comprehensive study of all villages in Jerusalem Governorate, which aims at depicting the overall living conditions in the governorate and presenting developmental plans to assist in developing the livelihood of the population in the area. It was accomplished through the "Village Profiles and Needs Assessment;" the project funded by the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID). The "Village Profiles and Needs Assessment" was designed to study, investigate, analyze and document the socio-economic conditions and the needed programs and activities to mitigate the impact of the current unsecure political, economic and social conditions in the Jerusalem Governorate. The project's objectives are to survey, analyze, and document the available natural, human, socioeconomic and environmental resources, and the existing limitations and needs assessment for the development of the rural and marginalized areas in the Jerusalem Governorate. -

This Road Leads to Area “A” Under the Palestinian Authority, Beware of Entering: Palestinian Ghetto Policies in the West Bank

This Road Leads to Area “A” Under the Palestinian Authority, Beware of Entering: Palestinian Ghetto Policies in the West Bank Razi Nabulsi* “This road leads to Area “A” under the Palestinian Authority. The Entrance for Israeli Citizens is Forbidden, Dangerous to Your Lives, And Is Against The Israeli Law.” Anyone entering Ramallah through any of the Israeli military checkpoints that surround it, and surround its environs too, may note the abovementioned sentence written in white on a blatantly red sign, clearly written in three languages: Arabic, Hebrew, and English. The sign practically expires at Attara checkpoint, right after Bir Zeit city; you notice it as you leave but it only speaks to those entering the West Bank through the checkpoint. On the way from “Qalandia” checkpoint and until “Attara” checkpoint, the traveller goes through Qalandia Camp first; Kafr ‘Aqab second; Al-Amari Camp third; Ramallah and Al-Bireh fourth; Sarda fifth; and Birzeit sixth, all the way ending with “Attara” checkpoint, where the red sign is located. Practically, these are not Area “A” borders, but also not even the borders of the Ramallah and Al-Bireh Governorate, neither are they the West Bank borders. This area designated by the abovementioned sign does not fall under any of the agreed-upon definitions, neither legally nor politically, in Palestine. This area is an outsider to legal definitions; it is an outsider that contains everything. It contains areas, such as Kafr ‘Aqab and Qalandia Camp that belong to the Jerusalem municipality, which complies -

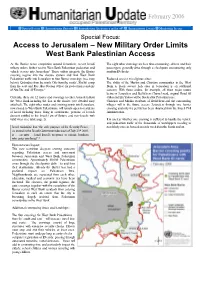

Access to Jerusalem – New Military Order Limits West Bank Palestinian Access

February 2006 Special Focus Humanitarian Reports Humanitarian Assistance in the oPt Humanitarian Events Monitoring Issues Special Focus: Access to Jerusalem – New Military Order Limits West Bank Palestinian Access As the Barrier nears completion around Jerusalem, recent Israeli The eight other crossings are less time-consuming - drivers and their military orders further restrict West Bank Palestinian pedestrian and passengers generally drive through a checkpoint encountering only vehicle access into Jerusalem.1 These orders integrate the Barrier random ID checks. crossing regime into the closure system and limit West Bank Palestinian traffic into Jerusalem to four Barrier crossings (see map Reduced access to religious sites: below): Qalandiya from the north, Gilo from the south2, Shu’fat camp The ability of the Muslim and Christian communities in the West from the east and Ras Abu Sbeitan (Olive) for pedestrian residents Bank to freely access holy sites in Jerusalem is an additional of Abu Dis, and Al ‘Eizariya.3 concern. With these orders, for example, all three major routes between Jerusalem and Bethlehem (Tunnel road, original Road 60 Currently, there are 12 routes and crossings to enter Jerusalem from (Gilo) and Ein Yalow) will be blocked for Palestinian use. the West Bank including the four in the Barrier (see detailed map Christian and Muslim residents of Bethlehem and the surrounding attached). The eight other routes and crossing points into Jerusalem, villages will in the future access Jerusalem through one barrier now closed to West Bank Palestinians, will remain open to residents crossing and only if a permit has been obtained from the Israeli Civil of Israel including those living in settlements, persons of Jewish Administration. -

Jerusalem Chronology 2015 January Jan. 1: the Israeli Supreme Court

Jerusalem Chronology 2015 January Jan. 1: The Israeli Supreme Court rejects an appeal to prevent the demolition of the homes of four Palestinians from East Jerusalem who attacked Israelis in West Jerusalem in recent months. - Marabouts at Al-Aqsa Mosque confront a group of settlers touring Al-Aqsa compound. Jan. 3: Palestinian MK Ahmad Tibi joins hundreds of Palestinians marching toward the Al-Aqsa Mosque in the Old City of Jerusalem to mark the Prophet Muhammad's birthday. Jan. 5: Settlers tour Al-Aqsa Mosque compound while Israeli forces confiscate the IDs of Muslims trying to enter. - Around 50 Israeli forces along with 18 settlers tour Al-Aqsa compound. Jan. 8: A Jewish Israeli man is stabbed and injured by an unknown assailant while walking near the Old City’s Damascus Gate. Jan. 9: Israeli police detain at least seven Palestinians in a series of raids in the Old City over the stabbing a day earlier. - Yedioth Ahronoth reports that the Israeli Intelligence (Shabak) frustrated an operation that was intended to blow the Dome of the Rock by an American immigrant. Jan. 11: Israeli police forces detain seven Palestinians from Silwan after a settler vehicle was torched in the area. Jan. 12: A Jerusalem magistrate court has ruled that Israeli settlers who occupied Palestinian homes in East Jerusalem may not make substantial changes to the properties. - Settlers tour Al-Aqsa Mosque compound. Jan. 13: Israeli forces detained three 14-year old youth during a raid on Issawiyya and two women while leaving Al-Aqsa Mosque. Jan. 14: Jewish extremists morning punctured the tires of 11 vehicles in Beit Safafa. -

November 2014 Al-Malih Shaqed Kh

Salem Zabubah Ram-Onn Rummanah The West Bank Ta'nak Ga-Taybah Um al-Fahm Jalameh / Mqeibleh G Silat 'Arabunah Settlements and the Separation Barrier al-Harithiya al-Jalameh 'Anin a-Sa'aidah Bet She'an 'Arrana G 66 Deir Ghazala Faqqu'a Kh. Suruj 6 kh. Abu 'Anqar G Um a-Rihan al-Yamun ! Dahiyat Sabah Hinnanit al-Kheir Kh. 'Abdallah Dhaher Shahak I.Z Kfar Dan Mashru' Beit Qad Barghasha al-Yunis G November 2014 al-Malih Shaqed Kh. a-Sheikh al-'Araqah Barta'ah Sa'eed Tura / Dhaher al-Jamilat Um Qabub Turah al-Malih Beit Qad a-Sharqiyah Rehan al-Gharbiyah al-Hashimiyah Turah Arab al-Hamdun Kh. al-Muntar a-Sharqiyah Jenin a-Sharqiyah Nazlat a-Tarem Jalbun Kh. al-Muntar Kh. Mas'ud a-Sheikh Jenin R.C. A'ba al-Gharbiyah Um Dar Zeid Kafr Qud 'Wadi a-Dabi Deir Abu Da'if al-Khuljan Birqin Lebanon Dhaher G G Zabdah לבנון al-'Abed Zabdah/ QeiqisU Ya'bad G Akkabah Barta'ah/ Arab a-Suweitat The Rihan Kufeirit רמת Golan n 60 הגולן Heights Hadera Qaffin Kh. Sab'ein Um a-Tut n Imreihah Ya'bad/ a-Shuhada a a G e Mevo Dotan (Ganzour) n Maoz Zvi ! Jalqamus a Baka al-Gharbiyah r Hermesh Bir al-Basha al-Mutilla r e Mevo Dotan al-Mughayir e t GNazlat 'Isa Tannin i a-Nazlah G d Baqah al-Hafira e The a-Sharqiya Baka al-Gharbiyah/ a-Sharqiyah M n a-Nazlah Araba Nazlat ‘Isa Nazlat Qabatiya הגדה Westהמערבית e al-Wusta Kh. -

BULLETIN - JANUARY, 2012 Bulletin Electric Railroaders’ Association, Incorporated Vol

The ERA BULLETIN - JANUARY, 2012 Bulletin Electric Railroaders’ Association, Incorporated Vol. 55, No. 1 January, 2012 The Bulletin WELCOME TO OUR NEW READERS Published by the Electric Railroaders’ Association, For many of you, this is the first time that ing month. This month’s issue includes re- Incorporated, PO Box you are receiving The Bulletin. It is not a ports on transit systems across the nation. In 3323, New York, New new publication, but has been produced by its 53-year history there have been just three York 10163-3323. the New York Division of the Electric Rail- Editors: Henry T. Raudenbush (1958-9), Ar- roaders’ Association since May, 1958. Over thur Lonto (1960-81) and Bernie Linder For general inquiries, the years we have expanded the scope of (1981-present). The current staff also in- contact us at bulletin@ coverage from the metropolitan New York cludes News Editor Randy Glucksman, Con- erausa.org or by phone area to the nation and the world, and mem- tributing Editor Jeffrey Erlitz, and our Produc- at (212) 986-4482 (voice ber contributions are always welcomed in this tion Manager, David Ross, who puts the mail available). ERA’s website is effort. The first issue foretold the abandon- whole publication together. We hope that you www.erausa.org. ment of the Polo Grounds Shuttle the follow- will enjoy reading The Bulletin Editorial Staff: Editor-in-Chief: Bernard Linder THIRD AVENUE’S POOR FINANCIAL CONDITION LED News Editor: Randy Glucksman TO ITS CAR REBUILDING PROGRAM 75 YEARS AGO Contributing Editor: Jeffrey Erlitz This company, which was founded in 1853, the equipment was in excellent condition and was able to survive longer than any other was well-maintained. -

Jerusalem: City of Dreams, City of Sorrows

1 JERUSALEM: CITY OF DREAMS, CITY OF SORROWS More than ever before, urban historians tell us that global cities tend to look very much alike. For U.S. students. the“ look alike” perspective makes it more difficult to empathize with and to understand cultures and societies other than their own. The admittedly superficial similarities of global cities with U.S. ones leads to misunderstandings and confusion. The multiplicity of cybercafés, high-rise buildings, bars and discothèques, international hotels, restaurants, and boutique retailers in shopping malls and multiplex cinemas gives these global cities the appearances of familiarity. The ubiquity of schools, university campuses, signs, streetlights, and urban transportation systems can only add to an outsider’s “cultural and social blindness.” Prevailing U.S. learning goals that underscore American values of individualism, self-confidence, and material comfort are, more often than not, obstacles for any quick study or understanding of world cultures and societies by visiting U.S. student and faculty.1 Therefore, international educators need to look for and find ways in which their students are able to look beyond the veneer of the modern global city through careful program planning and learning strategies that seek to affect the students in their “reading and learning” about these fertile centers of liberal learning. As the students become acquainted with the streets, neighborhoods, and urban centers of their global city, their understanding of its ways and habits is embellished and enriched by the walls, neighborhoods, institutions, and archaeological sites that might otherwise cause them their “cultural and social blindness.” Jerusalem is more than an intriguing global historical city. -

An Examination of Israeli Municipal Policy in East Jerusalem Ardi Imseis

American University International Law Review Volume 15 | Issue 5 Article 2 2000 Facts on the Ground: An Examination of Israeli Municipal Policy in East Jerusalem Ardi Imseis Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/auilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Imseis, Ardi. "Facts on the Ground: An Examination of Israeli Municipal Policy in East Jerusalem." American University International Law Review 15, no. 5 (2000): 1039-1069. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FACTS ON THE GROUND: AN EXAMINATION OF ISRAELI MUNICIPAL POLICY IN EAST JERUSALEM ARDI IMSEIS* INTRODUCTION ............................................. 1040 I. BACKGROUND ........................................... 1043 A. ISRAELI LAW, INTERNATIONAL LAW AND EAST JERUSALEM SINCE 1967 ................................. 1043 B. ISRAELI MUNICIPAL POLICY IN EAST JERUSALEM ......... 1047 II. FACTS ON THE GROUND: ISRAELI MUNICIPAL ACTIVITY IN EAST JERUSALEM ........................ 1049 A. EXPROPRIATION OF PALESTINIAN LAND .................. 1050 B. THE IMPOSITION OF JEWISH SETTLEMENTS ............... 1052 C. ZONING PALESTINIAN LANDS AS "GREEN AREAS".....