Sherlock Holmes in Khartoum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue #53 Spring 2006

T HE NORWEGIAN EXPLORERS OF MINNESOTA, INC. ©2006 Winter, 2006 EXPLORATIONS Issue #53 EXPLORATIONSEXPLORATIONS From the (Outgoing) President . Julie McKuras, ASH, BSI Inside this issue: Internet Explorations 2 Annual Meeting & Dinner 3 Explorer Travels 4 A New Take on Mrs. Hudson 5 Holmes and Plastic Man? 6 The English 8 A Toast to Mycroft 9 Sherlock’s Last Case 9 From the Editor’s Desk Study Group 10 n this last issue of Explorations for 2006 delivered at our annual dinner, joining I we recap our recent annual meeting and frequent contributors Mike Eckman and dinner, notable for a changing of the guard Bob Brusic as well as Study Group reviewer as Julie McKuras stepped down after an Charles Clifford. Phil Bergem continues his energetic nine years as president of the Nor- Internet Explorations, and we look forward wegian Explorers. We are sure that our new to an upcoming performance of a Sher- president, Gary Thaden, will ably carry on lockian play. in the tradition of Julie and all our past Letters to the editor or other submis- leaders, including our founder and Siger- sions for Explorations are always welcome. son, the late E.W. “Mac” McDiarmid. We Please email items in Word or plain text also note travels by Explorers to two recent format to [email protected] conferences, both of which featured speak- ers from the ranks of the Explorers. We John Bergquist, BSI welcome Ray Riethmeier as a contributor to Editor, Explorations the newsletter by printing his fine toast Page 2 EXPLORATIONS Issue #53 From the (Incoming) President Internet Explorations . -

To Look for a Society in Your Area

ZSOC-GEO.TXT ACTIVE SHERLOCKIAN SOCIETIES (GEOGRAPHICAL) (AS OF JULY 17, 2017): Baker Street Vienna Silvia Groniewicz AT Vienna Anton-Baumgartnerstrasse 44/C5/1/1 1230 Vienna AUSTRIA The Sydney Passengers Bill Barnes AU NS Sydney 19 Malvern Avenue Manly, N.S.W. 2095 AUSTRALIA The Sherlock Holmes Society of South Australia Mark Chellew AU SA Adelaide P.O. Box 85 Daw Park, SA 5041 AUSTRALIA The Sherlock Holmes Society of Melbourne Michael Duke AU VI Melbourne 3 Gillies Street Hampton, Vic. 3188 AUSTRALIA The Sherlock Holmes Society of Western Australia Fred Rutter AU WA Perth 49 Cedar Way Forrestfield, WA 6058 AUSTRALIA Le peloton des cyclistes solitaires Cedric C. Goffinet BE Brussels Rue de Levallois-Perret 46 B-1080 Bruxelles The 221Bees Ivo Dekoning BE Lummen Goeslaerstraat 45 3560 Lummen BELGIUM The Isadora Klein Amateur Mendicant Society Carlos Orsi Martinho BR Jundiai r. Zacarias de Goes, 404, ap. 92 Jundiai-SP 13201-800 BRAZIL The Singular Society of the Baker Street Dozen Charles Prepolec Page 1 ZSOC-GEO.TXT CA AB Calgary 101 Royal Bay NW Calgary, AB T3G 5J6 CANADA The Wisteria Lodgers of Edmonton Constantine Kaoukakis CA AB Edmondon 9705 163rd Street NW Edmonton, AB T5P 3N1 CANADA The Stormy Petrels of British Columbia Krista Lee Munro CA BC Vancouver e-mail: [email protected] CANADA The Great Herd of Bisons of the Fertile Plains Ihor Mayba CA MB Winnipeg 6 Melness Bay Winnipeg, MB R2K 2T5 CANADA The Halifax Spence Munros Mark J. Alberstat CA NS Halifax 46 Kingston Crescent Dartmouth, NS B3A 2M2 CANADA The Main Street Irregulars Trevor S. -

2015 Jhws Treasure Hunt

2015 JHWS TREASURE HUNT “Mr. Sherlock Holmes” Category: Holmes’s personality 1. This author, while writing his own stories about a fatherly detective, went so far as to assert that Sherlock Holmes was not a man, but a god. Who? (1 pt.) Answer: G.K. Chesterton, author of the Father Brown mysteries ---See The Sherlock Holmes Collection, The University of Minnesota, USH Volume I, Section VI: The Writings About the Writings, Chesterson, G.K., Sherlock Holmes the God, G.K.’s Weekly (February 21, 1935), at lib.umn.edu, and numerous others. ---Full quote: “Not once is there a glance at the human and hasty way in which the stories were written; not once even an admission that they were written. The real inference is that Sherlock Holmes really existed and that Conan Doyle never existed. If posterity only reads these latter books, it will certainly suppose them to be serious. It will imagine that Sherlock Holmes was a man. But he was not; he was only a god.” 2. Holmes did not, perhaps, have a knowledge of women across the continents, but, according to Watson, Holmes did hold a position across several of them. How many continents and what position? (2 pts.) Answer: Three, position of unofficial adviser and helper to everybody who is absolutely puzzled ---W., p. 191, IDEN: I smiled and shook my head. "I can quite understand you thinking so," I said. "Of course, in your position of unofficial adviser and helper to everybody who is absolutely puzzled, throughout three continents, you are brought in contact with all that is strange and bizarre. -

Writer's Guide to the World of Mary Russell

Information for the Writer of Mary Russell Fan Fiction Or What Every Writer needs to know about the world of Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes as written by Laurie R. King in what is known as The Kanon By: Alice “…the girl with the strawberry curls” **Spoiler Alert: This document covers all nine of the Russell books currently in print, and discloses information from the latest memoir, “The Language of Bees.” The Kanon BEEK – The Beekeeper’s Apprentice MREG – A Monstrous Regiment of Women LETT – A Letter of Mary MOOR – The Moor OJER – O Jerusalem JUST – Justice Hall GAME – The Game LOCK – Locked Rooms LANG – The Language of Bees GOTH – The God of the Hive Please note any references to the stories about Sherlock Holmes published by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (known as The Canon) will be in italics. The Time-line of the Books BEEK – Early April 1915 to August of 1919 when Holmes invites the recovering Russell to accompany him to France and Italy for six weeks, to return before the beginning of the Michaelmas Term in Oxford (late Sept.) MREG – December 26, 1920 to February 6, 1921 although the postscript takes us six to eight weeks later, and then several months after that with two conversations. LETT – August 14, 1923 to September 8, 1923 MOOR – No specific dates given but soon after LETT ends, so sometime the end of September or early October 1923 to early November 1923. We know that Russell and Holmes arrived back at the cottage on Nov. 5, 1923. OJER – From the final week of December 1918 until approx. -

Sherlock Holmes

SHERLOCK HOLMES THE CARD GAME For three or more players, 8 years of age and upwards INTRODUCTION In principle, the play of the cards puts players in the place of Holmes and Watson as they would set out to solve one of their celebrated cases one hundred years ago. The game starts at 221B Baker Street, with Holmes waking Watson from sleep – The game is afoot! Like them, players travel about by Hansom or by Train, visiting locations in the Country or in London, Scotland Yard, or back to Baker Street. Clues will be found; Suspects will be named, Telegrams received, Disguises used. Police Inspectors will interfere, Arrests be made, and Alibis provided. Thick Fog will confuse everyone! Finally, one player will be identified as the Villain, and captured – or – alternatively, successfully escape the clutches of his pursuers! HOW TO PLAY Take The Game is Afoot! card, and put it to one side, face down. Take the four Villain cards, shuffle, and place one of them with The Game is Afoot! card, again face down. Leave the other three Villain cards to one side for the moment. Shuffle the remainder of the pack and then count out enough cards face down to provide 6 cards for each player (including The Game is Afoot! and Villain cards which have been put to one side). Thus for 3 players, count out 16 cards, for 4 players count out 22 cards, etc. To these add The Game is Afoot! and Villain cards, re-shuffle thoroughly and deal six cards to each player. Add the remaining three Villain cards to the rest of the pack, re-shuffle, and place face down to form a draw pile. -

The Final Tales of Sherlock Holmes - Volume 1 - the Musical Murders: Volume One Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE FINAL TALES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES - VOLUME 1 - THE MUSICAL MURDERS: VOLUME ONE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK John A. Little | 156 pages | 31 Mar 2014 | MX Publishing | 9781780925653 | English | London, United Kingdom The Final Tales of Sherlock Holmes - Volume 1 - The Musical Murders: Volume one PDF Book Story was very. Book 1. Please try again. Unfollow podcast failed. Adding to library failed. Book Holmes and Watson, now ages 71 and 70, are together again. In this compelling short story, Holmes and Watson receive an early internment as punishment for infiltrating the Body-Snatchers Club. Paperback , pages. There is a coded message left for Holmes with a line of scripture from the Book of Jude in the Bible, specifically Jude The Final Tales of Sherlock Holmes 1. Please try again later. Further details I leave to the reader to discover. Cancel anytime. It is then revealed that Mycroft was gay. And what have the Bloomsbury Group and the Diogenes Club got to do with anything? Follow podcast failed. Quoth the Raven… Taxes where applicable. He meets up with his colleague and friend, Dr. Dec 09, Steve rated it it was amazing. Reviews - Please select the tabs below to change the source of reviews. Holmes and Watson are plunged into the secret underworld of London, where a serial killer of musical gay men is afoot. Lists with This Book. No trivia or quizzes yet. Thanks to Royal Jelly, Holmes is a fit year-old who has lost his interest in bees and returned to detecting, joining forces again with his colleague and friend, Dr. -

The Greek Interpreter

The Greek Interpreter Arthur Conan Doyle This text is provided to you “as-is” without any warranty. No warranties of any kind, expressed or implied, are made to you as to the text or any medium it may be on, including but not limited to warranties of merchantablity or fitness for a particular purpose. This text was formatted from various free ASCII and HTML variants. See http://sherlock-holm.esfor an electronic form of this text and additional information about it. This text comes from the collection’s version 3.1. uring my long and intimate acquain- better powers of observation than I, you may take tance with Mr. Sherlock Holmes I had it that I am speaking the exact and literal truth.” never heard him refer to his relations, and D “Is he your junior?” hardly ever to his own early life. This ret- “Seven years my senior.” icence upon his part had increased the somewhat inhuman effect which he produced upon me, until “How comes it that he is unknown?” sometimes I found myself regarding him as an iso- “Oh, he is very well known in his own circle.” lated phenomenon, a brain without a heart, as defi- “Where, then?” cient in human sympathy as he was pre-eminent in “Well, in the Diogenes Club, for example.” intelligence. His aversion to women and his disin- I had never heard of the institution, and my clination to form new friendships were both typical face must have proclaimed as much, for Sherlock of his unemotional character, but not more so than Holmes pulled out his watch. -

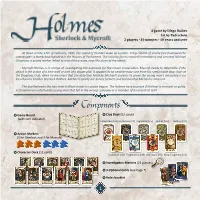

Holmes: Sherlock & Mycroft Rulebook

A game by Diego Ibáñez Art by Pedro Soto 2 players · 30 minutes · 10 years and over At dawn on the 24th of February, 1895, the sound of thunder woke up London. A big column of smoke foreshadowed the catastrophe: a bomb had exploded in the Houses of Parliament. The security forces reacted immediately and arrested Michael Chapman, a young worker linked to anarchist groups, near the place of the attack. Mycroft Holmes is in charge of investigating the explosion for the Crown prosecution. Mycroft needs to determine if the attack is the action of a lone wolf or part of a bigger plot. It appears to be another easy case from his comfortable easy chair at the Diogenes Club, when he discovers that the detective hired by Michael’s parents to prove the young man’s innocence is no less than his brother Sherlock Holmes. Michael’s family are Surrey farmers and believe that Michael is innocent. The duel between the two most brilliant minds in London begins. The Holmes have to prove if Michael is innocent or guilty. Is Chapman an unfortunate young man that fell in the wrong company or a member of an anarchist cell? Components Game Board Clue Deck (52 cards) (with turn indicator) False Pass (×3) Explosive (×4) Cigarette (×5) Bullet (×6) Button (×7) Action Markers (3 for Sherlock and 3 for Mycroft) Character Deck (12 cards) Footprint (×8) Fingerprint (×9) Wildcard (×5) Map Fragment (×5) Investigation Markers (24 glasses) 3 Optional Cards(see Page 7) Rules booklet 1 Preparation of the Game 1 The game board is placed on one side between the players. -

BSDB Price List (Winter 2010)

THE BATTERED SILICON DISPATCH BOXTM George A. Vanderburgh, Publisher (1–:04Jul12) E-mail: [email protected] * Website: www.batteredbox.com * Blog: www.batteredbox.wordpress.com P. O. Box 50, R.R. #4 All prices in Canadian Funds * 5% G.S.T. (#87901-5303) on all Canadian Orders P. O. Box 122 Eugenia, Ontario Postage $10.00 for 1st volume to maximum of $25.00 – Overseas shipping at cost Sauk City, Wisconsin CANADA N0C 1E0 Can$ – US$ – € cheques – Paypal accepted with fee, no credit card orders please U.S.A. 53583-0122 SHERLOCKIAN SCHOLARSHIP (Conventional) ___ THE BASIC 100 (Shaw/Thiel/Cagnat) Chapbook, 56p. ISBN 1-896648-54-1 @ $12.50.. ______ ___ BAKER STREET BRIEFS (Bigelow) Plastic Comb, 178p. ISBN 0-88773-40-X @ $20.00. ______ ___ BAKER STREET BRIEFS (Bigelow) Casebound, 178p. ISBN 0-88773-045-0 @ $35.00. ______ ___ THE GAME IS AFOOT! (Layng) Hard Cover, 199p. ISBN 1-896032-68-0 @ $30.00. ______ ___ FROM BALTIMORE TO BAKER STREET (Hyder) Hard Cover, 216p. ISBN 1-896032-35-4 @ $30.00. ______ ___ SHERLOCK IN BLACK (Brogdon) Chapbook, 29p. ISBN 1-896032-45-1 @ $10.00. ______ ___ FIVE SHERLOCKIAN WALKS IN LONDON (Dorn/Cagnat) Chapbook, 48p. @ $10.00. ______ ___ THE PARLOUR GAMES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES (Dorn/Cagnat) Chapbook, 65p. ISBN 1-896648-67-3 @ $10.00.. ______ ___ BIBLIOMANIA (Austin) Chapbook, 50p. ISBN 1-896648-74-6 @ $10.00. ______ ___ THE LOG OF “THE GLORIA SCOTT” (Brodie/Randall) Hard Cover, 278p. ISBN 1-55246-057-6 @ $45.00. ______ ___ WHO WAS BRUCE-PARTINGTON? (Kean) Chapbook, 36p. -

BSDB Price List (Winter 2010)

THE BATTERED SILICON DISPATCH BOXTM George A. Vanderburgh, Publisher (1–:22Feb16) E-mail: [email protected] * Website: www.batteredbox.com * Blog: www.batteredbox.wordpress.com P. O. Box 50, R.R. #4 * 5% G.S.T. (#87901-5303) on all Canadian Orders · – Overseas shipping at cost P. O. Box 122 Eugenia, Ontario All prices in US Funds · Postage $15.00 for 1st volume to maximum of $35.00 Sauk City, Wisconsin CANADA N0C 1E0 Can$ – US$ – € cheques – PayPal accepted with modest fee, no credit card orders please U.S.A. 53583-0122 SHERLOCKIAN SCHOLARSHIP (Conventional) ___ THE BASIC 100 (Shaw/Thiel/Cagnat) Chapbook, 56p. ISBN 1-896648-54-1 @ $12.50.. ______ ___ BAKER STREET BRIEFS (Bigelow) Plastic Comb, 178p. ISBN 0-88773-40-X @ $20.00. ______ ___ BAKER STREET BRIEFS (Bigelow) Casebound, 178p. ISBN 0-88773-045-0 @ $35.00. ______ ___ THE GAME IS AFOOT! (Layng) Hard Cover, 199p. ISBN 1-896032-68-0 @ $30.00. ______ ___ FROM BALTIMORE TO BAKER STREET (Hyder) Hard Cover, 216p. ISBN 1-896032-35-4 @ $30.00. ______ ___ SHERLOCK IN BLACK (Brogdon) Chapbook, 29p. ISBN 1-896032-45-1 @ $10.00. ______ ___ FIVE SHERLOCKIAN WALKS IN LONDON (Dorn/Cagnat) Chapbook, 48p. @ $10.00. ______ ___ THE PARLOUR GAMES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES (Dorn/Cagnat) Chapbook, 65p. ISBN 1-896648-67-3 @ $10.00.. ______ ___ BIBLIOMANIA (Austin) Chapbook, 50p. ISBN 1-896648-74-6 @ $10.00. ______ ___ THE LOG OF “THE GLORIA SCOTT” (Brodie/Randall) Hard Cover, 278p. ISBN 1-55246-057-6 @ $45.00. ______ ___ WHO WAS BRUCE-PARTINGTON? (Kean) Chapbook, 36p. -

5 Must-Read Mysteries for Summer 2019

Jul 9, 2019, 11:19pm 5 Must-Read Mysteries For Summer 2019 Micah Solomon Contributor Entrepreneurs Customer service consultant, keynote speaker. [email protected] There’s nothing like a well-plotted mystery to read on a summer’s day–or, if you dare, a summer’s night. Here are five first-rate mysteries, fresh off the presses, that I’m eager to recommend. Finding Mrs. Ford, by Deborah Goodrich Royce (Book Cover Image) Finding Mrs. Ford, by Deborah Goodrich Royce If you’ve had the chance to summer by the seaside in Watch Hill, Rhode Island, a popular locale for those in the money and in the know, you’d peg the town as an unlikely place for a mystery to unfold. (Watch Hill is also home to an iconic Forbes Five Star Victorian hotel, Ocean House, of which author Royce is co-owner.) This is part of the magic when Royce draws you into her plot via her dazzling treatment of this setting, and other equally well-drawn locales, including disco-era suburban Detroit, which figures heavily in the plot as well. The novel, which is Royce’s first, features equally three-dimensional characters and plot twists that are engaging and original as well. Once you’ve enjoyed Finding Mrs. Ford, you’ll find yourself expecting more great things upcoming from this author, as am I. The Paragon Hotel, by Lyndsay Faye (Book Cover Image) The Paragon Hotel, by Lyndsay Faye Equal parts historical fiction and crime drama, The Paragon Hotel is set in Portland, Oregon (not the Birkenstocks-and-sandals version of Portland in 2019, but the 1921 Jim Crow version that most Pacific Northwesterners are ignorant of or would rather forget). -

Sherlockiana, Travel Writing and the Co-Production of the Sherlock Holmes Stories

Mobile Holmes: Sherlockiana, travel writing and the co-production of the Sherlock Holmes stories David McLaughlin Department of Geography University of Cambridge This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Emmanuel College May 2017 Mobile Holmes: Sherlockiana, Travel Writing and the Co-Production of the Sherlock Holmes Stories David McLaughlin Abstract This thesis is a study of the ways in which readers actively and collaboratively co-produce fiction. It focuses on American Sherlockians, a group of devotees of Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories. At its centre is an analysis of geographical and travel writings these readers produced about Holmes’s life and world, in the later years of the twentieth century. I argue that Sherlockian writings indicate a tendency to practise what I term ‘expansionary literary geography’; that is, a species of encounter with fiction in which readers harness literature’s creative agency in order to consciously add to or expand the literary spaces of the text. My thesis is a work of literary geography. I am indebted to recent work that theorises reading as a dynamic practice which occurs in time and space. My work develops this theoretical lens by considering the fictional event in the light of encounters which are collaborative, collective and ongoing. I present my findings across four substantive chapters, each of which elucidates a different aspect of Sherlockians’ expansionary literary geography: first, mapping, where Sherlockians who set out to definitively map the world as Doyle wrote it keep re-drawing its boundaries outside of his texts; secondly, creative writing, by which readers make Holmes move while ensuring he never wanders too far from the canon; thirdly, debate, a popular pastime among American Sherlockians and a means for readers to build Holmes’s world out of their own memories and experiences; and fourthly, literary tourism, used by three exemplary readers as a means of walking Holmes into the world.